Chinese animation

Chinese animation refers to animation made in China. In Chinese, donghua (simplified Chinese: 动画; traditional Chinese: 動畫; pinyin: dònghuà) describes all animated works, regardless of style or origin. However, outside of China and in English, donghua is colloquial for Chinese animation and refers specifically to animation produced in China.

History

The history of animated moving pictures in China began in 1918 when an animation piece from the United States titled Out of the Inkwell landed in Shanghai. Cartoon clips were first used in advertisements for domestic products. Though the animation industry did not begin until the arrival of the Wan brothers in 1926. The Wan brothers produced the first Chinese animated film with sound, The Camel's Dance, in 1935. The first animated film of notable length was Princess Iron Fan in 1941. Princess Iron Fan was the first animated feature film in Asia and it had great impact on wartime Japanese Momotarō animated feature films and later on Osamu Tezuka.[1] China was relatively on pace with the rest of the world up to the mid-1960s, with the Wan's brothers Havoc in Heaven earning numerous international awards.

China's golden age of animation would come to an end following the onset of the Cultural Revolution in 1966.[2] Many animators were forced to quit. If not for harsh economic conditions, the mistreatment of the Red Guards would threaten their work. The surviving animations would lean closer to propaganda. By the 1980s, Japan would emerge as the animation powerhouse of Eastern Asia, leaving China's industry far behind in reputation and productivity. Though two major changes would occur in the 1990s, igniting some of the biggest changes since the exploration periods. The first is a political change. The implementation of a socialist market economy would push out traditional planned economy systems.[3] No longer would a single entity limit the industry's output and income. The second is a technological change with the arrival of the Internet. New opportunities would emerge from Flash animations and the contents became more open. Today China is drastically reinventing itself in the animation industry with greater influences from Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Terminology

Chinese animations today can best be described in two categories. The first type are "conventional animations" produced by corporations of well-financed entities. These content falls along the lines of traditional 2D cartoons or modern 3D CG animated films distributed via cinemas, DVD or broadcast on TV. This format can be summarized as a reviving industry coming together with advanced computer technology and low cost labor.[4]

The second type are "webtoons" produced by corporations or sometimes just individuals. These contents are generally flash animations ranging anywhere from amateurish to high quality, hosted publicly on various websites. While the global community has always gauged industry success by box office sales. This format cannot be denied when measured in hits among a population of 1.3 billion in just mainland China alone. Most importantly it provides greater freedom of expression on top of potential advertising.

Characteristics

In the 1920s, the pioneering Wan brothers believed that animations should emphasize on a development style that was uniquely Chinese. This rigid philosophy stayed with the industry for decades. Animations were essentially an extension of other facets of Chinese arts and culture, drawing more contents from ancient folklores and manhua. There is a close relationship between Chinese literature works and classic Chinese animation. A significant number of classical Chinese animation films were inspired and prototyped by ancient Chinese literature.[5] An example of a traditional Chinese animation character would be Monkey King, a character transitioned from the classic literature Journey to the West to the 1964 animation Havoc in Heaven. Also drawing on tradition was the ink-wash animation developed by animators Te Wei and Qian Jiajun in the 1960s. Based on Chinese ink-wash painting, several films were produced in this style, starting with Where is Mama (1960).[6] However, the technique was time-consuming and was gradually abandoned by animation studios.[7]

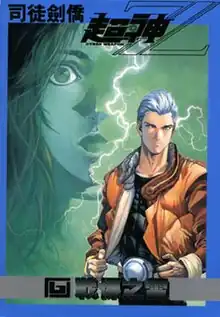

The concept of Chinese animations have begun loosening up in recent years without locking into any particular one style. One of the first revolutionary change was in the 1995 manhua animation adaptation Cyber Weapon Z. The style consist of characters that are practically indistinguishable from any typical anime, yet it is categorized as Chinese animation. It can be said that productions are not necessarily limited to any one technique; that water ink, puppetry, computer CG are all demonstrated in the art.

Newer waves of animations since the 1990s, especially flash animations, are trying to break away from the tradition. In 2001 Time Asia would rate the Taiwanese webtoon character A-kuei as one of the top 100 new figures in Asia.[8] The appearance of A-kuei with the large head, would probably lean much closer to children's material like Doraemon. So changes like this signify a welcoming transition, since folklore-like characters have always had a hard time gaining international appeal. GoGo Top magazine, the first weekly Chinese animation magazine, conducted a survey and proved that only 1 out of 20 favorite characters among children was actually created domestically in China.[9]

In 1998, Wang Xiaodi directed the full-length animated feature Grandma and Her Ghosts.

Conventional animation market

The demographics of the Chinese consumer market show an audience where 11% are under the age of 13, 59% between 14 and 17, and 30% over 18 years of age. Potentially 500 million people could be identified as cartoon consumers.[10] China has 370 million children, one of the world's largest animation audiences.[11]

From the financial perspective, Quatech Market Research surveyed ages between 14 and 30 in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou and found that over 1.3 billion RMB (about US$163 million) was spent on cartoons every year, but more than 80% of the revenue flows straight out of the country. Further studies show that 60% still prefer Japanese anime, 29% prefer Americans, and just 11 percent favor those made by Chinese mainland, Taiwan or Hong Kong animators.

From 2006 to present, the Chinese government has considered animation as a key sector for the birth of a new national identity and for the cultural development in China. The government has started to promote the development of cinema and TV series with the aim of reaching 1% of GDP in the next five years against an investment of around RMB250-350 million (€29-41 million). It supported the birth of about 6000 animation studios and 1300 universities which provide animation studies. In 2010, 220,000 minutes of animations were produced, making China the world's biggest producer of cartoons on TV.[12]

In 1999 Shanghai Animation Film Studio spent 21 million RMB (about US$2.6 million) producing the animation Lotus Lantern. The film earned a box office income of more than RMB 20 million (about US$2.5 million), but failed to capitalize on any related products. The same company shot a cartoon series Music Up in 2001, and although 66% of its profits came from selling related merchandise, it lagged far behind foreign animations.[9]

The year 2007 saw the debut of the popular Chinese Series, The Legend of Qin. It boasted impressive 3d graphics and an immersive storyline. Its third season was released on 23 June 2010. Its fourth season is under production.

One of the most popular manhua in Hong Kong was Old Master Q. The characters were converted into cartoon forms as early as 1981, followed by numerous animation adaptations including a widescreen DVD release in 2003. While the publications remained legendary for decades, the animations have always been considered more of a fan tribute. And this is another sign that newer generations are further disconnected with older styled characters. Newer animations like My Life as McDull has also been introduced to expand on the modern trend.

In 2005 the first 3D CG-animated movie from Shenzhen China, Thru the Moebius Strip was debuted. Running for 80 minutes, it is the first 3D movie fully rendered in mainland China to premiere in the Cannes Film Festival.[13] It was a critical first step for the industry. The immensely popular kids's animated series Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf came out the same year.

In November 2006 an animation summit forum was held to announce China's top 10 most popular domestic cartoons as Century Sonny, Tortoise Hanba's Stories, Black Cat Detective, SkyEye, Lao Mountain Taoist, Nezha Conquers the Dragon King, Wanderings of Sanmao, Zhang Ga the Soldier Boy, The Blue Mouse and the Big-Faced Cat and 3000 Whys of Blue Cat.[14] Century Sonny is a 3D CG-animated TV series with 104 episodes fully rendered.

In 2011 Vasoon Animation released Kuiba. The film tells the story of how a boy attempts to save a fantasy world from an evil monster who, unknowingly, is inside of him. The film borrows from a Japanese "hot-blooded" style, refreshing the audience's views on Chinese animation. Kuiba was critically acclaimed, however it commercially fell below expectations.[15] It was reported that the CEO Wu Hanqing received minority help from a venture capital fund at Tsinghua University to complete "Kuiba."[16] This film also holds the distinction of being the first big Chinese animation series to enter the Japanese market.[17] From July 2012 to July 2013, YouYaoQi released One hundred thousand bad jokes.

In 2015, Monkey king: Hero is back gain 2.85 million USD box office, it was the highest-grossing animated film in China.[18]

The most important award for Chinese animation is the Golden Monkey Award.[19]

Flash animation market

On 15 September 1999 FlashEmpire became the first flash community in China to come online. While it began with amateurish contents, it was one of the first time any form of user-generated contents was offered in the mainland. By the beginning of 2000, it averaged 10,000 hits daily with more than 5,000 individual work published. Today it has more than 1 million members.[20]

In 2001, Xiao Xiao, a series of flash animations about kung fu stick figures became an Internet phenomenon totaling more than 50 million hits, most of which in mainland China. It also became popular overseas with numerous international artists borrowing the Xiao Xiao character for their own flash work in sites like Newgrounds.

On 24 April 2006 Flashlands.com was launched, hosting a variety of high quality flash animations from mainland China. The site is designed to be one of the first cross-cultural site allowing English speakers easy access to domestic productions. Though the success of the site has yet to be determined.

In October 2006, 3G.NET.CN paid 3 million RMB (about US$380,000) to produce A Chinese odyssey, the flash version of Stephen Chow's A Chinese Odyssey in flash format.[21]

Government's role in the industry

For every quarter, the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television announces the Outstanding Domestic Animated Television Productions, which is given to the works that "persist with correct value guidance" (坚持正确价值导向) and "possess relatively high artistic quality and production standards" (具有较高艺术水准和制作水平), and recommends the television broadcasters in Mainland China to give priority when broadcasting such series.[22]

Criticism

Statistics from China's State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) indicate domestic cartoons aired 1hr 30 minutes each day from 1993 to 2002, and that by the end of 2004, it increased the airing time of domestic cartoons to 2hrs per day.[23] The division requested a total of 2,000 provinces to devote a show time of 60,000 minutes to domestically-produced animations and comic works. But statistics show that domestic animators can only provide enough work for 20,000 minutes, leaving a gap of 40,000 minutes that can only be filled by foreign programs. Though insiders are allegedly criticizing domestic cartoons for its emphasis on education over entertainment.[11]

SARFT also have a history of taking protectionism actions such as banning foreign programming, such as the film Babe: Pig in the City. While statistics are proving there are not enough domestic materials available, the administration continues to ban foreign materials. On 15 February 2006 another notice is issued to ban cartoons that incorporated live actors. As reported by Xinhua News Agency, the commission did not want CGI and 2D characters alongside human actors. Doing so would jeopardize the broadcast order of homemade animation and mislead their development. Neither ban makes logical sense to the general public, according to foreign sources.[24][25]

Literature and scholarship

There is little discussion of Chinese animation in English. Daisy Yan Du's PhD dissertation, On the Move: The Trans/national Animated Film in 1940s–1970s China (University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2012), is by far the most systematic analysis of early Chinese animation before 1980.[26] Weihua Wu's PhD dissertation, Animation in Postsocialist China: Visual Narrative, Modernity, and Digital Culture (City University of Hong Kong, 2006), discusses contemporary Chinese animation in the digital age after 1980.[27] Besides the two major works, there are other articles and book chapters written by John Lent, Paola Voci, Mary Farquhar, and others about Chinese animation. The first English-language monograph devoted to Chinese animation was Rolf Giesen's Chinese Animation: A History and Filmography, 1922–2012 (McFarland & Company, Jefferson NC, 2015).

See also

References

- Du, Daisy Yan (May 2012). "A Wartime Romance: Princess iron Fan and the Chinese Connection in Early Japanese Animation". On the Move: The Trans/national Animated Film in 1940s–1970s China (Ph.D.). The University of Wisconsin-Madison. pp. 15–60.

- Qing Yun. "Qing Yun" (Archived 21 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine). Qing Yun.com. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- Socialist Marketing Economy. "Socialist Marketing Economy." "Socialist Marketing Economy." Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- French, Howard W. (1 December 2004). "China Hurries to Animate Its Film Industry". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Chen, Yuanyuan (4 May 2017). "Old or new art? Rethinking classical Chinese animation". Journal of Chinese Cinemas. 11 (2): 175–188. doi:10.1080/17508061.2017.1322786. ISSN 1750-8061. S2CID 54882711.

- Wang, Nan (4 June 2008). "Water-and-Ink animation". China Daily. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Fang, Liu (20 March 2012). "Is there a future for water-ink animation?". CNTV. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Huang, Joyce (28 April 2003). "A-Kuei: The animated boy who keeps us young at heart". Time. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- China Today. "China Today." "Chinese Animation Market: Monkey King vs Mickey Mouse." Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- Homepage of author Jonathan Clement. "Homepage of author Jonathan Clement Archived 6 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. "Chinese Animation." Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- People's Daily Online. ""China Opens Cartoon Industry to Private Investors". People's Daily Online. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- De Masi, Vincenzo (2013). "Discovering Miss Puff: a new method of communication in China" (PDF). KOME: An International Journal of Pure Communication Inquiry. Hungarian Communication Studies Association. 1 (2): 44, 46. ISSN 2063-7330. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- Broadcast Buyers Guide. "Broadcast Buyers Guide Archived 26 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine." "GDC Technology and Arts Alliance Media Partner for a Digital Screening Premiere at Cannes." Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- China's CityLife. "China's City Life." "Top 10 Domestic Cartoons." Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- "Chinese Animation at a Crossroads". CNTV English. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Kemp, Stuart (24 June 2011). "Beijing Calls the Toons". The Independent. London. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- "China Animation To Be Screened in Japan Before Its Mainland Theater Release". China Screen News. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Jiang, Fei; Huang, Kuo (2017). "Hero is Back- The rising of Chinese audiences: The demonstration of SHI in popularizing a Chinese animation". Global Media and China. 2 (2): 122–137. doi:10.1177/2059436417730893. ISSN 2059-4364. S2CID 194577213.

- China Daily (13 January 2017). "Animated 3-D film 'Bicycle Boy' to hit screens on 13 Jan". english.entgroup.cn. EntGroup Inc. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- FlashEmpire. "FlashEmpire Archived 22 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine. " "FlashEmpire info." Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- Embedded Flash Advertising. "Virtual China Org." "Embedded Flash Advertising." Retrieved 21 December 2006. Archived 18 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- 国家新闻出版广电总局关于推荐2016年第三季度优秀国产电视动画片的通知 (in Chinese). State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- People's Daily Online. "People's Daily Online." "Cartoon Festival Launches Monkey King Award." Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- USA Today. "Usatoday." "Animation Ban." Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- BackStageCasting. "BackStageCasting Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine." "China bans TV toons that include live actors." Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- Du, Daisy Yan (May 2012). On the Move: The Trans/national Animated Film in the 1940s–1970s China (Ph.D.). The University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Wu, Weihua (2006). Animation in Postsocialist China: Visual Narrative, Modernity, and Digital Culture. City University of Hong Kong.

External links

- China's Cartoon Industry Forum

- Remembering Te Wei at AnimationInsider.net