Chinese Roulette

Chinese Roulette (German: Chinesisches Roulette) is a 1976 West German film written and directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder. It stars Margit Carstensen, Ulli Lommel, and Anna Karina.[2] The film, a bleak psychological drama, climaxes with a truth-guessing game, which gives the film its title. The plot follows a bourgeois married couple whose infidelities are exposed by their disabled child.

| Chinese Roulette | |

|---|---|

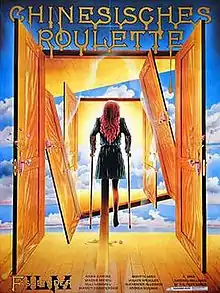

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Rainer Werner Fassbinder |

| Written by | Rainer Werner Fassbinder |

| Produced by | Michael Fengler Barbet Schroeder |

| Starring | Margit Carstensen Ulli Lommel Anna Karina Macha Méril Alexander Allerson |

| Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus |

| Edited by | Ila von Hasperg |

| Music by | Peer Raben |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 86 minutes |

| Country | West Germany |

| Language | German |

| Budget | DEM 1.1m (estimated)[1] |

Plot

Ariane and Gerhard Christ, a wealthy Munich couple, are packing before going off for the weekend, which each intends to spend abroad. While they are away their twelve-year-old daughter Angela, who is disabled and walks with crutches, has to remain home under the care of her mute governess, Traunitz. Actually, the couple have lied about their travel intentions. Convinced that his wife and daughter will be elsewhere, Gerhard takes his longtime mistress Irene Cartis — a French hairdresser — on a weekend tryst to the family's country house.

The Christ family's rural estate is run by a sinister housekeeper named Kast and her sexually ambiguous son, Gabriel. While Kast, a cruel and cranky old woman, is irritated by the visit of her employers, her son Gabriel, a pretentious aspiring writer, is hoping to exploit Gerhard's connections to get his work published. Upon entering the house with his lover Irene, Gerhard runs to the living room only to find Ariane on the floor with her lover Kolbe, Gerhard's assistant. The two couples try to overcome the uncomfortable situation and are able to laugh about the absurdity of it. They all have dinner together and, over coffee, Gabriel is allowed to read from the philosophical book he has written. He is interrupted by the arrival of Angela — who secretly planned this encounter out of hate for her parents' lack of affection — along with Traunitz and a small army of grotesque dolls. Ariane is furious with the antics of her daughter and tries to hit her, but Gerhard does not allow it. Angela is defiant; for their part, the two adulterous couples decide to continue as planned.

Angela tells Gabriel that her parents' infidelities started in response to her disability. Eleven years previously, Angela's illness appeared and her father started his relationship with his mistress. When the doctors declared Angela's condition as hopeless, her mother began an affair with Kolbe. She declares that "In their hearts, they blame me for their messed-up lives." However, Kast dismisses the child's allegation as nonsense. The next morning, Angela goes from room to room to say good morning to her parents, and finds them naked with their respective lovers. During the day, as the adulterous Christs come to terms with their respective infidelities, Angela tries to play them and their lovers off each other.

The stage is set for a night of suspenseful revelation when Angela suggests playing Chinese Roulette, a psychological guessing game, over dinner. In Chinese Roulette, one team tries to guess which one of them the other team is thinking of by asking questions. Angela selects the members of each team. On one side are Gerhardt, Angela, Gabriel and Traunitz; on the other are Ariane, Kast, Irene and Kolbe. Ariane's team asks the questions and Angela's team gives the answers. The game has an edge of cruelty, and the results involve everyone in the chateau.

The deadliest and final question posed is, "What would this person have been in the Third Reich?" Angela's response is that she would have been the commandant of a concentration camp. Kast suggests that the subject of the questions is herself, and the others uncertainly agree with her. Angela contradicts this; the subject is in fact her own mother, Ariane. Enraged by this and by Angela's hysterical laughter, Ariane points her husband's pistol at Angela, then turns and shoots Traunitz. However, this turns out to be only a superficial flesh wound. Irritated by Gabriel, Angela tells him that for the last two years she has known that he has plagiarized every word he has written.

The film ends in mystery as a second shot is heard in the darkened house, but the identity of the shooter and the victim is left to the viewer's imagination.

Cast

- Anna Karina as Irene Cartis

- Margit Carstensen as Ariane Christ

- Brigitte Mira as Kast

- Ulli Lommel as Kolbe

- Alexander Allerson as Gerhard Christ

- Volker Spengler as Gabriel Kast

- Andrea Schober as Angela Christ

- Macha Méril as Traunitz

Production

Chinese Roulette was Fassbinder's first international co-production, and his most expensive film up to that point.[1] It was produced by Michael Fengler's Albatros Production, Les Films du Losange and Tango Films.[1] It was shot during seven weeks between April and June 1976.[1] The location for the country house where the story takes place was actually a small castle at Stöckach in Unterfranken that belonged to Fassbinder's cinematographer, Michael Ballhaus.[1]

The cast is centred around actors from Fassbinder's regular troupe: Margit Carstensen, Brigitte Mira, Volker Spengler and Ulli Lommel.[1] Because it was a French co-production Fassbinder used two French stars: Anna Karina and Macha Méril, both of whom had earlier appeared in the films of Jean-Luc Godard. Fassbinder added another German actor, Alexander Allerson.[1] The bitter disabled daughter is played by Andrea Schober, whom Fassbinder cast earlier in The Merchant of Four Seasons (1972), again as the witness of her parents' infidelities.[3]

Reception

A sophisticated and stylish cinematic physiological game, Chinese Roulette was coldly received in West Germany.[4] Criticism centered on the cold intellectualism of the film.[4] American critic Andrew Sarris devoted an entire university course to the analysis of Chinese Roulette.[5]

References

- Watson, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, p. 168

- Canby, Vincent (2010). "NY Times.com: Chinese Roulette". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- Braad Thomsen, Fassbinder, p. 217

- Watson, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, p. 171

- Katz, Love is colder than Death, p. 113

Bibliography

- Braad Thomsen, Christian, Fassbinder: Life and Work of a Provocative Genius, University of Minnesota Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8166-4364-4

- Katz, Robert, Love is colder than Death: The Life and Time of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Random House, 1987, ASIN: B000OP6C1M

- Watson, Wallace Steadman, Rainer Werner Fassbinder: Film as Private and Public Art, University of South Carolina Press, 1996, ISBN 1-57003-079-0