Chinese playing cards

Playing cards (simplified Chinese: 纸牌; traditional Chinese: 紙牌; pinyin: zhǐpái) were most likely invented in China during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). They were certainly in existence by the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271-1368).[1][2][3] Chinese use the word pái (牌), meaning "plaque", to refer to both playing cards and tiles.[4] Many early sources are ambiguous, and do not specifically refer to paper pái (cards) or bone pái (tiles); but there is no difference in play between these, as either serves to hide one face from the other players with identical backs. Card games are examples of imperfect information games as opposed to Chess or Go.

Many western scholars, like William Henry Wilkinson, Stewart Culin, Thomas F. Carter, and Michael Dummett attribute to the Chinese the invention of playing cards. Michael Dummett also contends that the concept of suits and the idea of trick-taking games were invented in China.[5] Trick-taking games eventually became multi-trick games. These then evolved into the earliest type of rummy games during the eighteenth century. By the end of the monarchy, the vast majority of traditional Chinese card games were of the draw-and-discard or fishing variety. Chinese playing cards have been spread into Southeast Asia by Chinese immigrants.[6]

Earliest references

The leaf game played from the reign of Emperor Yizong of Tang in 868 to the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) is often mistaken for a card game but it is described as a type of Shengguan Tu, a board game played with dice in which players consulted the leaves (pages) of a book. Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072) and Li Qingzhao (1084 – c. 1155) recorded that the leaf game's rules were lost by their time. The writer Yáng Yì (974-1020) and his friends are the last known players of the leaf game.[1]

The earliest unambiguous reference to playing cards is from a 1320 legal compilation, the Da Yuan shengzheng guochao dianzhang (大元聖政國朝典章), during the Yuan dynasty. It refers to a 17 July 1294 case in which two gamblers, Yan Sengzhu and Zheng Zhugou, were arrested in Shandong along with nine of their paper playing cards and the woodblocks used to print them.[1]

Domino cards

Chinese dominoes first appeared around the Southern Song dynasty and are derived from all twenty-one combinations of a pair of dice. They became available in card format around 1600 in Anhui.[7] Though not visually apparent, they are divided into two suits: civil and military (originally Chinese and barbarian respectively until the Qing dynasty). The invention of the concept of suits increased the level of strategy in trick-taking games; the card of one suit cannot beat the card of another suit regardless of its rank. The idiosyncratic ranking and suits come from Chinese dice games.

Domino card decks come in different sizes. Smaller decks are used in trick-taking and banking games. 32-card decks, with the civil suit doubled, are used to play Tien Gow and Pai Gow. Larger decks, for rummy or fishing games, may have well over a hundred cards and can include wild cards.

Although originating from tiles, domino card games inspired the creation of a tile game, Digging Flowers. Unlike regular domino tiles, these are short and squat allowing them to stand upright like mahjong tiles. This is a fairly old game, possibly preceding mahjong by decades if not a century.[4]

Money-suited cards

Money-suited cards have attracted the most attention from scholars. They are considered to be the ancestors of most of the world's playing cards. Each suit represents a different unit of currency. Lu Rong (1436–1494) described a four-suited 38-card deck:

- Cash or Coins: 1 to 9 Cash

- Strings of Cash: 1 to 9 Strings

- Myriads of Strings: 1 to 9 Myriad

- Tens of Myriads: 20 to 90 Myriad, Hundred Myriad, Thousand Myriad, and Myriad Myriad (11 cards in total)

There is no 10 Myriad card as it would share the same name as its suit. By the late 16th-century, the suit of Cash added two more cards: Half Cash and Zero Cash. The Cash suit was also in reverse order with the lower number cards beating the higher. This feature also appeared in other early card games like Ganjifa, Tarot, Ombre, and Maw. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the suit of Myriads and Tens depicted characters from the novel the Water Margin which is why they were also called Water Margin cards.[lower-alpha 1] They were also known as Madiao cards after one of the most popular games. The suits of Cash and Strings derive their pips from early Chinese banknotes. Some cards, most commonly the highest and lowest of each suit, will have a red stamp mimicking banknote seals. On both ends of some decks are markings that serve as indices to let players fan their cards.

From at least the 17th-century, games played with stripped decks became more popular. This was done by removing the suit of Tens save for the Thousand Myriad as in the game of Khanhoo. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Thousand Myriad, Half Cash, and Zero Cash took on new identities as the suitless Old Thousand, White Flower, and Red Flower respectively. They are sometimes joined by a "Ghost" card. The Myriad Myriad card disappeared by the late 19th century. During the Qing dynasty, draw-and-discard games became more popular and the 30-card deck was often multiplied with each card having two to five copies. Jin Xueshi noted that the three-suited decks were ten times more popular than four-suited ones prior to 1783, a disparity which has since significantly increased.[9] Mahjong, which also exists in card format, was derived from these types of games during the middle of the 19th century.

Four-suited decks still exist and are used by the Hakka to play Six Tigers, a multi-trick game. Six Tigers decks lack illustrations and instead just have ideograms of the rank and suit of each card.[10] Another structurally similar deck is Bài Bất found in Vietnam; its three-suit version is Tổ tôm. These Vietnamese cards were redesigned by Camoin of Marseilles during French colonial rule to depict people wearing traditional Japanese costumes from the Edo period.

Direct foreign derivatives include Bài chòi in Vietnam, Pai Tai in Thailand, and Ceki or Cherki in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. Korean Tujeon cards were possibly a descendant.[11] Ultimately, all four-suited decks (especially Italian and Spanish suited packs) are indirectly descended from the money-suited system through Mamluk playing cards.

Song dynasty coin

Song dynasty coin Song banknote

Song banknote Strings of coins

Strings of coins Ming banknote

Ming banknote Myriad Myriad card depicting Song Jiang as illustrated by Chen Hongshou, also used as a wine card.

Myriad Myriad card depicting Song Jiang as illustrated by Chen Hongshou, also used as a wine card. Madiao cards in the collection of Skoklosters slott

Madiao cards in the collection of Skoklosters slott Various types of Money-suited playing cards

Various types of Money-suited playing cards

Wine cards

If a loose definition of "card game" is used, then wine cards are arguably the earliest playing cards since they originate in the Tang dynasty (618-907). They are used in drinking games involving rice wine. Players simply draw or are dealt a card and follow its instructions such as drinking a certain number of cups or making someone else drink. The popularity of wine cards peaked from the 16th to mid-17th centuries.[1][4] "Eight Immortals Wine Cards" are still used in Sichuan. The game uses nine cards, the eponymous Eight Immortals and one for the poet Li Bai, a member of the Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup.[12][13]

Some cards have illustrations and/or poetry on them. During the Ming dynasty, most packs were printed as dual-use decks, which allowed them to be used just like money-suited playing cards for other card games.[14]

Character cards

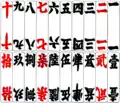

Character cards, printed with Chinese characters, first appeared during the middle of the Qing dynasty. There are several types of character cards but are all used to play rummy-like games.[15]

Number cards are quite similar to Six Tigers packs but each deck contains only two suits and includes rank 10. Both suits are labelled in Chinese numerals but one is in ordinary script while the other is in the financial or formal script. Some decks come with special suitless cards. There are 4 copies of each card.

Great Man cards are based on a copybook called "On the Great Man (Confucius)" used by students from the Tang to the Qing dynasty and mentioned in Lu Xun's novel Kong Yiji. There are 24 or 25 series of cards with each series based on a character from that book. Each series contains four or five identical cards. One variation known as 3-5-7 decks, contain 27 different series but with an uneven number of cards, some have two, three, or five cards with the total being 110 cards.

Doll cards contain eight series of cards repeated eight times. One card from each series is a special version of the card differentiated from the rest by depicting a human or doll. Each series is marked by one character that when strung together forms a blessing. Included in each deck is a ninth characterless series with seven cards showing one doll and one card showing two dolls. They are found in Sichuan and Chongqing.

Unlike other types of Chinese cards, they have not spread to other countries and are largely confined to southern China.

Chess cards

Cards based on xiangqi (also known as Chinese chess) appeared during the nineteenth century. They are generally divided into two categories, those with two suits known as red or fishing cards, and those with four suits known as four color cards. Each suit contains cards named after the seven different chessmen. Some decks have multiple copies of each card and may also contain "gold" wild cards. Most games are rummy-like but the two-suited tam cúc in Vietnam is a multi-trick game.

Like money-suited cards with mahjong tiles, there are tile versions of chess cards. In Taiwan, two-suited versions are used to play xiangqi mahjong while the four-suited ones are found in Malaysia.

Footnotes

- Lu Rong attributes the characters to the Miscellaneous Observations from the Year of Guixin (癸辛雜識) and Old Incidents in the Xuanhe Period of the Great Song Dynasty (大宋宣和遺事).[8] These are precursors to the Water Margin, which was not externally attested until 1524. Some of the names and characters from his deck are different from later ones.

References

- Lo, Andrew. (2000). The Game of Leaves: An Inquiry into the Origin of Chinese Playing Cards. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 63(3), 389–406.

- Lo, Andrew (2000), The Late Ming Game of Ma Diao, The Playing-Card (XXIX, No. 3), pp. 115–136, The International Playing-Card Society.

- Parlett, David. The Chinese "Leaf Game". Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- Lo, Andrew (2004) 'China's Passion for Pai: Playing Cards, Dominoes, and Mahjong.' In: Mackenzie, C. and Finkel, I., (eds.), Asian Games: The Art of Contest. New York: Asia Society, pp. 217-231.

- Michael Dummett, The Game of Tarot, London, p. 34-39. Carlo Penco (2013). Dummett and the Game of Tarot at Academia.edu. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Mann, Sylvia (1990). All Cards on the Table. Leinfelden: Jonas Verlag. pp. 200–208.

- Lo, Andrew (2003). "Pan Zhiheng's 'Xu Yezi Pu' - Part 2". The Playing-Card. 31 (6): 281–284.

- Bentley, Tamara Heimarck (2012). The Figurative Works of Chen Hongshou (1599-1652): Authentic Voices, Expanding Markets. Farnham (GB) Burlington (Vt.): Ashgate. pp. 80&82. ISBN 9780754666721.

- Dummett, Michael (1980). The Game of Tarot. London: Duckworth. pp. 34–39.

- Prunner, Gernot (1969). Ostasiatische Spielkarten. Bielefeld: Dt. Spielkartenmuseum. pp. 4–13.

- Yi, I-Hwa (2006). Korea's Pastimes and Customs: A Social History (1st American ed.). Hong Kong: Hangilsa Publishing Co. p. 29.

- "行酒令:中国酒文化中色彩卓异的奇葩". www.cnwinenews.com. China Wine News. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- "【民俗】"即席作歌",老成都人在饭桌上爱玩这种游戏". scdfz.sc.gov.cn. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Lo, Andrew (2007). "Literati Culture in Ming Dynasty Drinking Games Using Cards" (PDF). National Central University Journal of Humanities. 31: 243–288. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- British Museum (1901). Catalogue of the collection of playing cards bequeathed to the Trustees of the British museum by the late Lady Charlotte Schreiber. London: Longmans. pp. 184–194.

External links

- Chinese playing cards at World of Playing Cards

- Cards of China and Hong Kong and Southeast Asian cards at Andy's Playing Cards

- Money-suited playing cards at The Mahjong Tile Set

- Chinese and Southeast Asian playing cards and tiles at onebadcards

- Chinese traditional card games category at Wikipedia's Chinese language site

- Detailed scans of complete deck of traditional Chinese cards

- Detailed scans of complete deck of Luk Fu/Six Tigers cards