Chiribiquete National Park

Chiribiquete National Natural Park (Spanish: Parque Nacional Natural (PNN) Serranía de Chiribiquete) is the largest national park in Colombia and the largest tropical rainforest national park in the world. It was established on 21 September 1989 and has been expanded twice, first in August 2013 and then in July 2018.[1][2][3][4] The park occupies about 43,000 km2 (17,000 sq mi) and includes the Serranía de Chiribiquete mountains and the surrounding lowlands, which are covered by tropical moist forests, savannas and rivers.[1][4]

| Chiribiquete National Natural Park | |

|---|---|

| PNN Serranía de Chiribiquete | |

Tepui in the Park | |

Map of the national park | |

| Nearest city | San José del Guaviare |

| Coordinates | 0°31′31″N 72°47′50″W |

| Area | 43,000 km2 (17,000 sq mi) |

| Established | 1989 |

| Official website | |

| Official name | Chiribiquete National Park – “The Maloca of the Jaguar” |

| Type | Mixed |

| Criteria | (iii), (ix), (x) |

| Designated | 2018 (42nd session) |

| Reference no. | 1174 |

| Region | South America |

History

Chiribiquete National Natural Park was established on 21 September 1989. The park was expanded from the previous 13,000 km2 (5,000 sq mi) to 28,000 km2 (11,000 sq mi) on 21 August 2013.[1][3] Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos announced that Chiribiquete National Park would be expanded by 15,000 km2 (5,800 sq mi) on 21 February 2018.[5] The park was expanded to 43,000 km2 (17,000 sq mi) and declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO on 2 July 2018.[4][6]

Rock art

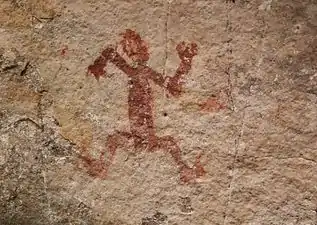

The region is incredibly biodiverse and hosts a diverse array of rock art.[3][4][5][7] More than 600,000 traces of over 75,000 petroglyphs and pictographs have been made by indigenous people on the walls of the 60 rock shelters from 20,000 BCE, and are still made nowadays by the uncontacted peoples protected by the National Park.[2][7] The rock art was produced until the 16th century. Some of the paintings were first photographed by geologist Jaime Galvis between 1986 and 1987. Further research was carried out by Carlos Castaños, former director of the National Natural Parks System of Colombia, and Dutch geologist and paleontologist Thomas van der Hammen from 1990 to 1992.[7][8] British wildlife filmmaker Mike Slee and Colombian photographer and explorer Francisco Forero Bonell photographed and filmed the rock paintings on the vertical rock faces within the park in 2014.[7][9]

Gallery

Geography

Chiribiquete National Park is located in the northwest of the Colombian Amazon in the departments of Caquetá and Guaviare.[2] It is in the jurisdictions of the municipalities of Solano, Cartagena del Chairá and San Vicente del Caguán in Caquetá, and Calamar and San José del Guaviare in Guaviare. It is bordered by the Tunia River (Macaya River) in the northeast, which forms the Apaporís River after its confluence with the Ajaju River at a point called Dos Ríos.[10] The park's boundaries are formed by the Apaporís, Gunaré and Amú Rivers in the east, the Mesay and Yari Rivers in the south, and the Hiutoto, Tajisa, Ajaju and Ayaya Rivers in the west.[4][10][11]

Chiribiquete National Park is situated in the western region of the Guiana Shield, east of the Eastern Cordillera, north of the Amazonian plains, west of the Upper Río Negro, and south of the savannas of the Orinoquía.[1] Elevations in the park range from about 200 to 1,000 metres above sea level.[1][11] It contains geological formations that are made up of plateaus and steep rocky structures. The formations are divided into three different sections: the Northern Massif, the Central Massif and Iguaje Messas.[11] The park is well known for its tepuis, table-top mountains that abruptly rise from the forest.[2] The mountain ridge of Chiribiquete is an important remnant of the rocky chain belonging to the Precambrian and Paleozoic formations that make up the Guiana Shield.[12][13]

Biogeographically, Chiribiquete is located in the Guyanas. It contains many different biomes, including flooded savannas and forests, tropical savannas, shrublands and tropical moist forests.[1][10][11]

Hydrology

Chiribiquete National Park contains the drainage basins of the Mesay, Cuñare, San Jorge and Amú Rivers. Most of the rivers in the park are tributaries of the Caquetá River, which is in turn a tributary of the Amazon River. Many of the rivers are called blackwater rivers because their waters have a dark colour due to the leeching of sediments from the surrounding soil.[11]

Climate

Chiribiquete National Natural Park has a tropical climate and gets about 4,500 mm of precipitation per year. The park has high levels of cloud cover due to the geographic orientation of the Serranía de Chiribiquete mountains. Rainfall is lowest between December and February, and highest between April and July. The annual average temperature is 24 °C (75 °F) with strong fluctuations between day and night. During the dry months, temperatures can rise to 32 °C (90 °F) during the day, and fall to 20 °C (68 °F) at night. The temperature difference between the lower and higher altitudes of the park is also very high. Temperatures can reach 35 °C (95 °F) in the lower altitudes and drop to 2 °C (36 °F) in the higher altitudes. The average humidity is 40% at daytime and rises to 100% at nighttime.[11][14][15]

Flora

Chiribiquete is home to 30% of the ecosystems and flora of the Colombian Amazon, and researchers have discovered 1,801 plant species in the park to date.[16] The tropical moist forests of Chiribiquete are highly developed and can reach great heights, with certain trees growing up to 40 m (130 ft). The most common trees are the Amazon tree-grape (Pourouma cecropiifolia), guamo (Inga acrocephala), ucuuba (Virola sebifera), syringe tree (Hevea guianensis) and capinuri (Pseudolmedia laevis). The undergrowth is very dense and host to a wide variety of parasitic and epiphytic plants. In the mountains, thickets of shrubs measuring between 12 and 15 m (39 and 49 ft) can be found growing on sandy soil. Places with sparse soil cover, like waterfalls and rocky surfaces, are home to many endemic plants, including the monotypic genus Senefelderopsis, Hevea nitida var. toxicodendroides, Graffenrieda fantastica and Vellozia tubiflora.[11]

Fauna

Researchers have discovered 209 butterfly species, 238 fish species, 57 amphibian species, 60 reptile species, over 410 bird species and 82 mammal species in Chiribiquete to date, many of which are threatened and endemic to the region.[2][3][16] The region is known for hosting high levels of endemism of amphibians and freshwater fish. It also hosts about 30% of the Colombian Amazon's bat diversity and 10% of the country's butterfly diversity.[16]

Birds

The most notable birds in Chiribiquete are the Guianan cock-of-the-rock, scarlet macaw, green-and-rufous kingfisher, Amazon kingfisher, ringed kingfisher, rufous motmot, oilbird, and the endemic Chiribiquete emerald hummingbird.[10][11] Other notable birds in the park are several species of tinamous, curassows in the genus Crax, and motmots in the genus Momotus. The harpy eagle and speckled chachalaca can also be commonly seen in the park.[11]

Mammals

Researchers have discovered 52 species of bats in Chiribiquete to date, which represents about 30% of the Colombia Amazon's bat diversity. Notable bats include dog-like bats, mouse-eared bats, bulldog bats, short-tailed fruit bats, and the Marinkelle's sword-nosed bat.[10][11][16][17] Some of the carnivorans in the park are the giant otter, neotropical otter, ocelot, cougar and jaguar. The park is home to 8 species of primates, including the white-fronted capuchin, tufted capuchin, common squirrel monkey, Spix's night monkey, brown woolly monkey and Venezuelan red howler monkey. It is also home to armadillos in the genus Dasypus, the giant anteater, black agouti, lowland paca, Amazon river dolphin, white-lipped peccary and Brazilian tapir.[2][10][11]

References

- "Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia". Government of Colombia. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- "Chiribiquete National Park– "The Maloca of the Jaguar"". UNESCO. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- "Colombia makes history with huge expansion of largest national park". International Union for Conservation of Nature. 25 September 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- "Colombia's Serranía de Chiribiquete is now the world's largest tropical rainforest national park". World Wide Fund for Nature. 2 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Alsema, Adriaan (22 February 2018). "Colombia's biggest national park to become 1.5 million hectares bigger". Colombia Reports. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- "Four sites added to UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO. 1 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Patiño, José Alberto Mojica (7 July 2015). "Hallado tesoro arqueológico en el Parque Natural Chiribiquete". El Tiempo. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Plotkin, Mark (2 October 2013). "'Lost Tribes' Saved through Creation of Massive Colombian Park (Op-Ed)". Live Science. Purch. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Alberge, Dalya (20 June 2015). "World's most inaccessible art found in the heart of the Colombian jungle". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- "Important Bird Areas factsheet: Parque Nacional Natural Chiribiquete". BirdLife International. 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- Sesana, Laura (2006). Colombia Natural Parks. Bogotá: Villegas Editores. pp. 389–398. ISBN 9588156874.

- "National Natural Parks: Chiribiquete". Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- Hammond, David S. (2005). Tropical Foresrs of the Guiana Shield. Wallingford, Oxfordshire: Cabi Publishing. ISBN 1845930924.

- Uribe, Carlos Castaño (1999). Sierras y Serranías de Colombia. Cali: Banco de Occidente Credencial. ISBN 9589674909.

- Estrada, Javier Estrada; Fuertes, Javier (January 1993). "Estudios botanicos en la Guayana colombiana, IV. Notas sobre la vegetacion y la flora de la Sierra de Chiribiquete" (PDF). Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales. 18 (71): 483–497.

- "Serranía del Chiribiquete National Park Factsheet" (PDF). WWF. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Mantilla-Meluk, Hugo; Montenegro, Olga (July–December 2016). "A new species of Lonchorhina (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) from Chiribiquete, Colombian Guayana". Neotropical Biodiversity. 6 (2): 171–187. doi:10.18636/bioneotropical.v6i2.576. eISSN 2256-5426. ISSN 2027-8918.

.svg.png.webp)