Harpy eagle

The harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) is a neotropical species of eagle. It is also called the American harpy eagle to distinguish it from the Papuan eagle, which is sometimes known as the New Guinea harpy eagle or Papuan harpy eagle.[5] It is the largest and most powerful raptor found throughout its range,[6] and among the largest extant species of eagles in the world. It usually inhabits tropical lowland rainforests in the upper (emergent) canopy layer. Destruction of its natural habitat has caused it to vanish from many parts of its former range, and it is nearly extirpated from much of Central America. In Brazil, the harpy eagle is also known as royal-hawk (in Portuguese: gavião-real).[7] The genus Harpia, together with Harpyopsis and Morphnus, form the subfamily Harpiinae.

| Harpy eagle | |

|---|---|

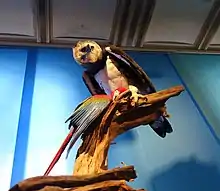

| |

| At the Parque das Aves in the Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Subfamily: | Harpiinae |

| Genus: | Harpia Vieillot, 1816 |

| Species: | H. harpyja |

| Binomial name | |

| Harpia harpyja | |

| |

| The harpy eagle is rare throughout its range, which extends from Mexico to Brazil (throughout its territory)[4] and Argentina (only the north). (note: map distribution in Trinidad and Tobago and ABC islands is erroneous) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

The harpy eagle was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae as Vultur harpyja,[8] after the mythological beast harpy. The only member of the genus Harpia, the harpy eagle is most closely related to the crested eagle (Morphnus guianensis) and the New Guinea harpy eagle (Harpyopsis novaeguineae), the three composing the subfamily Harpiinae within the large family Accipitridae. Previously thought to be closely related, the Philippine eagle has been shown by DNA analysis to belong elsewhere in the raptor family, as it is related to the Circaetinae.[9]

The specific name harpyja and the word "harpy" in the common name both come from Ancient Greek harpyia (ἅρπυια). They refer to the harpies of Ancient Greek mythology. These were wind spirits who flew the dead to Hades or Tartarus, purported to have the lower body and talons of a raptor and the head of a woman, standing anywhere from the height of a tall child to as high as a grown man; some depictions have the creatures possessing an eagle-like body with the exposed breasts of an elderly female human, a giant wingspan and the head of a grotesque, sharp-toothed, mutant eagle—something more akin to a goblin with wings.[10]

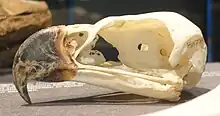

Description

The upperside of the harpy eagle is covered with slate-black feathers, and the underside is mostly white, except for the feathered tarsi, which are striped black. A broad black band across the upper breast separates the gray head from the white belly. The head is pale grey, and is crowned with a double crest. The upperside of the tail is black with three gray bands, while the underside of it is black with three white bands. The irises are gray or brown or red, the cere and bill are black or blackish and the tarsi and toes are yellow. The plumage of males and females is identical. The tarsus is up to 13 cm (5.1 in) long.[11][12]

Female harpy eagles typically weigh 6 to 9 kg (13 to 20 lb).[13][14][11][15] One source states that adult females can weigh up to 10 kg (22 lb).[16] An exceptionally large captive female, "Jezebel", weighed 12.3 kg (27 lb).[17] Being captive, however, this large female may not be representative of the weight possible in wild harpy eagles due to differences in the food availability.[18][19] The male, in comparison, is much smaller and may range in weight from 4 to 6 kg (8.8 to 13.2 lb).[13][11][15][14] The average weight of adult males has been reported as 4.4 to 4.8 kg (9.7 to 10.6 lb) against an average of 7.3 to 8.3 kg (16 to 18 lb) for adult females, a 35% or higher difference in mean body mass.[14][20][21] Harpy eagles may measure from 86.5 to 107 cm (2 ft 10.1 in to 3 ft 6.1 in) in total length[12][15] and have a wingspan of 176 to 224 cm (5 ft 9 in to 7 ft 4 in).[11][12] Among the standard measurements, the wing chord measures 54–63 cm (1 ft 9 in – 2 ft 1 in), the tail measures 37–42 cm (1 ft 3 in – 1 ft 5 in), the tarsus is 11.4–13 cm (4.5–5.1 in) long, and the exposed culmen from the cere (the beak) is 4.2 to 6.5 cm (1.7 to 2.6 in).[11][22][23] Mean talon size is 8.6 cm (3.4 in) in males, and 12.3 cm (4.8 in) in females.[24]

It is sometimes cited as the largest eagle alongside the Philippine eagle, which is somewhat longer on average (between sexes averaging 100 cm (3 ft 3 in)) but weighs slightly less, and the Steller's sea eagle, which is perhaps slightly heavier on average (mean of three unsexed birds was 7.75 kg (17.1 lb)).[10][21][25]

The harpy eagle may be the largest bird species to reside in Central America, though large water birds such as American white pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) and jabirus (Jabiru mycteria) have scarcely lower mean body masses.[21] The wingspan of the harpy eagle is relatively small, though the wings are quite broad, an adaptation that increases maneuverability in forested habitats and is shared by other raptors in similar habitats. The wingspan of the harpy eagle is surpassed by several large eagles that live in more open habitats, such as those in the Haliaeetus and Aquila genera.[11] The extinct Haast's eagle was significantly larger than all extant eagles, including the harpy.[26]

This species is largely silent away from the nest. There, the adults give a penetrating, weak, melancholy scream, with the incubating males' call described as "whispy screaming or wailing".[27] The females' calls while incubating are similar, but are lower-pitched. While approaching the nest with food, the male calls out "rapid chirps, goose-like calls, and occasional sharp screams". Vocalization in both parents decreases as the nestlings age, while the nestlings become more vocal. The nestlings call chi-chi-chi...chi-chi-chi-chi, seemingly in alarm in response to rain or direct sunlight. When humans approach the nest, the nestlings have been described as uttering croaks, quacks, and whistles.[28]

Distribution and habitat

Relatively rare and elusive throughout its range, the harpy eagle is found from southern México (incl. Chiapas, Oaxaca and the Yucatán states) and south through Central America, into South America to as far south as Argentina. They can still be seen by tourists and locals in Costa Rica and Panamá. As their preferred habitat is rainforest, they nest and hunt predominantly in the emergent layer. The eagle is most common in Brazil, where it is found across the entire country.[29] With the exception of some areas of the aforementioned Panamá and Costa Rica, the species is nearly extinct in Central America, likely due to the logging industry’s decimation of much of the Meso-American rainforests. Their habitat is expected to decline further due to climate change.[30] The harpy eagle prefers tropical, lowland rainforests and may also choose to nest within such areas from the canopy to the emergent vegetation. They typically occur below an elevation of 900 m (3,000 ft), but have been recorded at elevations up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft).[2] Within the forests, they hunt in the canopy or, rarely, on the ground, and perch on emergent trees to scout for prey. They do not generally occur in disturbed areas, avoiding humans whenever possible, but regularly visit semi-open forest and pasture mosaic, in hunting forays.[31] Harpies, however, can be found flying over forest borders in a variety of habitats, such as cerrados, caatingas, buriti palm stands, cultivated fields, and cities.[32] They have recently been found in areas where high-grade forestry is practiced.

Behavior

Feeding

Full grown harpy eagles are at the top of a food chain.[33] They possess the largest talons of any living eagle and have been recorded as carrying prey weighing up to roughly half of their own body weight.[11] This allows them to snatch from tree branches a live sloth and other large prey items. Most commonly, harpy eagles use perch hunting, in which they scan for prey activity while briefly perched between short flights from tree to tree.[11] Upon spotting prey, the eagle quickly dives and grabs it. Sometimes, harpy eagles are "sit-and-wait" predators (common in forest-dwelling raptors), perching for long periods on a high point near an opening, a river, or a salt lick, where many mammals go to attain nutrients.[11] On occasion, they may also hunt by flying within or above the canopy. They have also been observed tail-chasing: pursuing another bird in flight, rapidly dodging among trees and branches, a predation style common to hawks (genus Accipiter) that hunt birds.[11]

A recent literature review and research using camera traps list a total of 116 prey species.[34][35] Its main prey are tree-dwelling mammals, and a majority of the diet has been shown to focus on sloths.[36] Research conducted by Aguiar-Silva between 2003 and 2005 in a nesting site in Parintins, Amazonas, Brazil, collected remains from prey offered to the nestling by its parents. The researchers found that 79% of the harpy's prey was accounted for by sloths from two species: 39% brown-throated sloth (Bradypus variegatus), and 40% Linnaeus's two-toed sloth (Choloepus didactylus).[37] Similar research in Panama, where two captive-bred subadults were released, found that 52% of the male's captures and 54% of the female's were of two sloth species (brown-throated sloth and Hoffmann's two-toed sloth (Choloepus hoffmanni).[38] Harpy eagles are capable of hunting all size of sloths, including full-grown adult two-toed sloths weighing up to 9 kg (20 lb).[39]

Another major prey of harpy eagles is monkeys. At several nests in Guyana, monkeys made up about 37% of the prey remains found at the nests.[41] Similarly, cebid monkeys made up 35% of the remains found at 10 nests in Amazonian Ecuador.[42] Monkeys regularly taken include capuchin monkeys, saki monkeys, howler monkeys, titi monkeys, squirrel monkeys, and spider monkeys. Smaller monkeys, such as tamarins and marmosets, are, however, seemingly ignored as prey by this species. [11] Small monkeys typically weighing between 1 and 4 kg (2.2 and 8.8 lb), such as Wedge-capped capuchin (Cebus olivaceus), tufted capuchin (Sapajus apella), and white-faced saki (Pithecia pithecia) are the most frequently taken.[34][43] Larger howler monkeys are also taken, mainly Colombian red howler (Alouatta seniculus), but also Guyanan red howler (Alouatta macconnelli) and mantled howler (Alouatta palliata).[34] These monkeys weigh between 5.5 and 8.2 kg (12 and 18 lb) in females and 7.2 to 9 kg (16 to 20 lb) in males, and female harpy eagles can take all age of these howlers, including adult males, while male harpy eagles tend to focus on juveniles.[44][45][46] In one study, breeding harpy eagles hunted Yucatán black howler (Alouatta pigra), the largest howler monkey which can weigh between 6.4 and 11.3 kg (14 and 25 lb), although the ages of the monkeys taken by these eagles are unknown.[47][48] Nevertheless, adults of other large monkeys can be taken by female harpy eagles, including woolly monkey (Lagothrix cana) and Peruvian spider monkey (Ateles chamek), and red-faced spider monkey (Ateles paniscus) which can weigh around 5.8 to 9.4 kg (13 to 21 lb) and possibly exceeding 10 to 11 kg (22 to 24 lb) in large males.[34][35][49][43][50]

Other partially arboreal and even land mammals are also preyed on given the opportunity. In the Pantanal, a pair of nesting eagles preyed largely on the porcupine (Coendou prehensilis) and the agouti (Dasyprocta azarae).[51] Both species of tamanduas (Tamandua mexicana & T. tetradactyla) are taken and armadillos, especially nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) are also taken,[34][35] as well as carnivores such as kinkajous (Potos flavus), coatis (Nasua nasua & N. narcia), tayras (Eira barbara), and occasionally margays (Leopardus wiedii) and crab-eating foxes (Cerdocyon thous).[11][34] In one instant, an adult greater grison (Galictis vittata) was killed and partly consumed by subadult female harpy eagle.[52] Those carnivoran prey species usually weigh around 1.4 to 7.2 kg (3.1 to 15.9 lb),[53][50] but there is a report that harpy eagles prey on possibly larger carnivores such as ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) and adult crab-eating raccoon respectively.[49][14] Other mammals, such as young peccaries, deer fawns, squirrels and opossums are additionally taken.[11]

The eagle may also attack bird species such as macaws: At the Parintins research site, the red-and-green macaw (Ara chloropterus) made up for 0.4% of the prey base, with other birds amounting to 4.6%.[37][54] Other parrots have also been preyed on, as well as cracids such as curassows and other birds like seriemas.[11] In one occasion, dependent juvenile male eagle quickly learned how to hunt black vultures (Coragyps atratus) and accounted for 9 of our 10 records of harpy predation on vultures.[35] Additional prey items reported include reptiles such as iguanas, tegus, snakes, and amphisbaenids.[11][15] In Suriname, green iguanas (Iguana iguana) can be important prey source, and predation on yellow-footed tortoise (chelonoidis denticulata) have been recorded twice.[34]

The eagle has been recorded as taking domestic livestock, including chickens, lambs, goats, and young pigs, but this is extremely rare under normal circumstances.[11] They control the population of mesopredators such as capuchin monkeys, which prey extensively on bird's eggs and which (if not naturally controlled) may cause local extinctions of sensitive species.[55]

Males usually take relatively smaller prey, with a typical range of 0.5 to 2.5 kg (1.1 to 5.5 lb) or about half their own weight.[11] The larger females take larger prey, with a minimum recorded prey weight of around 2.7 kg (6.0 lb). Adult female harpies regularly grab large male howler or spider monkeys or mature sloths weighing 6 to 9 kg (13 to 20 lb) in flight and fly off without landing, an enormous feat of strength.[11][56][57]

Prey items taken to the nest by the parents are normally medium-sized, having been recorded from 1 to 4 kg (2.2 to 8.8 lb).[11] The prey brought to the nest by males averaged 1.5 kg (3.3 lb), while the prey brought to the nest by females averaged 3.2 kg (7.1 lb).[28] In another study, floaters (i.e. birds not engaging in breeding at that time) were found to take larger prey, averaging 4.24 kg (9.3 lb), than those that were nesting, for which prey averaged 3.64 kg (8.0 lb), with prey species estimated to weigh a mean of 1.08 kg (2.4 lb) (for common opossum) to 10.1 kg (22 lb) (for adult crab-eating raccoon).[14] Overall, harpy eagle prey weigh between 0.3 kg and 6.5 kg, with the mean prey size equalling 2.6 ± 0.8 kg [58]

Breeding

In ideal habitats, nests would be fairly close together. In some parts of Panama and Guyana, active nests were located 3 km (1.9 mi) away from one another, while they are within 5 km (3.1 mi) of each other in Venezuela. In Peru, the average distance between nests was 7.4 km (4.6 mi) and the average area occupied by each breeding pairs was estimated at 4,300 ha (11,000 acres). In less ideal areas, with fragmented forest, breeding territories were estimated at 25 km (16 mi).[15] The female harpy eagle lays two white eggs in a large stick nest, which commonly measures 1.2 m (3.9 ft) deep and 1.5 m (4.9 ft) across and may be used over several years. Nests are located high up in a tree, usually in the main fork, at 16 to 43 m (52 to 141 ft), depending on the stature of the local trees. The harpy often builds its nest in the crown of the kapok tree, one of the tallest trees in South America. In many South American cultures, cutting down the kapok tree is considered bad luck, which may help safeguard the habitat of this stately eagle.[59] The bird also uses other huge trees on which to build its nest, such as the Brazil nut tree.[60] A nesting site found in the Brazilian Pantanal was built on a cambará tree (Vochysia divergens).[61]

No display is known between pairs of eagles, and they are believed to mate for life. A pair of harpy eagles usually only raises one chick every 2–3 years. After the first chick hatches, the second egg is ignored and normally fails to hatch unless the first egg perishes. The egg is incubated around 56 days. When the chick is 36 days old, it can stand and walk awkwardly. The chick fledges at the age of 6 months, but the parents continue to feed it for another 6 to 10 months. The male captures much of the food for the incubating female and later the eaglet, but also takes an incubating shift while the female forages and also brings prey back to the nest. Breeding maturity is not reached until birds are 4 to 6 years of age.[11][28][31] Adults can be aggressive toward humans who disturb the nesting site or appear to be a threat to their young.[62]

Status and conservation

Although the harpy eagle still occurs over a considerable range, its distribution and populations have dwindled considerably. It is threatened primarily by habitat loss due to the expansion of logging, cattle ranching, agriculture, and prospecting. Secondarily, it is threatened by being hunted as an actual threat to livestock and/or a supposed one to human life, due to its great size.[63] Although not actually known to prey on humans and only rarely on domestic stock, the species' large size and nearly fearless behaviour around humans reportedly make it an "irresistible target" for hunters.[15] Such threats apply throughout its range, in large parts of which the bird has become a transient sight only; in Brazil, it was all but wiped out from the Atlantic rainforest and is only found in appreciable numbers in the most remote parts of the Amazon basin; a Brazilian journalistic account of the mid-1990s already complained that at the time it was only found in significant numbers in Brazilian territory on the northern side of the Equator.[64] Scientific 1990s records, however, suggest that the harpy Atlantic Forest population may be migratory.[65] Subsequent research in Brazil has established that, as of 2009, the harpy eagle, outside the Brazilian Amazon, is critically endangered in Espírito Santo,[66] São Paulo and Paraná, endangered in Rio de Janeiro, and probably extirpated in Rio Grande do Sul (where a recent (March 2015) record was set for the Parque Estadual do Turvo) and Minas Gerais[67] – the actual size of their total population in Brazil is unknown.[68]

Globally, the harpy eagle is considered vulnerable by IUCN[2] and threatened with extinction by CITES (appendix I). The Peregrine Fund until recently considered it a "conservation-dependent species", meaning it depends on a dedicated effort for captive breeding and release to the wild, as well as habitat protection, to prevent it from reaching endangered status, but now has accepted the near threatened status. The harpy eagle is considered critically endangered in Mexico and Central America, where it has been extirpated in most of its former range; in Mexico, it used to be found as far north as Veracruz, but today probably occurs only in Chiapas in the Selva Zoque. It is considered as near threatened or vulnerable in most of the South American portion of its range; at the southern extreme of its range, in Argentina, it is found only in the Parana Valley forests at the province of Misiones.[69][70] It has disappeared from El Salvador, and almost so from Costa Rica.[71]

National initiatives

Various initiatives for restoration of the species are in place in various countries. Since 2002, the Peregrine Fund initiated a conservation and research program for the harpy eagle in the Darién Province.[72] A similar—and grander, given the dimensions of the countries involved—research project is occurring in Brazil, at the National Institute of Amazonian Research, through which 45 known nesting locations (updated to 62, only three outside the Amazonian basin and all three inactive) are being monitored by researchers and volunteers from local communities. A harpy eagle chick has been fitted with a radio transmitter that allows it to be tracked for more than three years via a satellite signal sent to the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research.[73] Also, a photographic recording of a nest site in the Carajás National Forest was made for the Brazilian edition of National Geographic Magazine.[74]

In Panama, the Peregrine Fund carried out a captive-breeding and release project that released a total of 49 birds in Panama and Belize.[75] The Peregrine Fund has also carried out a research and conservation project on this species since the year 2000, making it the longest-running study on harpy eagles.[13][76]

In Belize, the Belize Harpy Eagle Restoration Project began in 2003 with the collaboration of Sharon Matola, founder and director of the Belize Zoo and the Peregrine Fund. The goal of this project was the re-establishment of the harpy eagle within Belize. The population of the eagle declined as a result of forest fragmentation, shooting, and nest destruction, resulting in near extirpation of the species. Captive-bred harpy eagles were released in the Rio Bravo Conservation and Management Area in Belize, chosen for its quality forest habitat and linkages with Guatemala and Mexico. Habitat linkage with Guatemala and Mexico were important for conservation of quality habitat and the harpy eagle on a regional level. As of November 2009, 14 harpy eagles have been released and are monitored by the Peregrine Fund, through satellite telemetry.[77]

In January 2009, a chick from the all-but-extirpated population in the Brazilian state of Paraná was hatched in captivity at the preserve kept in the vicinity of the Itaipu Dam by the Brazilian/Paraguayan state-owned company Itaipu Binacional.[78] In September 2009, an adult female, after being kept captive for 12 years in a private reservation, was fitted with a radio transmitter before being restored to the wild in the vicinity of the Pau Brasil National Park (formerly Monte Pascoal NP), in the state of Bahia.[79]

In December 2009, a 15th harpy eagle was released into the Rio Bravo Conservation and Management Area in Belize. The release was set to tie in with the United Nations Climate Change Conference 2009, in Copenhagen. The 15th eagle, nicknamed "Hope" by the Peregrine officials in Panama, was the "poster child" for forest conservation in Belize, a developing country, and the importance of these activities in relation to climate change. The event received coverage from Belize's major media entities, and was supported and attended by the U.S. Ambassador to Belize, Vinai Thummalapally, and British High Commissioner to Belize, Pat Ashworth.[80]

In Colombia, as of 2007, an adult male and a subadult female confiscated from wildlife trafficking were restored to the wild and monitored in Paramillo National Park in Córdoba, and another couple was being kept in captivity at a research center for breeding and eventual release.[81] A monitoring effort with the help of volunteers from local Native American communities is also being made in Ecuador, including the joint sponsorship of various Spanish universities[82]—this effort being similar to another one going on since 1996 in Peru, centred around a native community in the Tambopata Province, Madre de Dios Region.[83] Another monitoring project, begun in 1992, was operating as of 2005 in the state of Bolívar, Venezuela.[84]

In human culture

_BHL41003954.jpg.webp)

The harpy eagle is the national bird of Panama and is depicted on the coat of arms of Panama.[86] The 15th harpy eagle released in Belize, named "Hope", was dubbed "Ambassador for Climate Change", in light of the United Nations Climate Change Conference 2009.[87][88]

The bird appeared on the reverse side of the Venezuelan Bs.F 2,000 note.

The harpy eagle was the inspiration behind the design of Fawkes the Phoenix in the Harry Potter film series.[89] A live harpy eagle was used to portray the now-extinct Haast's eagle in BBC's Monsters We Met.[90]

References and notes

- "Fossilworks: Harpia harpyja".

- BirdLife International (2022). "Harpia harpyja". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T22695998A197957213. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22695998A197957213.en. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- "Aves de Rapina BR | Gavião-Real (Harpia harpyja)". avesderapinabrasil.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-10. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- Tingay, Ruth E.; Katzner, Todd E. (23 February 2011). Rt-Eagle Watchers Z. Cornell University Press. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-0-8014-5814-9. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- The illustrated atlas of wildlife. University of California Press. 2009. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-520-25785-6.

- "Programa de Conservação do Gavião-real". gaviaoreal.inpa.gov.br. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 86.

V. occipite subcristato.

- Lerner, Heather R. L.; Mindell, David P. (November 2005). "Phylogeny of eagles, Old World vultures, and other Accipitridae based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 37 (2): 327–346. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.010. PMID 15925523. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- Piper, Ross (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-313-33922-6.

- Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, David A. (2001). Raptors of the world. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 717–719. ISBN 978-0-618-12762-7. Archived from the original on 2016-12-22. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

- Howell, Steve N. G. (30 March 1995). A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854012-0.

- "Size of Harpy Eagle | Rainforest Top Predator | Whitehawk Birding Blog". 2020-06-25. Archived from the original on 2020-06-28. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- Miranda, Everton B. P.; Campbell-Thompson, Edwin; Muela, Angel; Vargas, Félix Hernán (2018). "Sex and breeding status affect prey composition of Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja". Journal of Ornithology. 159 (1): 141–150. doi:10.1007/s10336-017-1482-3. S2CID 36830775.

- Thiollay, J. M. (1994). Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja). p. 191 in: del Hoy, J, A. Elliott, & J. Sargatal, eds. (1994). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 2. New World Vultures to Guineafowl. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona; ISBN 84-87334-15-6

- Trinca, C.T.; Ferrari, S.F. & Lees, A.C. "Curiosity killed the bird: arbitrary hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja on an agricultural frontier in southern Brazilian Amazonia" (PDF). Cotinga. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2013-03-28.

- Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- O'Connor, R. J. (1984). The Growth and Development of Birds, Wiley; ISBN 0-471-90345-0

- Arent, L.A. (2007). Raptors in Captivity, Hancock House, Washington; ISBN 978-0-88839-613-6

- Whitacre, D. F., & Jenny, J. P. (2013). Neotropical birds of prey: biology and ecology of a forest raptor community. Cornell University Press.

- Dunning, John B. Jr., ed. (2008). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses (2nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- Sagip Eagle, Gbgm-umc.org. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- Smithsonian miscellaneous collections (1862). Archive.org. Retrieved on 2013-03-09.

- Viloria, Ángel L.; Lizarralde, Manuel; Blanco, P. Alexander; Sharpe, Christopher J. (2021). "Ethno-ornithological notes and neglected references on the Harpy Eagle Harpia harpyja in western Venezuela". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 141 (2): 156–166. doi:10.25226/bboc.v141i2.2021.a6.

- Gamauf, A.; Preleuthner, M. & Winkler, H. (1998). "Philippine Birds of Prey: Interrelations among habitat, morphology and behavior" (PDF). The Auk. 115 (3): 713–726. doi:10.2307/4089419. JSTOR 4089419. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2019-06-27.

- Museum of New Zealand (1998). Giant eagle (Aquila moorei), Haast’s eagle, or Pouakai. Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine Accessed June 4, 2011.

- "Identification – Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja) – Neotropical Birds". Neotropical.birds.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-06-07. Retrieved 2013-05-13.

- Rettig, N. (1978). "Breeding behavior of the Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja)". Auk. 95 (4): 629–643. JSTOR 4085350. Archived from the original on 2014-12-03. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- "Gavião-real, uma das maiores aves de rapina do mundo – Terra Brasil". noticias.terra.com.br. Archived from the original on 2015-09-25. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- Sutton, Luke J.; Anderson, David L.; Franco, Miguel; McClure, Christopher J. W.; Miranda, Everton B. P.; Vargas, F. Hernán; Vargas González, José De J.; Puschendorf, Robert (July 2022). "Reduced range size and Important Bird and Biodiversity Area coverage for the Harpy Eagle ( Harpia harpyja ) predicted from multiple climate change scenarios". Ibis. 164 (3): 649–666. doi:10.1111/ibi.13046. hdl:10026.1/18797. ISSN 0019-1019. S2CID 245996767.

- Rettig, N.; Hayes, K. (1995). "Remote world of the harpy eagle". National Geographic. 187 (2): 40–49.

- Sigrist, Tomas (2013) Ornitologia Brasileira. Vinhedo: Avis Brasilis. ISBN 978-85-60120-25-3. p. 192

- Muñiz-López, R. (2017). "Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja) mortality in Ecuador" (PDF). Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment. 52 (1): 81–85. doi:10.1080/01650521.2016.1276716. S2CID 88504113. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-05-20. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- Miranda, Everton B. P. (2018). "Prey Composition of Harpy Eagles (Harpia harpyja) in Raleighvallen, Suriname". Tropical Conservation Science. 13: 194008291880078. doi:10.1177/1940082918800789.

- Miranda, Everton BP, et al. "Tropical deforestation induces thresholds of reproductive viability and habitat suitability in Earth’s largest eagles." Scientific Reports 11.1 (2021): 1-17.

- Santos, D. W. (2011). WA548962, Harpia harpyja (Linnaeus, 1758) Archived 2013-10-14 at the Wayback Machine. Wiki Aves – A Enciclopédia das Aves do Brasil.. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- Aguiar-Silva, F. Helena (2014). "Food Habits of the Harpy Eagle, a Top Predator from the Amazonian Rainforest Canopy". Journal of Raptor Research. 48 (1): 24–35. doi:10.3356/JRR-13-00017.1. S2CID 86270583.

- Touchton, Janeene M.; Yu-Cheng Hsu; Palleroni, Alberto (2002). "Foraging ecology of reintroduced captive-bred subadult harpy eagles (Harpia harpiya) on Barro Colorado Island, Panama" (PDF). Ornitologia Neotropical. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 9, 2008.

- Rettig, Neil L. "Breeding behavior of the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja)." The Auk 95.4 (1978): 629-643.

- Everton B. P. Miranda; Carlos A. Peres; Vítor Carvalho-Rocha; et al. (30 June 2021). "Tropical deforestation induces thresholds of reproductive viability and habitat suitability in Earth's largest eagles". Scientific Reports. 11. doi:10.1038/S41598-021-92372-Z. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8245467. Wikidata Q107387906.

- Izor, R.J. (1985). "Sloths and other mammalian prey of the Harpy Eagle". pp. 343–346 in G.G. Montgomery (ed.), The evolution and ecology of armadillos, sloths, and vermilinguas. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Muñiz-López, R., O. Criollo, and A. Mendúa. (2007). Results of five years of the "Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja) Research Program" in the Ecuadorian tropical forest. pp. 23–32 in K. L Bildstein, D. R. Barber, and A. Zimmerman (eds.), Neotropical raptors. Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, Orwigsburg, PA.

- Ford, Susan M., and Lesa C. Davis. "Systematics and body size: implications for feeding adaptations in New World monkeys." American Journal of Physical Anthropology 88.4 (1992): 415-468.

- Gil-da Costa, Ricardo. "Howler monkeys and harpy eagles: A communication arms race." Primate anti-predator strategies (2007): 289-307.

- Peres CA (1990) A harpy eagle successfully captures an adult male red howler monkey. Wilson Bull 102:560–561

- Márquez, Pilar Alexánder Blanco, and Blas Chacares. "El águila harpía (Harpia harpyja): Especie centinela de primates en la Reserva Forestal de Imataca." LA PRIMATOLOGÍA EN VENEZUELA: 145.

- Di Fiore, A.; Campbell, C. (2007). "The Atelines". In Campbell, C.; Fuentes, A.; MacKinnon, K.; Panger, M.; Bearder, S. (eds.). Primates in Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 155–177. ISBN 978-0-19-517133-4.

- Rotenberg, J. A., Marlin, J. A., Pop, L., & Garcia, W. (2012). First record of a Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja) nest in Belize. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 124(2), 292-297.

- Alvarez-Cordero, Eduardo. Biology and conservation of the Harpy Eagle in Venezuela and Panama. University of Florida, 1996.

- Emmons, L. H., and F. Feer. "Neotropical Rainforest Mammals-A Field Guide text." (1990).

- Aves de Rapina BR | Gavião-Real (Harpia harpyja) Archived 2010-07-20 at the Wayback Machine. Avesderapinabrasil.com. Retrieved on 2012-08-21.

- Casanova, Gabriel Enrique Maldonado, Ramiro Ninabanda, and Mayra Licuy. "Depredación de grisón grande (Galictis vittata) por Águila Harpía Harpia harpyja." Revista Ecuatoriana de Ornitología 8.1 (2022): 44-47.

- Hunter, Luke. Field guide to carnivores of the world. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

- Aguiar-Silva (2007). "Dieta do gavião-real Harpia harpyja (Aves: Accipitridae) em florestas de terra firme de Parintins, Amazonas, Brasil" Archived 2019-04-05 at the Wayback Machine. Thesis

- Shaner, K. (2011). Harpia harpyja Archived 2011-04-06 at the Wayback Machine (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed August 21, 2012

- San Diego Zoo's Animal Bytes: Harpy Eagle Archived 2007-10-13 at the Wayback Machine. Sandiegozoo.org. Retrieved on 2012-08-21.

- "Gavião-real". Brasil 500 Pássaros (in Portuguese). Eletronorte. Archived from the original on February 11, 2010. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- Aguiar-Silva, F. Helena; Sanaiotti, Tânia M.; Luz, Benjamim B. (2014). "Food Habits of the Harpy Eagle, a Top Predator from the Amazonian Rainforest Canopy". Journal of Raptor Research. 48: 24–35. doi:10.3356/JRR-13-00017.1. S2CID 86270583.

- Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- Hughes, Holly (29 January 2009). Frommer's 500 Places to See Before They Disappear. John Wiley & Sons. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-470-43162-7. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- Harpia (gavião-real) Archived 2010-07-20 at the Wayback Machine. Avesderapinabrasil.com. Retrieved on 2012-08-21.

- Vaughan, Adam (July 6, 2010). "Monkey-eating eagle divebombs BBC filmmaker as he fits nest-cam". guardian.co.uk. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- Talia Salanotti, researcher for the Brazilian National Institute of Amazonian Research, cf. O Globo, May the 13th. 2009; abridgement available at Maior águia das Américas, gavião-real sofre com destruição das florestas Archived 2012-10-12 at the Wayback Machine; on the random killing of harpies in frontier regions, see Cristiano Trapé Trinca, Stephen F. Ferrari and Alexander C. Lees Curiosity killed the bird: arbitrary hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja on an agricultural frontier in southern Brazilian Amazonia Archived 2011-04-28 at the Wayback Machine. Cotinga 30 (2008): 12–15

- "Senhora dos ares", Globo Rural, ISSN 0102-6178, 11:129, July 1996, pp. 40 and 42

- Alluvion of the Lower Schwalm near Borken Archived 2009-01-05 at the Wayback Machine. Birdlife.org. Retrieved on 2012-08-21.

- Where an adult male was observed in August 2005 at the preserve kept by mining corporation Vale do Rio Doce at Linhares: cf. Srbek-Araujo, Ana C.; Chiarello, Adriano G. (2006). "Registro recente de harpia, Harpia harpyja (Linnaeus) (Aves, Accipitridae), na Mata Atlântica da Reserva Natural Vale do Rio Doce, Linhares, Espírito Santo e implicações para a conservação regional da espécie". Revista Brasileira de Zoologia. 23 (4): 1264. doi:10.1590/S0101-81752006000400040.

- Nevertheless, in 2006, an adult female – probably during migration – was seen and photographed at the vicinity of Tapira, in the Minas Gerais cerrado: cf. Oliveira, Adilson Luiz de; Silva, Robson Silva e (2006). "Registro de Harpia (Harpia harpyja) no cerrado de Tapira, Minas Gerais, Brasil" (PDF). Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia. 14 (4): 433–434. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 2, 2010.

- Couto, Clarice. "Viva a Rainha". Globo Rural. 25 (288): 65. Archived from the original on 2014-08-19.

- The Misiones Green Corridor Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine. Redyaguarete.org.ar. Retrieved on 2012-08-21.

- For a map of the species historical and current range, see Fig. 1 in Lerner, Heather R. L.; Johnson, Jeff A.; Lindsay, Alec R.; Kiff, Lloyd F.; Mindell, David P. (2009). Ellegren, Hans (ed.). "It's not too Late for the Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja): High Levels of Genetic Diversity and Differentiation Can Fuel Conservation Programs". PLOS ONE. 4 (10): e7336. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7336L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007336. PMC 2752114. PMID 19802391.

- Weidensaul, Scott (2004). The Raptor Almanac: A Comprehensive Guide to Eagles, Hawks, Falcons, and Vultures. New York, New York: Lyons Press. pp. 280–81. ISBN 978-1-58574-170-0.

- Harpy Eagle Harpia harpyja Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine. Globalraptors.org. Retrieved on 2012-08-21.

- Projecto Gavião-real Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine INPA; Globo Rural, 25:288, page 62

- Rosa, João Marcos (2011-06-22). Mirada alemã: um olhar crítico sobre o seu próprio trabalho. abril.com.br

- Watson, Richard T.; McClure, Christopher J. W.; Vargas, F. Hernán; Jenny, J. Peter (March 2016). "Trial Restoration of the Harpy Eagle, a Large, Long-lived, Tropical Forest Raptor, in Panama and Belize". Journal of Raptor Research. 50 (1): 3–22. doi:10.3356/rapt-50-01-3-22.1. ISSN 0892-1016.

- "Harpy Eagle | The Peregrine Fund". peregrinefund.org. Archived from the original on 2020-06-29. Retrieved 2020-06-27.

- The Belize Harpy Eagle Restoration Program (BHERP). belizezoo.org

- G1 > Brasil – NOTÍCIAS – Ave rara no Brasil nasce no Refúgio Biológico de Itaipu Archived 2009-02-12 at the Wayback Machine. G1.globo.com. Retrieved on 2012-08-21.

- Revista Globo Rural, 24:287, September 2009, 20

- "The Importance of Hope, the Harpy Eagle". 7 News Belize. 2009-12-14. Archived from the original on 2010-07-22. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- Márquez C., Gast-Harders F., Vanegas V. H., Bechard M. (2006). Harpia harpyja (L., 1758) Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine. siac.net.co

- "Sponsorship and Exhibition at ATBC OTS" (PDF). International Conference Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation and the Organization for Tropical Studies. 23–27 June 2013, San José, Costa Rica. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2014.

- Piana, Renzo P. "The Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja) in the Infierno Native Community" Archived 2015-04-29 at the Wayback Machine. inkaways.com

- (in Spanish) Programa de conservación del águila arpía. Ecoportal.net (2005-12-15). Retrieved on 2012-08-21.

- Tozzer, Alfred M.; Allen, Glover M. Animal figures in the Maya codices. Retrieved 25 November 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Goldish, Meish (2007). Bald Eagles: A Chemical Nightmare. Bearport Publishing Company, Incorporated. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-59716-505-1.

- "Raptor Education Soars in Toledo". The Belize Zoo and Tropical Education Center. 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- "The Importance of Hope, the Harpy Eagle". 7 News Belize. December 14, 2009. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- Lederer, Roger J. (2007). Amazing Birds: A Treasury of Facts and Trivia about the Avian World. Barron's Educational Series, Incorporated. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-7641-3593-4.

- "Haast's eagle videos, news and facts". BBC. Archived from the original on 2012-01-14. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

External links

- Harpy eagle Facts and Pictures on AnimalSpot.net

- Harpy eagle videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- San Diego Zoo info about the harpy eagle

- Harpy eagle information and photo Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine

- The Peregrine Fund-Harpy Eagle