Voicing (music)

In music theory, voicing refers to two closely related concepts:

- How a musician or group distributes, or spaces, notes and chords on one or more instruments

- The simultaneous vertical placement of notes in relation to each other;[5] this relates to the concepts of spacing and doubling

It includes the instrumentation and vertical spacing and ordering of the musical notes in a chord: which notes are on the top or in the middle, which ones are doubled, which octave each is in, and which instruments or voices perform each note.

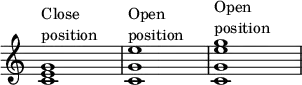

Vertical placement

The following three chords are all C-major triads in root position with different voicings. The first is in close position (the most compact voicing), while the second and third are in open position (that is, with wider spacing). Notice also that the G is doubled at the octave in the third chord; that is, it appears in two different octaves.

Examples

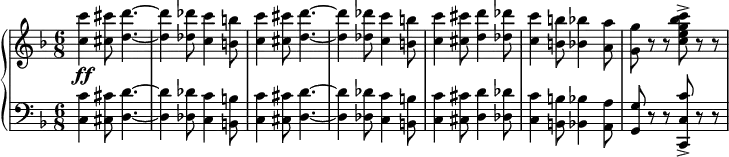

Many composers, as they developed and gained experience, became more enterprising and imaginative in their handling of chord voicing. For example, the theme from the second movement of Ludwig van Beethoven's early Piano Sonata No. 10 (1798), presents chords mostly in close position:

On the other hand, in the theme of the Arietta movement that concludes his last piano sonata, Piano Sonata No. 32, Op. 111 (1822), Beethoven presents the chord voicing in a much more daring way, with wide gaps between notes, creating compelling sonorities that enhance the meditative character of the music:

Philip Barford describes the Arietta of Op. 111 as "simplicity itself… its widely-spaced harmonization creates a mood of almost mystical intensity. In this exquisite harmonization the notes do not make their own track – the way we play them depends upon the way we catch the inner vibration of the thought between the notes, and this will condition every nuance of shading."[6] William Kinderman finds it "extraordinary that this sensitive control of sonority is most evident in the works of Beethoven's last decade, when he was completely deaf, and could hear only in his imagination."[7]

Another example of the later Beethoven's daring approach to voicing can be found in the second movement of his Hammerklavier Sonata, Op. 106. In the trio section of this movement (bars 48ff), Martin Cooper notes that “Beethoven has enhanced the strangeness of the effect by laying out much of the music four or five octaves apart, with no comfortable ‘filling’ between. This is a layout common in the works of his last years.” [8]

During the Romantic Era, composers continued further in their exploration of sonorities that can be obtained through imaginative chord voicing. Alan Walker draws attention to the quiet middle section of Chopin's Scherzo No. 1. In this passage, Chopin weaves a "magical" pianistic texture around a traditional Polish Christmas carol:[9]

Maurice Ravel's Pavane de la Belle au Bois Dormant from his 1908 suite Ma Mère l'Oye exploits the delicate transparency of voicing afforded through the medium of the piano duet. Four hands can cope better than two when it comes to playing widely spaced chords. This is especially apparent in bars 5–8 of the following extract:

Speaking of this piece (which also exists in an orchestral version), William Weaver Austin writes about Ravel's technique of "varying the sonority from phrase to phrase by telling changes of register."[10]

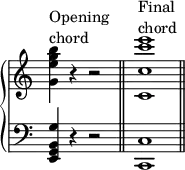

The two chords that open and close Igor Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms have distinctive sonorities arising out of the voicing of the notes. The first chord is sometimes called the Psalms chord. William W. Austin remarks:

The first and last chords of the Symphony of Psalms are famous. The opening staccato blast, which recurs throughout the first movement, detached from its surroundings by silence, seems to be a perverse spacing of the E minor triad, with the minor third doubled in four octaves while the root and fifth appear only twice, at high and low extremes... When the tonic C major finally arrives, in the last movement, its root is doubled in five octaves, its fifth is left to the natural overtones, and its decisive third appears just once, in the highest range. This spacing is as extraordinary as the spacing of the first chord, but with the opposite effect of super-clarity and consonance, thus resolving and justifying the first chord and all the horror of the miry clay.[11]

Some chord voicings devised by composers are so striking that they are instantly recognizable when heard. For example, The Unanswered Question by Charles Ives opens with strings playing a widely spaced G-major chord very softly, at the limits of audibility. According to Ives, the string part represents "The Silence of the Druids—who Know, See and Hear Nothing".

Doubling

In a chord, a note that is duplicated in different octaves is said to be doubled. (The term magadization is also used for vocal doubling at the octave, especially in reference to early music.) Doubling may also refer to a note or a melodic phrase that is duplicated at the same pitch, but played by different instruments.

Melodic doubling in parallel (also called parallel harmony) is the addition of a rhythmically similar or exact melodic line or lines at a fixed interval above or below the melody to create parallel movement.[12] Octave doubling of a voice or pitch is a number of other voices duplicating the same part at the same pitch or at different octaves. The doubling number of an octave is the number of individual voices assigned to each pitch within the chord. For instance, in the opening of John Philip Sousa's "Washington Post March",[13] the melody is "doubled" in four octaves.

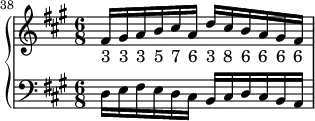

Consistent parallelism between melodic lines can impede the independence of the lines. For example, in m. 38 of the gigue from his English Suite No. 1 in A major, BWV 806, J.S. Bach avoids excessive parallel harmony in order to maintain the independence of the lines: parallel thirds (at the beginning) and parallel sixths (at the end) are not maintained throughout the entire measure, and no interval is in parallel for more than four consecutive notes.

Consideration of doubling is important when following voice leading rules and guidelines, for example when resolving to an augmented sixth chord never double either notes of the augmented sixth, while in resolving an Italian sixth it is preferable to double the tonic (third of the chord).[14]

Some pitch material may be described as autonomous doubling in which the part being doubled is not followed for more than a few measures often resulting in disjunct motion in the part that is doubling, for example, the trombone part in Mozart's Don Giovanni.[15]

In unison

Instrumental doubling plays a crucial role in orchestration. Near the start of Schubert's Symphony No. 8 (the "Unfinished" Symphony), the oboe and clarinet play a theme together in unison, an "evocative and uncommon combination,"[16] "an embodiment of melancholy... over a nervous shimmer of semiquavers in the strings".[17]

At the octave

The opening theme of the last movement of Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 24 is played throughout by the violins, but selected phrases are doubled, firstly by the flute playing an octave above; followed by the bassoon an octave below. Finally the violin is joined by both oboe and bassoon together, creating a doubling spanning three octaves:

The opening bars of the third movement of Janáček's Sinfonietta combine unison and octave doublings. The passage illustrates how subtle and carefully differentiated doubling can contribute to the sound of a delicate and nuanced orchestral texture:

In these three bars, the Bass Clarinet and the Tuba simultaneously sound a sustained pedal point on a low E flat, creating a distinctive blend of timbres. Similarly, the harp arpeggios are also doubled at the unison by the violas, while the first violins and ‘cellos double the main melody an octave apart.

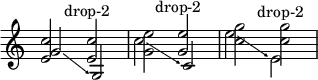

Drop voicings

One nomenclature for describing certain classes of voicings is the "drop-n" terminology, such as drop-2 voicings, drop-4 voicings, etc. (sometimes spelled without hyphens). This system views voicings as built from the top down (probably from horn-section arranging where the melody is a given). The implicit, non-dropped, default voicing in this system has all voices in the same octave, with individual voices numbered from the top down. The highest voice is the first voice or voice 1. The second-highest voice is voice 2, etc. This nomenclature doesn't provide a term for more than one voice on the same pitch.

A dropped voicing lowers one or more voices by an octave relative to the default state. Dropping the first voice is undefined—a drop-1 voicing would still have all voices in the same octave, simply making a new first voice. This nomenclature doesn't cover the dropping of voices by two or more octaves or having the same pitch in multiple octaves.

A drop-2 voicing lowers the second voice by an octave. For example, a C-major triad has three "drop-2 voicings". Reading down from the top voice, they are C E G, E G C, and G C E, which can be heard as the voicings supporting the first three melody notes (following the introductory phrase) of the Super Mario Bros. video game theme.[18]

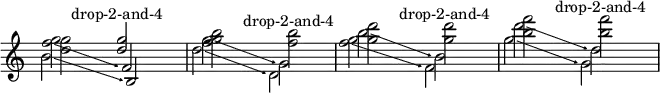

There are four drop-2-and-4 voicings for G 7. Reading down from the top voice, they are G D F B, B F G D, D G B F, and F B D G. Various drop combinations are possible, given enough voices, such as drop-3, drop-2-and-3, drop-5, drop-2-and-5, drop-3-and-5, etc.

Drop voicings are often employed by guitarists, as the perfect fourth intervals between the guitar's strings typically make most close position chords cumbersome and impractical to play, particularly in jazz where complex extensions are commonplace. While open chords are the most commonly employed voicings on the guitar and other fretted instruments for the volume and resonance they produce, the fingerings used for drop voicings on guitar are easily moved horizontally and vertically around the fingerboard, allowing more freedom for the guitarist to play chords in any key and in any area of the guitar's range, without the use of a capo. This facilitates easily playing chord progressions featuring modulation or chromatic movement between keys.

Sources

- Benward & Saker (2003), p. 269.

- Benward & Saker (2003), p. 274.

- Benward & Saker (2003), p. 276.

- Benward & Saker (2009), p. 74.

- Corozine, Vince (2002). Arranging Music for the Real World: Classical and Commercial Aspects. Pacific, MO: Mel Bay. p. 7. ISBN 0-7866-4961-5. OCLC 50470629.

- Barford, P. (1971). "The Piano Music – II". In Arnold, D. & Fortune, N. (eds.). The Beethoven Companion. London: Faber. p. 146.

- Kinderman, W. (1987). Beethoven's Diabelli Variations. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 64.

- Cooper, M. (1970, p.162) Beethoven, the Last Decade. Oxford University Press.

- Walker, A. (2018). Fryderyk Chopin, a Life and Times. London: Faber. p. 189.

- Austin, W. (1966). Music in the 20th Century. London: Dent. p. 172.

- Austin, W. (1966). Music in the 20th Century. London: Dent. p. 334.

- Benward & Saker (2009), p. 253.

- Benward & Saker (2003), p. 133.

- Benward & Saker (2009), p. 106.

- Guion, David M. (1988). The Trombone: Its History and Music, 1697–1811. Musicology: A Book Series, Vol. VI. Gordon and Breach. p. 133. ISBN 2-88124-211-1.

- Newbould, Brian (1997). Schubert, the Music and the Man. London: Gollancz. p. 377.

- Service, Tom (14 January 2014). "Symphony Guide: Schubert's Unfinished". The Guardian.

- "Super Mario Bros. Theme Song". Youtube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-22. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

Sources