Orchestration

Orchestration is the study or practice of writing music for an orchestra (or, more loosely, for any musical ensemble, such as a concert band) or of adapting music composed for another medium for an orchestra. Also called "instrumentation", orchestration is the assignment of different instruments to play the different parts (e.g., melody, bassline, etc.) of a musical work. For example, a work for solo piano could be adapted and orchestrated so that an orchestra could perform the piece, or a concert band piece could be orchestrated for a symphony orchestra.

_of_'Der_Freisch%C3%BCtz'_-_NGO4p1116.jpg.webp)

In classical music, composers have historically orchestrated their own music. Only gradually over the course of music history did orchestration come to be regarded as a separate compositional art and profession in itself. In modern classical music, composers almost invariably orchestrate their own work. Two notable exceptions to this are Ravel's orchestration of Mussorgsky's solo piano work Pictures at an Exhibition[1] and Malcolm Arnold's orchestration of William Walton's String Quartet in A minor, producing the latter's Sonata for Strings.[2]

However, in musical theatre, film music and other commercial media, it is customary to use orchestrators and arrangers to one degree or another, since time constraints and/or the level of training of composers may preclude them orchestrating the music themselves.

The precise role of the orchestrator in film music is highly variable, and depends greatly on the needs and skill set of the particular composer.

In musical theatre, the composer typically writes a piano/vocal score and then hires an arranger or orchestrator to create the instrumental score for the pit orchestra to play.

In jazz big bands, the composer or songwriter may write a lead sheet, which contains the melody and the chords, and then one or more orchestrators or arrangers may "flesh out" these basic musical ideas by creating parts for the saxophones, trumpets, trombones, and the rhythm section (bass, piano/jazz guitar/Hammond organ, drums). But, commonly enough, big band composers have done their own arranging, just like their classical counterparts.

As profession

An orchestrator is a trained musical professional who assigns instruments to an orchestra or other musical ensemble from a piece of music written by a composer, or who adapts music composed for another medium for an orchestra. Orchestrators may work for musical theatre productions, film production companies or recording studios. Some orchestrators teach at colleges, conservatories or universities. The training done by orchestrators varies. Most have completed formal postsecondary education in music, such as a Bachelor of Music (B.Mus.), Master of Music (M.Mus.) or an artist's diploma. Orchestrators who teach at universities, colleges and conservatories may be required to hold a master's degree or a Doctorate (the latter may be a Ph.D. or a D.M.A). Orchestrators who work for film companies, musical theatre companies and other organizations may be hired solely based on their orchestration experience, even if they do not hold academic credentials. In the 2010s, as the percentage of faculty holding terminal degrees and/or Doctoral degrees is part of how an institution is rated, this is causing an increasing number of postsecondary institutions to require terminal and/or Doctoral degrees.

In practice

The term orchestration in its specific sense refers to the way instruments are used to portray any musical aspect such as melody, harmony or rhythm. For example, a C major chord is made up of the notes C, E, and G. If the notes are held out the entire duration of a measure, the composer or orchestrator will have to decide what instrument(s) play this chord and in what register. Some instruments, including woodwinds and brass are monophonic and can only play one note of the chord at a time. However, in a full orchestra there are more than one of these instruments, so the composer may choose to outline the chord in its basic form with a group of clarinets or trumpets (with separate instruments each being given one of the three notes of the chord). Other instruments, including the strings, piano, harp, and pitched percussion are polyphonic and may play more than one note at a time. As such, if the orchestrator wishes to have the strings play the C major chord, they could assign the low C to the cellos and basses, the G to the violas, and then a high E to the second violins and an E an octave higher to the first violins. If the orchestrator wishes the chord to be played only by the first and second violins, they could give the second violins a low C and give the first violins a double stop of the notes G (an open string) and E.

Additionally in orchestration, notes may be placed into another register (such as transposed down for the basses), doubled (both in the same and different octaves), and altered with various levels of dynamics. The choice of instruments, registers, and dynamics affect the overall tone color. If the C major chord was orchestrated for the trumpets and trombones playing fortissimo in their upper registers, it would sound very bright; but if the same chord was orchestrated for the cellos and double basses playing sul tasto, doubled by the bassoons and bass clarinet, it might sound heavy and dark.

Note that although the above example discussed orchestrating a chord, a melody or even a single note may be orchestrated in this fashion. Also note that in this specific sense of the word, orchestration is not necessarily limited to an orchestra, as a composer may orchestrate this same C major chord for, say, a woodwind quintet, a string quartet or a concert band. Each different ensemble would enable the orchestrator/composer to create different tone "colours" and timbres.

A melody is also orchestrated. The composer or orchestrator may think of a melody in their head, or while playing the piano or organ. Once they have thought of a melody, they have to decide which instrument (or instruments) will play the melody. One widely used approach for a melody is to assign it to the first violins. When the first violins play a melody, the composer can have the second violins double the melody an octave below, or have the second violins play a harmony part (often in thirds and sixths). Sometimes, for a forceful effect, a composer will indicate in the score that all of the strings (violins, violas, cellos, and double basses) will play the melody in unison, at the same time. Typically, even though the instruments are playing the same note names, the violins will play very high-register notes, the violas and cellos will play lower-register notes, and the double basses will play the deepest, lowest pitches.

As well, the woodwinds and brass instruments can effectively carry a melody, depending on the effect the orchestrator desires. The trumpets can perform a melody in a powerful, high register. Alternatively, if the trombones play a melody, the pitch will likely be lower than the trumpet, and the tone will be heavier, which may change the musical effect that is created. While the cellos are often given an accompaniment role in orchestration, there are notable cases where the cellos have been assigned the melody. In even more rare cases, the double bass section (or principal bass) may be given a melody, like, the high-register double bass solo in Prokofiev's Lieutenant Kije Suite.

While assigning a melody to a particular section, such as the string section or the woodwinds will work well, as the stringed instruments and all the woodwinds blend together well, some orchestrators give the melody to one section and then have the melody doubled by a different section or an instrument from a different section. For example, a melody played by the first violins could be doubled by the glockenspiel, which would add a sparkling, chime-like colour to the melody. Alternatively, a melody played by the piccolos could be doubled by the celesta, which would add a bright tone to the sound.

In the 20th and 21st century, contemporary composers began to incorporate electric and electronic instruments into the orchestra, such as the electric guitar played through a guitar amplifier, the electric bass played through a bass amplifier, the Theremin and the synthesizer. The addition of these new instruments gave orchestrators new options for creating tonal colours in their orchestration. For example, in the late 20th century and onwards, an orchestrator could have a melody played by the first violins doubled by a futuristic-sounding synthesizer or a theremin to create an unusual effect.

Orchestral instrumentation is denoted by an abbreviated formulaic convention,[3] as follows: flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, trumpet, trombone, tuba. More details can be contained in brackets. A dot separates one player from another, a slash indicates doubling. Timpani and percussion are denoted 2Tmp+ number of percussion.

For example, 3[1.2.3/pic] 2[1.Eh] 3[1.2.3/Ebcl/bcl] 3[1.2/cbn.cbn] tmp+2 is interpreted as:

- 3 flautists, the 3rd doubling on piccolo ("doubling" means that the performer can play flute and piccolo)

- 2 oboists, the 2nd playing English horn throughout

- 3 clarinetists, the 3rd doubling also on E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet

- 3 bassoonists, the 2nd doubling on contrabassoon, the 3rd playing only contra

- Timpani+ 2 percussion.

As an example, Mahler Symphony 2 is scored: 4[1/pic.2/pic.3/pic.4/pic] 4[1.2.3/Eh.4/Eh] 5[1.2.3/bcl.4/Ebcl2.Ebcl] 4[1.2.3.4/cbn]- 10 8 4 1- 2tmp+4-2 hp- org- str.

Examples from the repertoire

J.S Bach

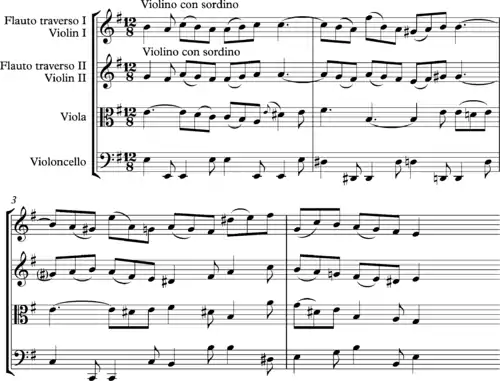

During the Baroque era, composers showed increasing awareness of the expressive potential of orchestration. While some early Baroque pieces have no indication of which instruments should play the piece, the choice of instruments being left to the musical group's leader or concertmaster, there are Baroque works which specify certain instruments. The orchestral accompaniment to the aria 'et misericordia' from J. S. Bach's Magnificat, BWV 243 (1723) features muted strings doubled by flutes, a subtle combination of mellow instrumental timbres.

A particularly imaginative example of Bach's use of changing instrumental colour between orchestral groups can be found in his Cantata BWV 67, Halt im Gedächtnis Jesum Christ. In the dramatic fourth movement, Jesus is depicted as quelling his disciples’ anxiety (illustrated by agitated strings) by uttering Friede sei mit euch ("Peace be unto you"). The strings dovetail with sustained chords on woodwind to accompany the solo singer, an effect John Eliot Gardiner likens to "a cinematic dissolve."[4]

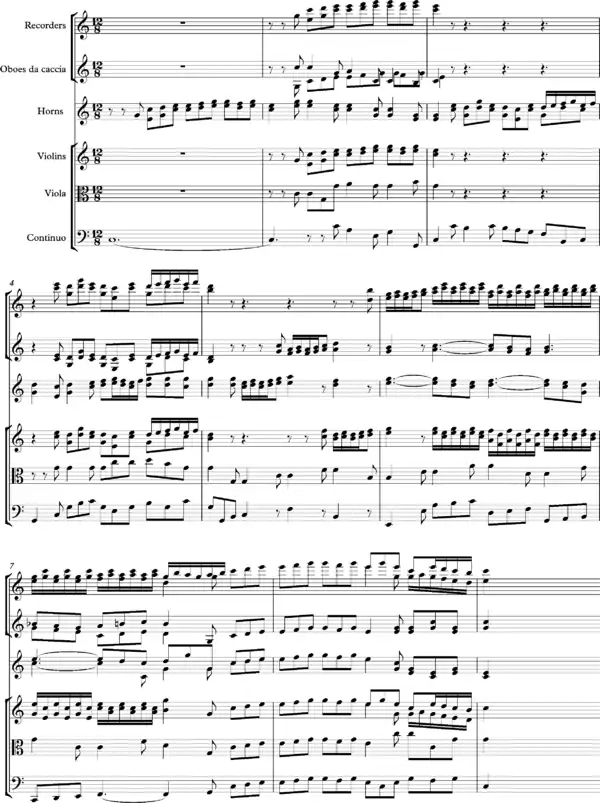

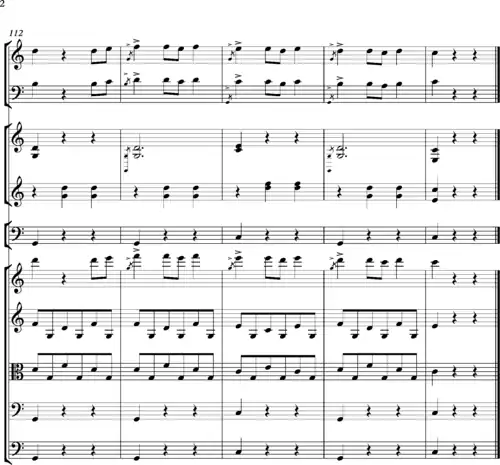

The orchestral introduction to the opening chorus of J. S. Bach's epiphany Cantata Sie werden aus Saba alle kommen BWV 65, which John Eliot Gardiner (2013, p. 328) describes as "one of the crowning glories of Bach’s first Christmas season" further demonstrates the composer's mastery of his craft. Within a space of eight bars, we hear recorders, oboes da caccia, horns and strings creating a "glittery sheen" of contrasted timbres, sonorities and textures ranging from just two horns against a string pedal point in the first bar to a "restatement of the octave unison theme, this time by all the voices and instruments spread over five octaves" in bars 7-8:[5]

Igor Stravinsky (1959, p45) marvelled at Bach's skill as an orchestrator: "What incomparable instrumental writing is Bach's. You can smell the resin [(rosin)] in his violin parts, [and] taste the reeds in the oboes."[6]

Rameau

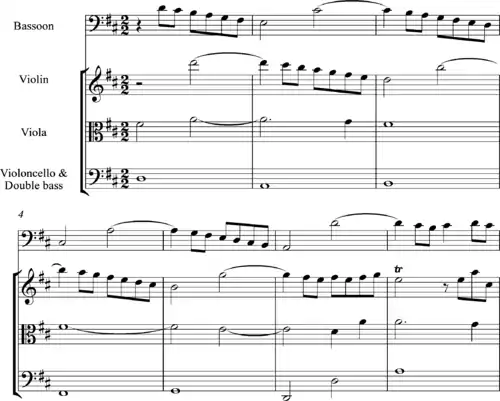

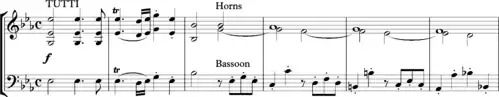

Jean Philippe Rameau was famous for "the eloquence of [his] orchestral writing which was something entirely new... - with a feeling for colour [(i.e., tone colour or timbre)] that is altogether 'modern'."[7] In 'The Entrance of Polymnie' from his opera Les Boréades (1763), the predominant string texture is shot through with descending scale figures on the bassoon, creating an exquisite blend of timbres:

In the aria ‘Rossignols amoureux’ from his opera Hippolyte et Aricie, Rameau evokes the sound of lovelorn nightingales by means of two flutes blending with a solo violin, while the rest of the violins play sustained notes in the background.

Haydn

Joseph Haydn was a pioneer of symphonic form, but he was also a pioneer of orchestration. In the minuet of Symphony No. 97, "we can see why Rimsky-Korsakov declared Haydn to be the greatest of all masters of orchestration. The oom-pah-pah of a German dance band is rendered with the utmost refinement, amazingly by kettledrums and trumpets pianissimo, and the rustic glissando… is given a finicky elegance by the grace notes in the horns as well as by the doubling of the melody an octave higher with the solo violin. These details are not intended to blend, but to be set in relief; they are individually exquisite."[8]

Another example of Haydn's imagination and ingenuity that shows how well he understood how orchestration can support harmony may be found in the concluding bars of the second movement of his Symphony No. 94 (the "Surprise Symphony.") Here, the oboes and bassoons take over the theme, while sustained chords in the strings accompany it with "soft, but very dissonant harmony. "[9] Flute, Horns and timpani add to the mix, all contributing to the "air of uncanny poignancy" that characterises this atmospheric conclusion.[10]

Mozart

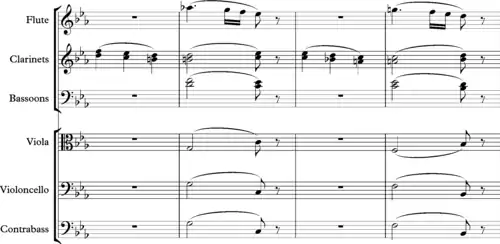

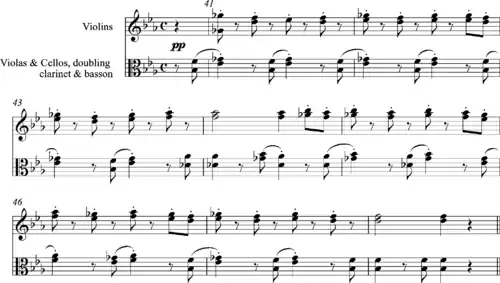

Mozart "was acutely sensitive to matters of instrumentation and instrumental effect where orchestral writing was concerned", including a "meticulous attitude towards the spacing of chords."[11] H. C. Robbins Landon marvels at the "gorgeous wash of colour displayed in Mozart’s scores."[12] For example, the opening movement of the Symphony No. 39 (K543) contains "a charming dialogue between strings and woodwind"[13] that demonstrates the composer's exquisite aural imagination for the blending and contrast of timbres. Bars 102-3 feature a widely spaced voicing over a range of four octaves. The first and second violins weave curly parallel melodic lines, a tenth apart, underpinned by a pedal point in the double basses and a sustained octave in the horns. Wind instruments respond in bars 104–5, accompanied by a spidery ascending chromatic line in the cellos.

A graceful continuation to this features clarinets and bassoons with the lower strings supplying the bass notes.

Next, a phrase for strings alone blends pizzicato cellos and basses with bowed violins and violas, playing mostly in thirds:

The woodwind repeat these four bars with the violins adding a counter-melody against the cellos and basses playing arco. The violas add crucial harmonic colouring here with their D flat in bar 115. In 1792, an early listener marvelled at the dazzling orchestration of this movement "ineffably grand and rich in ideas, with striking variety in almost all obbligato parts."[14]

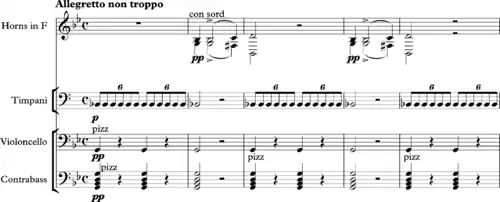

"The main feature in [his] orchestration is Mozart’s density, which is of course part of his density of thought."[15] Another important technique of Mozart's orchestration was antiphony, the "call and response" exchange of musical motifs or "ideas" between different groups in the orchestra. In an antiphonal section, the composer may have one group of instruments introduce a melodic idea (e.g., the first violins), and then have the woodwinds "answer" by restating this melodic idea, often with some type of variation. In the trio section of the minuet from his Symphony No. 41 (1788), the flute, bassoons and horn exchange phrases with the strings, with the first violin line doubled at the octave by the first oboe:

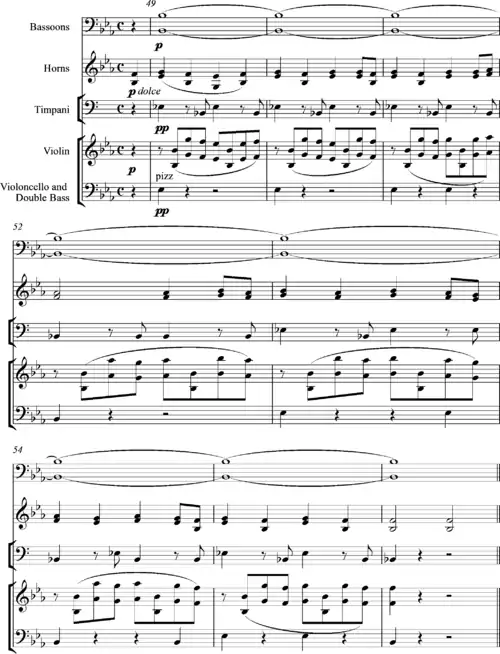

Charles Rosen (1971, p. 240) admires Mozart's skill in orchestrating his piano concertos, particularly the Concerto in E flat major, K482, a work that introduced clarinets into the mix. "This concerto places the greatest musical reliance on tone colour, which is, indeed, almost always ravishing. One lovely example of its sonorities comes near the beginning."[16]

The orchestral tutti in the first two bars is answered by just horns and bassoon in bars 2–6. This passage repeats with fresh orchestration:

"Here we have the unusual sound on the violins providing the bass for the solo clarinets. The simplicity of the sequence concentrates all our interest on tone-colour, and what follows – a series of woodwind solos – keeps it there. The orchestration throughout, in fact, has a greater variety than Mozart had wished or needed before, and fits the brilliance, charm, and grace of the first movement and the finale."[17]

Beethoven

Beethoven's innovative mastery of orchestration and his awareness of the effect of highlighting, contrasting and blending distinct instrumental colours are well exemplified in the Scherzo of his Symphony No. 2. George Grove asks us to note "the sudden contrasts both in amount and quality of sound… we have first the full orchestra, then a single violin, then two horns, then two violins, then the full orchestra again, all within the space of half-a-dozen bars."[18] "The scoring, a bar of this followed by a bar of that, is virtually unique, and one can visualize chaos reigning at the first rehearsal when many a player must have been caught unprepared."[19]

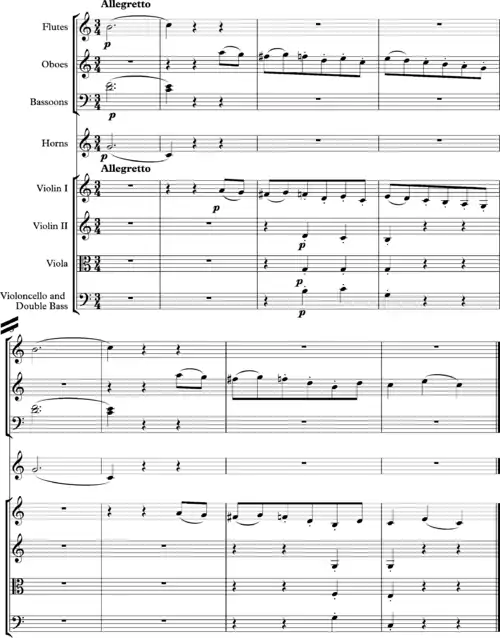

Another demonstration of Beethoven's consummate skill at obtaining the maximum variety out of seemingly unprepossessing and fairly simple material can be found in the first movement of the Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat (‘The Emperor’) Opus 73 (1810). The second subject of the sonata form is a deceptively simple tune that, according to Fiske (1970, p. 41) "is limited to notes playable on the horns for which it must have been specially designed."[20] This theme appears in five different orchestrations throughout the movement, with changes of mode (major to minor), dynamics (forte to pianissimo) and a blending of instrumental colour that ranges from boldly stated tutti passages to the most subtle and differentiated episodes, where instrumental sounds are combined often in quite unexpected ways:

.png.webp)

The theme first appears in the minor mode during the orchestral introduction, performed using staccato articulation and orchestrated in the most delicate and enchanting colours:

This is followed by a more straightforward version in the major key, with horns accompanied by strings. The theme is now played legato by the horns, accompanied by a sustained pedal point in the bassoons. The violins simultaneously play an elaborated version of the theme. (See also heterophony.) The timpani and pizzicato lower strings add further colour to this variegated palette of sounds. "Considering that the notes are virtually the same the difference in effect is extraordinary":[21]

When the solo piano enters, its right hand plays a variant of the minor version of the theme in a triplet rhythm, with the backing of pizzicato (plucked) strings on the off-beats:

This is followed by a bold tutti statement of the theme, "with the whole orchestra thumping it out in aggressive semi-staccato.[22]

:

The minor version of the theme also appears in the cadenza, played staccato by the solo piano:

This is followed, finally, by a restatement of the major key version, featuring horns playing legato, accompanied by pizzicato strings and filigree arpeggio figuration in the solo piano:

Fiske (1970) says that Beethoven shows "a superb flood of invention" through these varied treatments. "The variety of moods this theme can convey is without limit."[23]

Berlioz

The most significant orchestral innovator of the early 19th century was Hector Berlioz. (The composer was also the author of a Treatise on Instrumentation.) "He was drawn to the orchestra as his chosen medium by instinct … and by finding out the exact capabilities and timbres of individual instruments, and it was on this raw material that his imagination worked to produce countless new sonorities, very striking when considered as a totality, crucially instructive for later composers, and nearly all exactly tailored to their dramatic or expressive purpose."[24] Numerous examples of Berlioz's orchestral wizardry and his penchant for conjuring extraordinary sonorities can be found in his Symphonie fantastique. The opening of the fourth movement, entitled "March to the Scaffold" features what for the time (1830) must have seemed a bizarre mix of sounds. The timpani and the double basses play thick chords against the snarling muted brass:

"Although he derives from Beethoven, Berlioz uses features that run counter to the rules of composition in general, such as the chords in close position in the low register of the double basses."[25]

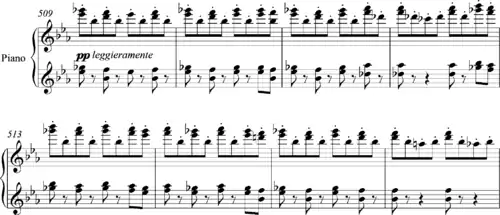

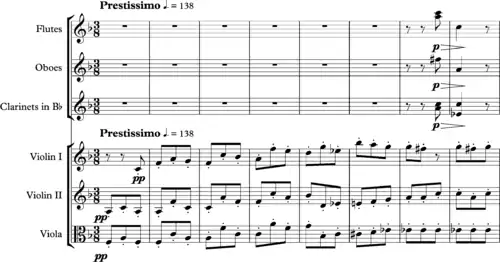

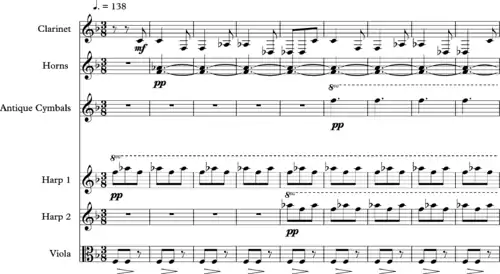

Berlioz was also capable of conveying great delicacy in his instrumental writing. A particularly spectacular instance is the "Queen Mab" scherzo from the Romeo et Juliette symphony, which Hugh Macdonald (1969, p51) describes as "Berlioz’s supreme exercise in light orchestral texture, a brilliant, gossamer fabric, prestissimo and pianissimo almost without pause:

Boulez points out that the very fast tempo must have made unprecedented demands on conductors and orchestras of the time (1830), "Because of the rapid and precise rhythms, the staccatos which must be even and regular in all registers, because of the isolated notes that occur right at the end of the bar on the third quaver…all of which must fall into place with absolutely perfect precision."[26]

Macdonald highlights the passage towards the end of the scherzo where "The sounds become more ethereal and fairylike, low clarinet, high harps and the bell-like antique cymbals…The pace and fascination of the movement are irresistible; it is some of the most ethereally brilliant music ever penned."[27]

The New Grove Dictionary says that for Berlioz, orchestration "was intrinsic to composition, not something applied to finished music...in his hands timbre became something that could be used in free combinations, as an artist might use his palette, without bowing to the demands of line, and this leads to the rich orchestral resource of Debussy and Ravel."[28]

Wagner

After Berlioz, Richard Wagner was the major pioneer in the development of orchestration during the 19th century. Pierre Boulez speaks of the "sheer richness of Wagner’s orchestration and his irrepressible instinct for innovation."[29] Peter Latham says that Wagner had a "unique appreciation of the possibilities for colour inherent in the instruments at his disposal, and it was this that guided him both in his selection of new recruits for the orchestral family and in his treatment of its established members. The well-known division of that family into strings, woodwind, and brass, with percussion as required, he inherited from the great classical symphonists such changes as he made were in the direction of splitting up these groups still further." Latham gives as an example, the sonority of the opening of the opera Lohengrin, where "the ethereal quality of the music" is due to the violins being "divided up into four, five, or even eight parts instead of the customary two."[30]

"The A major chord with which the Lohengrin Prelude begins, in the high register, using harmonics and held for a long time, lets us take in all its detail. It is undoubtedly an A major chord, but it is also high strings, harmonics, long notes – which gives it all its expressivity, but an expressivity in which the acoustic features play a central role, as we have still heard neither melody nor harmonic progression."[31] As he matured as a composer, particularly through his experience of composing The Ring Wagner made "increasing use of the contrast between pure and mixed colours, bringing to a fine point the art of transition from one field of sonority to another."[32] For example, in the evocative "Fire Music" that concludes Die Walküre, "the multiple arpeggiations of the wind chords and the contrary motion in the strings create an oscillation of tone-colours almost literally matching the visual flickering of the flames."[33]

Robert Craft found Wagner's final opera Parsifal to be a work where "Wagner’s powers are at their pinnacle… The orchestral blends and separations are without precedent."[34] Craft cites the intricate orchestration of the single line of melody that opens the opera:

"Parsifal makes entirely new uses of orchestral colour… Without the help of the score, even a very sensitive ear cannot distinguish the instruments playing the unison beginning of the Prelude. The violins are halved, then doubled by the cellos, a clarinet, and a bassoon, as well as, for the peak of the phrase, an alto oboe [cor anglais]. The full novelty of this colour change with the oboe, both as intensity and as timbre, can be appreciated only after the theme is repeated in harmony and in one of the most gorgeous orchestrations of even Wagner’s Technicolor imagination."[35]

Later, during the opening scene of the first act of Parsifal, Wagner offsets the bold brass with gentler strings, showing that the same musical material feels very different when passed between contrasting families of instruments:

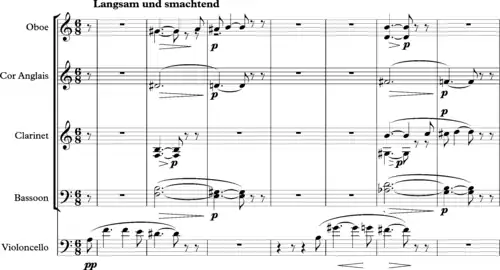

On the other hand, the prelude to the opera Tristan and Isolde exemplifies the variety that Wagner could extract through combining instruments from different orchestral families with his precise markings of dynamics and articulation. In the opening phrase, the cellos are supported by wind instruments:

When this idea returns towards the end of the prelude, the instrumental colors are varied subtly, with sounds that were new to the 19th century orchestra, such as the cor anglais and the bass clarinet. These, together with the ominous rumbling of the timpani effectively convey the brooding atmosphere:

"It’s impressive to see how Wagner… produces balance in his works. He is true genius in this respect, undeniably so, even down to the working out of the exact number of instruments." Boulez is "fascinated by the precision with which Wagner gauges orchestral balance, [which] … contains a multiplicity of details that he achieved with astonishing precision."[36] According to Roger Scruton, "Seldom since Bach's inspired use of obbligato parts in his cantatas have the instruments of the orchestra been so meticulously and lovingly adapted to their expressive role by Wagner in his later operas."[37]

Mahler

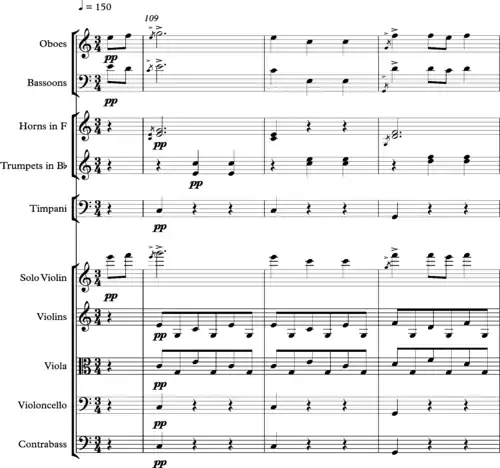

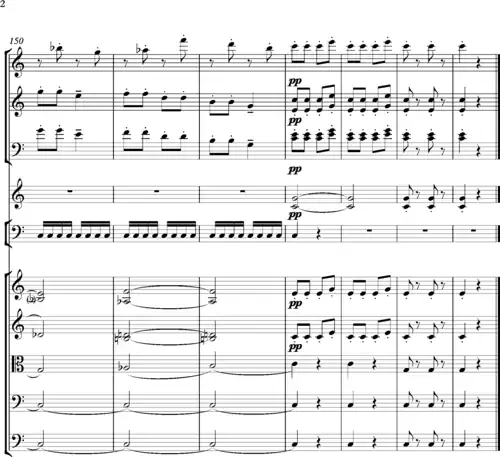

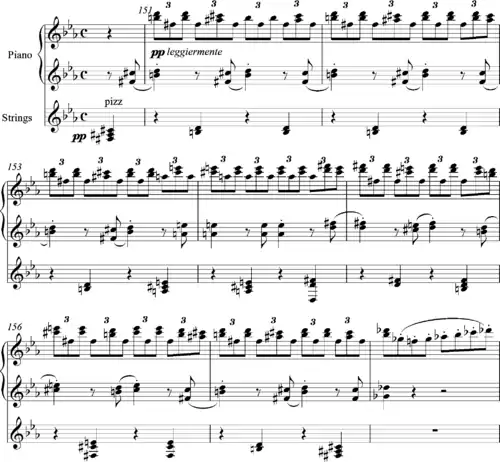

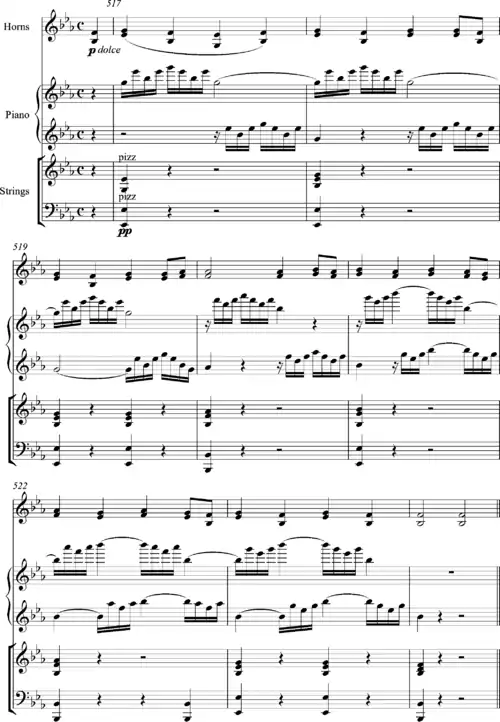

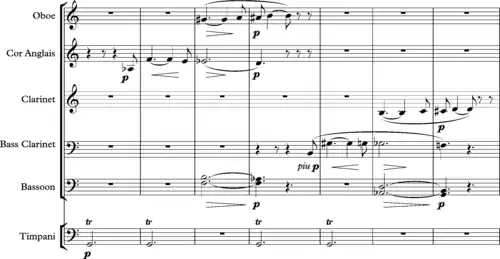

William Austin (1966) says "Mahler expanded the orchestra, going ahead to a historic climax in the direction already marked by Beethoven, Berlioz and Wagner… The purpose of this famous expansion was not a sheer increase in volume, but a greater variety of sound with more nearly continuous gradations… Mahler only occasionally required all his vast orchestra to play together, and his music was as often soft as loud. Its colours were continually shifting, blending or contrasting with each other."[38] Adorno (1971) similarly describes Mahler's symphonic writing as characterised by "massive tutti effects" contrasted with "chamber-music procedures".[39] The following passage from the first movement of his Symphony No. 4 illustrates this:

Only in the first bar of the above is there a full ensemble. The remaining bars feature highly differentiated small groups of instruments. Mahler's experienced conductor's ear led him to write detailed performance markings in his scores, including carefully calibrated dynamics. For example, in bar 2 above, the low harp note is marked forte, the clarinets, mezzo-forte and the horns piano. Austin (1966) says that "Mahler cared about the finest nuances of loudness and tempo and worked tirelessly to fix these details in his scores."[40] Mahler's imagination for sonority is exemplified in the closing bars of the slow movement of the Fourth Symphony, where there occurs what Walter Piston (1969, p. 140) describes as "an instance of inspired orchestration… To be noted are the sudden change of mode in the harmonic progression, the unusual spacing of the chord in measure 5, and the placing of the perfect fourth in the two flutes. The effect is quite unexpected and magical."[41]

According to Donald Mitchell, the "rational basis" of Mahler's orchestration was "to enable us to comprehend his music by hearing precisely what was going on."[42]

Debussy

Apart from Mahler and Richard Strauss, the major innovator in orchestration during the closing years of the nineteenth and the first decades of the twentieth century was Claude Debussy. According to Pierre Boulez (1975, p20) "Debussy’s orchestration… when compared with even such brilliant contemporaries as Strauss and Mahler… shows an infinitely fresher imagination." Boulez said that Debussy's orchestration was "conceived from quite a different point of view; the number of instruments, their balance, the order in which they are used, their use itself, produces a different climate." Apart from the early impact of Wagner, Debussy was also fascinated by music from Asia that according to Austin "he heard repeatedly and admired intensely at the Paris World exhibition of 1889".[43]

Both influences inform Debussy's first major orchestral work, Prelude a l’après-midi d’un faune (1894). Wagner's influence can be heard in the strategic use of silence, the sensitively differentiated orchestration and, above all in the striking half-diminished seventh chord spread between oboes and clarinets, reinforced by a glissando on the harp. Austin (1966, p. 16) continues "Only a composer thoroughly familiar with the Tristan chord could have conceived the beginning of the Faune."[44]

Later in the Faune, Debussy builds a complex texture, where, as Austin says, "Polyphony and orchestration overlap...He adds to all the devices of Mozart, Weber, Berlioz and Wagner the possibilities that he learned from the heterophonic music of the Far East.... The first harp varies the flute parts in almost the same way that the smallest bells of a Javanese gamelan vary the slower basic melody."[45]

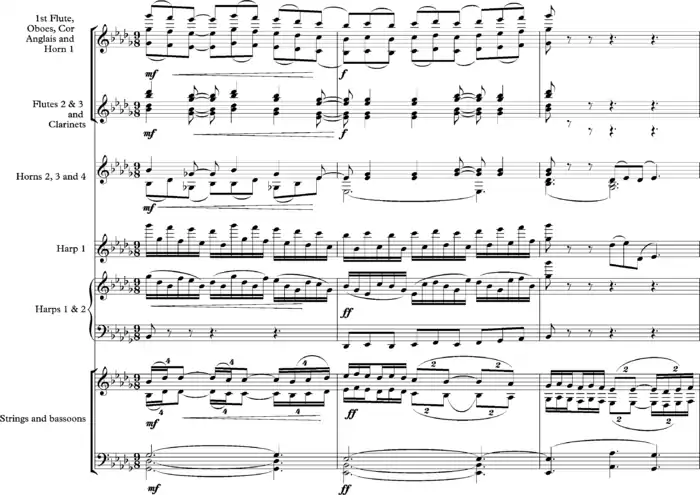

Debussy's final orchestral work, the enigmatic ballet Jeux (1913) was composed nearly 20 years after the Faune. The opening bars feature divided strings, spread over a wide range, a harp doubling horns with the addition of the bell-like celesta in the 5th bar and the sultry voicing of the whole tone chords in the woodwind:

Jensen (2014, p. 228) says "Perhaps the greatest marvel of Jeux is its orchestration. While working on the piano score, Debussy wrote: ‘I am thinking of that orchestral colour which seems to be illuminated from behind, and for which there are such marvellous displays in Parsifal’ The idea, then, was to produce timbre without glare, subdued... but to do so with clarity and precision."[46]

As adaptation

In a more general sense, orchestration also refers to the re-adaptation of existing music into another medium, particularly a full or reduced orchestra. There are two general kinds of adaptation: transcription, which closely follows the original piece, and arrangement, which tends to change significant aspects of the original piece. In terms of adaptation, orchestration applies, strictly speaking, only to writing for orchestra, whereas the term instrumentation applies to instruments used in the texture of the piece. In the study of orchestration – in contradistinction to the practice – the term instrumentation may also refer to consideration of the defining characteristics of individual instruments rather than to the art of combining instruments.

In commercial music, especially musical theatre and film music, independent orchestrators are often used because it is difficult to meet tight deadlines when the same person is required both to compose and to orchestrate. Frequently, when a stage musical is adapted to film, such as Camelot or Fiddler on the Roof, the orchestrations for the film version are notably different from the stage ones. In other cases, such as Evita, they are not, and are simply expanded versions from those used in the stage production.

Most orchestrators often work from a draft (sketch), or short score, that is, a score written on limited number of independent musical staves. Some orchestrators, particularly those writing for the opera or music theatres, prefer to work from a piano vocal score up, since the singers need to start rehearsing a piece long before the whole work is fully completed. That was, for instance, the method of composition of Jules Massenet. In other instances, simple cooperation between various creators is utilized, as when Jonathan Tunick orchestrates Stephen Sondheim's songs, or when orchestration is done from a lead sheet (a simplified music notation for a song which includes just the melody and the chord progression). In the latter case, arranging as well as orchestration will be involved.

Film orchestration

Due to the enormous time constraints of film scoring schedules, most film composers employ orchestrators rather than doing the work themselves, although these orchestrators work under the close supervision of the composer. Some film composers have made the time to orchestrate their own music, including Bernard Herrmann (1911–1975), Georges Delerue (1925–1992), Ennio Morricone (1928–2020), John Williams (born 1932) (his very detailed sketches are 99% orchestrated),[47] Howard Shore (born 1946), James Horner (1953–2015) (on Braveheart), Bruno Coulais (born 1954), Rachel Portman (born 1960), Philippe Rombi (born 1968) and Abel Korzeniowski (born 1972).

Some staff composers at the Walt Disney studios during the 1930's and 1940's (except for Frank Churchill) had orchestrated their own music, such as Paul J. Smith (on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, The Three Caballeros, and Fun and Fancy Free. Leigh Harline (on Snow White and Pinocchio), Oliver Wallace (on Dumbo) and Edward H. Plumb (on Bambi). These composers also developed themes and songs that Churchill had written. Plumb continued to provide numerous film orchestrations at the Disney studios until his death in 1958.

Although there have been hundreds of orchestrators in film over the years, the most prominent film orchestrators for the latter half of the 20th century were Jack Hayes, Herbert W. Spencer, Edward Powell (who worked almost exclusively with Alfred Newman), Arthur Morton, Greig McRitchie, and Alexander Courage. Some of the most in-demand orchestrators today (and of the past 30 years) include Jeff Atmajian, Pete Anthony, Brad Dechter (James Newton Howard, Christopher Young, Theodore Shapiro, Teddy Castellucci, Danny Elfman, John Powell, Marco Beltrami, John Debney, Marc Shaiman, Michael Giacchino, Ludwig Göransson), Conrad Pope (John Williams, Alexandre Desplat, Jerry Goldsmith, James Newton Howard, Alan Silvestri, James Horner, Mark Isham, John Powell, Michael Convertino, Danny Elfman, Howard Shore), Eddie Karam (John Williams, James Horner), Bruce Fowler (Hans Zimmer, Klaus Badelt, Harry Gregson-Williams, Steve Jablonsky, Mark Mancina, John Powell), John Ashton Thomas (John Powell, John Debney, Alan Silvestri, James Newton Howard, Henry Jackman, Lyle Workman, Theodore Shapiro, John Ottman, John Paesano, Alex Heffes, Christophe Beck, Carter Burwell), Robert Elhai (Elliot Goldenthal, Michael Kamen, Ed Shearmur, Brian Tyler, Klaus Badelt, Ilan Eshkeri) and J.A.C. Redford (James Horner, Thomas Newman).

Conrad Salinger was the most prominent orchestrator of MGM musicals from the 1940s to 1962, orchestrating such famous films as Singin' in the Rain, An American in Paris, and Gigi. In the 1950s, film composer John Williams frequently spent time with Salinger informally learning the craft of orchestration. Robert Russell Bennett (George Gershwin, Rodgers and Hammerstein) was one of America's most prolific orchestrators (particularly of Broadway shows) of the 20th century, sometimes scoring over 80 pages a day.

Process

Most films require 30 to 120 minutes of musical score. Each individual piece of music in a film is called a "cue". There are roughly 20-80 cues per film. A dramatic film may require slow and sparse music while an action film may require 80 cues of highly active music. Each cue can range in length from five seconds to more than ten minutes as needed per scene in the film. After the composer is finished composing the cue, this sketch score is delivered to the orchestrator either as hand written or computer generated. Most composers in Hollywood today compose their music using sequencing software (e.g. Digital Performer, Logic Pro, or Cubase). A sketch score can be generated through the use of a MIDI file which is then imported into a music notation program such as Finale or Sibelius. Thus begins the job of the orchestrator.

Every composer works differently and the orchestrator's job is to understand what is required from one composer to the next. If the music is created with sequencing software then the orchestrator is given a MIDI sketch score and a synthesized recording of the cue. The sketch score only contains the musical notes (e.g. eighth notes, quarter notes, etc.) with no phrasing, articulations, or dynamics. The orchestrator studies this synthesized "mockup" recording listening to dynamics and phrasing (just as the composer has played them in). They then accurately try to represent these elements in the orchestra. However some voicings on a synthesizer (synthestration) will not work in the same way when orchestrated for the live orchestra.

The sound samples are often doubled up very prominently and thickly with other sounds in order to get the music to "speak" louder. The orchestrator sometimes changes these synth voicings to traditional orchestral voicings in order to make the music flow better. He may move intervals up or down the octave (or omit them entirely), double certain passages with other instruments in the orchestra, add percussion instruments to provide colour, and add Italian performance marks (e.g. Allegro con brio, Adagio, ritardando, dolce, staccato, etc.). If a composer writes a large action cue, and no woodwinds are used, the orchestrator will often add woodwinds by doubling the brass music up an octave. The orchestra size is determined from the music budget of the film.

The orchestrator is told in advance the number of instruments he has to work with and has to abide by what is available. A big-budget film may be able to afford a Romantic music era-orchestra with over 100 musicians. In contrast, a low-budget independent film may only be able to afford a 20 performer chamber orchestra or a jazz quartet. Sometimes a composer will write a three-part chord for three flutes, although only two flutes have been hired. The orchestrator decides where to put the third note. For example, the orchestrator could have the clarinet (a woodwind that blends well with flute) play the third note. After the orchestrated cue is complete it is delivered to the copying house (generally by placing it on a computer server) so that each instrument of the orchestra can be electronically extracted, printed, and delivered to the scoring stage.

The major film composers in Hollywood each have a lead orchestrator. Generally the lead orchestrator attempts to orchestrate as much of the music as possible if time allows. If the schedule is too demanding, a team of orchestrators (ranging from two to eight) will work on a film. The lead orchestrator decides on the assignment of cues to other orchestrators on the team. Most films can be orchestrated in one to two weeks with a team of five orchestrators. New orchestrators trying to obtain work will often approach a film composer asking to be hired. They are generally referred to the lead orchestrator for consideration. At the scoring stage the orchestrator will often assist the composer in the recording booth giving suggestions on how to improve the performance, the music, or the recording. If the composer is conducting, sometimes the orchestrator will remain in the recording booth to assist as a producer. Sometimes the roles are reversed with the orchestrator conducting and the composer producing from the booth.

Texts

- Michael Praetorius (1619): Syntagma Musicum volume two, De Organographia.

- Valentin Roeser (1764): Essai de l'instruction à l'usage de ceux, qui composent pour la clarinet et le cor.

- Hector Berlioz (1844), revised in 1905 by Richard Strauss: Grand traité d’instrumentation et d’orchestration modernes (Treatise on Instrumentation).

- François-Auguste Gevaert (1863): Traité general d’instrumentation.

- Charles-Marie Widor (1904) : Technique de l’orchestre moderne (Manual of Practical Instrumentation).

- Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov (1912): Основы оркестровки (Principles of Orchestration).

- Cecil Forsyth (1914; 1935): Orchestration. This remains a classic work[48] although the ranges and keys of some brass instruments are obsolete[49]

- Alfredo Casella: (1950) La Tecnica dell'Orchestra Contemporanea.

- Charles Koechlin (1954–9): Traité de l'Orchestration (4 vols).

- Walter Piston (1955): Orchestration.

- Henry Mancini (1962): Sounds and Scores: A Practical Guide to Professional Orchestration.

- Stephen Douglas Burton (1982): Orchestration.

- Samuel Adler (1982, 1989, 2002, 2016): The Study of Orchestration.[50]

- Kent Kennan & Donald Grantham: (1st ed. 1983) The Technique of Orchestration. A 6th edition (2002) is available.[51]

- Nelson Riddle (1985): Arranged by Nelson Riddle

- Perone, James E. (1996). Orchestration Theory: A Bibliography. Music reference collection, Number 52. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29596-4.

- Alfred Blatter (1997) : Instrumentation and Orchestration (Second edition).

See also

References

- "Pictures at an Exhibition | work by Mussorgsky | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- "Sonata for Strings (transcription ... | Details". AllMusic. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- Daniels, David (2005). Orchestral Music a Handbook. Scarecrow Press Inc.

- Gardiner, J.E. (2013, p. 313) Music in the Castle of Heaven; a Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach. London, Allen Lane.

- Gardiner, J.E. (2013, p. 328) Music in the Castle of Heaven. London, Allen Lane.

- Stravinsky I. and Craft, R. Conversations with Igor Stravinsky. London, Faber.

- Pincherle, M. (1967, p. 122) An Illustrated History of Music. London, MacMillan.

- Rosen, C. (1971, pp. 342–3) The Classical Style. London, Faber.

- Taruskin, R. (2010, p. 573) The Oxford History of Western Music: Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Oxford University Press.

- Taruskin, R. (2010, p. 573) The Oxford History of Western Music: Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Oxford University Press.

- Keefe, S.P. (2003, p. 92) The Cambridge Companion to Mozart. Cambridge University Press.

- Robbins Landon, H. (1989, p. 137), Mozart, the Golden Years. London, Thames and Hudson.

- Robbins Landon, H. and Mitchell, D. (1956, p. 191) The Mozart Companion. London, Faber.

- Black, David. "A personal response to the Mozart memorial concert in Hamburg and the Symphony in E-flat (K. 543)". Mozart: New Documents, edited by Dexter Edge and David Black. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- Robbins Landon, H. (1989, p. 137), Mozart, the Golden Years. London, Thames and Hudson.

- Rosen, C. (1971, p. 240) The Classical Style. London Faber.

- Rosen, C. (1971, p. 240) The Classical Style. London Faber.

- Grove, G. (1896, p. 34) Beethoven and his Nine Symphonies. London, Novello.

- Hopkins, A. (1981, p. 51) The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven. London, Heinemann.

- Fiske, R. (1970), Beethoven Concertos and Overtures. London, BBC.

- Fiske, R. (1970, p. 41), Beethoven Concertos and Overtures. London, BBC.

- Fiske, R. (1970, p. 42), Beethoven Concertos and Overtures. London, BBC.

- Fiske, R. (1970, p. 42), Beethoven Concertos and Overtures. London, BBC.

- Macdonald, H. (1969, p. 5) Berlioz Orchestral Music. London, BBC.

- Boulez, P. (203, p. 44) Boulez on Conducting. London, Faber.

- Boulez, P. (203, p. 37) Boulez on Conducting. London, Faber.

- Macdonald, H. (1969, p. 51) Berlioz orchestral Music. London, BBC.

- MacDonald, H., (2001) "Berlioz", article in Sadie, S. (ed.) The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition. London, MacMillan.

- Boulez, P. (1986, p. 273) Orientations. London, Faber.

- Latham, P. (1926) "Wagner: Aesthetics and Orchestration." Gramophone, June 1926.

- Boulez, P. (2005, p. 361) Music Lessons, trans. Dunsby, Goldman and Whittal, 2018. London, Faber.

- Boulez, P. (1986, p. 273) Orientations. London, Faber.

- Boulez, P. (2018, p. 524) Music Lessons, trans. Dunsby, Goldman and Whittal, 2018. London, Faber.

- Craft, R. (1977, p. 82) Current Convictions. London, Secker & Warburg.

- Craft, R. (1977, p. 91) Current Convictions. London, Secker & Warburg.

- Boulez, P. (2003, p. 52) Boulez on Conducting. London, Faber.

- Scruton, R. (2016, p. 147) The Ring of Truth: The Wisdom of Wagner's Ring of the Nibelung. Penguin Random House.

- Austin, W. (1966, p. 123) Music in the 20th Century. London, Dent.

- Adorno, T.W. (1971, p. 53) Mahler, a musical physiognomy. Trans. Jephcott. University of Chicago Press.

- Austin, W. (1966, p. 123) Music in the 20th Century. London, Dent.

- Piston, W. (1969) Orchestration. London, Victor Gollancz.

- Mitchell, D. (1975, p.213) Gustav Mahler, the Wunderhorn Years. London, Faber.

- Austin, W. (1966, p. 20) Music in the 20th century. London, Dent.

- Austin, W. (1966, p. 16) Music in the 20th century. London, Dent.

- Austin, W. (1966, p. 20) Music in the 20th century. London, Dent.

- Jensen, E.F. (2014) Debussy. Oxford University Press.

- "John Williams Orchestration - Gearspace.com". gearspace.com. Retrieved 2022-07-31.

- "Orchestration: Overview". Classical Net. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- Orchestration by Cecil Forsyth - Ebook | Scribd.

- "Adler, Samuel in Oxford Music Online". Archived from the original on 6 September 2012.

- Sealey, Mark. "Book Review: The Technique of Orchestration". Classical Net. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

External links

- Rimsky-Korsakov's Principles of Orchestration at Project Gutenberg – full, searchable text with music images, mp3 files, and MusicXML files

- Rimsky-Korsakov's Principles of Orchestration (full text with "interactive scores")

- The Orchestra: A User's Manual by Andrew Hugill with The Philharmonia Orchestra. In depth information on orchestration including examples and video interviews with instrumentalists of each instrument.

- Books about Music: Orchestration An overview of books on the theory and practice of orchestration.