Government House (Ontario)

Government House was the official residence of the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada and Ontario, Canada. Four buildings were used for this purpose, none of which exist today, making Ontario one of four provinces not to have an official vice-regal residence.[1]

Early accommodations

The colony's first Lieutenant Governor, John Graves Simcoe, occupied a couple of residences during his tenure. Upon his arrival in Upper Canada in 1792, he used one of the buildings at Navy Hall in Niagara-on-the-Lake as a residence,[2] sharing the space with Upper Canada’s legislature.[3] When Simcoe moved the colonial capital to York (present-day Toronto) in 1793, he built a summer residence, Castle Frank, north of the settlement in 1794.[4] Simcoe's successor and the colony's second Lieutenant Governor, Peter Hunter, initially continued to reside in his own home, Russell Abbey, located at the south-west corner of Princess and Front streets.[3]

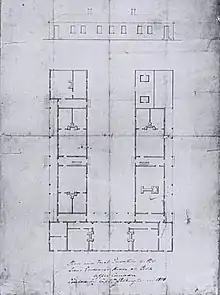

First Government House

The first official government house was a one-storey, U-shaped frame house built at Fort York in 1800, designed by Captain Robert Pilkington and first occupied by Hunter.[5] The structure was destroyed when a nearby powder magazine exploded in 1813 during the War of 1812.[3][6][7][8][9]

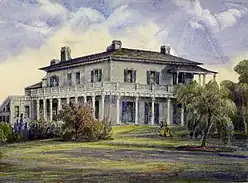

Second Government House (Elmsley House)

After the destruction of the Fort York house, York did not have another Government House until after the War of 1812. In 1815, the government purchased Elmsley House, a more commodious Georgian residence, for its Lieutenant Governor.[10] The new Government House was located in a wooded area to the west of the settled portion of the (then) Town of York, roughly midway on the block now occupied by Roy Thomson Hall and Metro Hall in downtown Toronto.

Built in 1798, the residence had been the home of the Chief Justice and Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, John Elmsley, and it served as the colony's Government House from 1815 to 1841 (and intermittently from 1841 to 1858, during some of the times when Toronto served as the capital of the Province of Canada). From 1847 to 1849 it was home to the Toronto Normal School.

For many years after its purchase by the government, the residence was still known by the name of its former owner, with the correspondence of the Lieutenant Governor typically dated from "Elmsley House".[7][11][12][13] In 1846, the grounds were used for the first annual Provincial Agricultural Fair.[14]

Beginning in 1849, Lord Elgin, the Governor General of the then united Province of Canada, resided for two years at the similarly-named Elmsley Villa, located near what is today the intersection of Bay and Grosvenor Streets (northwest corner), rather than at Elmsley House.[3] Elmsley Villa was a two-storey Georgian structure that stood until at least the 1860s.

Elmsley House was destroyed by fire in 1862.[15]

Third Government House

Four years after the fire at Elmsley House, the firm of Gundry and Langley of Toronto was commissioned to design a new Government House on the same site.[15]

In 1868, construction began on a new Government House, designed in the Second Empire style by architect Henry Langley. A three-storey red brick home, trimmed with Ohio cut stone, the building featured a tower, steeply sloped mansard roofs and dormer windows, with the main entrance and carriage porch facing Simcoe Street. The drawing room on the first floor and the state bedroom on the second floor faced Lake Ontario over a large landscaped garden. Completed in 1870, the house cost CA$105,000, and its first resident was John Beverley Robinson.[15]

By the 20th century, the development of railways and industrial uses nearby prompted the provincial government to seek a more appropriate location for its vice-regal residence, as it had done more than a century before. The third Government House was sold to the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1912 and demolished in 1915.[3][15]

Pendarves (Cumberland House)

During the transition from the third to the fourth Government House, the Lieutenant Governor temporarily lived at Pendarves (later known as Cumberland House) from 1912 to 1915.[3] Originally designed as an Italianate villa by Frederick William Cumberland for his family's use and completed in 1860, the house is located at 33 St. George Street.[16] It has been owned since 1923 by the University of Toronto and now functions as the international students' centre.[17]

Fourth Government House (Chorley Park)

The government sought to construct a new government house on Bloor Street East and 12 architects submitted proposals in 1909.[18] However, as that area was becoming too commercial, the province moved the site to a 0.06 km² (14 acre) parcel of secluded and undeveloped land in Toronto's Rosedale neighbourhood. The proceeds from the sale of the Bloor Street site were used to acquire the land in Rosedale.[19]

Chorley Park, the fourth government house, was constructed between 1911 and 1915. It was named for Chorley, Lancashire, the birthplace of Toronto alderman and first chair of the Toronto Public Library, John Hallam. The house was designed by Francis R. Heakes and built of Credit Valley stone in a French Renaissance style, reminiscent of French châteaux in the Loire Valley. It was one of the most expensive residences ever constructed in Canada at the time and outshone even Rideau Hall in size and grandeur. Sir John Strathearn Hendrie and his wife were the first viceregal couple to live at Chorley Park. The Prince Edward (later King Edward VIII) stayed here for three days in late August 1919, on his cross-Canada tour.

During the Great Depression, Mitchell Hepburn made it a key component of his party's election platform to close Chorley Park, promising that an opulent palace would not be maintained by the taxpayers of Ontario; Chorley Park used 965 tons of coal to operate, whereas the average Toronto home used only six to seven.[20] After Hepburn was appointed premier, following the Liberal Party's victory in the 1937 provincial election, he ensured that Albert Edward Matthews would be the last lieutenant governor of Ontario to live in an official residence; in 1937, after only 22 years and seven viceroys, Chorley Park was closed. The contents of the mansion were auctioned off the following year, bringing in a profit of $18,000,[20] and Ontario became the first province in Canada not to have a government house. (Alberta also closed its Government House in 1938.) The estate was bought by the federal Crown-in-Council and thereafter served various functions, including a military hospital during the Second World War, the headquarters of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Toronto, and a residence for refugees of the 1956 Hungarian uprising, including several of Imre Nagy's staff members.[20]

Under Mayor Nathan Phillips in 1960, the City of Toronto bought the house for $100,000, in order to destroy it and create municipal parkland.[20] At the time, Chorley Park was considered dilapidated and outmoded and municipal funds were being spent demolishing heritage structures throughout the city to make room for modern buildings. The building was demolished in 1961 and the grounds of the estate were added to the civic parks system.

The only trace of Government House left is the bridge to the forecourt and some depressions in the earth that outline the rough footprint of its foundations. The once formal gardens have long gone fallow and, today, Chorley Park is a naturalized parkland.

Current facilities

Ontario's Lieutenant Governor uses an office and suite of rooms for entertainment in the Ontario Legislative Building, and lives in his or her private Toronto home or is provided a rented residence by the provincial government.[3] Since the closure of the last Government House, whenever the Sovereign is visiting Toronto he resides in the Royal Suite at the Fairmont Royal York Hotel.[21]

See also

Footnotes

- The others are Alberta, Saskatchewan and Quebec, although Saskatchewan's Government House does contain the Lieutenant-Governor's offices and is used for official entertaining.

- "Navy Hall". Fort George National Historic Site of Canada. Parks Canada. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- "Previous Government Houses". Lieutenant Governor of Ontario. Archived from the original on 15 September 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- "Castle Frank". Toronto Plaques. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- "GALLERY 1793–1815".

- Arthur, Eric. Toronto, No Mean City. University of Toronto Press, 1986. Page 20. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- http://www.toronto.ca/culture/brochures/fortyyork_report_low.pdf Fort York and Garrison Common: Parks and Open Space Design and Implementation Plan. City of Toronto, 2001. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- Clement, Bronwyn. "Fort York Dig: Scraping back the layers". Spacing Toronto. Spacing. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- "PILKINGTON, ROBERT". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 101: Elmsley House". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Revisited.

- The History of These Graves Archived 2009-12-13 at the Wayback Machine. Friends of Fort York. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- Henry Scadding (1878). "Toronto of Old: Collections and Recollections Illustrative of the Early Settlement and Social Life of the Capital of Ontario". Willing & Williamson. p. 90. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- Toronto Then and Now. Toronto Public Library. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- "Early CNE".

- Roy Thomson Hall. Lost Rivers. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- Pendarves – Cumberland House

- Centre for International Experience

- "Perspective View from South West Point, Competitive Design (awarded 2nd Prize) of Architect George W. Gouinlock for new Ontario Government House". Construction (Toronto). 4 (6): 55–56. May 1911.

- Chorley Park. Lost Rivers. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- Maloney, Mark; Toronto Star: The Curious Case of Chorley Park; July 30, 2007

- Connor, Kevin (April 21, 2016). "An inside look at the Queen's Royal York suite". Toronto Sun. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

.jpg.webp)