Christ and Satan

Christ and Satan is an anonymous Old English religious poem consisting of 729 lines of alliterative verse, contained in the Junius Manuscript.

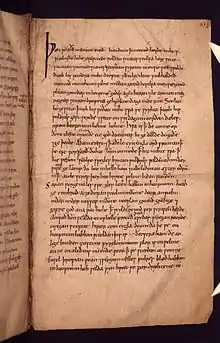

Junius Manuscript

The poem is located in a codex of Old English biblical poetry called the Junius Manuscript. The Junius Manuscript consists of two booklets, referred to as Book I and Book II, and it contains an assortment of illustrations. Book I of the Junius Manuscript houses the poems Genesis A, Genesis B, Exodus, and Daniel, while Book II holds Christ and Satan, the last poem in the manuscript.

Authorship

Francis Junius was the first to credit Cædmon, the 7th century Anglo-Saxon religious poet, as the author of the manuscript. Junius was not alone in suggesting that Cædmon was the author of the manuscript, as many others noticed the “book’s collective contents strikingly resembled the body of work ascribed by Bede to the oral poet Cædmon” (Remley 264). However, the inconsistencies between Book I and Book II has made Christ and Satan a crucial part of the debate over the authorship of the manuscript. Most scholars now believe the Junius Manuscript to have been written by multiple authors. One piece of evidence that has called the authorship of the manuscript into question is the fact that unlike Genesis A and Genesis B, the complaints of Satan and the fallen angels (in the Book II poem Christ and Satan) are not made against God the Father, but rather Jesus the Son.[1] This variance is just one example of why the authorship of the manuscript is under suspicion. Another cause for suspicion is the opinion that Satan is portrayed “as a much more abject and pathetic figure [in Christ and Satan] than, for example in Genesis B”.[1] Furthermore, a single scribe is responsible for having copied out Genesis, Exodus, and Daniel, but Book II (consisting only of Christ and Satan) was entered “by three different scribes with rounder hands”.[2]

Structure and synopsis

Unlike the poems in Book I of the Junius manuscript, which rely on Old Testament themes, Christ and Satan encompasses all of biblical history, linking both the Old Testament and New Testament, and expounding upon a number of conflicts between Christ and Satan.[1]

The composite and inconsistent nature of the text has been and remains some cause for confusion and debate.[3] Nevertheless, Christ and Satan is usually divided into three narrative sections:

- The Fall of Satan. The first section runs from lines 1 to 365 and consists of the grievances of Satan and his fellow fallen angels. In this section, Satan and his fallen brethren direct their complaints toward Christ the Son. This is an unusual and unparalleled depiction of the story, as the complaints of Satan and the fallen angels are usually directed toward God the Father, as is the case in the preceding poems Genesis A and Genesis B.[1]

- The Harrowing of Hell. The second section runs from lines 366 to 662 and offers an account of the Resurrection, Ascension, and Last Judgment, with emphasis on Christ's Harrowing of Hell and victory over Satan on his own ground.[1]

- The Temptation of Christ. The third and last section runs from lines 663 to 729 and recalls the temptation of Christ by Satan in the desert.[1]

In addition, the poem is interspersed with homiletic passages pleading for a righteous life and the preparation for Judgment Day and the afterlife. The value of the threefold division has not gone uncontested. Scholars such as Donald Scragg have questioned whether Christ and Satan should be read as one poem broken into three sections or many more poems which may or may not be closely interlinked. In some cases, such as in the sequence of Resurrection, Ascension and Day of Judgment, the poem does follow some logical narrative order.[4]

Analysis

Due to the wide variety of topics in the text, scholars debate as to what constitute the main themes. Prevalent topics discussed, however, are 1) Satan as a character; 2) The might and measure of Christ and Satan (Christ vs. Satan: struggle for power) and 3) A search for Christ and Satan's self and identity (Christ vs. Satan: struggle for self).[5]

Satan as a character

Old English authors often shied away from overtly degrading the devil.[6] In comparison, Christ and Satan humiliates, condemns, and de-emphasizes Satan versus Christ, holding him as the epic enemy and glorious angel.[7] The text portrays Satan as a narrative character, giving him long monologues in the "Fall of Satan" and the "Harrowing of Hell", where he is seen as flawed, failing, angry, and confused. In combining another predominant theme (see Christ vs. Satan: Struggle for Identity), Satan confuses and lies about his own self-identity, with his demons lamenting in hell saying,

- “Đuhte þe anum þæt ðu ahtest alles gewald,

- heofnes and eorðan, wære halig god,

- scypend seolfa.” (55-57a)

- “Seeming that you [Satan] alone possessed the power over all, heaven and earth,

- that you were the holy God, yourself the shaper.”

In addition, Christ and Satan is one of the Old English pieces to be included in “The Plaints of Lucifer”.[8] The “Plaints” are pieces where Satan participates in human context and action and is portrayed as flawed, tormented, and ultimately weak, others including Phoenix, Guthlac, and “incidentally” in Andreas, Elene, Christ I and Christ II, Juliana, and in some manners of phraseology in Judith.[9] In comparison with other literature of the time period which portrayed Satan as the epic hero (such as Genesis A and B), the “Plaints” seem to have become much more popular historically, with a large number of plaintive texts surviving today.[10]

Christ vs. Satan: struggle for power

The power struggle between the two key characters in Christ and Satan is emphasized through context, alliteration, and theme; with a heavy emphasis on the great measure (ametan) of God. From the very beginning of the piece, the reader is reminded and expected to know the power and mightiness of God, the creator of the universe:

- “þæt wearð underne eorðbuendum

- Þæt meotod hæfde miht and strengðo

- Ða he gefastnade foldan sceatas” (1-3)

- “It has become manifested to men of earth that the measurer had might

- and strength when he put together the regions of the earth”

In all three parts of Christ and Satan, Christ's might is triumphant against Satan and his demons.[11] Alliteration combines and emphasizes these comparisons. The two words metan "meet" and ametan "measure" play with Satan's measuring of hell and his meeting of Christ,[12] caritas and cupiditas,[13] are compared between Christ and Satan, the micle mihte "great might" of God is mentioned often, and wite "punishment", witan "to know", and witehus "hell"[14] coincide perfectly with Satan's final knowledge that he will be punished to hell (the Fall of Satan). In the Temptation, truth and lies are compared between Christ and Satan explicitly through dialogue and recitation of scripture. Although both characters quote scripture, Christ is victorious in the end with a true knowledge of the word of God. The ending of The Temptation in Christ and Satan deviates from Biblical account. Actual scripture leaves the ending open with the sudden disappearance of Satan (Matthew 4:1-11), but Christ and Satan takes the more fictional and epic approach with a victory for Christ over Satan—adding to what scripture seems to have left to interpretation.

Christ vs. Satan: struggle for self

The word seolf "self" occurs over 22 times in the poem,[15] leaving scholars to speculate about the thematic elements of self-identity within the piece. Satan confuses himself with God and deceives his demons into believing that he is the ultimate Creator, while the seolf of Christ is emphasized many times throughout the piece. In the wilderness (Part III, the Temptation of Christ), Satan attacks Christ by questioning his identity and deity,[16] saying:

- “gif þu swa micle mihte habbe”

- “If you have that much might” (672)

and

- “gif þu seo riht cyning engla and monna

- swa ðu ær myntest” (687-88)

- “If you are the right king of men and angels, as you earlier thought”

Christ finishes triumphantly, however, by banishing Satan to punishment and hell, manifesting his ability to banish the devil and revealing the true identities of himself and Satan.[17]

Influence

The poems of the Junius Manuscript, especially Christ and Satan, can be seen as a precursor to John Milton's 17th century epic poem Paradise Lost. It has been proposed that the poems of the Junius Manuscript served as an influence of inspiration to Milton's epic, but there has never been enough evidence to support such a claim (Rumble 385).

Notes

- Orchard 181.

- Rumble 385.

- For instance, W.D. Conybeare (1787-1857) commented on its fragmentary nature, saying that the poem was "[i]ntroduced by several long harangues of Satan and his angels … so little connected with the sequel or with each other, and so inartificially thrown together, as rather to resemble an accumulation of detached fragments than any regular design." As quoted in Clubb xlii, xliii.

- Scragg 105

- Clubb, Sleeth, Dendle, Wehlau.

- Dendle 41.

- Dendle 41, 69.

- Clubb xxvi and Dendle 40

- Clubb xxvi.

- Dendle 41

- Sleeth 14

- Wehlau 291

- Sleeth 14.

- Wehlau 291-2.

- Wehlau 288

- Wehlau 290.

- Wehlau.

Bibliography

- Editions and translations

- Finnegan, R.E. (ed.). Christ and Satan: A Critical Edition. Waterloo, 1977.

- Krapp, G. (ed.). The Junius Manuscript. The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Record 1. New York, 1931.

- Clubb, Merrel Gare (ed.). Christ and Satan: An Old English Poem. New Haven, CT, 1925. (Reprint: Archon Books, 1972)

- Bradley, S.A.J. (tr.). Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London; David Campbell, 1995. 86-105.

- Kennedy, George W. (tr.). Christ and Satan, The Medieval and Classical Literature Library. 25 October 2007.

- Trott, James H. A Sacrifice of Praise: An Anthology of Christian Poetry in English from Caedmon to the 20th Century. Cumberland House, 1999.

- Foys, Martin et al. (ed. and tr. to digital facsimile). Old English Poetry in Facsimile Project. Center for the History of Print and Digital Culture. Madison, 2019.

- Secondary literature

- Dendle, P.J. Satan Unbound: the Devil in Old English Narrative.

- Liuzza, R.M.

- Lucas, P.J. "On the Incomplete Ending of Daniel and the Addition of Christ and Satan to MS Junius II." Anglia 97 (1979): 46-59.

- Sleeth, Charles R. Studies in Christ and Satan. Toronto Press, 1982.

- Wehlau, Ruth. "The Power of Knowledge and the Location of the Reader in Christ and Satan." JEGP 97 (1998): 1-12.

- Encyclopedia entries:

- Orchard, A.P.M. “Christ and Satan.” Medieval England: An Encyclopedia, ed. Paul E. Szarmach, M. Teresa Tavormina, Joel T. Rosenthal. New York: Garland Pub., 1998. 181.

- Remley, Paul G. “Junius Manuscript.” The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Michael Lapidge. Oxford: Blackwell Pub., 1999. 264-266.

- Rumble, Alexander R. “Junius Manuscript.” Medieval England: An Encyclopedia, ed. Paul E. Szarmach, M. Teresa Tavormina, Joel T. Rosenthal. New York: Garland Pub., 1998. 385-6.

- Scragg, Donald. "Christ and Satan." The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Michael Lapidge. Oxford: Blackwell Pub., 1999. 105.