Christopher Chowne

General Christopher Chowne (1771–15 July 1834), born Christopher Tilson and also known as Christopher Tilson-Chowne, was a British Army officer most notable for his service in the Peninsular War. He joined the army in 1788 and after periods of service in the 23rd Regiment of Foot and an Independent Company, he became lieutenant-colonel of the 99th Regiment of Foot in 1794. The 99th were disbanded in 1797, and Chowne joined instead the 44th Regiment of Foot in 1799. He commanded the regiment at the battles of Abukir and Mandora in the British campaign in Egypt in 1801. In 1805 he was appointed a brigadier-general, as which he served in the Anglo-Russian occupation of Naples later in the year and subsequently in the West Indies.

Christopher Chowne | |

|---|---|

| Birth name | Christopher Tilson |

| Other name(s) | Christopher Tilson-Chowne |

| Born | 1771 |

| Died | 15 July 1834 Eaton Place, Pimlico |

| Service/ | British Army |

| Years of service | 1788–1834 |

| Rank | General |

| Commands held | 99th Regiment of Foot 44th Regiment of Foot 3rd Brigade, Anglo-Portuguese Army 1st Brigade, 2nd Division 2nd Division |

| Battles/wars | |

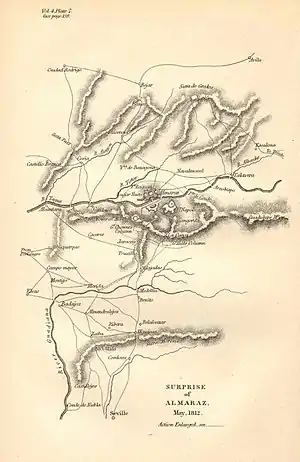

Chowne was promoted to major-general in 1808 and in the following year began serving in the Peninsular War. He commanded a brigade in a column commanded by William Carr Beresford that unsuccessfully attempted to cut off the French army after the Second Battle of Porto, and then resigned his command because of disagreements with Portuguese units in the force. He was then given a brigade in Rowland Hill's 2nd Division with which he fought at the Battle of Talavera and temporarily commanded the division when Hill was injured. He returned to England as a staff officer in 1810 but re-joined the 2nd Division as its acting commanding officer "under Hill" in 1812. He commanded a diversionary column at the Battle of Almaraz but by the end of 1812 had relinquished his command.

Long thought of as an incompetent officer who lacked energy and ability, Chowne was recalled from the Iberian Peninsula for the last time in December 1812 and did not see action again. He was promoted to general in 1830 and died four years later in London.

Early life

Christopher Tilson was born in 1771, the son of the banker John Tilson of Watlington Park and his wife Maria née Lushington.[1][2][3] Watlington Park, situated in Oxfordshire, England, was a large country house that had been rebuilt by the family in around 1755.[4] Tilson had three brothers; John, who became a lieutenant-colonel in the British Army, George, who became a lieutenant in the Royal Navy, and James, who followed his father into banking.[1][5][6] His only sister, Maria, married the Reverend William Marsh.[7]

Military career

Early career

Tilson joined the British Army on 13 February 1788 as a second lieutenant in the 23rd Regiment of Foot.[1][5] He was promoted to lieutenant in the 23rd in 1790 and then became captain of an Independent Company on 25 April 1793.[1] In the following year he was promoted to major in the 99th Regiment of Foot.[5] Tilson was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and given command of the regiment on 15 November of the same year.[8] He was with the regiment in the West Indies during 1796, when the Dutch colonies of Demerara, Essequibo, and Berbice agreed to surrender to the British. Under the command of Major-General John Whyte and with two other regiments, the 99th successfully occupied Demerara and Essequibo on 21 April, and Berbice on 28 April.[9][10] The 99th was disbanded in 1797 and Tilson went on half pay in March 1798.[5][8]

On 24 January 1799 Tilson was given command of the 44th Regiment of Foot which was serving in garrison at Gibraltar; he was then promoted to brevet colonel on 1 January 1800.[5][8][11][12] In October the regiment joined the expedition preparing to fight the British campaign in Egypt, in Major-General Sir John Doyle's 4th Brigade.[5][11] They spent some time ashore at Minorca in November to train and prepare for long cross country marches and then in February 1801 practiced amphibious landings.[13][14] The army landed in Aboukir Bay on 8 March during the Battle of Abukir, with Tilson's regiment 263 men strong.[15]

The 44th then fought at the Battle of Mandora on 13 March where, still heavily understrength, they were ordered to attack two forward-placed French howitzers that were dropping shells behind the hills the army was using as cover. The regiment charged the guns and destroyed them but was then caught in a crossfire by thirty French cannon situated on the Nicopolis heights on their right flank. The French sent out a force to counterattack Tilson's regiment and they were forced to retreat, having had two men killed and a further twenty five men injured, including Tilson.[16][17] The regiment would go on to serve at the Battle of Alexandria on 21 March but a different lieutenant-colonel is recorded as leading the 44th at this time. The campaign ended in September.[5][16][18]

On 25 May 1805 Tilson was appointed a brigadier-general on the staff of the army of Lieutenant-General Sir James Craig that initiated the Anglo-Russian occupation of Naples soon afterwards.[8] The occupation ended in the following year when the advance of a French army of 30,000 men, combined with the defeat at the Battle of Austerlitz, put Craig's force, 8,000 men strong, into an untenable position.[19][20][21][22] They left Naples for Messina on 19 January.[22][23]

Porto campaign

Tilson retained his appointment as brigadier after the occupation and travelled to serve in the West Indies in 1806.[5] He was promoted to major-general on 25 April 1808 and in March 1809 was sent to serve on the staff of the army in the Iberian Peninsula fighting the Peninsular War.[24][25][26] From April he commanded the 3rd Brigade in the army, divisions not having yet been implemented, in a column commanded by Marshal William Carr Beresford.[Note 1][5][28] During the French retreat after the Second Battle of Porto the column manoeuvred through high mountain roads in poor conditions in order to try and cut the path of the enemy retreat at Amarante.[29][30] The bridge at Amarante was guarded by a force commanded by General Louis Henri Loison. The British reached it on 12 May, with a Portuguese force under General Francisco da Silveira Pinto da Fonseca Teixeira having already pushed Loison back over the Douro.[31][32]

In the evening of 12 May Loison left Amarante, leaving the French route of retreat open to Beresford.[Note 2][33] Tilson's brigade then began a chase after the main French army, with Tilson forced to beg food off of his Portuguese allies just to keep his 1,500 man brigade marching, his own supplies having been severely depleted.[29][34] Many of Tilson's men fell behind during the advance, but the majority were able to later re-join the brigade.[35][33] By 17 May the column had reached as far as Chaves but in its exhaustion was unable to go any further, and the French succeeded in escaping.[36]

Battle of Talavera

Later in the month Tilson resigned command of his brigade because he refused to continue to serve alongside the Portuguese soldiers of Beresford's column, having also gained a reputation as an incompetent officer. Tilson was then appointed to command the 1st Brigade of Major-General Rowland Hill's 2nd Division on 23 June, soon after its creation.[Note 3][39][40][41] He commanded the brigade at the Battle of Talavera, where on 27 July Hill's division engaged an attacking column led by General François Amable Ruffin and routed it as it attempted to take the high ground of the Cerro de Medellín on the left, or north, side of the battlefield.[42][43][44] Towards the end of the engagement Hill was wounded in the head and Tilson took over command of the division for the remainder of the day.[45][46]

On the following day the battle continued and Tilson's brigade suffered heavy casualties in the morning from French cannon fire as they stood at their positions on the Cerro de Medellín, one of three brigades stationed there to ensure the hill was not re-taken.[47][48] After forty-five minutes of cannon fire the French advanced to try and re-take the position, with Tilson facing the 24th Line Infantry.[49] The British skirmishers retreated as the 24th advanced up the hill, and Hill then ordered Tilson's brigade and one other to stand and fire into the French, causing great confusion in the ranks of the 24th. A bayonet charge was then called for, but before they could reach the French they had begun retreating back down the Cerro de Medellín.[50] The routing of the 24th exposed the flank of Ruffin's remaining units, and attacks from the King's German Legion pushed the rest of the force back. The French did not attack the Cerro de Medellín again during the battle.[51][52] Tilson was thanked in the dispatches of Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Wellesley and would go on to receive the Army Gold Medal with a clasp for Talavera.[5][42][53]

Tilson was one of only two major-generals in command of a brigade in Wellesley's army at this time, but his incompetency outweighed his seniority.[41] He was replaced in command of his brigade on 15 September, but stayed with the army afterwards.[5][38]

2nd Division and Almaraz

Tilson resigned his position in the army again in July 1810 and returned home to serve as a staff officer; he was appointed a local lieutenant-general to serve again in the peninsula on 11 November 1811.[24][54] Tilson subsequently changed his surname to Chowne on 14 January 1812 in order to satisfy the conditions of an inheritance he had received.[Note 4] He returned to the peninsula on 14 April as the acting commander of the 2nd Division.[42][58][59][17] Chowne's reputation in the army had not improved during his period of leave, and historian Andrew Bamford argues that as an "obvious dud", Chowne was placed in a position where the reliable Hill could oversee and mentor him.[60][61] He commanded the division "under Hill", and because of this was also employed away from his division for periods during this time; however he was present with the division, and Hill, at the Battle of Almaraz.[Note 5][59][63]

Hill commanded 6,000 men split into three columns, with the intention of capturing and destroying a tactically important bridge and the fortresses guarding it at Almaraz.[64] The force left Almendralejo on 12 May and by 16 May they had reached Jaraicejo, to the south of Almaraz, through a series of difficult and mountainous passes.[65] Chowne commanded the left-most of Hill's columns, tasked with making a diversionary attack on the fortress of Mirabete, 4 miles (6.4 km) south-west of the bridge.[Note 6][70] On the night of 17–18 May the three columns began to march towards their target, but only Chowne's column arrived before dawn, and he failed to take advantage of the opportunity to attack Mirabete.[71][72] Early in the morning of 19 May, Chowne made his feint on the castle with a heavy bombardment of 24-pound howitzers and a small attack by some skirmishers, which diverted the attention of the French forces guarding the bridge itself.[73][74][75] Hill simultaneously brought his other two columns down and attacked and captured the fortress that guarded the bridge on their side of the River Tagus. They used the guns of the captured fortress to destroy her consort on the other side of the river along with the bridge, which was made of pontoons.[76] After this, incorrect reports that a French army was mustering nearby reached Hill, and he had his force withdraw, reaching the safety of Merida on 26 May.[77]

Recall and retirement

Chowne relinquished his position within the 2nd Division in November or December 1812 and on 6 December he left the peninsula for the final time when Wellesley, now Lord Wellington, requested his recall from the theatre.[5][42][78] This recall was part of a larger campaign by Wellington to remove his most inept generals from the army, of which Chowne was the last to leave.[79] An air of incompetency had surrounded Chowne since the start of his service in the peninsula, but added to that now was the opinion that he had spent too much of his time on leave in England. Colonel Henry Torrens, the Military Secretary, wrote that:

"the habitual want of energy in his character, and his indifference to his profession, have rendered him a burden to the army"[80]

Chowne's recall was timed so that he was not present with the army on 4 June 1813, when he received his full promotion to lieutenant-general and may have been required to fulfil more important duties than he had previously.[80][58] His foreign service at an end, Chowne was given the colonelcy of the 76th Regiment of Foot on 17 February 1814.[24][58][81] He spent the rest of the war unemployed, making up part of Jane Austen's Drury Lane party in early March.[Note 7][83] At the close of the War of 1812 he was appointed to sit on the court martial of Lieutenant-General Sir George Prevost which was planned for 15 January 1816, but Prevost died on 5 January and the court martial was never held.[84] Chowne was promoted to general in 1830 and died four years later on 15 July 1834, at his house in Eaton Place, Pimlico.[5][85]

Family

While on leave in Exmouth in December 1810, Chowne courted a famous heiress named Esther Acklom, but she reneged on their engagement shortly before the wedding in 1812, at which point he retired to Bath.[Note 8][86] By 1823 he had recovered from this, and he married Jane Craufurd, the daughter of Sir James Gregan-Craufurd, in Brussels on 12 October. They had no children. After Chowne's death his widow married the Reverend Sir Henry Dukinfield in 1836.[1][3][87]

Notes and citations

Notes

- Tilson's brigade consisted of five companies of the 60th Regiment of Foot, the 2nd Battalion of the 87th Regiment of Foot, the 1st Battalion of the 88th Regiment of Foot, and the 1st Battalion of the Portuguese 1st Regiment.[27]

- If Loison had not retreated from Amarante, it was to have been Tilson's brigade who would have attacked him there.[33]

- This brigade consisted of the 1st Battalion of the 3rd Regiment of Foot, the 2nd Battalion of the 48th Regiment of Foot, and the 2nd Battalion of the 66th Regiment of Foot.[37] In September the 2nd Battalion of the 31st Regiment of Foot also joined.[38]

- This was in compliance with the will of Mary, Countess De Brühl, who was a relative of Chowne's.[55][56] His surname is also recorded as Tilson-Chowne.[57] Part of the inheritance was an estate at Alfriston, Sussex.[3]

- Chowne is also recorded as being the "deputy" commander of 2nd Division in this period.[62]

- The original plan had been for Chowne's force to truly take the castle, but the French had reinforced it and the defences were now too much for the small British force to take on. Wellesley would go on to write that he believed that Chowne could have taken the castle if the attack had gone ahead when they arrived on 16 May.[66][67][68] Chowne's column consisted of the 28th Regiment of Foot, 34th Regiment of Foot, and 6th Caçadores.[69]

- Austen did not know Chowne well, but had probably seen him previously when he played Frederick in an amateur performance of the play Lovers' Vows, commenting in 1814 that "he has not much remains of Frederick".[82]

- Acklom went on to instead marry Lord Althorp in 1815 having broken another engagement, this time to a Mr Maddox, before this.[86]

Citations

- Reid (2019), p. 211.

- Glover (2001), p. 198.

- Austen (2011), p. 576.

- Historic England. "Watlington Park (1059422)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- McGuigan, Ron (September 2012). "Tilson, Christopher". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- Austen (2011), pp. 576–577.

- Austen (2011), p. 577.

- Royal Military Calendar (1820), p. 302.

- Howard (2015), pp. 95–96.

- Southey (1827), p. 119.

- Mackesy (2010), p. 15.

- Reid (2019), pp. 211–212.

- Mackesy (2010), p. 34.

- Mackesy (2010), p. 43.

- Mackesy (2010), p. 70.

- Mackesy (2010), pp. 94–95.

- Carter (1887), p. 35.

- Carter (1887), p. 36.

- Flayhart (1992), p. 147.

- Flayhart (1992), p. 153.

- Rosenburg (2017), p. 168.

- Flayhart (1992), p. 155.

- Flayhart (1992), p. 165.

- Royal Military Calendar (1820), pp. 302–303.

- Burnham & McGuigan (2010), p. 31.

- Oman (1903), p. 288.

- Reid (2019), p. 226.

- Bamford (2013), p. 249.

- Bamford (2013), pp. 249–250.

- Oman (1903), pp. 318–319.

- Oman (1903), p. 319.

- Oman (1903), pp. 344–345.

- Oman (1903), p. 345.

- Oman (1903), p. 318.

- Bamford (2013), p. 250.

- Oman (1903), pp. 352–353.

- Reid (2019), p. 235.

- Reid (2019), p. 236.

- Bamford (2013), p. 326.

- Glover (2001), p. 197.

- Bamford (2013), p. 200.

- Royal Military Calendar (1820), p. 303.

- Oman (1903), pp. 524–525.

- Chartrand (2013), p. 46.

- Oman (1903), p. 325.

- Chartrand (2013), p. 49.

- Oman (1903), p. 544.

- Chartrand (2013), p. 53.

- Chartrand (2013), p. 56.

- Chartrand (2013), p. 57.

- Chartrand (2013), p. 58.

- Chartrand (2013), p. 63.

- Burnham & McGuigan (2010), p. 265.

- Burnham & McGuigan (2010), p. 34.

- Burke (1868), p. 244.

- Clerke (1886), p. 141.

- Hill (2012), p. 94.

- Burnham & McGuigan (2010), p. 33.

- Reid (2004), p. 45.

- Bamford (2013), p. 201.

- Bamford (2013), p. 327.

- Reid (2019), p. 241.

- Hill (2012), p. 233.

- Hill (2012), pp. 93–94.

- Southey (1832), p. 480.

- Southey (1832), p. 481.

- Oman (1914), p. 323.

- Oman (1914), p. 329.

- Jones (1846), p. 233.

- Butler (1904), p. 518.

- Butler (1904), pp. 518–519.

- Napier (1910), p. 165.

- Oman (1914), p. 325.

- Butler (1904), p. 519.

- Jones (1846), pp. 237–238.

- Hill (2012), p. 95.

- Butler (1904), p. 520.

- Moon (2011), p. 252.

- Hill (2012), p. 116.

- Glover (2001), p. 200.

- Leslie (1974), p. 106.

- Worrall (2020), p. 9.

- Worrall (2020), pp. 7–8.

- Grodzinski (2013), p. 271.

- Urban (1834), p. 432.

- Every Saturday (1873), p. 717.

- Burke (1878), p. 296.

References

- Austen, Jane (2011). Deirdre Le Faye (ed.). Jane Austen's Letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957607-4.

- Bamford, Andrew (2013). Sickness, Suffering, and the Sword. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-4343-9.

- Burke, Bernard (1868). A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry. London: Harrison.

- Burke, Bernard (1878). A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage. London: Harrison.

- Burnham, Robert; McGuigan, Ron (2010). The British Army against Napoleon. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-84832-562-3.

- Butler, Lewis (1904). Wellington's Operations in the Peninsula (1808–1814). Vol. 2. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

- Carter, Thomas (1887). Historical Record of the Forty-Fourth, or the East Essex Regiment. Chatham: Gale & Polden.

- Chartrand, Rene (2013). Talavera 1809: Wellington's lightning strike into Spain. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-78096-182-8.

- Clerke, Agnes Mary (1886). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 07. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Every Saturday: A Journal of Choice Reading. Vol. 3. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company. 1873.

- Flayhart, William Henry (1992). Counterpoint to Trafalgar: The Anglo-Russian Invasion of Naples, 1805–1806. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-585-33858-3.

- Glover, Michael (2001). Wellington as Military Commander. London: Penguin Books.

- Grodzinski, John R. (2013). Defender of Canada: Sir George Prevost and the War of 1812. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-4387-3.

- Hill, Joanna (2012). Wellington's Right Hand: Rowland, Viscount Hill. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Spellmount. ISBN 978-0-7524-9013-7.

- Howard, Martin R. (2015). Death Before Glory! The British Soldier in the West Indies in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78159-341-7.

- Jones, John Thomas (1846). Journals of the Sieges carried on by the Army under the Duke of Wellington. Vol. 1. London: John Weale.

- Leslie, N. B. (1974). The Succession of Colonels of the British Army From 1660 to the Present Day. London and Aldershot: Society for Army Historical Research.

- Mackesy, Piers (2010). British Victory in Egypt. London: Tauris Parke. ISBN 978-1-84885-472-7.

- Moon, Joshua (2011). Wellington's Two Front War: The Peninsular Campaigns, at Home and Abroad, 1808–1814. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-4157-2.

- Napier, William (1910). English Battles and Sieges in the Peninsula. London: John Murray.

- Oman, Charles (1903). A History of the Peninsular War. Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Oman, Charles (1914). A History of the Peninsular War. Vol. 5. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Rosenburg, Chaim M. (2017). Losing America, Conquering India. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-6812-3.

- Southey, Robert (1832). History of the Peninsular War. Vol. 3. London: John Murray.

- Southey, Thomas (1827). Chronological History of the West Indies. Vol. 3. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green.

- Reid, Stuart (2004). Wellington's Army in the Peninsula 1809–14. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-517-4.

- Reid, Stuart (2019). Wellington's History of the Peninsular War: Battling Napoleon in Iberia 1808–1814. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Frontline Books.

- Syrett, David; DiNardo, R. L. (1994). The Commissioned Sea Officers of the Royal Navy 1660–1815. Aldershot, England: Scolar Press. ISBN 978-1-85928-122-2.

- The Royal Military Calendar, or Army Service and Commission Book. Vol. 2. London: A.J. Valpy. 1820.

- Urban, Sylvanus (1834). The Gentleman's Magazine. Vol. 2. London: William Pickering; John Bowyer Nichols and Son.

- Worrall, David (2020). "Jane Austen Goes to Drury Lane: Identifying Individuals in a Late Georgian Audience". Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film. 47: 3–25. doi:10.1177/1748372719900454. S2CID 213163179.