Chumar

Chumar or Chumur (Tibetan: ཆུ་མུར་, Wylie: chu mur) is a village and the centre of nomadic grazing region located in south-eastern Ladakh, India. It is in Rupshu block, south of the Tso Moriri lake, on the bank of the Parang River (or Pare Chu), close to Ladakh's border with Tibet.[1][2] Since 2012, China has disputed the border in this area, though the Chumur village itself is undisputed.[3][4]

Chumar

ཆུ་མུར་ Chumur | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Chumar Location in Ladakh, India  Chumar Chumar (India) | |

| Coordinates: 32.6693°N 78.5954°E | |

| Country | |

| Union Territory | Ladakh |

| District | Leh |

| Tehsil | Nyoma |

| Government | |

| • Type | Halqa Panchayat |

| Elevation | 5,100 m (16,700 ft) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Ladakhi, Hindi |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

Geography

Chumar is along the course of Pare Chu river, close to Ladakh's border with Tibet. The Pare Chu river originates in India's Himachal Pradesh, flows through Ladakh, and turns southeast near Chumar to flow into what the British called the 'Tsotso district' (now Tsosib Sumkyil Township) in Tibet's Tsamda County. After about 80 miles, Pare Chu reenters Himachal Pradesh again to join the Spiti River.[5]

The Chumar settlement itself is in a side valley of Pare Chu, on the bank of a stream, called Chumur Tokpo that flows down from Mount Shinowu. (32.7087°N 78.7273°E).[lower-alpha 1] There is also a historic gompa (Buddhist temple) near the village and a Chumur monastery further upstream. Along the course of Pare Chu and its tributary streams are numerous pastures and campgrounds utilised by the pastoral nomads of Rupshu. Some of them close to Pare Chu are listed as Sarlale, Takdible, Nirale, Tible, Lemarle and Chepzile.

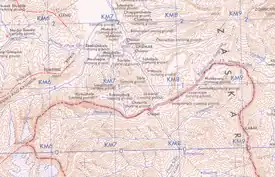

Chepzile is near a small hamlet called Chepzi which boasts some farmlands. Two tributaries join Pare Chu near the hamlet: the Kyumsalung Panglung (or simply Panglung) stream from the east, and the Chepzilung (or simply Chepzi) stream from the west. The Chepzilung originates below the Gya Peak, a key point on the border between Spiti (Himachal Pradesh) and Tibet.[7] According to the map drawn by Frederic Drew, who worked as a geologist in the administration of Jammu and Kashmir, these two tributaries were border rivers of Ladakh. The notes to the map he provided state that the subjects of Jammu and Kashmir grazed their cattle in the pasturelands up to the boundary, while the subjects of Tibet did likewise on their side.[8][9] (Map 2)

Indian boundary definition

By the time of Indian independence in 1947, the Indians appear to have conceded part of the valley of Chepzilung to the Tibetans.[lower-alpha 2] When independent India defined its boundaries in 1954, it also withdrew from the Panglung river east of Chepzi, and set the watershed ridge as the boundary. On the Pare Chu river itself, the Indian-defined border is five miles south of Chumar, which is approximately two miles north of Chepzi.[11] This allows the Tibetan graziers unrestricted access to both the tributary rivers of Pare Chu at Chepzi.

The combined effect of these decisions gave the appearance of a "bulge" in Indian territory near the Pare Chu river. The Indian government justified it on the grounds that the Ladakh's inhabitants had traditionally used the grazing lands along Pare Chu right up to Chepzi.[12]

The people of Chumar claim to have continued to use the farmland and grazing grounds at Chepzi until the recent past. They say that their access to these lands has been blocked by the People's Liberation Army in recent years.[13][14] The local nobility family of Rupshu continues to own the farmland and a palace at Chepzi.[15] The Indian Army has said that the Chepzi grazing grounds were "beyond the Indian borders."[16] But the locals are adamant that the Army does not understand their traditional grazing systems.[17]

Chinese claims

In the 1960 boundary talks with India, China claimed a boundary north of the Indian claim line. However it was still south of the general ridge line running across the Pare Chu valley.[18]

By 2012, China was claiming a boundary further north, representing a "bulge" of its own territory, as shown in the United States Office of the Geographer's boundary datasets. (Map 3)

Sino-Indian border dispute

Chumar has been one of the most active areas on the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in terms of interactions between Chinese and Indian troops. Located 190 km northwest of Zanda, it had long been an area of discomfort for the Chinese troops as, until 2014, Chumar had been one of the relatively few places along the Sino-Indian border where the Chinese had no roads near the LAC.[19][20]

According to Phunchok Stobdan, "In Chumar, China probably wants a straight border from PT (point) 4925 to PT 5318 to bring the Tible-Mane area under its control", in essence removing the bulge along the LAC at Chumar.[21] The Chinese opened up this new front of the border dispute in Chumar in 2012, prior to that, the border here was the International Border and not the Line of Actual Control.[3][4]

As part of the resolution to the 2013 Depsang standoff, the Indian side agreed to take down some bunkers in Chumar in return for the Chinese withdrawing from the Depsang standoff area.[22][23]

A road from Chumar leads up to the LAC. Along this road near the LAC, there is an Indian post at Point 30R, or known simply as 30R. 30R gets its name from being at a sharp elevation of 30 metres as compared to its surroundings.[24] PLA patrols often come up to 30R.[22] However they are at a tactical disadvantage since vehicles cannot come up to 30R; they have even tried using horses to enter the area.[24][22] The Chinese have tried constructing a road across 30R, including in 2014 when they claimed they had orders to build a road till Tible, but they have been stopped from doing so by India.[24][22] During the 2014 standoff here, Chinese troops had also positioned themselves on 30R, and had even heavy machinery with them for road construction.[25] Chinese troops have also been reported to have removed Indian surveillance cameras from the area.[22] The 2014 faceoff at Chumar, which started on 10 September, started days before the Chinese leader Xi Jinping visited India and continued even as he was in India.[26] Indian media quoting army source said that nearly 1000 Chinese soldiers had entered Indian territory in the Chumur sector on the day Xi was in India.[27]

Transport

Chumar is connected by arable roads to Rayul Lake nearly 50 km in the north, Hanle nearly 100 km in the east, Tso Moriri nearly 60 km north, Meroo on NH-3 nearly 225 km north.

In 2020, construction of a new ~150 km long road linking Chumar in Ladakh to Pooh in Himachal Pradesh was approved.[28]

See also

Notes

- Mount Shinowu (Chinese: 斯诺乌山; pinyin: Sī nuò wū shān) is a Chinese name of the peak. On Tibetan maps, the name is written as "Seru'Ur Ri" or "Zeru'Uri". British Indian maps do not give it a name but mark it as a peak of 21,030 feet (6,410 m) elevation.

- See the map by the US Army Map Service (AMS), which is based on the Survey of India maps from 1945.

References

- Panchayat Data, Government of Jammu and Kashmir, 2017. Accessed on 12 October 2020.

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), p. 278: "A village in the Rupshu district, on the left bank of the Para river, which here turns south and eventually joins the Sutlej."

- Datta, Sujan (17 September 2014). "Face-off on border on eve of Modi-Xi date". Telegraph India. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

Stobdan and sources in the Indian Army agree that they are a little taken aback by the Chinese opening up a "front" in Chumar that was undisputed till about two years back. The frontier along Tible-Mane, near Jammu and Kashmir's inter-state border with Himachal Pradesh, is recognised as the "International Boundary" and not as the "Line of Actual Control (LAC)".

- PTI, Chinese pitch seven tents in Chumar; stand off continues, The Economic Times, 22 September 2014. "In 2012, the PLA dropped some of its soldiers in this region and dismantled the makeshift storage tents of the Army and ITBP."

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak, Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1890, p. 654

- A. K. Singh, Yousuf Zaheer, The Continuing Story of Gya, The Himalayan Journal, Vol. 55, 199.

- Drew, The Jummoo and Kashmir Territories (1875), p. 496.

- Report of the Officials, Indian Report, Part 2 (1962), pp. 12–13.

- Large Scale International Boundaries (LSIB), Europe and Asia, 2012, EarthWorks, Stanford University, retrieved and annotated 11 October 2020.

- Report of the Officials, Indian Report, Part 1 (1962): "Thereafter [the boundary] turns westward and crosses the Pare river about five miles south of Chumar to reach Gya Peak ([Lat. and Long.] 32°32′N 78°24′E)."

- Report of the Officials, Indian Report, Part 2 (1962), p. 12: "Similarly, the inhabitants of Hanle and Rupshu Ilaqas have always been using the pastures lying south of Chumar up to the Chepzelung and Kumsanglung streams on either side of the Pare River."

- Ashiq, Peerzada (2 June 2020). "Uneasy frontier robs Ladakh's herders of pastures". The Hindu.

- Stanzin Dasal, How China Is Quietly Moving its Borders into India, VICE News, 3 August 2020.

- Safeena Wani, [https://thefederal.com/the-eighth-column/a-ladakhi-royal-family-fighting-chinese-land-grab-since-1980s https://thefederal.com/the-eighth-column/a-ladakhi-royal-family-fighting-chinese-land-grab-since-1980s/ A Ladakhi royal family fighting Chinese land grab since 1980s], The Federal, 3 July 2020.

- "Chabiji area beyond Indian borders: Army". The Hindu. 4 June 2020.

- Locals in Ladakh demand restoration of mobile services to ease war fear, The Economic Times, 5 June 2020.

- Report of the Officials, Chinese Report, Part 1 (1962), p. 5: "It then runs westwards and crosses the Pare River at its junction with a small stream (approximately 32°37′N 78°37′E) to reach the tri-junction of China's Ari district and India's Punjab [now Himachal Pradesh] and Ladakh (approximately 32°31′N 78°24′E)."

- Kondapalli, Srikanth (6 May 2013). "The fallout of China's Depsang plains transgression - Rediff.com India News". Rediff News. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- "China defends its latest incursion into Ladakh's Chumar sector". Indian Express. PTI. 10 July 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Datta, Sujan (17 September 2014). "Face-off on border on eve of Modi-Xi date". Telegraph India. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- "Indo-China stand-off worsens: Chinese pitch seven tents in Chumar". Deccan Chronicle. PTI. 22 September 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Joshi, Manoj (7 May 2013). "Making sense of the Depsang incursion". The Hindu. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Singh, Sushant (16 June 2020). "Explained: Six years ago, how a standoff in Ladakh ended after discussion". The Indian Express. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Fairclough, Gordon (30 October 2014). "India-China Border Standoff: High in the Mountains, Thousands of Troops Go Toe-to-Toe". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Gupta, Shishir (16 September 2014). "China, India in border skirmish ahead of Xi visit". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- "Nearly 1,000 Chinese soldiers enter India". Deccan Herald. 18 September 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Modi govt's infra push along China border — 2 new roads, alternate route to Daulat Beg Oldie, The Print, 15 September 2020.

Bibliography

- India, Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1962), Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question, Government of India Press

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak, Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1890

- Cunningham, Alexander (1854), Ladak: Physical, Statistical, Historical, London: Wm. H. Allen and Co – via archive.org

- Drew, Frederic (1875), The Jummoo and Kashmir Territories: A Geographical Account, E. Stanford – via archive.org

- Koshal, Sanyukta (2001), Ploughshares of Gods, Ladakh: Land, agriculture, and folk traditions, Om Publications, ISBN 978-81-86867-46-4

- Strachey, Henry (1854), Physical Geography of Western Tibet, London: William Clows and Sons – via archive.org

Further reading

- Aroor, Shiv (5 September 2013). "Chinese Army has occupied 640 square km in three Ladakh sectors, says report". India Today. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Tiwary, Deeptiman (8 January 2014). "Chinese troops enter Ladakh every 14 days". The Times of India. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

External links

- Article about the 2014 Chumar confrontation from Sina Military