Climate finance

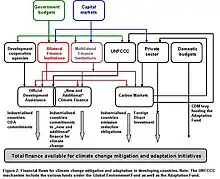

Climate finance are funding processes for investments related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. The term has been used in a narrower sense to refer to transfers of public resources from developed to developing countries, in light of their UN Climate Convention obligations to provide "new and additional financial resources". In a wider sense, the term refers to all financial flows relating to climate change mitigation and adaptation.[2][3]

| Part of a series on |

| Climate change and society |

|---|

The 21st session of the Conference of Parties (COP) to the UNFCCC (Paris 2015) introduced a new era for climate finance, policies, and markets. The Paris Agreement adopted there defined a global action plan to put the world on track to avoid dangerous climate change by limiting global warming to well below 2 °C above preindustrial levels. It includes climate financing channeled by national, regional and international entities for climate change mitigation and adaptation projects and programs. They include climate specific support mechanisms and financial aid for mitigation and adaptation activities to spur and enable the transition towards low-carbon, climate-resilient growth and development through capacity building, R&D and economic development.[4]

As of November 2020, development banks and private finance had not reached the US$100 billion per year investment stipulated in the UN climate negotiations for 2020.[5] However, in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic's economic downturn, 450 development banks pledged to fund a "Green recovery" in developing countries.[5]

Definition

Climate finance is "finance that aims at reducing emissions, and enhancing sinks of greenhouse gases and aims at reducing vulnerability of, and maintaining and increasing the resilience of, human and ecological systems to negative climate change impacts", as defined by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Standing Committee on Finance.[6]

The term has also been used in a narrower sense to refer to transfers of public resources from developed to developing countries, in light of their UN Climate Convention obligations to provide "new and additional financial resources". Furthermore, in a wider sense it is used to refer to all financial flows relating to climate change mitigation and adaptation.[2][3]

Types

Multilateral climate finance

The multilateral climate funds (i.e. governed by multiple national governments) are important for paying out money in climate finance. As of 2022, there are five multilateral climate funds coordinated by the UNFCCC. These are the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Adaptation Fund (AF), the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF) and the Global Environment Facility (GEF). The largest of these, the GCF, was formed in 2010. [9][10]

The other main multilateral fund, Climate Investment Funds (CIFs), is coordinated by the World Bank. The Climate Investment Funds has been important in climate finance since 2008.[11][12] The Climate-Smart Urbanization Program is an initiative by the Climate Investment Funds (CIFs) meant to support cities. The City Climate Finance Gap Fund assists cities in implementing infrastructure development projects that are low-carbon, pushing investments for climate and "green" objectives through technical help for early-stage planning and project preparation. The Gap Fund was launched during the 2019 UN Climate Action Conference and began operations in September 2020. It is sponsored by Germany and Luxembourg and implemented by the World Bank and the European Investment Bank.[13]

Most multilateral climate funds use a wide range of financing instruments, including grants, debt, equity, and risk mitigation options. These are intended to crowd in other sources of finance, whether from domestic governments, other donors, or the private sector.

Finance committed and dispersed

In 2016, the main four funds approved $2.78 billion of project support. India received the largest total amount of single-country support, followed by Ukraine and Chile. Tuvalu received the most funding per person, followed by Samoa and Dominica. The US is the largest donor across the four funds, while Norway makes the largest contribution relative to population size.[14]

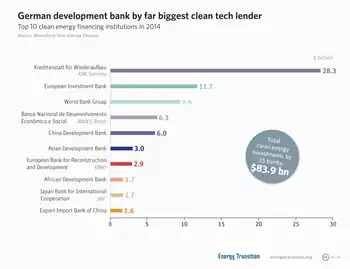

Climate financing by the world's six largest multilateral development banks (MDBs) rose to a seven-year high of $35.2 billion in 2017. According to IRENA, the global energy transition could contribute $19 trillion in economic gains by 2050.

Since 2012, the European Investment Bank has provided €170 billion in climate funding, which has funded over €600 billion in programs to mitigate emissions and help people respond to climate change and biodiversity depletion across Europe and the world.[15][16] In 2022, the Bank's funding for climate change and environmental sustainability projects totaled €36.5 billion. This includes €35 billion for initiatives supporting climate action and €15.9 billion for programs supporting environmental sustainability goals. Projects with combined climate action and environmental sustainability advantages received €14.3 billion in funding.[17]

Over 2021-2030, the EIB Group wants to assist €1 trillion in green investment.[18] Currently, only 5.4% of the Group's loans for climate action are dedicated to climate adaptation, but funding did increase significantly in 2022, reaching €1.9 billion.[19]

In 2009, developed countries committed to jointly mobilize $100 billion annually in climate finance by 2020 to support developing countries in reducing emissions and adapting to climate change.[20] They claim that climate finance provided and mobilized reached $83.3bn in 2020. But the money given for climate change was only worth about a third of what was said ($21–24.5bn).[21]

Debt-for-climate swaps

Debt-for-climate swaps happen where debt accumulated by a country is repaid upon fresh discounted terms agreed between the debtor and creditor, where repayment funds in local currency are redirected to domestic projects that boost climate mitigation and adaptation activities.[22] Climate mitigation activities that can benefit from debt-for-climate swaps includes projects that enhance carbon sequestration, renewable energy and conservation of biodiversity as well as oceans.

For instance, Argentina succeed in carrying out such a swap which was implemented by the Environment Minister at the time, Romina Picolotti. The value of debt addressed was $38,100,000 and the environmental swap was $3,100,000 which was redirected to conservation of biodiversity, forests and other climate mitigation activities.[23] Seychelles in collaboration with the Nature Conservancy also undertook a similar debt-for-nature swap where $27 million of debt was redirected to establish marine parks, ocean conservation and ecotourism activities.[24]

Private climate finance

Public finance has traditionally been a significant source of infrastructure investment. However, public budgets are often insufficient for larger and more complex infrastructure projects, particularly in lower-income countries. Climate-compatible investments often have higher investment needs than conventional (fossil fuel) measures,[25] and may also carry higher financial risks because the technologies are not proven or the projects have high upfront costs.[26] If countries are going to access the scale of funding required, it is critical to consider the full spectrum of funding sources and their requirements, as well as the different mechanisms available from them, and how they can be combined.[27] There is therefore growing recognition that private finance will be needed to cover the financing shortfall.

Private investors could be drawn to sustainable urban infrastructure projects where a sufficient return on investment is forecast based on project income flows or low-risk government debt repayments. Bankability and creditworthiness are therefore prerequisites to attracting private finance.[28] Potential sources of climate finance include commercial banks, investment companies, pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds. These different investor types will have different risk-return expectations and investment horizons, and projects will need to be structured appropriately.[29]

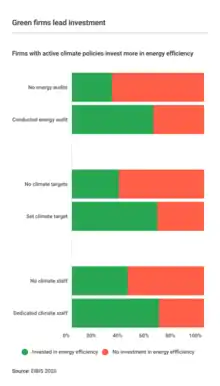

During the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change was addressed by 43% of EU enterprises. Despite the pandemic's effect on businesses, the percentage of firms planning climate-related investment rose to 47%. This was a rise from 2020, when the percentage of climate related investment was at 41%.[30][31] Climate investment in Europe as been growing this decade. However, the need for the EU's "Fit for 55" climate package remains 356 billion euros a year. Since 2020, US firms' desire to innovate has increased, whereas European firms' has decreased.[32] As of 2022, spending in climate for European enterprises has climbed by 10%, reaching 53% on average. This has been especially noticeable in Central and Eastern Europe at 25% and in small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) with a 22% increase in climate financing.[33]

Quantifying current flows of climate finance

| Part of a series about |

| Environmental economics |

|---|

|

A number of initiatives are underway to monitor and track flows of international climate finance.[34] Analysts at Climate Policy Initiative have tracked public and private sector climate finance flows from a variety of sources on a yearly basis since 2011. In 2019, they estimated that annual climate finance reached more than US$600 billion.[35] This work has fed into the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows [36] and the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report chapter on climate finance. This and other research suggest a need for more efficient monitoring of climate finance flows.[37] In particular, they suggest that funds can do better at synchronizing their reporting of data, being consistent in the way that they report their figures, and providing detailed information on the implementation of projects and programs over time.

The estimates of the climate finance gap - that is, the shortfall in investment - vary according to the geographies, sectors and activities included, timescale and phasing, target and the underlying assumptions.

Finance for mitigation

Global climate finance is heavily focused on mitigation. Key sectors for investment have been renewable energy, energy efficiency and transport.[38]: 1549, 1564 There has also been an increase in international climate finance towards the 100 billion target. Most of the estimated US$83.3 billion provided to developing countries in 2020, was targeted at mitigation (US$48.6 billion, or 58%).[39] Global energy investment has increased since the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic crisis. However, the crisis has placed a great additional strain on the global economy, debt and the availability of finance, which is expected to be felt in years to come.[38]: 1555

A meta-analysis from 2023 investigated the "required technology-level investment shifts for climate-relevant infrastructure until 2035" within the EU, and found these are "most drastic for power plants, electricity grids and rail infrastructure", ~87€ billion above the planned budgets in the near-term (2021–25), and in need of sustainable finance policies.[40][41]

In 2010, the World Development Report preliminary estimates of financing needs for mitigation and adaptation activities in developing countries range from $140 to 175 billion per year for mitigation over the next 20 years with associated financing needs of $265–565 billion and $30–100 billion a year over the period 2010–2050 for adaptation.[42]

The International Energy Agency's 2011 World Energy Outlook (WEO) estimates that in order to meet the growing demand for energy through 2035, $16.9 trillion in new investment for new power generation is projected, with renewable energy (RE) comprising 60% of the total.[43] The capital required to meet projected energy demand through 2030 amounts to $1.1 trillion per year on average, distributed (almost evenly) between the large emerging economies (China, India, Brazil, etc.) and the remaining developing countries.[44] It is believed that over the next 15 years, the world will require about $90 trillion in new infrastructure – most of it in developing and middle-income countries.[45] The IEA estimates that limiting the rise in global temperature to below 2 Celsius by the end of the century will require an average of $3.5 trillion a year in energy sector investments until 2050.[45]

Society and culture

It has been estimated that only 0.12% of all funding for climate-related research is spent on the social science of climate change mitigation.[46] Vastly more funding is spent on natural science studies of climate change and considerable sums are also spent on studies of the impact of and adaptation to climate change.[46] It has been argued that this is a misallocation of resources, as the most urgent puzzle at the current juncture is to work out how to change human behavior to mitigate climate change, whereas the natural science of climate change is already well established and there will be decades and centuries to handle adaptation.[46]

See also

References

- "World Energy Investment 2023 / Overview and key findings". International Energy Agency (IEA). 25 May 2023. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023.

Global energy investment in clean energy and in fossil fuels, 2015-2023 (chart)

— From pages 8 and 12 of World Energy Investment 2023 (archive). - Oscar Reyes (2013), "A Glossary of Climate Finance Terms", Institute for Policy Studies, Washington DC, p. 10 and 11

- "Search | Eldis".

- Barbara Buchner, Angela Falconer, Morgan Hervé-Mignucci, Chiara Trabacchi and Marcel Brinkman (2011) "The Landscape of Climate Finance" A CPI Report, Climate Policy Initiative, Venice (Italy), p. 1 and 2.

- "Banks around world in joint pledge on 'green recovery' after Covid". the Guardian. 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- "Documents | UNFCCC". unfccc.int. Retrieved 2018-09-08.

- "Firms brace for climate change". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-10-12.

- European Investment Bank (2021-01-21). EIB Investment Report 2020/2021: Building a smart and green Europe in the COVID-19 era. European Investment Bank. doi:10.2867/904099. ISBN 978-92-861-4811-8.

- "Climate Finance | UNFCCC". unfccc.int. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- Global, IndraStra. "Climate Finance: Essential Components, Existing Challenges, and On-going Initiatives". IndraStra Global. ISSN 2381-3652. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- "Climate Investment Opportunities in Cities - An IFC Analysis". www.ifc.org. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- "10 Years of Climate Action". Climate Investment Funds. 2019-05-31. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- Bank, European Investment (2023-02-02). "Climate Action and Environmental Sustainability Overview 2023".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Mapped: Where multilateral climate funds spend their money". Carbon Brief. 2017.

- "CIS Interview: Vice President Ambroise Fayolle, the European Investment Bank". CIS. 2020-10-27. Retrieved 2021-05-18.

- "A plan for the long haul to contribute finance to the European Green Deal". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2021-05-18.

- Bank, European Investment (2023-02-02). "Climate Action and Environmental Sustainability Overview 2023".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Bank, European Investment (2023-06-29). EIB Group Sustainability report 2022. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5543-7.

- "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- Bos, Julie; Gonzalez, Lorena; Thwaites, Joe (7 October 2021). "Are Countries Providing Enough to the $100 Billion Climate Finance Goal?". Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- "climate finance Short Changed" (PDF). OXFAM. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Picolotti, Romina; Zaelke, Durwood; Silverman-Roati, Korey; Ferris, Richard (2020). "Debt-for-Climate Swaps" (PDF). Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development: 3.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Debt-for-Climate Swaps Can Help Developing Countries Make a Green Recovery". Sustainable Recovery 2020. November 13, 2020. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- Goering, Laurie (2020-09-07). "Debt swaps could free funds to tame climate, biodiversity and virus threats". Reuters. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- Gouldson A, Colenbrander S, Sudmant A, McAnulla F, Kerr N, Sakai P, Hall S, Papargyropoulou E, Kuylenstierna J (2015). "Exploring the economic case for climate action in cities". Global Environmental Change. 35: 93–105. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.07.009.

- Schmidt, TS (2014). "Low-carbon investment risks and de-risking". Nature Climate Change. 4 (4): 237–239. Bibcode:2014NatCC...4..237S. doi:10.1038/nclimate2112.

- Understanding 'bankability' and unlocking climate finance for climate compatible development, Climate & Development Knowledge Network, 31 July 2017

- Colenbrander S, Lindfield M, Lufkin J, Quijano N (2018). "Financing Low-Carbon, Climate-Resilient Cities" (PDF). Coalition for Urban Transitions. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-04-12. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- Floater G, Dowling D, Chan D, Ulterino M, Braunstein J, McMinn T, Ahmad E (2017). "Global Review of Finance for Sustainable Urban Infrastructure". Coalition for Urban Transitions.

- Bank, European Investment (2022-01-12). EIB Investment Report 2021/2022: Recovery as a springboard for change. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5155-2.

- "Latest EIB survey: The state of EU business investment 2021". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- "European investment offensive needed to keep up with US subsidies". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- Bank, European Investment (2023-04-12). What drives firms’ investment in climate change? Evidence from the 2022-2023 EIB Investment Survey. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5537-6.

- "Global Landscape of Climate Finance, A Decade of Data: 2011-2020" (PDF). CPI. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- "Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019". CPI.

- "Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows | UNFCCC". unfccc.int.

- "Watson, C., Nakhooda, S., Caravani, A. and Schalatek, L. (2012) The practical challenges of monitoring climate finance: Insights from Climate Funds Update. Overseas Development Institute Briefing Paper" (PDF).

- Kreibiehl, S., T. Yong Jung, S. Battiston, P. E. Carvajal, C. Clapp, D. Dasgupta, N. Dube, R. Jachnik, K. Morita, N. Samargandi, M. Williams, 2022: Investment and finance. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. doi: 10.1017/9781009157926.017

- OECD (2022), Aggregate trends of Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2020, https://www.oecd.org/climate-change/finance-usd-100-billion-goal.

- "Studie sieht EU-weit 87 Milliarden Euro Mehrbedarf bei Erneuerbaren und E-Verkehr | MDR.DE". www.mdr.de (in German). Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- Klaaßen, Lena; Steffen, Bjarne (January 2023). "Meta-analysis on necessary investment shifts to reach net zero pathways in Europe". Nature Climate Change. 13 (1): 58–66. Bibcode:2023NatCC..13...58K. doi:10.1038/s41558-022-01549-5. ISSN 1758-6798. S2CID 255624692.

- Expert reviews of the study: "Notwendige Investitionen auf dem Weg zu Netto-Null-Emissionen". www.sciencemediacenter.de. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- World Bank Group(2010), "World Development Report 2010: Development and Climate Change, World Bank Groupe, Washington DC, ch. 6, p. 257

- International Energy Agency (2011). World Energy Outlook 2011, OECD and IEA, Paris (France), Part B, ch.2

- International Energy Agency (2011). World Energy Outlook 2011}, OECD and IEA, Paris (France), Part B, ch.2

- "Climate Finance". World Bank. Retrieved 2018-09-08.

- Overland, Indra; Sovacool, Benjamin K. (2020-04-01). "The misallocation of climate research funding". Energy Research & Social Science. 62: 101349. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.101349. ISSN 2214-6296.

External links

- Climate Finance Landscape - Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019