Effects of climate change on small island countries

The effect of climate change on small island countries can be extreme because of low-lying coasts, relatively small land masses, and exposure to extreme weather.[2] The effects of climate change, particularly sea level rise and increasingly intense tropical cyclones, threaten the existence of many island countries, island peoples and their cultures, and will alter their ecosystems and natural environments. Several Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are among the most vulnerable nations to climate change.

| Part of a series on |

| Climate change and society |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Climate change |

|---|

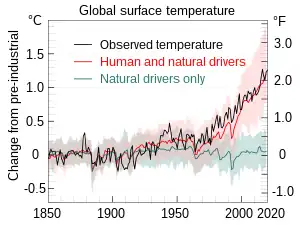

Changes in global surface temperature over the past 170 years (black line) relative to 1850–1900. |

Some small and low population islands are without adequate resources to protect their islands, inhabitants, and natural resources. In addition to the risks to human health, livelihoods, and inhabitable space, the pressure to leave islands is often barred by the inability to access the resources needed to relocate. The nations of the Caribbean, Pacific Islands and Maldives are already experiencing considerable impacts of climate change, making efforts to implement climate change adaptation a critical issue for them.[3]

Efforts to combat these environmental changes are ongoing and multinational. Due to their vulnerability and limited contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, some island countries have made advocacy for global cooperation on climate change mitigation a key aspect of their foreign policy. Governments face a complex task when combining gray infrastructure with green infrastructure and nature-based solutions to help with disaster risk management in areas such as flood control, early warning systems, nature-based solutions, and integrated water resource management.[4] As of March 2022, the Asian Development Bank has committed $3.62 billion to help small island developing states with climate change, transport, energy, and health projects.[5]

Greenhouse gas emissions

Small Island Developing States make minimal contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions, with a combined total of less than 1%.[6][3] However, that does not indicate that greenhouse emissions are not produced at all, and it is recorded that the annual total greenhouse gas emissions from islands could range from 292.1 to 29,096.2 [metric] tonne CO2-equivalent.[7]

Impacts on the natural environment

Expected impacts on small islands include:[8]

- extreme weather events

- changes in sea level

- increased sensitivity and exposure to the effects of climate change.

- deterioration in coastal conditions, such as beach erosion and coral bleaching, which will likely affect local resources such as fisheries, as well as the value of tourism destinations.

- increased inundation, storm surge, erosion, and other coastal hazards caused by sea-level rise, threatening vital infrastructure, settlements, and facilities that support the livelihood of island communities.

- reduction of already limited water resources to the point that they become insufficient to meet demand during low-rainfall periods by mid-century, especially on small islands (such as in the Caribbean and the Pacific Ocean)

- invasion by non-native species increasing with higher temperatures, particularly in mid- and high-latitude islands.

There are many secondary effects of climate change and sea-level rise particular to island nations. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, climate change in the Pacific Islands will cause "continued increases in air and ocean surface temperatures in the Pacific, increased frequency of extreme weather events, and increased rainfall during the summer months and a decrease in rainfall during the winter months".[9] This would entail distinct changes to the small, diverse, and isolated island ecosystems and biospheres present within many of these island nations.

Sea level rise

One of the dominant manifestations of climate change is sea level rise. NOAA estimates that "since 1992, new methods of satellite altimetry (the measurement of elevation or altitude) indicate a rate of rise of 0.12 inches per year".[10] Similarly NASA calculates that the average sea level rise is 3.41 mm per year and that sea-level rise is directly caused by the expansion of water as it warms and the melting of polar ice caps.[11] Both of these changes are dependent on global warming as a result of climate change. Sea level rise is especially threatening to low-lying island nations because seas are encroaching upon limited habitable land and threatening existing cultures.[12][13] Stefan Rahmstorf, a professor of Ocean Physics at Potsdam University in Germany notes "even limiting warming to 2 degrees, in my view, will still commit some island nations and coastal cities to drown."[14]

Research published in 2015 contradicts the claim that rising sea levels will necessarily submerge island nations. Studies by Paul Kench, a geomorphologist at the University of Auckland, have shown that "reef islands change shape and move around in response to shifting sediments, and that many of them are growing in size, not shrinking, as sea level inches upward". At the same time Kench says that "for the areas that have been transformed by human development, such as the capitals of Kiribati, Tuvalu, and the Maldives, the future is considerably gloomier" because these islands cannot adapt to rising sea levels and are therefore greatly threatened.[15]

Impacts on people

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned in 2001 that small island countries will experience considerable economic and social consequences due to climate change.[16]

A study that engaged the experiences of residents in atoll communities found that the cultural identities of these populations are strongly tied to these lands.[17] Human rights activists argue that the potential loss of entire atoll countries, and consequently the loss of national sovereignty, self-determination, cultures, and indigenous lifestyles cannot be compensated for financially.[18][19] Some researchers suggest that the focus of international dialogues on these issues should shift from ways to relocate entire communities to strategies that instead allow for these communities to remain on their lands.[18][17]

Agriculture and fisheries

Climate change poses a risk to food security in many Pacific Islands, impacting fisheries and agriculture.[20] As sea level rises, island nations are at increased risk of losing coastal arable land to degradation as well as salination. Once the limited available soil on these islands becomes salinated, it becomes very difficult to produce subsistence crops such as breadfruit. This would severely impact the agricultural and commercial sector in nations such as the Marshall Islands and Kiribati.[21]

In addition, local fisheries would also be affected by higher ocean temperatures and increased ocean acidification. As ocean temperatures rise and the pH of oceans decreases, many fish and other marine species would die out or change their habits and range. As well as this, water supplies and local ecosystems such as mangroves, are threatened by global warming.[22]

Economic impacts

SIDS may also have reduced financial and human capital to mitigate climate change risk, as many rely on international aid to cope with disasters like severe storms. Worldwide, climate change is projected to have an average annual loss of 0.5% GDP by 2030; in Pacific SIDS, it will be 0.75–6.5% GDP by 2030. Caribbean SIDS will have average annual losses of 5% by 2025, escalating to 20% by 2100 in projections without regional mitigation strategies.[23] The tourism sector of many island countries is particularly threatened by increased occurrences of extreme weather events such as hurricanes and droughts.[22]

Public health

Climate change impacts small island ecosystems in ways that have a detrimental effect on public health. In island nations, changes in sea levels, temperature, and humidity may increase the prevalence of mosquitoes and diseases carried by them such as malaria and Zika virus. Rising sea levels and severe weather such as flooding and droughts may render agricultural land unusable and contaminate freshwater drinking supplies. Flooding and rising sea levels also directly threaten populations, and in some cases may be a threat to the entire existence of the island.[24]

Mitigation and adaptation

Relocation and migration

Climate migration has been discussed in popular media as a potential adaptation approach for the populations of islands threatened by sea level rise. A 2015 review in Climatic Change found that these depictions are often sensationalist or problematic, although migration may likely form a part of adaptation. Mobility has long been a part of life in islands, but could be used in combination with local adaptation measures.[3]

Climate resilient economies

Many SIDS now understand the need to move towards low-carbon, climate resilient economies, as set out in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) implementation plan for climate change-resilient development. SIDS often rely heavily on imported fossil fuels, spending an ever-larger proportion of their GDP on energy imports. Renewable technologies have the advantage of providing energy at a lower cost than fossil fuels and making SIDS more sustainable. Barbados has been successful in adopting the use of solar water heaters (SWHs). A 2012 report published by the Climate & Development Knowledge Network showed that its SWH industry now boasts over 50,000 installations. These have saved consumers as much as US$137 million since the early 1970s. The report suggested that Barbados' experience could be easily replicated in other SIDS with high fossil fuel imports and abundant sunshine.[25]

International cooperation

The governments of several island nations have made political advocacy for greater international ambition on climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation a component of their foreign policy and international alliances.[26] The Alliance of Small Island States (ASIS) have had some sway in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.[27] The 43 members of the alliance have held the position of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, and advocated for this at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, influencing the goals of the Paris Agreement.[28][29] Marshall Islands Prime Minister Tony deBrum was central in forming the High Ambition Coalition at the conference.[30] Meetings of the Pacific Islands Forum have also discussed the issue.[31]

The Maldives and Tuvalu particularly have played a prominent role on the international stage. In 2002, Tuvalu threatened to sue the United States and Australia in the International Court of Justice for their contribution to climate change and for not ratifying the Kyoto Protocol.[27] The governments of both of these countries have cooperated with environmental advocacy networks, non-governmental organisations and the media to draw attention to the threat of climate change to their countries. At the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference, Tuvalu delegate Ian Fry spearheaded an effort to halt negotiations and demand a comprehensive, legally binding agreement.[27]

By country and region

Caribbean

East Timor

East Timor's agriculture and food security is threatened by climate change. Sea level rise also threatens its coastal areas, including capital city Dili.[39]

Maldives

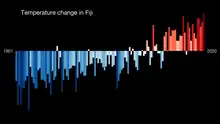

Fiji

Climate change in Fiji is an exceptionally pressing issue for the country - as an island nation, Fiji is particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels, coastal erosion and extreme weather.[40] These changes, along with temperature rise, will displace Fijian communities and will prove disruptive to the national economy - tourism, agriculture and fisheries, the largest contributors to the nation's GDP, will be severely impacted by climate change causing increases in poverty and food insecurity.[40] As a party to both the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Climate Agreement, Fiji hopes to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 which, along with national policies, will help to mitigate the impacts of climate change.[41]

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative finds that the climate crisis has worsened human rights conditions moderately (4.6 out of 6) in Fiji.[42]Kiribati

.jpg.webp)

The existence of the nation of Kiribati is imperilled by rising sea levels, with the country losing land every year.[43] Many of its islands are currently or becoming inhabitable due to their shrinking size. Thus, the majority of the country's population resides in only a handful of islands, with more than half of its residents living on one island alone, Tarawa. This leads to other issues such as severe overcrowding in such a small area.[44] In 1999, the uninhabited islands of Tebua Tarawa and Abanuea both disappeared underwater.[45] The government's Kiribati Adaptation Program was launched in 2003 to mitigate the country's vulnerability to the issue.[46] In 2008, fresh water supplies began being encroached by seawater, prompting President Anote Tong to request international assistance to begin relocating the country's population elsewhere.[47]

Marshall Islands

.jpg.webp)

Palau

The Palau government are concerned about the effects of climate change on the island nation. In 2008 Palau requested that the UN Security Council consider protection against rising sea levels due to climate change.[50]

Tommy Remengesau, the president of Palau, has said:[51]

Palau has lost at least one third of its coral reefs due to climate change related weather patterns. We also lost most of our agricultural production due to drought and extreme high tides. These are not theoretical, scientific losses -- they are the losses of our resources and our livelihoods.... For island states, time is not running out. It has run out. And our path may very well be the window to your own future and the future of our planet.

Solomon Islands

Between 1947 and 2014, six islands of the Solomon Islands disappeared due to sea level rise, while another six shrunk by between 20 and 62 per cent. Nuatambu Island was the most populated of these with 25 families living on it; 11 houses washed into the sea by 2011.[52]

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative[53] finds that the climate crisis has worsened human rights conditions in the Solomon Islands greatly (5.0 out of 6). [54] Human rights experts provided that the climate crisis has contributed to conflict in communities, negative future socio-economic outlook, and food instability. [55]

Tuvalu

Tuvalu is a small Polynesian island nation located in the Pacific Ocean. It can be found about halfway between Hawaii and Australia. It is made up of nine tiny islands, five of which are coral atolls while the other four consists of land rising from the sea bed. All are low-lying islands with no point on Tuvalu being higher than 4.5m above sea level.[56] Beside Funafuti, the capital of Tuvalu, sea-level rise is estimated at 1.2 ± 0.8 mm/year.[57] As well as this, the dangerous peak high tides in Tuvalu are becoming higher causing greater danger. In response to sea level rise, Tuvalu is considering resettlement plans in addition to pushing for increased action in confronting climate change at the UN.[58]

São Tomé and Príncipe

Seychelles

In the Seychelles, the impacts of climate change were observable in precipitation, air temperature and sea surface temperature by the early 2000s. Climate change poses a threat to its coral reef ecosystems, with drought conditions in 1999 and a mass bleaching event in 1998. Water management will be critically impacted.[16]

Singapore

See also

References

- Simon Albert; Javier X Leon; Alistair R Grinham; John A Church; Badin R Gibbes; Colin D Woodroffe (1 May 2016). "Interactions between sea-level rise and wave exposure on reef island dynamics in the Solomon Islands". Environmental Research Letters. 11 (5): 054011. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/5/054011. ISSN 1748-9326. Wikidata Q29028186.

- IPCC, 2014. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Barros, V.R., C.B. Field, D.J. Dokken, M.D. Mastrandrea, K.J. Mach, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US, pp. 688.

- Betzold, Carola (1 December 2015). "Adapting to climate change in small island developing states". Climatic Change. 133 (3): 481–489. Bibcode:2015ClCh..133..481B. doi:10.1007/s10584-015-1408-0. ISSN 1573-1480. S2CID 153937782.

- "ADB's Work on Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management". Asian Development Bank. 11 November 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- "ADB's Work in FCAS and SIDS". Asian Development Bank. 30 March 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- Wong, Poh Poh (27 September 2010). "Small island developing states". WIREs Climate Change. 2 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1002/wcc.84. ISSN 1757-7780. S2CID 130010252.

- Chen, Ying-Chu (2017). "Evaluation of greenhouse gas emissions from waste management approaches in the islands". Waste Management & Research. 35 (7): 691–699. doi:10.1177/0734242X17707573. PMID 28553773. S2CID 20731727. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

-

This article incorporates public domain material from International Impacts & Adaptation: Climate Change: US EPA. US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). 14 June 2012.

This article incorporates public domain material from International Impacts & Adaptation: Climate Change: US EPA. US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). 14 June 2012.

- "Climate Change in the Pacific Islands". US Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008.

- "Is Sea Level Rising?" Is Sea Level Rising? NOAA, undated, accessed 21 February 2016. http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/sealevel.html.

- "Sea Level." NASA, undated, accessed 21 February 2016. <https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/sea-level/>.

- Leatherman, Stephen P.; Beller-Simms, Nancy (1997). "Sea-Level Rise and Small Island States: An Overview". Journal of Coastal Research: 1–16. ISSN 0749-0208. JSTOR 25736084.

- Neumann, Barbara; Vafeidis, Athanasios T.; Zimmermann, Juliane; Nicholls, Robert J. (11 March 2015). "Future Coastal Population Growth and Exposure to Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Flooding - A Global Assessment". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0118571. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1018571N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118571. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4367969. PMID 25760037.

- Sutter, John D. "Life in a Disappearing Country." CNN. Cable News Network, undated, accessed 28 January 2016. http://www.cnn.com/interactive/2015/06/opinions/sutter-two-degrees-marshall-islands/

- Warne, Kennedy (13 February 2015). "Will Pacific Island Nations Disappear as Seas Rise? Maybe Not". National Geographic.

- Payet, Rolph; Agricole, Wills (June 2006). "Climate Change in the Seychelles: Implications for Water and Coral Reefs". Ambio: A Journal of the Human Environment. 35 (4): 182–189. doi:10.1579/0044-7447(2006)35[182:CCITSI]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0044-7447. PMID 16944643. S2CID 39117934.

- Mortreux, Colette; Barnett, Jon (2009). "Climate change, migration and adaptation in Funafuti, Tuvalu". Global Environmental Change. 19 (1): 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.09.006.

- Tsosie, Rebecca (2007). "Indigenous People and Environmental Justice:The Impact of Climate Change". University of Colorado Law Review. 78: 1625.

- Barnett, Jon; Adger, W. Neil (December 2003). "Climate Dangers and Atoll Countries". Climatic Change. 61 (3): 321–337. doi:10.1023/B:CLIM.0000004559.08755.88. S2CID 55644531.

- Barnett, Jon (1 March 2011). "Dangerous climate change in the Pacific Islands: food production and food security". Regional Environmental Change. 11 (1): 229–237. doi:10.1007/s10113-010-0160-2. ISSN 1436-378X. S2CID 155030232.

- "Climate Change Impacts - Pacific Islands -." The Global Mechanism (n.d.): n.pag. IFAD. Web. 21 February 2016. http://www.ifad.org/events/apr09/impact/islands.pdf.

- giz. "Coping with climate change in the Pacific island region". www.giz.de. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- Thomas, Adelle; Baptiste, April; Martyr-Koller, Rosanne; Pringle, Patrick; Rhiney, Kevon (17 October 2020). "Climate Change and Small Island Developing States". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-083355. ISSN 1543-5938.

- "Climate change and its impact on health on small island developing states". World Health Organization. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- Seizing the sunshine – Barbados' thriving solar water heater industry, Climate & Development Knowledge Network, 17 September 2012.

- Thomas, Adelle; Baptiste, April; Martyr-Koller, Rosanne; Pringle, Patrick; Rhiney, Kevon (17 October 2020). "Climate Change and Small Island Developing States". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-083355. ISSN 1543-5938. S2CID 219509170.

- Jaschik, Kevin (1 March 2014). "Small states and international politics: Climate change, the Maldives and Tuvalu". International Politics. 51 (2): 272–293. doi:10.1057/ip.2014.5. ISSN 1740-3898. S2CID 145290890.

- "A tiny island in the Pacific Ocean is about to be completely destroyed". The Independent. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "This is why these Pacific islands need the Paris climate change deal to succeed". The Independent. 12 December 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "How the historic Paris deal over climate change was finally agreed". the Guardian. 13 December 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Pacific islands demand climate action as China, US woo region". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- Beckford, Clinton L.; Rhiney, Kevon (2016). "Geographies of Globalization, Climate Change and Food and Agriculture in the Caribbean". In Clinton L. Beckford; Kevon Rhiney (eds.). Globalization, Agriculture and Food in the Caribbean. Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-53837-6. ISBN 978-1-137-53837-6.

- Ramón Bueno; Cornella Herzfeld; Elizabeth A. Stanton; Frank Ackerman (May 2008). The Caribbean and climate change: The costs of inaction (PDF).

- Winston Moore; Wayne Elliot; Troy Lorde (1 April 2017). "Climate change, Atlantic storm activity and the regional socio-economic impacts on the Caribbean". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 19 (2): 707–726. doi:10.1007/s10668-016-9763-1. ISSN 1387-585X. S2CID 156828736.

- Sealey-Huggins, Leon (2 November 2017). "'1.5°C to stay alive': climate change, imperialism and justice for the Caribbean". Third World Quarterly. 38 (11): 2444–2463. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1368013.

- BERARDELLI, JEFF (29 August 2020). "Climate change may make extreme hurricane rainfall five times more likely, study says". CBC News. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- Clement Lewsey; Gonzalo Cid; Edward Kruse (1 September 2004). "Assessing climate change impacts on coastal infrastructure in the Eastern Caribbean". Marine Policy. 28 (5): 393–409. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2003.10.016.

- Borja G. Reguero; Iñigo J. Losada; Pedro Díaz-Simal; Fernando J. Méndez; Michael W. Beck (2015). "Effects of Climate Change on Exposure to Coastal Flooding in Latin America and the Caribbean". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0133409. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1033409R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133409. PMC 4503776. PMID 26177285.

- Barnett, Jon; Dessai, Suraje; Jones, Roger N. (July 2007). "Vulnerability to Climate Variability and Change in East Timor". Ambio: A Journal of the Human Environment. 36 (5): 372–378. doi:10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[372:VTCVAC]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0044-7447. PMID 17847801. S2CID 29460148.

- COP23. "How Fiji is Affected by Climate Change". Cop23.

- UN Climate Change News (5 March 2019). "Fiji Submits Long-Term National Climate Plan". unfccc.int. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- "Fiji - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ABC News. "Kiribati's President: "Our Lives Are At Stake"". ABC News. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- Storey, Donovan; Hunter, Shawn (2010). "Kiribati: an environmental 'perfect storm". Australian Geographer. 41 (2): 167–181. doi:10.1080/00049181003742294. S2CID 143231470. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- "BBC News | Sci/Tech | Islands disappear under rising seas". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- "Kiribati Adaptation Program (KAP) | Climate Change". Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- "Paradise lost: climate change forces South Sea islanders to seek". The Independent. 5 June 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- "Human Rights Measurement Initiative – The first global initiative to track the human rights performance of countries". humanrightsmeasurement.org. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- "Marshall Islands - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- "Palau seeks Security Council protection on climate change". Global Dashboard. 16 February 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- "Palau president challenges Hawai'i to take action against global warming". Hawaii Independent. 14 October 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- "Five Pacific islands vanish from sight as sea levels rise". New Scientist. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- "Human Rights Measurement Initiative – The first global initiative to track the human rights performance of countries". humanrightsmeasurement.org. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- "Solomon Islands - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- "Solomon Islands - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- "Tuvalu country profile". BBC. 24 August 2017.

- Hunter, J.A. (12 August 2002). "A Note on Relative Sea Level Rise at Funafuti, Tuvalu" (PDF). "Tuvalu" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- Patel, Samir S. (2006). "Climate science: A sinking feeling". Nature. 440 (7085): 734–6. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..734P. doi:10.1038/440734a. PMID 16598226. S2CID 1174790.

- "World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal". climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Chou, Sin Chan; de Arruda Lyra, André; Gomes, Jorge Luís; Rodriguez, Daniel Andrés; Alves Martins, Minella; Costa Resende, Nicole; da Silva Tavares, Priscila; Pereira Dereczynski, Claudine; Lopes Pilotto, Isabel; Martins, Alessandro Marques; Alves de Carvalho, Luís Felipe; Lima Onofre, José Luiz; Major, Idalécio; Penhor, Manuel; Santana, Adérito (1 May 2020). "Downscaling projections of climate change in Sao Tome and Principe Islands, Africa". Climate Dynamics. 54 (9): 4021–4042. doi:10.1007/s00382-020-05212-7. ISSN 1432-0894. S2CID 215731771.

- Costa Resende Ferreira, Nicole; Martins, Minella; da Silva Tavares, Priscila; Chan Chou, Sin; Monteiro, Armando; Gomes, Ludmila; Santana, Adérito (11 February 2021). "Assessment of crop risk due to climate change in Sao Tome and Principe". Regional Environmental Change. 21 (1): 22. doi:10.1007/s10113-021-01746-6. ISSN 1436-378X. S2CID 231886512.

- "São Tomé and Príncipe develops National Adaptation Plan for climate change | Global Adaptation Network (GAN)". www.unep.org. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- "National Day Rally 2019: Three-pronged approach for Singapore to tackle climate change". The Straits Times. Singapore. 18 August 2019.

Further reading

- Thomas, Adelle; Baptiste, April; Martyr-Koller, Rosanne; Pringle, Patrick; Rhiney, Kevon (17 October 2020). "Climate Change and Small Island Developing States". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-083355. ISSN 1543-5938.

- Betzold, Carola (1 December 2015). "Adapting to climate change in small island developing states". Climatic Change. 133 (3): 481–489. Bibcode:2015ClCh..133..481B. doi:10.1007/s10584-015-1408-0. ISSN 1573-1480. S2CID 153937782.