Climbing shoe

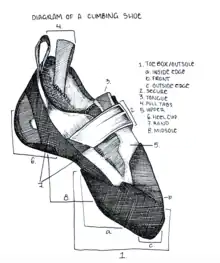

A climbing shoe is a specialized type of footwear designed for rock climbing. Typical climbing shoes have a close fit, little if any padding, and a smooth, sticky rubber sole with an extended rubber rand. Unsuited to walking and hiking, climbing shoes are typically donned at the base of a climb.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Climbing |

|---|

|

| Lists |

| Types of rock climbing |

| Types of mountaineering |

| Other types |

| Key terms |

Construction

Modern climbing shoes use carefully crafted multi-piece patterns to conform very closely to the wearer's feet. More traditional climbing shoes tend to be stiff, but modern performance oriented models are often quite soft with a flexible midsole.[2] Leather is the most common upper material, with other materials such as fabric and synthetic leather also employed.[3] The climbing rubber used for soles was developed specifically for rock-climbing.[4][5]

The nose of a shoe can be either pointed or rounded. Pointed shoes can provide the ability to stand on smaller holds more easily. Toes in rounded shoes will typically reach the front of the shoe more easily, granting them more power when pushing off the wall.[6]

Modern climbing shoes are typically subdivided into three different profiles based on their shape: neutral, moderate, and aggressive. Neutral shoes, similar to regular shoes, feature a flatter outer sole that allows your feet to rest flat while wearing them. Moderate and aggressive shoes are presented with a cambered (or curved) toe box, with aggressive shoes featuring a stronger downturn than moderate shoes.[7]

Modern climbing shoes come in different closure systems that allow the wearer to adjust the tightness of the shoe. Lace-up shoes use the traditional lace that reaches the rand of the shoe. Lace-ups allow climbers to adjust the tightness of the shoe the most. Velcro shoes will usually use have 1 or 2 Velcro straps that allow for the adjustment of tightness. Velcro allows for quicker adjustments than laced shoes, but are not as precise. Slippers don't have any form of adjustable closure, allowing the user to fit their shoes into slightly smaller spaces. They need to be fitted properly in order to prevent the feet from moving inside the shoe.[8]

Approach shoes are hybrids between light-weight hiking shoes and climbing shoes, offering some qualities of each.

Fit

Climbing shoes fit very closely to support the foot and allow the climber to use small footholds effectively. Most climbers forgo socks in order to achieve a more precise fit. Climbers will typically wear shoes in a way that sometimes uncomfortably constricts their feet.[9][10] A smaller size allows the toes to be at the front of the shoe, preventing it from shifting inside the shoe, and can allow the climber to generate more force. As a result of their tightness, most climbing shoes, particularly the more aggressive or technical styles, are uncomfortable when properly fitted.

Because pointed shoes may cause the toes to not reach the front of the shoe, this can lead to the use of smaller shoes. Depending on the material of the upper, the shoes may can stretch up to an additional two sizes, which can encourage climbers to buy shoes that are even smaller than they typically would.[6] The tight fit of climbing shoes have raised concerns about the impact on climbers' feet. Foot pain or discomfort as a result of tight shoes is a common complaint among climbers.[10][11] Given their stiff nature, the foot can be compressed while wearing climbing shoes, and chronic injuries and deformities, like hallux valgus and achilles tendinitis, can occur with long-term usage of overly-tight shoes.[2][6][10]

History

.jpg.webp)

Early rock climbers used heavy-soled mountaineering boots studded with metal cleats and hobnails. An advance on this for dry rock, were boots with Vibram soles, with a pattern of rubber studs developed by Vitale Bramani in Italy in the 1930s.[12] In postwar Britain, a new generation of climbers like Joe Brown began to climb harder routes wearing plimsolls (rubber-soled canvas sneakers),[13] sometimes with woolen socks over them to improve grip.[14] Pierre Allain was an enthusiastic French rock climber who experimented with hard composite rubber-soled canvas boots; by the late 1950s, his "PA" boots were being used by climbers worldwide. Fellow French climber Edmond Bourdonneau later introduced "EB" boots in 1950 after purchasing Pierre's company,[15] which had softer rubber soles and became very popular in the 1960 and 1970s. In 1982 Boreal, the Spanish company located in Villena, produced the "Firé" style of shoe with a revolutionary sticky rubber sole.[12]

Manufacturers

- Black Diamond Equipment

- Five Ten Footwear (owned by Adidas)

- La Sportiva

- Mammut Sports Group

- Millet

- Quechua

- Scarpa

- Tenaya

References

- Cox, Steven M. and Kris Fulsaas, ed. (September 2003). Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills (7 ed.). Seattle: The Mountaineers. ISBN 0-89886-828-9.

- Cooper, Joseph D.; Hackett, Thomas (2021), Rocha Piedade, Sérgio; Neyret, Philippe; Espregueira-Mendes, João; Cohen, Moises (eds.), "Climbing", Specific Sports-Related Injuries, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 209–220, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-66321-6_14, ISBN 978-3-030-66320-9, retrieved 2022-10-11

- "How to Choose Climbing Shoes". Athlete Audit. 6 October 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-08-19.

- "Our Climbing Shoe Rubber Comparison: Everything you need to know". 10 December 2019.

- "Vertical jump shoes". 1 October 2022.

- van der Putten, Eleonora P.; Snijders, Chris J. (2001-08-01). "Shoe design for prevention of injuries in sport climbing". Applied Ergonomics. 32 (4): 379–387. doi:10.1016/S0003-6870(01)00004-7. ISSN 0003-6870. PMID 11461039.

- Long, John (2022). How to rock climb. Bob Gaines (6th ed.). Guilford, CT. ISBN 978-1-4930-5626-2. OCLC 1256628257.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Burbach, Matt (2004). Gym climbing : maximizing your indoor experience (1st ed.). Seattle, WA: Mountaineers Books. ISBN 0-89886-742-8. OCLC 56560676.

- Schöffl, V.; Hochholzer, T.; Winkelmann, H.-P.; Strecker, W. (August 2004). "Zur Therapie von Ringbandverletzungen bei Sportkletterern". Handchirurgie · Mikrochirurgie · Plastische Chirurgie (in German). 36 (4): 231–236. doi:10.1055/s-2004-821034. ISSN 0722-1819. PMID 15368149. S2CID 260157943.

- McHenry, R.D.; Arnold, G.P.; Wang, W.; Abboud, R.J. (September 2015). "Footwear in rock climbing: Current practice". The Foot. 25 (3): 152–158. doi:10.1016/j.foot.2015.07.007. PMID 26261058.

- Killian, R. B.; Nishimoto, G. S.; Page, J. C. (1998-08-01). "Foot and ankle injuries related to rock climbing. The role of footwear". Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 88 (8): 365–374. doi:10.7547/87507315-88-8-365. ISSN 1930-8264. PMID 9735622.

- Mitchell, Peter (13 January 2011). "The History of Climbing Shoes". Livestrong.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- Kincaid, Simon. "Joe Brown: The Gritstone Legacy". Climber. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- "Putting Joes achievements into context". www.joe-brown.com. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011.

- "EB Historical EB". EB Climbing Shoes. Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

External links

![]() Media related to Climbing shoes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Climbing shoes at Wikimedia Commons