Clitoral hood

In the female human body, the clitoral hood (also called preputium clitoridis, clitoral prepuce, and clitoral foreskin)[1] is a fold of skin that surrounds and protects the glans of the clitoris; it also covers the external clitoral shaft, develops as part of the labia minora and is homologous with the foreskin (also called the prepuce) in the male reproductive system.[2][3][4] The clitoral hood is composed of mucocutaneous tissues; these tissues are between the mucous membrane and the skin, and they may have immunological importance because they may be a point of entry of mucosal vaccines.[5] The clitoral hood is also important not only in the protection of the clitoral glans, but also in pleasure, as its tissue forms part of the erogenous zones of the vulva.[5]

| Clitoral hood | |

|---|---|

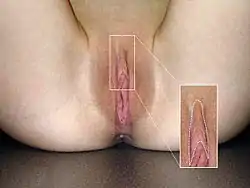

A photograph of a human vulva with outlined clitoral hood | |

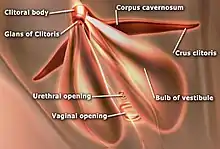

Outer anatomy of clitoris. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | preputium clitoridis |

| TA98 | A09.2.01.009 |

| TA2 | 3555 |

| FMA | 20169 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Development and variation

The clitoral hood is formed during the fetal stage by the cellular lamella.[5] The cellular lamella grows down on the dorsal side of the clitoris and is eventually fused with the clitoris. The clitoral hood is formed from the same tissues that form the foreskin in human males.

The clitoral hood varies in the size, shape, thickness, and other aesthetic aspects. Some women have large clitoral hoods that completely cover the clitoral glans. Some of these can be retracted to expose the clitoral glans, such as for hygiene purposes or for pleasure; others do not retract. Other women have smaller hoods that do not cover the full length of the clitoral glans, leaving the clitoral glans exposed all the time. Sticky bands of tissue called adhesions can form between the hood and the glans; these stick the hood onto the glans so the hood cannot be pulled back to expose the glans, and, as in the male, strongly scented smegma can accumulate.

Stimulation

Normally, the clitoral glans itself is very sensitive to be stimulated directly, such as in cases where the hood is retracted.[6] Women with hoods covering most of the clitoral glans can often masturbate by stimulating the hood over the clitoral glans; those with smaller, or more compact, structures tend to rub the clitoral glans and hood together.[6]

The clitoral hood additionally provides protection to the clitoral glans, as the foreskin does on the penile glans.[2] During sexual stimulation, the hood may also prevent the penis from coming into direct contact with the glans clitoridis, which is usually stimulated by the pressure of the partners' pubis.

Most mammals and primates approach copulation from the rear instead of the common frontal position that humans often assume, so the clitoral stimulation is directly created by glans contact with the scrotum at the base of the penis and the different contractions of its corrugated dartos muscles. The clitoral glans, like the foreskin, must be lubricated by the naturally provided sebum. If the clitoral glans is not lubricated, the hood may not properly stimulate it during sexual activity, and it may cause pain.

Modifications

In most of the world, clitoral modifications are uncommon. In some cultures, female genital mutilation (FGM) is practiced as a rite of passage into womanhood, is perceived as an improvement to the appearance of the genitalia, or is used to suppress or reduce female sexual desire and pleasure (including masturbation).[7][8][9][10] FGM was performed on many children in Western countries, including previously in the United States, to discourage masturbation and reduce diseases believed to relate to it.[11][12]

One modification that women sometimes perform of their free will is to have the hood pierced and insert jewelry, both for adornment and physical pleasure. Though less common, other women opt to have their own hood surgically trimmed or removed so as to permanently expose part or all of the clitoral glans.

See also

- Frenulum clitoridis (or crus glandis clitoridis): a frenulum surrounding the clitoris

- Preputial sheath (disambiguation)

References

- Patton, Kevin T.; Thibodeau, Gary A. (2012). Anthony's Textbook of Anatomy & Physiology - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1064. ISBN 978-0-32370-930-9. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- Sloane, Ethel (2002). Biology of Women. Cengage Learning. p. 32. ISBN 0766811425. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- Crooks, Robert; Baur, Karla (2010). Our Sexuality. Cengage Learning. p. 54. ISBN 978-0495812944. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- Mulhall, John P. (2011). John P. Mulhall; Luca Incrocci; Irwin Goldstein; Ray Rosen (eds.). Cancer and Sexual Health. Springer. pp. 13–22. ISBN 978-1-60761-915-4. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- Cold, C.J.; Taylor, T.R. (1999). "The Prepuce". British Journal of Urology. 83 (1): 34–44. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1034.x. PMID 10349413. S2CID 30559310.

- Carroll, Janell L. (2009). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. pp. 118 and 252. ISBN 978-0-495-60274-3. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

The clitoral glans is a particularly sensitive receptor and transmitter of sexual stimuli. In fact, the clitoris, although much smaller than the penis, has twice the number of nerve endings (8,000) as the penis (4,000) and has a higher concentration of nerve fibers than anywhere else on the body... In fact, most women do not enjoy direct stimulation of the glans and prefer stimulation through the [hood]... The majority of women enjoy a light caressing of the shaft of the clitoris, together with an occasional circling of the [clitoral glans], and maybe digital (finger) penetration of the vagina. Other women dislike direct stimulation and prefer to have the [clitoral glans] rolled between the lips of the labia. Some women like to have the entire area of the vulva caressed, whereas others like the caressing to be focused on the [clitoral glans].

- Link text, "Engaging Cultural Differences: The Multicultural Challenge in Liberal Democracies," Chapter 11, Schweder, et al., 2002.

- Momoh, Comfort (2005). "Female Genital Mutation". In Momoh, Comfort (ed.). Female Genital Mutilation. Radcliffe Publishing. pp. 5–12. ISBN 978-1-85775-693-7.

- Koroma, Hannah (30 September 1997). "What is Female Genital Mutilation?". Amnesty International. p. 2. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- "Female genital mutilation". World Health Organization (WHO). 2012 [2008]. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- Duffy, John (October 19, 1963). "Masturbation and Clitoridectomy: A Nineteenth-Century View". JAMA. 186 (3): 246–248. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.63710030028012. PMID 14057114.

- Rodriguez Sarah W (2008). "Rethinking the history of female circumcision and clitoridectomy: American medicine and female sexuality in the late nineteenth century". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 63 (3): 323–347. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrm044. PMID 18065832. S2CID 9234753.

External links

- "The Female Perineum: The Vulva". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016.