Clotilde von Derp

Clotilde Margarete Anna Edle von der Planitz[1] (5 November 1892 – 11 January 1974), known professionally as Clotilde von Derp, was a German expressionist dancer, an early exponent of modern dance.[2] Her career was spent essentially dancing together with her husband Alexander Sakharoff with whom she enjoyed a long-lasting relationship.[3]

Clotilde von Derp | |

|---|---|

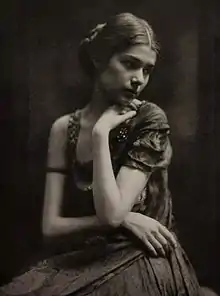

Clotilde von Derp in 1910 | |

| Born | Clotilde Margarete Anna Edle von der Planitz 5 November 1892 |

| Died | 11 January 1974 (aged 81) |

| Other names | Clotilde Sacharoff |

| Occupation | Expressionist dancer |

| Years active | 1910–1956 |

| Spouse | |

Early life

Born in Berlin, Clotilde was the daughter of Major Hans Edler von der Planitz (1863–1932) from Berlin and Margarete von Muschwitz (1868–1955). She was a member of the German lower nobility. On 25 January 1919, she married Alexander Sakharoff, a Russian dancer, teacher and choreographer.[2]

Career

As a child in Munich, Clotilde dreamt of becoming a violinist but from an early age she discovered how talented she was as a dancer. After receiving ballet lessons from Julie Bergmann and Anna Ornelli from the Munich Opera, she gave her first performance on 25 April 1910 at the Hotel Union, using the stage name Clotilde von Derp. The audience were enthralled by her striking beauty and youthful grace. Max Reinhardt presented her in the title role in his pantomime Sumurûn which proved a great success while on tour in London.[2] A photo of her by Rudolf Dührkoop was exhibited in 1913 at the Royal Photographic Society. Clotilde was a member of the radical Blaue Reiter Circle[4][5] which had been started by Wassily Kandinsky in 1911.[6]

Among her admirers were artists such as Rainer Maria Rilke and Yvan Goll. For his Swiss dance presentations, Alexej von Jawlensky gave her make-up resembling his abstract portraits. From 1913, Clotilde appeared with the Russian dancer Alexander Sacharoff with whom she moved to Switzerland during the First World War.[2] Both Sacharoff and Clotilde were known for their crossdressing costumes.[3] Clotilde's femininity was said to be accentuated by the male attire. Her costumes took on an ancient Greek look which she used in Danseuse de Delphes in 1916. Her style was said to be elegant and more modern than that achieved by Isadora Duncan. Their outrageous costumes included wigs made from silver and gold coloured metal, with hats and outfits decorated with flowers and wax fruit.[3]

The two married in 1919 and, with the financial support of Edith Rockefeller, appeared at the Metropolitan Opera in New York but without any great success.[3]

They lived in Paris until the Second World War using the name "Les Sakharoff".[2] Their 1921 poster by George Barbier to advertise their work was seen as showing a "mutually complementary androgynous couple" "united in dance" joined together in an act of "artistic creation."[4]

Sacharoff and von Derp toured widely, visiting China and Japan, which was so successful that they returned again in 1934. The couple and their extravagant costumes visited both North and South America.

von Derp and Sacharoff moved to Spain when France was invaded by Germany. They returned to South America making a new base in Buenos Aires until 1949. They toured Italy the following year and took up an invitation to teach in Rome by Guido Chigi-Saracini. They taught at the Accademia Musicale Chigiana in Siena for Saracini and they also opened their own dance school in Rome.

von Derp and Sakharoff stopped dancing together in 1956. They both continued to live in Rome until their deaths.[3] Clotilde gave and sold many of their writings and costumes, that still remained, to museums and auctions. She eventually sold the iconic 1909 painting of her husband by Alexander Jawlensky. In 1997 the German Dance Archive Cologne purchased many remaining items and they have 65 costumes, hundreds of set and costume designs and 500 photographs.[7]

Assessment

Unlike her husband, Clotilde had a taste for modern music, frequently choosing melancholic music by contemporaries such as Max Reger, Florent Schmitt and Stravinsky. Her haunting eyes and delicate smiles gave the impression she took pleasure in displaying her finely-costumed voluptuous body, even when she reached her forties. She was particularly effective in interpreting Debussy's Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune. Hans Brandenbourg maintained her ballet technique was superior to that of Alexander although he did not consider her a virtuoso. Clotilde also moved more independently of the music, dancing to the impression it created in her mind rather than to the rhythm.[3]

References

- Regarding personal names: Edle was a title before 1919, but now is regarded as part of the surname. It is translated as a noble (one). Before the August 1919 abolition of nobility as a legal class, titles preceded the full name when given (Graf Helmuth James von Moltke). Since 1919, these titles, along with any nobiliary prefix (von, zu, etc.), can be used, but are regarded as a dependent part of the surname, and thus come after any given names (Helmuth James Graf von Moltke). Titles and all dependent parts of surnames are ignored in alphabetical sorting. The masculine form is Edler.

- Frank-Manuel Peter. "Sacharoff, Clotilde (Pseudonym Clotilde von Derp, eigentlich Clotilde Margarete Anna Edle von der Planitz)". Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German). p. 323. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- Toepler, Karl (1997). Empire of Ecstasy: Nudity and Movement in German Body Culture, 1910–1935. University of California. pp. 219–222.

- Lodder, Christina; Kokkori, Maria; Mileeva, Maria (2013). Utopian reality : reconstructing culture in revolutionary Russia and beyond. Leiden: Brill. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-90-04-26322-2.

- Clotilde von Derp, National Media Museum, retrieved 18 February 2014

- Blaue Reiter, Oxford Reference, retrieved 18 February 2014

- The Sacharoffs: Two dancers within the Blaue Reiter circle, sk-kultur.de, retrieved 19 February 2014

Sources

- Brandenburg, Hans (25 February 2012). Der Moderne Tanz... Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-275-88041-2.

- Stroud, Timothy; Terraroli, Valerio (2006). The Artistic Culture Between the Wars 1920-1945: ART of the 20th Century. Rizzoli. ISBN 978-88-7624-804-7.

- Toepfer, Karl Eric (1997). Empire of Ecstasy: Nudity and Movement in German Body Culture, 1910-1935. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91827-6.

- Veroli, Patrizia; Bowlt, John E.; Sakharoff, Alexandre; Convento dei Cappuccini (Argenta, Italy) (1991). I Sakharoff, un mito della danza: fra teatro e avanguardie artistiche (in Italian). Edizioni Bora. ISBN 978-88-85345-09-6.

External links

Media related to Clothilde von Derp at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Clothilde von Derp at Wikimedia Commons