Max Reger

Johann Baptist Joseph Maximilian Reger (19 March 1873 – 11 May 1916) was a German composer, pianist, organist, conductor, and academic teacher. He worked as a concert pianist, as a musical director at the Leipzig University Church, as a professor at the Royal Conservatory in Leipzig, and as a music director at the court of Duke Georg II of Saxe-Meiningen.

Max Reger | |

|---|---|

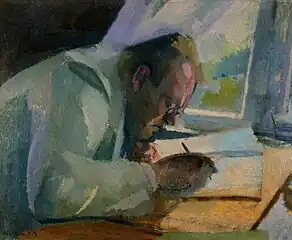

Reger at the piano, c. 1910 | |

| Born | 19 March 1873 Brand, Bavaria, German Empire |

| Died | 11 May 1916 (aged 43) Leipzig, Kingdom of Saxony, German Empire |

| Education |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Organizations | |

| Works | List of compositions |

| Spouse | Elsa Reger |

| Signature | |

.jpg.webp) | |

Reger first composed mainly Lieder, chamber music, choral music and works for piano and organ. He later turned to orchestral compositions, such as the popular Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Mozart (1914), and to works for choir and orchestra such as Gesang der Verklärten (1903), Der 100. Psalm (1909), Der Einsiedler and the Hebbel Requiem (both 1915).

Biography

Born in Brand, Bavaria, Reger was the first child of Josef Reger, a school teacher and amateur musician, and his wife Katharina Philomena. The devout Catholic family moved to Weiden in 1874. Max had only one sister, Emma, after three other siblings died in childhood. When he turned five, Reger learned organ, violin and cello from his father and piano from his mother.[1][2] From 1884 to 1889, Reger took piano and organ lessons from Adalbert Lindner, one of his father's students. During this time, he frequently acted as substitute organist for Lindner in the parish church of the city.[1] In 1886, Reger entered into the Royal Preparatory School according to his parents' wishes to prepare for a teaching profession.

In 1888, Reger was invited by his uncle Johann Baptist Ulrich to visit the Bayreuth Festival, where he heard Richard Wagner's operas Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Parsifal. This left a deep impression and made Reger decide to pursue a music career. In late summer of that year, Reger wrote his first major composition, the Overture in B minor, an unpublished work for orchestra with 120 pages. Lindner sent the score to Hugo Riemann, who replied positively but warned him against Wagner's influence and to write melodies instead of motifs.[1][3] Reger finished the preparatory school in June 1889. Also that year, he composed a Scherzo for string quartet and flute in G minor, a three movement string quartet in D minor, and a Largo for violin and piano. At his father's request, he sent the latter two works to composer Josef Rheinberger, a professor at the University of Music and Performing Arts Munich, who recognized his talents. Reger eventually sought a career in music despite his father's concerns.[1][4]

In 1890, Reger began studying music theory with Riemann in Sondershausen, then piano and theory in Wiesbaden.[5] The first compositions to which he assigned opus numbers were chamber music and Lieder. A concert pianist himself, he composed works for both piano and organ.[5] His first work for choir and piano to which he assigned an opus number was Drei Chöre (1892).

Reger returned to his parental home in Weiden due to illness in 1898, where he composed his first work for choir and orchestra, Hymne an den Gesang (Hymn to singing), Op. 21.[5] From 1899, he courted Elsa von Bercken who at first rejected him.[6] He composed many songs including the love poems Sechs Lieder, Op. 35.[7] Reger moved to Munich in September 1901, where he obtained concert offers and where his rapid rise to fame began. During his first Munich season, Reger appeared in ten concerts as an organist, chamber pianist and accompanist. Income from publishers, concerts and private teaching enabled him to marry in 1902. Because his wife Elsa was a divorced Protestant, he was excommunicated from the Catholic Church. He continued to compose without interruption, for example Gesang der Verklärten, Op. 71.[5]

In 1907, Reger was appointed musical director at the Leipzig University Church, a position he held until 1908, and professor at the Royal Conservatory in Leipzig.[5][8] In 1908 he began to compose Der 100. Psalm (The 100th Psalm), Op. 106, a setting of Psalm 100 for mixed choir and orchestra, for the 350th anniversary of Jena University. Part I was premiered on 31 July that year. Reger completed the composition in 1909, premiered in 1910 simultaneously in Chemnitz and Breslau.[9]

In 1911 Reger was appointed Hofkapellmeister (music director) at the court of Duke Georg II of Saxe-Meiningen, also taking charge of music at the Meiningen Court Theatre. He continued with his master class at the Leipzig conservatory.[5] In 1913 he composed four tone poems on paintings by Arnold Böcklin (Vier Tongedichte nach Arnold Böcklin), including Die Toteninsel (Isle of the Dead), as his Op. 128.

He gave up the court position in 1914 for health reasons. In response to World War I, already in 1914 he was planning to compose a choral work, commemorating those lost in the war. He began to set the Latin Requiem but abandoned the work as a fragment.[5] He composed eight motets as his Acht geistliche Gesänge für gemischten Chor (Eight Sacred Songs, Op. 138), embodying "a new simplicity".[10] In 1915 he moved to Jena, commuting once a week to teach in Leipzig. In Jena he composed the Hebbel Requiem for soloist, choir and orchestra.[5]

Reger died of a heart attack while staying at a hotel in Leipzig on 11 May 1916.[5][8] The proofs of Acht geistliche Gesänge, including "Der Mensch lebt und bestehet nur eine kleine Zeit", were found next to his bed.[11][12] Six years after Reger's death, his funeral urn was transferred from his home in Jena to a cemetery in Weimar. In 1930, on the wishes of Reger's widow Elsa, his remains were moved to a grave of honour in Munich Waldfriedhof.

Reger had also been active internationally as a conductor and pianist. Among his students were Joseph Haas, Sándor Jemnitz, Jaroslav Kvapil, Ruben Liljefors, Aarre Merikanto, George Szell and Cristòfor Taltabull. He was the cousin of Hans von Koessler.

Works

Reger produced an enormous output in just over 25 years, nearly always in abstract forms. His work was well known in Germany during his lifetime. Many of his works are fugues or in variation form, including the Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Mozart based on the opening theme of Mozart's Piano Sonata in A major, K. 331.

Reger wrote a large amount of music for organ, the most popular being the Benedictus from the collection Op. 59[13] and his Fantasy and Fugue on BACH, Op. 46. While a student under Hugo Riemann in Wiesbaden, Reger had already met the German organist, Karl Straube; their association as colleagues and friends began in 1898, with Straube premiering many of Reger's organ works, such as the Three chorale fantasias, Op. 52.

Reger recorded some of his works on the Welte Philharmonic organ, including excerpts from 52 Chorale Preludes, Op. 67. He also composed various secular organ works, including the Introduction, Passacaglia and Fugue, Op. 127. It was dedicated to Straube, who gave its first performance in 1913 to inaugurate the Wilhelm Sauer organ at the opening of the Breslau Centennial Hall.[14][15]

Reger was particularly attracted to the fugal form and created music in almost every genre, save for opera and the symphony (he did, however, compose a Sinfonietta, his Op. 90). A similarly firm supporter of absolute music, he saw himself as being part of the tradition of Beethoven and Brahms. His work often combined the classical structures of these composers with the extended harmonies of Liszt and Wagner, to which he added the complex counterpoint of Bach. Reger's organ music, though also influenced by Liszt, was provoked by that tradition.

Some of the works for solo string instruments turn up often on recordings, though less regularly in recitals. His solo piano and two-piano music places him as a successor to Brahms in the central German tradition. He pursued intensively Brahms's continuous development and free modulation, whilst being rooted in Bach-influenced polyphony.

Reger was a prolific writer of vocal works, Lieder, works for mixed chorus, men's chorus and female chorus, and extended choral works with orchestra such as Der 100. Psalm and Requiem, a setting of a poem by Friedrich Hebbel, which Reger dedicated to the soldiers of World War I. He composed music to texts by poets such as Gabriele D'Annunzio, Otto Julius Bierbaum, Adelbert von Chamisso, Joseph von Eichendorff, Emanuel Geibel, Friedrich Hebbel, Nikolaus Lenau, Detlev von Liliencron, Friedrich Rückert and Ludwig Uhland. Reger assigned opus numbers to major works himself.[5]

His works could be considered retrospective as they followed classical and baroque compositional techniques such as fugue and continuo. The influence of the latter can be heard in his chamber works which are deeply reflective and unconventional.

Reception

In 1898 Caesar Hochstetter, an arranger, composer and critic, published an article entitled "Noch einmal Max Reger" ("Max Reger once again") in a music magazine (Die redenden Künste 5 no. 49, pp. 943 f). Caesar recommended Reger as "a highly talented young composer" to the publishers. Reger thanked Hochstetter with the dedications of his piano pieces Aquarellen, Op. 25, and Cinq Pièces pittoresques, Op. 34.[5]

Reger had an acrimonious relationship with Rudolf Louis, the music critic of the Münchener Neueste Nachrichten, who usually had negative opinions of his compositions. After the first performance of the Sinfonietta in A major, Op. 90, on 2 February 1906, Louis wrote a typically negative review on 7 February. Reger wrote back to him: "Ich sitze in dem kleinsten Zimmer in meinem Hause. Ich habe Ihre Kritik vor mir. Im nächsten Augenblick wird sie hinter mir sein!" ("I am sitting in the smallest room of my house. I have your review before me. In a moment it will be behind me!").[16][17] Another source has the German composer Sigfrid Karg-Elert as the targeted critic of this letter.[18]

Arnold Schoenberg was an admirer of Reger's. A letter he sent to Alexander von Zemlinsky in 1922 states: "Reger...must in my view be done often; 1, because he has written a lot; 2, because he is already dead and people are still not clear about him. (I consider him a genius.)"[19]

Films

The documentary Max Reger – Music as a perpetual state, by Andreas Pichler and Ewald Kontschieder, Miramonte Film, was released in 2002. It was the first factually based film documentation about Max Reger. It was produced in cooperation with the Max-Reger-Institute.[20]

Max Reger: The Last Giant, a documentary film about the life and works of Max Reger, is included on a 6 DVD set entitled Maximum Reger released in December 2016 to mark the 100th anniversary of Reger's death. The set was produced by Fugue State Films and in addition to the documentary includes excerpts from Reger's most important works for orchestra, piano, chamber ensemble and organ, with performances by Frauke May, Bernhard Haas, Bernhard Buttmann and the Brandenburgisches Staatsorchester Frankfurt.[21]

References

- "Lebenslauf". Max Reger Institute (in German).

- Stein, Fritz (1939). Max Reger. Potsdam: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Athenaion.

- Lindner, Adalbert (1922). Max Reger: Ein Bild seines Jugendlebens und künstlerischen Werdens. Stuttgart: J. Engelhorns Nachfolger.

- Popp, Susanne; Shigihara, Susanne (1988). At the Turning Point to Modernism. Bonn: Bouvier Verlag Herbert Grundmann.

- Biography 2012.

- Lux 1963.

- SWR 2016.

- Schröder 1990.

- Op106 2016.

- Op138 2016.

- Krumbiegel 2014.

- Brock-Reger 1953.

- Anderson, Christopher S. 2013. Twentieth-Century Organ Music. Routledge. p. 123. ISBN 0-203-14223-3

- Mühle 2015.

- Biography 1913 2016.

- Slonimsky 1965.

- Kirshnit 2006.

- Schonberg, Harold (2 December 1973). "Nobody Wants To Play Max Reger". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Schonberg, Harold C. (2 December 1973). "Nobody Wants To Play Max Reger". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Muspilli 2016.

- "Maximum Reger". Fugue State Films. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

Bibliography

- Albright, Daniel, ed. (2004), Modernism and music: an anthology of sources. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-01266-2.

- Anderson, Christopher (2003). Max Reger and Karl Straube: Perspectives on an Organ Performing Tradition. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-3075-7.

- Bittmann, Antonius (2004). Max Reger and Historicist Modernisms. Baden-Baden: Koerner. ISBN 3-87320-595-5.

- Bloesch-Stöcker, Adele (1973). Erinnerungen an Max Reger. Bern: H. Bloesch.

- Brock-Reger, Charlotte (1953). "Mein Vater Max Reger". Die Zeit (in German). Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- Cadenbach, Rainer (1991). Max Reger und Seine Zeit. Laaber: Laaber-Verlag. ISBN 3-89007-140-6.

- Grim, William (1988). Max Reger: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-25311-0.

- Häfner, Roland (1982). Max Reger, Klarinettenquintett op. 146. Munich: W. Fink Verlag. ISBN 3-7705-1973-6.

- Kirshnit, Fred (2006). "Max Reger, Psalm 100, Op. 106". American Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- Krumbiegel, Martin (2014). Sichardt, Martina (ed.). Von der Kunst der Beschränkung / Aufführungspraktische Überlegungen zu Max Regers "Der Mensch lebt und bestehet nur eine kleine Zeit", op. 138, Nr. 1. pp. 231–243. ISBN 978-3-487-15145-8.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

- Lux, Antonius, ed. (1963). Große Frauen der Weltgeschichte. Tausend Biographien in Wort und Bild (in German). Munich: Sebastian Lux Verlag. p. 386.

- Mead, Andrew (2004). "Listening to Reger". The Musical Quarterly 87, no. 4 (Winter): 681–707.

- Mercier, Richard (2008). The Songs of Max Reger: A Guide and Study. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6120-6.

- Reger, Elsa von Bagenski (1930). Mein Leben mit und für Max Reger: Erinnerungen von Elsa Reger. Leipzig: Koehler & Amelang.

- Reger, Max (2006). Selected Writings of Max Reger, edited and translated by Christopher Anderson. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97382-1.

- Schreiber, Ottmar, and Ingeborg Schreiber (1981). Max Reger in seinen Konzerten, 3 vols. Veröffentlichungen des Max-Reger-Institutes (Elsa-Reger-Stiftung) 7. Bonn: Dümmler. ISBN 3-427-86271-2.

- Schröder, Heribert (1990). "Acht geistliche Gesänge / op. 138" (PDF). Carus-Verlag. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- Slonimsky, Nicolas (1965). Lexicon of Musical Invective (2 ed.). New York: Coleman-Ross. ISBN 978-0-393-32009-1.

- Mühle, Eduard (2015). Breslau: Geschichte einer europäischen Metropole (in German). Cologne, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag. p. 201. ISBN 978-3-41-250137-2.

- Williamson, John (2001). "Reger, (Johann Baptist Joseph) Max(imilian)". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- "Max Reger Curriculum vitae". Max-Reger-Institute. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- "1913". Max-Reger-Institute. 2016.

- "Max Reger's works" (in German). Max-Reger-Institute / Elsa-Reger-Stiftung. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- "Der 100. Psalm Op. 106" (in German). Max-Reger-Institute / Elsa-Reger-Stiftung. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- "Reger: Acht geistliche Gesänge op. 138 (Carus Classics)". Carus-Verlag. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- "Max Reger – Music As A Perpetual State". muspillo.it. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- "Max-Reger-Institut in Karlsruhe / "Neue Fülle"" (in German). SWR. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

Further reading

- Special Issue on Max Reger – The Musical Quarterly, Volume 87, Issue 4

- Brauss, Helmut, (1994), Max Reger's Music For Solo Piano. University of Alberta Press. ISBN 0-88864-255-5

External links

- Free scores by Max Reger at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Max Reger Portrait at RAI Radio

- Free scores by Max Reger in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Max Reger: Werkausgabe Carus-Verlag

- The Mutopia Project has compositions by Max Reger

- Works by or about Max Reger at Internet Archive

- Aus der Jugendzeit Op. 17 at University of Toronto Robarts Library

- The Max Reger Foundation of America, New York City

- Max Reger Archive Meiningen (in German)

- Piano recital without Pianist or Max Reger plays Max Reger

- Max Reger zum 100. Todestag MDR

- The portal for the Reger-year 2016 reger2016.de

- Jürgen Schaarwächter: Monumental verinnerlicht / Zwischen Romantik und Moderne: Max Regers Bedeutung für die evangelische Kirchenmusik (in German) zeitzeichen.net