Coal mining in the United States

Coal mining is an industry in transition in the United States. Production in 2019 was down 40% from the peak production of 1,171.8 million short tons (1,063 million metric tons) in 2008. Employment of 43,000 coal miners is down from a peak of 883,000 in 1923.[1] Generation of electricity is the largest user of coal, being used to produce 50% of electric power in 2005 and 27% in 2018.[2] The U.S. is a net exporter of coal. U.S. coal exports, for which Europe is the largest customer, peaked in 2012.[3] In 2015, the U.S. exported 7.0 percent of mined coal.[4]

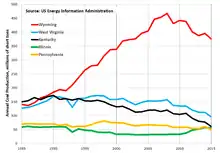

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), in 2015, Wyoming, West Virginia, Kentucky, Illinois, and Pennsylvania produced about 639 million short tons (580 million metric tons), representing 71% of total coal production in the United States.[5]

In 2015, four publicly traded U.S. coal companies filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, including Patriot Coal Corporation, Walter Energy, and the fourth-largest Alpha Natural Resources. By January 2016, more than 25% of coal production was in bankruptcy in the United States[6] including the top two producers Peabody Energy[7][8] and Arch Coal.[6][9] When Arch Coal filed for bankruptcy protection, the price of coal had dropped 50% since 2011[10] and it was $4.5 billion in debt.[6][10] On October 5, 2016, Arch Coal emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.[11] In October 2018, Westmoreland Coal Company filed for bankruptcy protection.[12][13][14] On May 10, 2019, the third largest U.S. coal company by production, Cloud Peak Energy, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.[15] On October 29, 2019 Murray Energy filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.[16]

History

Coal, primarily from underground mines east of the Mississippi was the nation's primary fuel source until the early 1950s. Surface (strip) and mountaintop removal mining overtook underground mines in the 1970s. In 2000, the majority of coal was produced west of the Mississippi.

Production

_(cropped).png.webp)

In 2018, coal mining decreased to 755 million short tons, and American coal consumption reached its lowest point in nearly 40 years.[17] In 2017, U.S. coal mining had increased to 775 million short tons.[3] In 2016, US coal mining declined to 728.2 million short tons, down 37 percent from the peak production of 1,172 million tons in 2008. In 2015, 896.9 million short tons of coal were mined in the United States,[18] with an average price of $31.83 per short ton,[19] worth $28.6 billion.[20][21]

| Coal in the US (million short tons)[lower-alpha 1] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Production[22][23] | Net exports[24][25][26] | Net available | |

| 2000 | 1,074 | 46 | 1,008 |

| 2001 | 1,128 | 29 | 1,099 |

| 2002 | 1,094 | 23 | 1,071 |

| 2003 | 1,072 | 18 | 1,054 |

| 2004 | 1,112 | 21 | 1,091 |

| 2005 | 1,131 | 19 | 1,112 |

| 2006 | 1,163 | 13 | 1,150 |

| 2007 | 1,147 | 23 | 1,124 |

| 2008 | 1,172 | 47 | 1,125 |

| 2009 | 1,075 | 36 | 1,039 |

| 2010 | 1,084 | 62 | 1,022 |

| 2011 | 1,096 | 94 | 1,002 |

| 2012 | 1,016 | 117 | 899 |

| 2013 | 985 | 109 | 876 |

| 2014 | 1,000 | 86 | 914 |

| 2015 | 896 | 63 | 833 |

| 2016 | 739 | 51 | 688 |

| 2017 | 775 | 97 | 678 |

| 2018 | 755 | 116 | 678 |

| 2019[27] | 705 | 93 | 612 |

Coal production by region

.png.webp)

The three regions producing the largest amount of coal are Powder River Basin of Wyoming and Montana, the Appalachian Basin and the Illinois Basin. In the United States, coal production declined from 2008 but the decline was unevenly distributed. Production from the largest coal mining-region in the U.S., the Powder River Basin, with most of the coal buried too deeply to be economically accessible,[28] declined 16 percent, the Appalachian Basin declined 32 percent 2008 to 2014 and the Illinois Basin increased its production 39 percent from 2008 to 2014.[29] In 2015, five states—Wyoming, West Virginia, Kentucky, Illinois, and Pennsylvania—produced almost 3/4 of all coal production nationwide. Wyoming produced 375.8 million short tons representing 42% of U. S. coal production, West Virginia produced 95.6 million short tons or 11%, Kentucky was third with 61.4 or 7%, Illinois was fourth with 56.1 or 6% and Pennsylvania was fifth with 50.0 or 6%.[5]

As of 2014, twenty-five states produced coal. The coal-producing states were, in descending order, with annual production in millions of short tons:[30]

| 2014 to 2018 US coal production (million short tons) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | State | 2014 | 2018 | % Change | Notes |

| 1 | Wyoming | 395.7 | 304.2 | -23% | (see Coal mining in Wyoming) |

| 2 | West Virginia | 112.2 | 95.4 | -15% | |

| 3 | Pennsylvania | 60.9 | 49.9 | -18% | |

| 4 | Illinois | 58 | 49.6 | -14% | (see Illinois#Coal) |

| 5 | Kentucky | 77.3 | 39.6 | -49% | (see Coal mining in Kentucky) |

| 6 | Montana | 44.6 | 38.6 | -13% | |

| 7 | Indiana | 39.3 | 34.6 | -12% | |

| 8 | North Dakota | 29.2 | 29.6 | 1% | |

| 9 | Texas | 43.7 | 24.8 | -43% | |

| 10 | Alabama | 16.4 | 14.8 | -10% | |

| 11 | Colorado | 24 | 14 | -42% | (see Coal mining in Colorado) |

| 12 | Utah | 17.9 | 13.6 | -24% | |

| 13 | Virginia | 15.1 | 12.7 | -16% | |

| 14 | New Mexico | 22 | 10.8 | -51% | |

| 15 | Ohio | 22.3 | 9 | -60% | |

| 16 | Arizona | 8.1 | 6.6 | -19% | |

| 17 | Mississippi | 3.7 | 2.9 | -22% | |

| 18 | Louisiana | 2.6 | 1.5 | -42% | |

| 19 | Maryland | 2 | 1.3 | -35% | |

| 20 | Alaska | 1.5 | 0.9 | -40% | |

| 21 | Oklahoma | 0.9 | 0.6 | -33% | |

| 22 | Missouri | 0.4 | 0.3 | -25% | |

| 23 | Tennessee | 0.8 | 0.2 | -75% | |

| 24 | Arkansas | 0.1 | 0 | -100% | |

| 25 | Kansas | 0.1 | 0 | -100% | |

| US Total | 998.8 | 755.5 | -24% | ||

Coal production by type

The hardest coal, anthracite, originally used for steel production, heating, and as fuel for ships and railroads, had by 2000 dwindled to an insignificant portion of production. Softer bituminous coal replaced anthracite for steel production. The even softer sub-bituminous and lignite coals overtook bituminous for power generation in the 2000s.

Companies

| # | Company | M short tons | % of US | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Peabody Energy | 155.5 | 20.6% | Chapter 11 bankruptcy 2016, exited 2017[31] |

| 2 | Arch Coal | 100.3 | 13.3% | Chapter 11 bankruptcy 2016, exited 2016[32] |

| 3 | Cloud Peak Energy | 49.5 | 6.6% | Chapter 11 bankruptcy October 5, 2019[33][34] |

| 4 | Murray Energy | 46.4 | 6.1% | Chapter 11 bankruptcy Oct 2019[35] |

| 5 | Alliance Resource | 40.3 | 5.3% | Downgraded to BB status April 2021[36] |

| 6 | Revelation/Blackjewel | 38.5 | 5.1% | Chapter 11 Bankruptcy July 2019[37] |

| 7 | NACCO Industries | 37.3 | 4.9% | |

| 8 | CONSOL Energy | 27.6 | 3.6% | Murray Energy took controlling stake in 2013[38] |

| 9 | Foresight Energy | 23.3 | 3.1% | Filed Chapter 11 Bankruptcy March 2020[39] |

| 10 | Contura Energy | 22.8 | 3.0% | |

| 11 | Kiewit | 18.5 | 2.4% | |

| 12 | Westmoreland Coal | 14.8 | 2.0% | Chapter 11 bankruptcy 2018, exited March 15, 2019[40][41] |

| 13 | Vistra Energy | 14.0 | 1.8% | |

| 14 | Blackhawk Mining | 13.3 | 1.8% | Chapter 11 Bankruptcy July 19, 2019[42] |

| 15 | Wolverine Fuels | 9.1 | 1.2% | |

| 16 | Coronado Coal | 8.5 | 1.1% | |

| 17 | Warrior Met | 7.7 | 1.0% | |

| 18 | Hallador Energy | 7.6 | 1.0% | |

| 19 | Global Mining | 7.6 | 1.0% | |

| 20 | Prairie State | 6.3 | 0.8% | |

| 21 | Western Fuels | 6.3 | 0.8% | |

| 22 | White Stallion | 5.6 | 0.7% | Chapter 11 Bankruptcy, December 2, 2020; |

| 23 | J Clifford Forrest | 5.2 | 0.7% |

In 2018, the production owned by the top ten companies was 71.6% of total US coal production.[45]

In 2018, the production owned by the top 23 companies was 87.9% of the total US coal production.[45]

Coal mining employment

At the end of July 2022, the coal industry employed approximately 38,400 miners.[1]

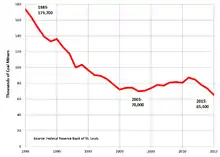

US employment in coal mining peaked in 1923, when there were 863,000 coal miners.[46] Since then, mechanization has greatly improved productivity in coal mining, so that employment has declined at the same time coal production increased. The average number of coal mining employees declined to 41,600 in 2020.[1] This was below the previous low of 70,000 in 2003, and the lowest number of US coal miners in at least 125 years.[47][48]

Because of the sharp declines in the U.S. coal industry, the Harvard Business Review discussed retraining coal workers for solar photovoltaic employment because of the rapid rise in U.S. solar jobs.[49] A recent study indicated that this was technically possible and would account for only 5% of the industrial revenue from a single year to provide coal workers with job security in the energy industry as whole.[50]

Exports

The U.S. is a net exporter of coal.[51] US net coal exports increased ninefold from 2006 to 2012, peaked at 117 million short tons in 2012, and were 97 million short tons in 2017.[3] In 2015, 60% of net US exports went to Europe, 27% to Asia.[52] The largest individual country export markets were the Netherlands (12.9 million short tons), India (6.4 million short tons), Brazil (6.3 million short tons), and South Korea (6.1 million short tons). Coal exports to China, formerly one of the major markets, declined from 8.3 million short tons in 2013, down to 0.2 million tons in 2015.[25][53]

In 2012, six coal export terminals were in the planning stages in the Pacific Northwest.[54] They were scheduled to be supplied by strip mines in the Powder River Basin. The export markets were South Korea, Japan, China, and other Asian nations. Like the Keystone Pipeline the building of the terminals raised environmental concerns with respect to global warming.[55] As of February 2016, four proposals for coal terminals had been withdrawn, leaving two still applied for. The withdrawals were ascribed to loss of demand and consequent lower coal prices.[56]

Usage

In 2013, 92.8 percent of US internal coal consumption was for electricity generation. Other uses were industrial (4.7 percent), coke manufacture (2.3 percent), and commercial and institutional (0.2 percent).[57][58] In 2016, the EIA calculated that coal would provide 30% of electricity generation nationwide with natural gas providing 34%, nuclear, 19%, and renewables, 15%.[59]

Both the tonnage of coal used for electricity (1047 million short tons) and the amount of US electricity generated from coal (2020 TWh) peaked in 2007. By 2015, electrical generation from coal had declined to 1360 TWh and 966 TWh in 2019, as coal's share of total electrical generation in the US fell from 48.5 percent in 2007, to 33.1 percent in 2015, to 23 percent in 2019, and 19% in 2020.[60] Most of the decrease in coal electricity was offset by an increase in generation from natural gas-fired power plants.[61][62][63]

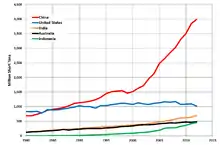

In 2006, there were 1493 coal-powered generating units at electrical utilities across the US, with total nominal capacity of 335.8 GW[64] (compared to 1024 units at nominal capacity of 278 GW in 2000).[65] Actual power generated from coal in 2006 was 227.1 GW (1991 TWh per year),[66] the highest in the world and still slightly ahead of China (1950 TWh per year) at that time. In 2000, US production of electricity from coal was 224.3 GW (1966 TWh per year).[66] In 2006, the US consumed 1,027 million short tons (932 million metric tons) or 92.3% of coal mined for electricity generation.[67]

As of 2013, domestic coal consumption for power production was being displaced by natural gas, but production from strip mines utilizing thick deposits in the western United States such as the Powder River Basin in northern Wyoming and Southern Montana for export to Asia increased.[68] In 2014, 3.0 percent of the coal shipments from Montana and Wyoming were exported.[69] The 2014 coal exports from the two states of 13.4 million short tons represented an increase of 1.2 million tons over 2012 export levels, which is 0.3 percent of the states’ 2014 total coal shipments of 439.8 million short tons (399 million metric tons).[70]

Coal mining on federal lands

As of 2013, 41 percent of US coal production was mined from federal land, almost all of it in the western US, where federal coal makes up about 80 percent of mined production. The federal coal program is overseen by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) under the US Department of Interior. Federal coal lands are leased by competitive sealed bids, for the highest bonus (initial payment) offered. In addition, the government receives an annual rental of $3 per acre, and a fixed percentage royalty of the market value of coal produced. The royalty is 8 percent for underground mines and 12.5 percent for surface mines.[71] In 2014, the program generated about $1.2 billion in lease bonuses, rentals, and royalties for coal mining on federal lands.[48]

In January 2016, the Obama administration announced a three-year moratorium on federal coal lease sales on public land, effective immediately, and leaving around 20 years-of coal production under way. He noted that the program had not had a "top-down review" for the past 30 years.[72] This would affect 50 licenses.[21] The Trump administration reversed the moratorium.[73]

The Government Accountability Office has questioned whether bonus and royalty rates reflect coal's market value. Per GAO, since 1990 Colorado earned about $22 million less from bonus bids than Utah, though Colorado leased out almost 76 million tons more coal than Utah. BLM personnel noted that the coal mined in Utah was closer to its market, and so was more valuable due to lower transportation cost.[71]: 27

The GAO report noted that the BLM publishes little information on federal coal lease sales, also does not include their appraisal report, because some of this information is "sensitive and proprietary"; this violates BLM's own guidance.[71]: 44

The GAO also noted that the competitiveness of federal coal lease sales was limited by lack of multiple bids. Of the 107 tracts leased since 1990, 96 drew only a single bidder. This was attributed to the fact that most leased tracts were close to a single existing mine, and the large capital cost of installing a new mine discouraged competition. The BLM can reject bids which do not meet its estimate of fair market value, and 18 of the coal tracts leased since 1990 were tracts re-bid after the BLM had rejected the initial bids as too low. However, the GAO found that some BLM offices did not have the personnel to prepare adequate estimates of market value.[71]: 16–19

A Boston-based think tank, the Institute for Energy Economic & Financial Analysis study estimated that, since 1991, $29 billion over a 30-year period was lost in the Powder River Basin, due to lack of competitive bidding.[74][75] The institute's mission statement notes that its goals include: “… to reduce dependence on coal and other non-renewable energy resources.”[76]

Energy value

The average heat content of mined US coal has declined over the years as higher-rank coal production (anthracite, and then bituminous coal) declined, and production of lower rank coal (Sub-bituminous and lignite) increased. The average heat content of US-mined coal decreased 21% from 1950 to 2016, and 6.8% in the 20 years from 1996 to 2016.[77]

The tonnage of mined coal hit a peak in 2008, and has declined since. The energy value of mined US coal hit its all-time peak a decade earlier, in 1998, at 26.2 quadrillion BTU. The energy value of US coal mined in 2016 was 14.6 quadrillion BTU, 44 percent lower than the peak.[78]

| Year | Million short tons[22][23] | Million BTU/short ton[77] | Quadrillion BTU[79] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 1,074 | 21.07 | 22.74 |

| 2001 | 1,128 | 20.77 | 23.55 |

| 2002 | 1,094 | 20.67 | 22.73 |

| 2003 | 1,072 | 20.50 | 22.09 |

| 2004 | 1,112 | 20.42 | 22.85 |

| 2005 | 1,131 | 20.35 | 23.18 |

| 2006 | 1,163 | 20.31 | 23.79 |

| 2007 | 1,147 | 20.34 | 23.49 |

| 2008 | 1,172 | 20.21 | 23.85 |

| 2009 | 1,075 | 19.96 | 21.62 |

| 2010 | 1,084 | 20.17 | 22.04 |

| 2011 | 1,096 | 20.14 | 22.04 |

| 2012 | 1,016 | 20.22 | 20.68 |

| 2013 | 985 | 20.18 | 20.00 |

| 2014 | 1,000 | 20.15 | 20.29 |

| 2015 | 897 | 19.88 | 17.95 |

| 2016 | 728 | 19.88 | 14.58 |

| 2017 | 774 | 19.78 | 16.00 |

| 36.68 million BTU = 1 tonne of oil equivalent (toe) | |||

Accidents

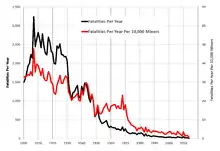

Mine disasters have still occurred in recent years in the US,[80] Examples include the Sago Mine disaster of 2006, and the 2007 mine accident in Utah's Crandall Canyon Mine, where nine miners were killed and six entombed.[81] In the decade 2005–2014, US coal mining fatalities averaged 28 per year.[46] The most fatalities during the 2005–2014 decade were 48 in 2010, the year of the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster in West Virginia, which killed 29 miners.[82]

Human and environmental health

Accidents are not the only threat to modern coal miners and those living in coal regions. Respiratory disorders from coal dust and heart disease are both prevalent, especially in the West Virginia Appalachian coal mining region.[83] When mountaintop removal mining is used, not only do the miners suffer, but people living in the regions develop health issues. Excess rock, also known as overburden, removed from the mountains is dumped into valleys creating toxic runoff, that often pollutes streams used for local water sources or even the groundwater and wells.[83] Flooding and air pollution is also common in mining regions.[84] Burning coal releases CO2 into the atmosphere which is contributing to global climate change.

In addition to the respiratory and cardiac illnesses that remain a threat to coal miners, these individuals are also at risk for mental health related issues. While short term, coal extraction companies can create more jobs within communities and increase capital investment, research has shown that these heavily coal dependent communities have suffered when it comes to their mental and emotional health. According to the Gallup-Healthways Index, in the years 2009 and 2010, West Virginia, one of the top contributors of coal in the United States, ranked last in "Physical Health," “Emotional Health," “Life Evaluation," as well as "Overall Well-Being." On top of that, it was also found that individuals who were closely involved or located near mountaintop removal sites were more at risk for higher mortality rates, developing life-threatening diseases, and total poverty than those who extracted coal underground.[85]

Adverse economic impacts

Critics of coal mining in West Virginia sometimes refer to the mine locations as energy sacrifice zones,[86] being loosely defined as areas where the health of the people and the environment has been sacrificed for the energy, jobs and profits that can be derived from the activity.

Because of the poor economy in the region, coal mining is many miners' only economic option.[83]

While data can be misleading about the creation of jobs in mining regions, The authors, Perdue and Pavela, of "Addictive Economies and Coal Dependency," highlight the fact that communities with no mining had lower levels of poverty than the communities with mining. Perdue and Pavela blamed this on the fact that "dependency on natural resources resulted in stifled development and negative socioeconomic outcomes." According to the article, West Virginia is one of the top producers of coal. Regardless, West Virginia only contributed 7% to the gross product.[85]

Opposition

Concern about global warming in the US[87] – especially in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and Al Gore's receipt of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for his raising awareness of climate change – temporarily increased public opposition to new coal-fired power plants.[88][89] Simultaneously with these events, the anti-coal movement in the US – similar to that in the UK and Australia – had made coal-fired power projects more politically costly, and spurred further shifts in public opinion against coal-fired power.[90][91][92]

In a 2004 effort to foster positive public opinion of coal, many large coal mining companies, electric utilities, and railroads in the U.S. launched a high-profile marketing campaign to convince the American public that coal-fired power can be environmentally sustainable, despite the fact that coal is the largest contributor of CO2 emissions in the electricity sector.[93][94][95] However, some environmentalists condemned this campaign as a "greenwashing" attempt to use environmentalist rhetoric to disguise what they call "the inherently environmentally unsustainable nature of coal-fired power generation".[96]

Reserves

The United States has 477 billion tons of demonstrable reserves.[97] The energy content of this coal exceeds that of the country's oil and gas reserves.

See also

- List of coal mines in the United States

- American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity

- Coal pollution mitigation

- Coal mining

- Coal power in the United States

- Environmental effects of coal

- Greenhouse gas emissions by the United States

- History of coal mining in the United States

- Coal Creek War

- List of the largest coal power stations in the United States

Notes

- 1 short ton = 0.907184 metric tonnes

Footnotes

- Total employment: coal mining, Federal Reserve Board of St. Louis. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- "EIA – Electricity Data". eia.gov. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- "U.S. coal exports increased by 61% in 2017 as exports to Asia more than doubled – Today in Energy – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". eia.gov.

- U.S. coal exports fall on lower European demand, increased global supply, US Energy Information Administration, October 3, 2014.

- Which states produce the most coal?, EIA, February 28, 2017, retrieved May 9, 2016

- Tracy Rucinski (January 10, 2016). "Arch Coal files for bankruptcy, hit by mining downturn". Reuters.

- "Peabody Energy Chapter 11 Petition" (PDF). PacerMonitor. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- "Top coal miner Peabody files for bankruptcy". The Sydney Morning Herald. April 13, 2016.

- Matthew Brown; Mead Gruver (March 28, 2017), "How Trump's executive order will affect coal industry", Billings Gazette, Associated Press, retrieved March 28, 2017

- John W. Miller; Peg Brickley (January 11, 2016), "Arch Coal files for Bankruptcy", The Wall Street Journal

- Chaney, Sarah (October 5, 2016). "Arch Coal Emerges from Chapter 11". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- "Westmoreland Enters into Restructuring Support Agreement with Members of Ad Hoc Lending Group; WMLP Simultaneously Files Chapter 11 to Sell Assets". westmoreland.com. Westmoreland Coal Company. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Kilgore, Tomi (October 9, 2018). "Coal producer Westmoreland Resource Partners files for bankruptcy". MarketWatch. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Westmoreland Coal Company files for bankruptcy protection". Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Third-Biggest U.S. Coal Company Files for Bankruptcy". Flathead Beacon. May 10, 2019. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- "Murray Energy News: Coal Miner Goes Bust as Trump Rescue Fails". Bloomberg.com. October 29, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- "In 2018, U.S. coal production declined as exports and Appalachian region prices rose – Today in Energy – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". eia.gov.

- US Energy Information Administration, Table 1 Coal Production, Annual Coal Report, 2015.

- US Energy Information Administration, Table 28, Average Price of Coal, Annual Coal Report, 2015.

- Annual Coal Report, U.S. Department of Energy, November 3, 2016, retrieved March 28, 2017

- Oliver Milman Obama administration halts new coal mining leases on public land The Guardian, January 15, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016

- Annual coal production, US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved Apr. 2016.

- Quarterly coal production, US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved Apr. 2016.

- Quarterly coal exports, US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved Apr. 2016.

- Quarterly coal exports, US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved Apr. 2016.

- Coal exports and imports, US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved Apr. 2016.

- Quarterly Coal Report October–December 2019 (PDF). U.S. Energy Information Administration. 2020.

- Inventory of Assessed Federal Coal Resources and Restrictions to Their Development (PDF) (Report). U.S. Departments of Energy, Interior and Agriculture. August 2007. p. 94. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- Coal browser, US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- Coal data browser, US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- "Peabody – Newsroom". Peabodyenergy.com. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Chaney, Sarah (October 5, 2016). "Arch Coal Emerges from Chapter 11". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- Cooper McKim (May 10, 2019), Cloud Peak Energy Voluntarily Files For Bankruptcy, Wyoming Public Media

- "Case number: 1:19-bk-11047 – Cloud Peak Energy Inc. – Delaware Bankruptcy Court". inforuptcy.com. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- "Murray Energy joins growing list of coal companies to declare bankruptcy". CNBC. October 29, 2019.

- https://www.fitchratings.com/research/corporate-finance/fitch-downgrades-alliance-resource-partners-idr-to-bb-outlook-remains-negative-08-04-2021

- "Seven Bombshells in the Blackjewel Bankruptcy". July 9, 2019.

- "POLITICO Pro".

- "Foresight Energy is latest U.S. Coal miner in bankruptcy".

- Robert Walton (October 10, 2018). "Westmoreland Chapter 11 marks 4th major US coal company to declare bankruptcy". Utility Dive. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- Proctor, Darrell (March 17, 2019). "Westmoreland Coal Emerges from Chapter 11 Bankruptcy". POWER Magazine. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- "Prime Clerk". cases.primeclerk.com. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- Endale, Brook. "White Stallion Energy files for bankruptcy, terminates all 260 employees". Evansville Courier & Press. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- Proctor, Darrell (December 4, 2020). "Continued Toll on Coal; More Companies File Bankruptcy". POWER Magazine. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- "Major U.S. Coal Producers, 2018" (PDF). U.S. Energy Information Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2019.

- "Coal Fatalities for 1900 Through 2014". US Mine Safety and Health Administration. Archived from the original on April 19, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- Historical Statistics of the United States, US Department of Commerce, 1960, p.358-359.

- Coral Davenport (January 14, 2016). "In Climate Move, Obama Halts New Coal Mining Leases on Public Lands". The New York Times.

- Joshua M. Pearce (August 8, 2016). "What If All U.S. Coal Workers Were Retrained to Work in Solar?". Harvard Business Review.

- Edward P. Louie; Joshua M. Pearce (2016). "Retraining Investment for U.S. Transition from Coal to Solar Photovoltaic Employment". Energy Economics. 57: 295–302. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2016.05.016.

- "Quarterly Coal Report – Energy Information Administration". eia.gov.

- "US COAL – High GCV Coal". uscoal.in. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- Coal prices and production decline in 2015, US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved Apr. 2016.

- "Coal Scorecard: Your Guide To Coal In The Northwest". EarthFix Oregon Public Broadcasting. June 28, 2012. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Phuong Le (March 25, 2013). "NW governors ask White House to exam coal exports". The San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- "What coal's decline means for Northwest export markets," Oregon Public Broadcasting, February 17, 2016.

- "Pittsburghlive.com". Archived from the original on September 11, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

- US Energy Information Administration: Net generation by energy source. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- Natural gas-fired electricity generation expected to reach record level in 2016, EIA, July 14, 2016, retrieved March 28, 2017

- "Electricity in the U.S. – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)".

- Coal: Consumption for electricity generation, US Energy Information Administration, April 16, 2016.

- Net generation by energy source, US Energy Information Administration, April 4, 2016.

- "Electricity in the U.S. – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". eia.gov. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- "Existing Electric Generating Units in the United States". Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- "Inventory of Electric Utility Power Plants in the United States 2000". Energy Information Administration. March 2002. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- "Electric Power Annual with data for 2006". Energy Information Administration. October 2007. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- "U.S. Coal Consumption by End-Use Sector". Energy Information Administration. July 25, 2008. Retrieved August 29, 2008.

- Matthew Brown (March 17, 2013). "Company eyes coal on Montana's Crow reservation". The San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- Domestic and international coal distribution, US Energy Information Administration, 2013.

- US Domestic and Foreign Coal Distribution, US Energy Information, 2012.

- Government Accountability Office Coal Leasing: BLM Could Enhance Appraisal Process, More Explicitly Consider Coal Exports, and Provide More Public Information GAO-14-140. Published December 18, 2013. Released February 4, 2014

- CORAL DAVENPORT In Climate Move, Obama Halts New Coal Mining Leases on Public Lands The New York Times, January 14, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Henry, Devin (March 29, 2017). "Trump administration ends Obama's coal-leasing freeze". The Hill. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Matt Pearce Obama temporarily bans new coal leases on federal land Los Angeles Times, January 15, 2016.

- “Report- Almost $30 billion in revenues lost to taxpayers by “giveaway” of federally owned coal in Powder River Basin”, Institute for Energy Economic and Financial Analysis, June 25, 2012.

- “About”, Institute for Energy Economic and Financial Analysis. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- US Energy Information Administration, Table A5, Approximate heat content of coal and coal coke.

- US Energy Information Administration, Total coal mined.

- Primary energy production by source, US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved Apr. 2016.

- "Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries Summary, 2006 Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor". Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2006).

- "Panel to Explore Deadly Mine Accident". The New York Times. Associated Press. September 4, 2007.

- Urbina, Ian (April 9, 2010). "No Survivors Found After West Virginia Mine Disaster". The New York Times.

- Braun, Shannon (2010). "Coal, Identity, and the gendering of environmental justice activism in central appalacia". Gender and Society. 24 (6): 794–813. doi:10.1177/0891243210387277. JSTOR 25789907. S2CID 145551786.

- "Flood Advisory Task Force". 2002. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- Perdue, R., and G. Pavela. 2012. Addictive Economies and Coal Dependency: Methods of Extraction and Socioeconomic Outcomes in West Virginia 1997–2009. Organization and Environment. 25(4): 368–384.

- Fox, Julia (1999). "MOUNTAINTOP REMOVAL IN WEST VIRGINIA: An Environmental Sacrifice Zone". Organization & Environment. 12 (2): 168–183. doi:10.1177/1086026699122002. JSTOR 26161863. S2CID 110253546. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- "Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy 2007 Environment Survey" Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy website, March 7, 2007.

- "Iowans Want Energy Conservation Before New Coal Plants", Environment News Service, December 21, 2007.

- "Kansans Support Decision to Nix Coal Plants, Want Focus on Wind Energy", Lawrence Journal-World, January 4, 2008.

- Nace, Ted. "Stopping Coal In Its Tracks", Orion, January/February 2008.

- "Fight Against Coal Plants Draws Diverse Partners", The New York Times, October 20, 2007.

- "You're Getting Warmer" Archived February 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, East Bay Express, December 5, 2007.

- "Coal Scores With Wager on Bush Belief" Archived June 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post, March 25, 2001.

- "Spreading Misleading Messages", San Francisco Chronicle, November 3, 2004.

- "Coal Industry Plugs Into the Campaign", The Washington Post, January 18, 2008.

- "Greenwash of the Week: Coal Industry Buys Off CNN debates" Archived October 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Rainforest Action Network Understory blog, January 23, 2008.

- "U.S. Coal Reserves". EIA. November 4, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

Further reading

- Andrew B. Arnold, Fueling the Gilded Age: Railroads, Miners, and Disorder in the Pennsylvania Coal Country. New York: New York University Press, 2014.

- Walter Licht, Thomas Dublin (2005). The Face of Decline: The Pennsylvania Anthracite Region in the Twentieth Century. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8473-5. OCLC 60558740.

- Long, Priscilla (1991). Where the Sun Never Shines: A History of America's Bloody Coal Industry. New York: Paragon House. ISBN 978-1-55778-465-0. OCLC 25236866.

- Rottenberg, Dan (2003). In the Kingdom of Coal; An American Family and the Rock That Changed the World. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93522-7. OCLC 52348860.

- Thurber, Mark (2019). Coal. Polity Press. ISBN 978-1509514014.

- Smith, Duane A. (1993). Mining America: The Industry and the Environment, 1800–1980. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-87081-306-1.

- Freese, Barbara (2003). Coal: A Human History. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-7382-0400-0. OCLC 51449422.

.svg.png.webp)