Battle of Cold Harbor

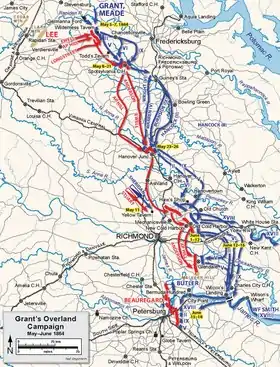

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign, and is remembered as one of American history's bloodiest, most lopsided battles. Thousands of Union soldiers were killed or wounded in a hopeless frontal assault against the fortified positions of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's army.

| Battle of Cold Harbor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

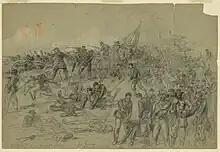

.jpg.webp) Union troops of the II Corps repelling a Confederate attack | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 108,000–117,000[11] | 59,000–62,000[11] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

12,738 total 1,845 killed 9,077 wounded 1,816 captured/missing[12][13] |

5,287 total 788 killed 3,376 wounded 1,123 captured/missing[13] | ||||||

On May 31, as Grant's army once again swung around the right flank of Lee's army, Union cavalry seized the crossroads of Old Cold Harbor, about 10 miles northeast of the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, holding it against Confederate attacks until the Union infantry arrived. Both Grant and Lee, whose armies had suffered enormous casualties in the Overland Campaign, received reinforcements. On the evening of June 1, the Union VI Corps and XVIII Corps arrived and assaulted the Confederate works to the west of the crossroads with some success.

On June 2, the remainder of both armies arrived and the Confederates built an elaborate series of fortifications 7 miles long. At dawn on June 3, three Union corps attacked the Confederate works on the southern end of the line and were easily repulsed with heavy casualties. Attempts to assault the northern end of the line and to resume the assaults on the southern were unsuccessful.

Grant said of the battle in his Personal Memoirs, "I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. ... No advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained." The armies confronted each other on these lines until the night of June 12, when Grant again advanced by his left flank, marching to the James River. In the final stage, Lee entrenched his army within besieged Petersburg before finally retreating westward across Virginia.

Background

Military situation

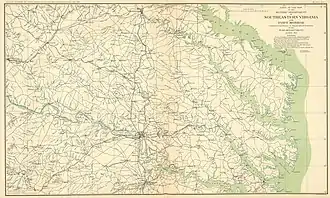

Grant's Overland Campaign was one of a series of simultaneous offensives the newly appointed general in chief launched against the Confederacy. By late May 1864, only two of these continued to advance: Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's Atlanta Campaign and the Overland Campaign, in which Grant accompanied and directly supervised the Army of the Potomac and its commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. Grant's campaign objective was not the Confederate capital of Richmond, but the destruction of Lee's army. President Abraham Lincoln had long advocated this strategy for his generals, recognizing that the city would certainly fall after the loss of its principal defensive army. Grant ordered Meade, "Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also."[14] Although he hoped for a quick, decisive battle, Grant was prepared to fight a war of attrition. Both Union and Confederate casualties could be high, but the Union had greater resources to replace lost soldiers and equipment.[15]

On May 5, after Grant's army crossed the Rapidan River and entered the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, it was attacked by Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Although Lee was outnumbered, about 60,000 to 100,000, his men fought fiercely and the dense foliage provided a terrain advantage. After two days of fighting and almost 29,000 casualties, the results were inconclusive and neither army was able to obtain an advantage. Lee had stopped Grant, but had not turned him back; Grant had not destroyed Lee's army. Under similar circumstances, previous Union commanders had chosen to withdraw behind the Rappahannock, but Grant instead ordered Meade to move around Lee's right flank and seize the important crossroads at Spotsylvania Court House to the southeast, hoping that by interposing his army between Lee and Richmond, he could lure the Confederates into another battle on a more favorable field.[16]

Elements of Lee's army beat the Union army to the critical crossroads of Spotsylvania Court House and began entrenching, a tactic that became increasingly essential for the outnumbered defenders.[17] Meade was dissatisfied with Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan's Union cavalry's performance and released it from its reconnaissance and screening duties for the main body of the army to pursue and defeat the Confederate cavalry under Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. Sheridan's men mortally wounded Stuart in the tactically inconclusive Battle of Yellow Tavern (May 11) and then continued their raid toward Richmond, leaving Grant and Meade without the "eyes and ears" of their cavalry.[18]

Near Spotsylvania Court House, fighting occurred on and off from May 8 through May 21, as Grant tried various schemes to break the Confederate line. On May 8, Union Maj. Gens. Gouverneur K. Warren and John Sedgwick unsuccessfully attempted to dislodge the Confederates under Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson from Laurel Hill, a position that was blocking them from Spotsylvania Court House. On May 10, Grant ordered attacks across the Confederate line of earthworks, which by now extended over 4 miles (6.5 km), including a prominent salient known as the Mule Shoe. Although the Union troops failed again at Laurel Hill, an innovative assault attempt by Col. Emory Upton against the Mule Shoe showed promise.[19]

Grant used Upton's assault technique on a much larger scale on May 12 when he ordered the 15,000 men of Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock's corps to assault the Mule Shoe. Hancock was initially successful, but the Confederate leadership rallied and repulsed his incursion. Attacks by Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright on the western edge of the Mule Shoe, which became known as the "Bloody Angle," involved almost 24 hours of desperate hand-to-hand fighting, some of the most intense of the Civil War. Supporting attacks by Warren and by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside were unsuccessful. In the end, the battle was tactically inconclusive, but with almost 32,000 casualties on both sides, it was the costliest battle of the campaign. Grant planned to end the stalemate by once again shifting around Lee's right flank to the southeast, toward Richmond.[20]

Grant's objective following Spotsylvania was the North Anna River, about 25 miles (40 km) south. He sent Hancock's Corps ahead of his army, hoping that Lee would attack it, luring him into the open. Lee did not take the bait and beat Grant to the North Anna. On May 23, Warren's V Corps crossed the river at Jericho Mills, fighting off an attack by A.P. Hill's corps, while Hancock's II Corps captured the bridge on the Telegraph Road. Lee then devised a plan, which represented a significant potential threat to Grant: a five-mile (8 km) line that formed an inverted "V" shape with its apex on the river at Ox Ford, the only defensible crossing in the area. By moving south of the river, Lee hoped that Grant would assume that he was retreating, leaving only a token force to prevent a crossing at Ox Ford. If Grant pursued, the pointed wedge of the inverted V would split his army and Lee could concentrate on interior lines to defeat one wing; the other Union wing would have to cross the North Anna twice to support the attacked wing.[21]

The Union Army assaulted the tip of the apex at Ox Ford and the right wing of the V. However, Lee, incapacitated in his tent by diarrhea, could not effect the attack he hoped to make. Grant realized the situation he was faced with and ordered his men to stop advancing and to build earthworks of their own. The Union general remained optimistic and was convinced that Lee had demonstrated the weakness of his army. He wrote to the Army's chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck: "Lee's army is really whipped. ... I may be mistaken but I feel that our success over Lee's army is already assured."[22]

As he did after the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, Grant planned another wide swing around Lee's flank, marching east of the Pamunkey River to screen his movements from the Confederates. His army disengaged on May 27 and crossed the river. Lee moved his army swiftly in response, heading for Atlee's Station on the Virginia Central Railroad, a point only 9 miles north of Richmond. There, his men would be well-positioned behind a stream known as Totopotomoy Creek to defend against Grant if he moved against the railroads or Richmond. Lee was not certain of Grant's specific plans, however; if Grant was not intending to cross the Pamunkey in force at Hanovertown, the Union army could outflank him and head directly to Richmond. Lee ordered cavalry under Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton to make a reconnaissance in force, break through the Union cavalry screen, and find the Union infantry.[23]

On May 28, Hampton's troopers encountered Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg in the Battle of Haw's Shop. Fighting predominately dismounted and utilizing earthworks for protection, neither side achieved an advantage. The battle was inconclusive, but it was one of the bloodiest cavalry engagements of the war. Hampton held up the Union cavalry for seven hours, prevented it from achieving its reconnaissance objectives, and had provided valuable intelligence to Lee about the disposition of Grant's army.[24]

After Grant's infantry had crossed to the south bank of the Pamunkey, Lee saw an opportunity on May 30 to attack Warren's advancing V Corps with his Second Corps, now commanded by Lt. Gen. Jubal Early. Early's divisions under Maj. Gens. Robert E. Rodes and Stephen Dodson Ramseur drove the Union troops back in the Battle of Bethesda Church, but Ramseur's advance was stopped by a fierce stand of infantry and artillery fire. On that same day, a small cavalry engagement at Matadequin Creek (the Battle of Old Church) drove an outnumbered Confederate cavalry brigade to the crossroads of Old Cold Harbor, verifying to Lee that Grant intended to move toward that vital intersection beyond Lee's right flank, attempting to avoid another stalemate on the Totopotomoy Creek line.[25]

Lee received notice that reinforcements were heading Grant's way from Bermuda Hundred. The 16,000 men of Maj. Gen. William F. "Baldy" Smith's XVIII Corps were withdrawn from Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler's Army of the James at Grant's request, and they were moving down the James River and up the York to the Pamunkey. If Smith moved due west from White House Landing to Old Cold Harbor, 3 miles (4.8 km) southeast of Bethesda Church and Grant's left flank, the extended Federal line would be too far south for the Confederate right to contain. Smith's men arrived at White House May 30–31. One brigade was left behind on guard duty, but about 10,000 men arrived to join Grant's army about 3 p.m. on June 1.[26]

Lee also received reinforcements. Confederate President Jefferson Davis directed Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard to send the division of Maj. Gen. Robert F. Hoke, over 7,000 men, from below the James River. (The first troops of Hoke's division arrived at Old Cold Harbor on May 31, but were unable to prevent the Union cavalry from seizing the intersection.) With these additional troops, and by managing to replace many of his 20,000 casualties to that point in the campaign, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia had 59,000 men to contend with Meade's and Grant's 108,000.[11] But the disparity in numbers was no longer what it had been—Grant's reinforcements were often raw recruits and heavy artillery troops, pulled from the defenses of Washington, D.C., who were relatively inexperienced in infantry tactics, while most of Lee's had been veterans moved from inactive fronts, and who were soon entrenched in impressive fortifications.[27]

Opposing forces

Union

Grant's Union forces totaled approximately 108,000 men.[11] They consisted of the Army of the Potomac, under Maj. Gen. George Meade, and the XVIII Corps, on temporary assignment from the Army of the James. The six corps were:[28]

- II Corps, under Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, including the divisions of Maj. Gen. David B. Birney and Brig. Gens. Francis C. Barlow, and John Gibbon.

- V Corps, under Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, including the divisions of Brig. Gens. Charles Griffin, Henry H. Lockwood, and Lysander Cutler. On June 6, the corps was reorganized to the divisions of Griffin, Cutler, and Brig. Gens. Romeyn B. Ayres and Samuel W. Crawford.

- VI Corps, under Brig. Gen. Horatio Wright, including the divisions of Brig. Gens. David A. Russell, Thomas H. Neill, and James B. Ricketts.

- IX Corps, under Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, including the divisions of Maj. Gen. Thomas Leonidas Crittenden and Brig. Gens. Robert B. Potter, Orlando B. Willcox, and Edward Ferrero. On June 9, Crittenden was replaced by Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie.

- Cavalry Corps, under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan, including the divisions of Brig. Gens. Alfred T.A. Torbert, David McM. Gregg, and James H. Wilson.

- XVIII Corps, under Maj. Gen. William F. "Baldy" Smith, including the divisions of Brig. Gens. William T. H. Brooks, John H. Martindale, and Charles Devens. On June 4, Devens became ill and was replaced by Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames.

Confederate

Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia comprised about 59,000 men[11] and was organized into four corps and two independent divisions:[29]

- First Corps, under Lt. Gen. Richard H. Anderson, including the divisions of Maj. Gens. Charles W. Field and George Pickett, and Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw.

- Second Corps, under Lt. Gen. Jubal Early, including the divisions of Maj. Gens. Stephen D. Ramseur, John B. Gordon, and Robert E. Rodes.

- Third Corps, under Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill, including the divisions of Maj. Gens. Henry Heth and Cadmus M. Wilcox, and Brig. Gen. William Mahone.

- Cavalry Corps, without a commander following the mortal wounding of Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart on May 11, including the divisions of Maj. Gens. Wade Hampton, Fitzhugh Lee, and W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee. (Hampton became the commander of the Cavalry Corps on August 11, 1864.)

- Breckinridge's Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge.

- Hoke's Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Robert F. Hoke.

Location

The battle was fought in central Virginia, in what is now Mechanicsville, over the same ground as the Battle of Gaines's Mill during the Seven Days Battles of 1862. Some accounts refer to the 1862 battle as the First Battle of Cold Harbor, and the 1864 battle as the Second Battle of Cold Harbor. Union soldiers were disturbed to discover skeletal remains from the first battle while entrenching. Cold Harbor was not a port city, despite its name. Rather, it described two rural crossroads named for the Cold Harbor Tavern (owned by the Isaac Burnett family) which provided shelter (harbor) but no hot meals. Old Cold Harbor stood two miles east of Gaines's Mill, and New Cold Harbor a mile southeast. Both were approximately 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Richmond, capital of the Confederacy. From these crossroads, the Union army was positioned to receive reinforcements sailing up the Pamunkey River, and could attack either the Confederate capital or its Army of Northern Virginia.[30]

Battle

May 31

The cavalry forces that had fought at Old Church continued to face each other on May 31. Lee sent a cavalry division under Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee to reinforce Brig. Gen. Matthew Butler and secure the crossroads at Old Cold Harbor. As Union Brig. Gen. Alfred T. A. Torbert increased pressure on the Confederates, Robert E. Lee ordered Anderson's First Corps to shift right from Totopotomoy Creek to support the cavalry. The lead brigade of Hoke's division also reached the crossroads to join Butler and Fitzhugh Lee. At 4 p.m. Torbert and elements of Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg's cavalry division drove the Confederates from the Old Cold Harbor crossroads and began to dig in. As more of Hoke's and Anderson's men streamed in, Union cavalry commander Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan became concerned and ordered Torbert to pull back toward Old Church.[31]

Grant continued his interest in Old Cold Harbor as an avenue for Smith's arrival and ordered Wright's VI Corps to move in that direction from his right flank on Totopotomoy Creek. He ordered Sheridan to return to the crossroads and secure it "at all hazards." Torbert returned at 1 a.m. and was relieved to find that the Confederates had failed to notice his previous withdrawal.[32]

June 1

Robert E. Lee's plan for June 1 was to use his newly concentrated infantry against the small cavalry forces at Old Cold Harbor. But his subordinates did not coordinate correctly. Anderson did not integrate Hoke's division with his attack plan and left him with the understanding that he was not to assault until the First Corps' attack was well underway, because the Union defenders were disorganized as well. Wright's VI Corps had not moved out until after midnight and was on a 15 miles (24 km) march. Smith's XVIII Corps had mistakenly been sent to New Castle Ferry on the Pamunkey River, several miles away, and did not reach Old Cold Harbor in time to assist Torbert.[33]

Anderson led his attack with the brigade formerly commanded by veteran Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw, which was now under a less experienced South Carolina politician, Col. Laurence M. Keitt. Keitt's men approached the entrenched cavalry of Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt. Armed with seven-shot Spencer repeating carbines, Merritt's men delivered heavy fire, mortally wounding Keitt and destroying his brigade's cohesion. Hoke obeyed what he understood to be his orders and did not join in the attack, which was quickly called back by Anderson.[34]

By 9 a.m. Wright's lead elements arrived at the crossroads and began to extend and improve the entrenchments started by the cavalrymen. Although Grant had intended for Wright to attack immediately, his men were exhausted from their long march and they were unsure as to the strength of the enemy. Wright decided to wait until after Smith arrived, which occurred in the afternoon, and the XVIII Corps men began to entrench on the right of the VI Corps. The Union cavalrymen retired to the east.[35]

For the upcoming attack, Meade was concerned that the corps of Wright and Smith would not be sufficient, so he attempted to convince Warren to send reinforcements. He wrote to the V Corps commander, "Generals Wright and Smith will attack this evening. It is very desirable you should join this attack, unless in your judgment it is impracticable." Warren decided to send the division of Brig. Gen. Henry H. Lockwood, which began to march at 6 p.m., but no adequate reconnaissance of the road network had been conducted and Lockwood was not able to reach the impending battle in time to make a difference. Meade was also concerned about his left flank, which was not anchored on the Chickahominy and was potentially threatened by Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry. He ordered Phil Sheridan to send scouting parties into the area, but Sheridan resisted, telling Meade that it would be impossible to move his men before dark.[36]

At 6:30 p.m. the attack that Grant had ordered for the morning finally began. Both Wright's and Smith's corps moved forward. Wright's men made little progress south of the Mechanicsville Road, which connected New and Old Cold Harbor, recoiling from heavy fire. North of the road, Brig. Gen. Emory Upton's brigade of Brig. Gen. David A. Russell's division also encountered heavy fire from Brig. Gen. Thomas L. Clingman's brigade, "A sheet of flame, sudden as lightning, red as blood, and so near that it seemed to singe the men's faces." Although Upton tried to rally his men forward, his brigade fell back to its starting point.[37]

To Upton's right, the brigade of Col. William S. Truex found a gap in the Confederate line, between the brigades of Clingman and Brig. Gen. William T. Wofford, through a swampy, brush-filled ravine. As Truex's men charged through the gap, Clingman swung two regiments around to face them, and Anderson sent in Brig. Gen. Eppa Hunton's brigade from his corps reserve. Truex became surrounded on three sides and was forced to withdraw, although his men brought back hundreds of Georgian prisoners with them.[38]

While action continued on the southern end of the battlefield, the three corps of Hancock, Burnside, and Warren were occupying a 5-mile line that stretched southeast to Bethesda Church, facing the Confederates under A.P. Hill, Breckinridge, and Early. At the border between the IX and V Corps, the division of Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden, recently transferred from the West following his poor performance in the Battle of Chickamauga, occupied a doglegged position with an angle that was parallel to the Shady Grove Road, separated from the V Corps by a marsh known as Magnolia Swamp. Two divisions of Early's Corps—Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes on the left, Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon on the right—used this area as their avenue of approach for an attack that began at 7 p.m. Warren later described this attack as a "feeler", and despite some initial successes, aided by the poor battle management of Crittenden, both Confederate probes were repulsed.[39]

At this same time, Warren's division under Lockwood had become lost wandering on unfamiliar farm roads. Despite having dispatched Lockwood explicitly, the V Corps commander wrote to Meade, "In some unaccountable way, [Lockwood] took his whole division, without my knowing it, away from the left of the line of battle, and turned up the dark 2 miles in my rear, and I have not yet got him back. All this time the firing should have guided him at least. He is too incompetent, and too high rank leaves us no subordinate place for him. I earnestly beg that he may at once be relieved of duty with this army." Meade relieved Lockwood and replaced him with Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford.[40]

By dark, the fighting had petered out on both ends of the line. The Union assault had cost it 2,200 casualties, versus about 1,800 for the Confederates, but some progress had been made. They almost broke the Confederate line, which was now pinned in place with Union entrenchments being dug only yards away. Several of the generals, including Upton and Meade, were furious at Grant for ordering an assault without proper reconnaissance.[41]

June 2

Although the June 1 attacks had been unsuccessful, Meade believed that an attack early on June 2 could succeed if he was able to mass sufficient forces against an appropriate location. He and Grant decided to attack Lee's right flank. Anderson's men had been heavily engaged there on June 1, and it seemed unlikely that they had found the time to build substantial defenses. And if the attack succeeded, Lee's right would be driven back into the Chickahominy River. Meade ordered Hancock's II Corps to shift southeast from Totopotomoy Creek and assume a position to the left of Wright's VI Corps. Once Hancock was in position, Meade would attack on his left from Old Cold Harbor with three Union corps in line, totaling 35,000 men: Hancock's II Corps, Wright's VI Corps, and Baldy Smith's XVIII Corps. Meade also ordered Warren and Burnside to attack Lee's left flank in the morning "at all hazards," convinced that Lee was moving troops from his left to fortify his right.[42]

Hancock's men marched almost all night and arrived too worn-out for an immediate attack that morning. Grant agreed to let the men rest and postponed the attack until 5 p.m., and then again until 4:30 a.m. on June 3. But Grant and Meade did not give specific orders for the attack, leaving it up to the corps commanders to decide where they would hit the Confederate lines and how they would coordinate with each other. No senior commander had reconnoitered the enemy position. Baldy Smith wrote that he was "aghast at the reception of such an order, which proved conclusively the utter absence of any military plan." He told his staff that the whole attack was, "simply an order to slaughter my best troops."[43]

Robert E. Lee took advantage of the Union delays to bolster his defenses. When Hancock departed Totopotomoy Creek, Lee was free to shift Breckenridge's division to his far right flank, where he would once again face Hancock. Breckinridge drove a small Union force off Turkey Hill, which dominated the southern part of the battlefield. Lee also moved troops from A.P. Hill's Third Corps, the divisions of Brig. Gens. William Mahone and Cadmus M. Wilcox, to support Breckinridge, and stationed cavalry under Fitzhugh Lee to guard the army's right flank. The result was a curving line on low ridges, 7 miles (11 km) long, with the left flank anchored on Totopotomoy Creek, the right on the Chickahominy River, making any flanking moves impossible.[44]

Lee's engineers used their time effectively and constructed the "most ingenious defensive configuration the war had yet witnessed." Barricades of earth and logs were erected. Artillery was posted with converging fields of fire on every avenue of approach, and stakes were driven into the ground to aid gunners' range estimates. A newspaper correspondent wrote that the works were, "Intricate, zig-zagged lines within lines, lines protecting flanks of lines, lines built to enfilade an opposing line, ... [It was] a maze and labyrinth of works within works." Heavy skirmish lines suppressed any ability of the Union to determine the strength or exact positions of the Confederate entrenchments.[45]

Although they did not know the details of their objectives, the Union soldiers who had survived the frontal assaults at Spotsylvania Court House seemed to be in no doubt as to what they would be up against in the morning. Grant's aide, Lt. Col. Horace Porter, wrote in his memoirs that he saw many men writing their names on papers that they pinned inside their uniforms, so their bodies could be identified. (The accuracy of this story is disputed as Porter is the only source.) One blood-spattered diary from a Union soldier found after the battle included a final entry: "June 3. Cold Harbor. I was killed."[46]

June 3

At 4:30 a.m. on June 3, the three Union corps began to advance through a thick ground fog. Massive fire from the Confederate lines quickly caused heavy casualties and the survivors were pinned down. Although the results varied in different parts of the line, the overall repulse of the Union advance resulted in the most lopsided casualties since the assault on Marye's Heights at the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862.[47]

The most effective performance of the day was on the Union left flank, where Hancock's corps was able to break through a portion of Breckinridge's front line and drive those defenders out of their entrenchments in hand-to-hand fighting. Several hundred prisoners and four guns were captured. However, nearby Confederate artillery was brought to bear on the entrenchments, turning them into a death trap for the Federals. Breckinridge's reserves counterattacked these men from the division of Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow and drove them off. Hancock's other advanced division, under Brig. Gen. John Gibbon, became disordered in swampy ground and could not advance through the heavy Confederate fire, with two brigade commanders (Cols. Peter A. Porter and H. Boyd McKeen) lost as casualties. One of Gibbon's men, complaining of a lack of reconnaissance, wrote, "We felt it was murder, not war, or at best a very serious mistake had been made."[48]

In the center, Wright's corps was pinned down by the heavy fire and made little effort to advance further, still recovering from their costly charge on June 1. The normally aggressive Emory Upton felt that further movement by his division was "impracticable." Confederate defenders in this part of the line were unaware that a serious assault had been made against their position.[49]

.jpg.webp)

On the Union right, Smith's men advanced through unfavorable terrain and were channeled into two ravines. When they emerged in front of the Confederate line, rifle and artillery fire mowed them down. A Union officer wrote, "The men bent down as they pushed forward, as if trying, as they were, to breast a tempest, and the files of men went down like rows of blocks or bricks pushed over by striking against one another." A Confederate described the carnage of double-canister artillery fire as "deadly, bloody work." The artillery fire against Smith's corps was heavier than might have been expected because Warren's V Corps to his right was reluctant to advance and the Confederate gunners in Warren's sector concentrated on Smith's men instead.[50]

The only activity on the northern end of the field was by Burnside's IX Corps, facing Jubal Early. He launched a powerful assault at 6 a.m. that overran the Confederate skirmishers but mistakenly thought he had pierced the first line of earthworks and halted his corps to regroup before moving on, which he planned for that afternoon.[51]

At 7 a.m. Grant advised Meade to vigorously exploit any successful part of the assault. Meade ordered his three corps commanders on the left to assault at once, without regard to the movements of their neighboring corps. But all had had enough. Hancock advised against the move. Smith, calling a repetition of the attack a "wanton waste of life," refused to advance again. Wright's men increased their rifle fire but stayed in place. By 12:30 p.m. Grant conceded that his army was done. He wrote to Meade, "The opinion of the corps commanders not being sanguine of success in case an assault is ordered, you may direct a suspension of further advance for the present." Union soldiers still pinned down before the Confederate lines began entrenching, using cups and bayonets to dig, sometimes including bodies of dead comrades as part of their improvised earthworks.[52]

Meade inexplicably bragged to his wife the next day that he was in command for the assault. But his performance had been poor. Despite orders from Grant that the corps commanders were to examine the ground, their reconnaissance was lax and Meade failed to supervise them adequately, either before or during the attack. He was able to motivate only about 20,000 of his men to attack—the II Corps and parts of the XVIII and IX—failing to achieve the mass he knew he required to succeed. His men paid heavily for the poorly coordinated assault. Estimates of casualties that morning are from 3,000 to 7,000 on the Union side, no more than 1,500 on the Confederate.[53] Grant commented after the war:

I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. I might say the same thing of the assault of the 22d of May, 1863, at Vicksburg. At Cold Harbor no advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained. Indeed, the advantages other than those of relative losses, were on the Confederate side. Before that, the Army of Northern Virginia seemed to have acquired a wholesome regard for the courage, endurance, and soldierly qualities generally of the Army of the Potomac. They no longer wanted to fight them "one Confederate to five Yanks." Indeed, they seemed to have given up any idea of gaining any advantage of their antagonist in the open field. They had come to much prefer breastworks in their front to the Army of the Potomac. This charge seemed to revive their hopes temporarily; but it was of short duration. The effect upon the Army of the Potomac was the reverse. When we reached the James River, however, all effects of the battle of Cold Harbor seemed to have disappeared.

— Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs[54]

At 11 a.m. on June 3, the Confederate postmaster general, John Henninger Reagan, arrived with a delegation from Richmond. He asked Robert E. Lee, "General, if the enemy breaks your line, what reserve have you?" Lee provided an animated response: "Not a regiment, and that has been my condition ever since the fighting commenced on the Rappahannock. If I shorten my lines to provide a reserve, he will turn me; if I weaken my lines to provide a reserve, he will break them.".[55] Modern scholarship has shown Lee had ample reserves unengaged. His comments likely were to persuade Richmond to send more troops.[56]

June 4–12

Grant and Meade launched no more attacks on the Confederate defenses at Cold Harbor. The two opposing armies faced each other for nine days of trench warfare, in some places only yards apart. Sharpshooters worked continuously, killing many. Union artillery bombarded the Confederates with a battery of eight Coehorn mortars; the Confederates responded by depressing the trail of a 24-pound howitzer and lobbing shells over the Union positions. Although there were no more large-scale attacks, casualty figures for the entire battle were twice as large as from the June 3 assault alone.[57]

The trenches were hot, dusty, and miserable, but conditions were worse between the lines, where thousands of wounded Federal soldiers suffered horribly without food, water, or medical assistance. Grant was reluctant to ask for a formal truce that would allow him to recover his wounded because that would be an acknowledgment he had lost the battle. He and Lee traded notes across the lines from June 5 to 7 without coming to an agreement, and when Grant formally requested a two-hour cessation of hostilities, it was too late for most of the unfortunate wounded, who were now bloated corpses. Grant was widely criticized in the Northern press for this lapse of judgment.[58]

Every corpse I saw was as black as coal. It was not possible to remove them. They were buried where they fell. ... I saw no live man lying on this ground. The wounded must have suffered horribly before death relieved them, lying there exposed to the blazing southern sun o' days, and being eaten alive by beetles o' nights.

Union artillery officer, Frank Wilkeson[59]

On June 4 Grant tightened his lines by moving Burnside's corps behind Matadequin Creek as a reserve and moving Warren leftward to connect with Smith, shortening his lines about 3 miles (4.8 km). On June 6 Early probed Burnside's new position but could not advance through the impassable swamps.[60] Grant realized that, once again in the campaign, he was in a stalemate with Lee and additional assaults were not the answer. He planned three actions to make some headway. First, in the Shenandoah Valley, Maj. Gen. David Hunter was making progress against Confederate forces, and Grant hoped that by interdicting Lee's supplies, the Confederate general would be forced to dispatch reinforcements to the Valley. Second, on June 7 Grant dispatched his cavalry under Sheridan (the divisions of Brig. Gens. David McM. Gregg and Wesley Merritt) to destroy the Virginia Central Railroad near Charlottesville. Third, he planned a stealthy operation to withdraw from Lee's front and move across the James River. Lee reacted to the first two actions as Grant had hoped. He pulled Breckinridge's division from Cold Harbor and sent it toward Lynchburg to parry Hunter. By June 12 he followed this by assigning Jubal Early permanent command of the Second Corps and sending them to the Valley as well. And he sent two of his three cavalry divisions in pursuit of Sheridan, leading to the Battle of Trevilian Station. However, despite anticipating that Grant might shift across the James, Lee was taken by surprise when it occurred. On June 12 the Army of the Potomac finally disengaged to march southeast to cross the James and threaten Petersburg, a crucial rail junction south of Richmond.[61]

Aftermath

The Battle of Cold Harbor was the final victory won by Lee's army during the war (part of his forces won the Battle of the Crater the following month, during the Siege of Petersburg, but this did not represent a general engagement between the armies), and its most decisive in terms of casualties. The Union army, in attempting the futile assault, lost 10,000 to 13,000 men over twelve days. The battle brought the toll in Union casualties since the beginning of May to a total of more than 52,000, compared to 33,000 for Lee. Although the cost was great, Grant's larger army finished the campaign with lower relative casualties than Lee's.[62]

Estimates vary as to the casualties at Cold Harbor. The following table summarizes estimates from a variety of popular sources:[63]

| Source | Union | Confederate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Killed | Wounded | Captured/ Missing |

Total | Killed | Wounded | Captured/ Missing |

Total | |

| National Park Service | 13,000 | 2,500 | ||||||

| Kennedy, Civil War Battlefield Guide | 13,000 | 5,000 | ||||||

| King, Overland Campaign Staff Ride | 12,738 | 3,400 | ||||||

| Bonekemper, Victor, Not a Butcher | 1,844 | 9,077 | 1,816 | 12,737 | 83 | 3,380 | 1,132 | 4,595 |

| Eicher, Longest Night | 12,000 | "few thousand" | ||||||

| Rhea, Cold Harbor | 3,500–4,000 (June 3 only) |

1,500 | ||||||

| Trudeau, Bloody Roads South | 12,475 | 2,456 | 14,931 | 3,765 | 1,082 | 4,847 | ||

| Young, Lee's Army | 788 | 3,376 | 1,123 | 5,287 | ||||

Some authors (Catton, Esposito, Foote, McPherson, Grimsley) estimate the casualties for the major assault on June 3 and all agree on approximately 7,000 total Union casualties, 1,500 Confederate. Gordon Rhea, considered the preeminent modern historian of Grant's Overland Campaign, has examined casualty lists in detail and has published a contrarian view in his 2002 book, Cold Harbor. For the morning assault on June 3, he can account for only 3,500 to 4,000 Union killed, wounded, and missing, and estimates that for the entire day the Union suffered about 6,000 casualties, compared to Lee's 1,000 to 1,500. Rhea noted that although this was a horrific loss, Grant's main attack on June 3 was dwarfed by Lee's daily losses at Antietam, Chancellorsville, and Pickett's Charge, and is comparable to Malvern Hill.[64]

The battle caused a rise in anti-war sentiment in the Northern states. Grant became known as the "fumbling butcher" for his poor decisions. It also lowered the morale of his remaining troops. But the campaign had served Grant's purpose—as ill-advised as his attack on Cold Harbor was, Lee had lost the initiative and was forced to devote his attention to the defense of Richmond and Petersburg. He beat Grant to Petersburg, barely, but spent the remainder of the war (save its final week) defending Richmond behind a fortified trench line. Although Southerners realized their situation was desperate, they hoped that Lee's stubborn (and bloody) resistance would have political repercussions by causing Abraham Lincoln to lose the 1864 presidential election to a more peace-friendly candidate. The taking of Atlanta in September dashed these hopes, and the end of the Confederacy was just a matter of time.[65]

Cold Harbor Tavern and Garthright House

During the battle, Burnett's tavern (no longer standing) was used as a hospital. Union soldiers carried away all items of value, except for a crystal compote bowl saved by Mrs. Burnett. The Garthright House was also used as a field hospital, the exterior of which is now preserved.[66]

Battlefield preservation

In 2008, the Civil War Trust (a division of the American Battlefield Trust) placed the Cold Harbor battlefield on its Ten Most Endangered Battlefields list. Development pressure in the Richmond area was so great that only about 300 acres (1.2 km2) of what was once at least a 7,500-acre (30 km2) battlefield are currently preserved as part of the Richmond National Battlefield Park. Hanover County also maintains a small 50 acre park adjacent to the NPS's Cold Harbor holdings.[67] The Trust and its partners have acquired and preserved 250 acres (1.0 km2) of the battlefield through late 2021.[68]

See also

Notes

- Battle of Cold Harbor Facts & Summary American Battlefield Trust

- Furgurson 2000, p. 525.

- Rhea 2002, p. 357.

- Cold Harbor National Park Service

- Bruce Catton, Never Call Retreat (Doubleday, New York, 1965) pp. 363–364

- Shelby Foote The Civil War: Yellow Tavern to Cold Harbor (Time Life Edition, 2000) pp. 87–110

- "Robert e. Lee's Last Great Victory: Clash at Cold Harbor". December 14, 2016.

- "Battle of Cold Harbor | Summary".

- Further information:

Organization of Army of the Potomac, May 31, 1864: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXXVI, Part 1, pp. 198–209. - Temporarily attached to the Army of the Potomac from the Army of the James. See: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXXVI, Part 1, page 178 (note at the bottom of the page).

- Eicher, p. 685; Esposito, text for map 136. Salmon, p. 295, cites Confederate strength of 62,000. Kennedy, p. 294, cites 117,000 Union, 60,000 Confederate. McPherson, p. 733, cites 109,000 Union, 59,000 Confederate.

- Return of Casualties in the Union forces, Battle of Cold Harbor, June 2–15, 1864 (Recapitulation): Official Records, Series I, Volume XXXVI, Part 1, p. 180.

- Union casualties are from Bonekemper, p. 311, Confederate from Young, p. 240. Estimates from other authors are summarized in the Aftermath section.

- Hattaway & Jones, p. 525; Trudeau, pp. 29–30.

- Eicher, pp. 661–662; Kennedy, p. 282; Jaynes, pp. 25–26; Rhea, p. 369; Grimsley, pp. 94–110, 118–129, provides details on the failed campaigns (the Bermuda Hundred Campaign and Franz Sigel's campaign in the Shenandoah Valley) that were part of Grant's "peripheral strategy."

- Salmon, p. 253; Kennedy, pp. 280–282; Eicher, pp. 663–671; Jaynes, pp. 56–81.

- Earl J. Hess, Trench Warfare Under Grant and Lee: Field Fortifications in the Overland Campaign (2007)

- Jaynes, pp. 82–86, 114–124; Eicher, pp. 673–674; Salmon, pp. 270–271, 279–283; Kennedy, pp. 283, 286.

- Salmon, pp. 271–275; Kennedy, p. 285; Eicher, pp. 671–673, 675–676.

- Salmon, pp. 275–279; Kennedy, pp. 285–286; Eicher, pp. 676–679; Jaynes, pp. 124–130.

- Welcher, 980; Grimsley, p. 141; Salmon, p. 285; Kennedy, p. 289; Trudeau, pp. 236, 241.

- Jaynes, p. 137; Trudeau, p. 239; Grimsley, pp. 145–148; Esposito, text for map 135.

- Rhea, pp. 32–37, 41–44, 50–57; Eicher, pp. 671, 679, 683; Salmon, p. 288; Furgurson, pp. 43–47; Grimsley, pp. 149–151.

- Jaynes, p. 149; Furgurson, pp. 49–52; Salmon, p. 288; Grimsley, pp. 151–152; Rhea, pp. 68–71, 87–88.

- Grimsley, pp. 156–159; Kennedy, pp. 290–291; Salmon, pp. 290–294.

- King, pp. 295–296; Welcher, pp. 986–987; Kennedy, p. 291.

- Furgurson, pp. 58–60; Rhea, pp. 13, 162; Kennedy, p. 291.

- Welcher, pp. 994–997.

- Rhea, pp. 410–417.

- For an example reference to the First Battle of Cold Harbor, see "battles of Cold Harbor", Encyclopædia Britannica online, accessed May 30, 2012; McPherson, p. 733; Foote, p. 281; Kennedy, p. 291; Eicher, p. 685.

- Grimsley, pp. 196–199; Furgurson, pp. 81–82; Kennedy, pp. 291–293.

- Trudeau, pp. 262–263; King, p. 296; Kennedy, p. 293; Grimsley, pp. 199–201.

- Kennedy, pp. 291–293; Grimsley, pp. 202–203; Trudeau, p. 265.

- Jaynes, p. 152; Welcher, p. 986; Trudeau, pp. 266–267; Grimsley, p. 201; Furgurson, pp. 89–94.

- Furgurson, pp. 94–95; Welcher, pp. 986–987.

- Rhea, pp. 229–230.

- Rhea, p. 241; Furgurson, p. 99; Grimsley, pp. 203–206; Welcher, p. 988; Trudeau, p. 269, states that Smith's assault began at 5 p.m.

- Grimsley, pp. 204–206; Welcher, p. 988.

- Rhea, pp. 256–59; Grimsley, pp. 208–209.

- Rhea, pp. 259–260; Furgurson, pp. 112–113.

- Jaynes, p. 154; Rhea, pp. 266–268; Trudeau, p. 273, states that the fighting stopped by 10 p.m.

- Kennedy, p. 293; Grimsley, pp. 207–208; Welcher, p. 989.

- Jaynes, p. 156; Furgurson, pp. 120–121; Grimsley, p. 207; Trudeau, pp. 276–277; King, p. 297; Welcher, p. 989.

- Welcher, p. 989; Salmon, p. 295; Grimsley, p. 208.

- McPherson, p. 735; Jaynes, p. 156; Grimsley, pp. 209–210.

- Foote, p. 290; Salmon, p. 296; Grimsley, p. 210; Trudeau, pp. 280, 297.

- Salmon, p. 296; Trudeau, p. 284; Catton, p. 267.

- Rhea, pp. 360–361; Grimsley, pp. 211–212; Trudeau, pp. 285–286, 289–290; King, p. 304.

- Grimsley, pp. 214–215; Trudeau, pp. 286, 290; King, p. 305.

- Rhea, pp. 353, 356; Grimsley, p. 215; Trudeau, pp. 286, 290–291.

- Welcher, p. 992; Grimsley, pp. 215–216.

- Rhea, pp. 374–379; Grimsley, pp. 216–217.

- Rhea, p. 234; Catton, p. 265. See additional casualty estimates in the Aftermath section.

- Grant, vol. 2, pp. 276–277.

- Grimsley, p. 220; Foote, p. 293.

- Rhea, p. 273.

- Catton, p. 267; Furgurson, pp. 181–182; Trudeau, p. 298.

- King, p. 311: "Under the accepted rules of warfare of the 19th century, the losing side in a battle was supposed to send a flag of truce to the victor to ask for a cease-fire that would allow both sides to recover their dead and wounded." Grimsley, p. 220; Trudeau, pp. 304–306.

- Grimsley, p. 221.

- Furgurson, pp. 206–208.

- McPherson, p. 737; Trudeau, pp. 305–306; Eicher, pp. 686–687; Salmon, pp. 258–259; Grimsley, p. 223; Esposito, text for map 136.

- Salmon, pp. 259, 296, cites 55,000 total Union campaign casualties, 27,000 Confederate. Esposito, text to map 137, cites 55,000 Union, 20–40,000 Confederate. Trudeau, p. 341, cites 54,000 Union, 32,000 Confederate.

- National Park Service Archived June 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (also Salmon, p. 296); Bonekemper, p. 311; Eicher, p. 686; Kennedy, p. 294; King, p. 307; Rhea, p. 386; Trudeau, p. 341; Young, p. 240.

- Rhea, p. 386. Claims for Union June 3 casualties in the 7,000 range can be found in Grimsley, p. 219, McPherson, p. 735, Catton, p. 267, and Esposito, text for map 136. Shelby Foote, p. 292, claims that the 7,000 casualties were suffered in the first 8 minutes of the battle.

- Kennedy, p. 294; Salmon, p. 259.

- Richmond Then and Now website. Archived May 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Civil War Trust's Most Endangered Battlefields 2008.

- American Battlefield Trust "Saved Land" webpage. Accessed November 23, 2021.

Bibliography

- Bonekemper III, Edward H. (2010). Ulysses S. Grant: A Victor, Not a Butcher: The Military Genius of the Man Who Won the Civil War Ulysses S. Grant: A Victor, Not a Butcher. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5969-8641-1.

- —— (2015) [1968]. Grant Takes Command. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-13210-7.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 3, Red River to Appomattox. New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 0-394-74913-8.

- Fuller, J.F.C. Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982.

- Furgurson, Ernest B. (2000). Not War But Murder: Cold Harbor, 1864. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-45517-2.

- Grimsley, Mark. And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May–June 1864. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8032-2162-2.

- Hess, Earl J. (2007). Trench Warfare Under Grant and Lee: Field Fortifications in the Overland Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3154-0.

- Hogan, David W. Jr. The Overland Campaign Archived April 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History, 2014. ISBN 978-0160925177.

- Jaynes, Gregory, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Killing Ground: Wilderness to Cold Harbor. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1986. ISBN 0-8094-4768-1.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- King, Curtis S., William G. Robertson, and Steven E. Clay. Staff Ride Handbook for the Overland Campaign, Virginia, 4 May to 15 June 1864: A Study on Operational-Level Command Archived May 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. (PDF document Archived November 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine). Fort Leavenworth, Kan.: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2006. OCLC 62535944.

- McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1950-3863-7.

- Rhea, Gordon C. (2002). Cold Harbor: Grant and Lee, May 26–June 3, 1864. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2803-9.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. Bloody Roads South: The Wilderness to Cold Harbor, May–June 1864. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1989. ISBN 978-0-316-85326-2.

- Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 1, The Eastern Theater. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-253-36453-1.

- Young, Alfred C., III (2013). Lee's Army during the Overland Campaign: A Numerical Study. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-5172-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - National Park Service battle description

- CWSAC Report Update

Memoirs and primary sources

- Atkinson, Charles Francis. Grant's Campaigns of 1864 and 1865: The Wilderness and Cold Harbor (May 3 – June 3, 1864). The Pall Mall military series. London: H. Rees, 1908. OCLC 2698769.

- Badeau, Adam. Military History of Ulysses S. Grant (Vol. III). New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1881.

- Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. 2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. ISBN 0-914427-67-9.

- Longstreet, James. From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America. New York: Da Capo Press, 1992. ISBN 0-306-80464-6. First published in 1896 by J. B. Lippincott and Co.

- Porter, Horace. Campaigning with Grant. New York: Century Co., 1897. OCLC 913186.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

Further reading

- Davis, Daniel T., and Phillip S. Greenwalt. Hurricane from the Heavens: The Battle of Cold Harbor, May 26–June 5, 1864. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2014. ISBN 978-1-61121-187-0.

External links

- Battle of Cold Harbor: Battle Maps, histories, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- Animated map of the Overland Campaign (Civil War Trust)

- National Park Service battlefield site

- 48th New York Infantry account of battle

- Union Army Battle Report

- NYTimes remembrance of 150th anniversary of the battle