Cold Spring, New York

Cold Spring is a village in the town of Philipstown in Putnam County, New York, United States. The population was 1,986 at the 2020 census.[2] It borders the smaller village of Nelsonville and the hamlets of Garrison and North Highlands. The central area of the village is on the National Register of Historic Places as the Cold Spring Historic District due to its many well-preserved 19th-century buildings, constructed to accommodate workers at the nearby West Point Foundry (itself a Registered Historic Place today). The town is the birthplace of General Gouverneur K. Warren, who was an important figure in the Union Army during the Civil War. The village, located in the Hudson Highlands, sits at the deepest point of the Hudson River, directly across from West Point. Cold Spring serves as a weekend getaway for many residents of New York City.

Cold Spring, New York | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Main Street, Cold Spring, part of the federally recognized historic district. | |

Seal | |

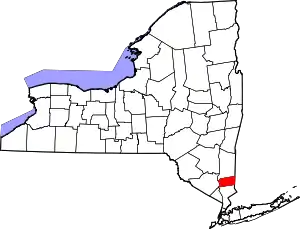

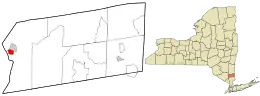

Location in Putnam County and the state of New York. | |

| Coordinates: 41°25′8″N 73°57′16″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Putnam |

| Incorporated | 1846 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Kathleen E. Foley |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.60 sq mi (1.55 km2) |

| • Land | 0.59 sq mi (1.54 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.01 km2) 0.91% |

| Elevation | 108 ft (33 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 1,986 |

| • Density | 3,343.43/sq mi (1,291.51/km2) |

| Area code | 845 |

| FIPS code | 36-16936 |

| Website | coldspringny |

Commuter service to New York City is available via the Cold Spring train station, served by Metro-North Railroad. The train journey is approximately one hour, ten minutes to Grand Central Terminal.

History

Background

Prior to contact with Europeans, native perspectives regarding land ownership and usage rights were based on an oral tradition of religious and spiritual teachings. These teachings described the land as a living relative who helped in providing for native peoples' existence. As the concept of landownership was therefore at odds with these religious teachings, land was often used communally by those within their community. This perspective differed greatly from increasingly rigid concepts of land ownership and property rights which existed in Europe, Asia (originally the Middle East) for millennia.

These conflicting perspectives regarding concepts of ownership and usage rights resulted in mutual frustration and violence between natives and settlers. While natives quickly understood and adapted to European models of property rights and land ownership, the colonial government in New Amsterdam (seeking to improve trade with natives by limiting violent conflict) created a procedure for land transactions involving natives holding original Indian title of the land to be sold to settlers.

According to this procedure, settlers seeking land ownership in colonial New Amsterdam were required to apply to the colonial government for a license that would allow them to negotiate with and purchase a deed to land held by Native Americans. Only after securing a deed to the land with the consent of local natives would the settlers be granted a land patent to the property.

Early History

On December 2, 1680, Dutch traders Lambert Dorlandt and Jan Roelof Sybrandt (Seberinge) applied to purchase a license from Colonial Governor Benjamin Fletcher for a roughly 15,000 acre tract along the eastern shore of the Hudson River shore in present-day Putnam County. At the time, the region sparsely inhabited by Wappinger villages. According to local historians, Dortlandt and Sybrant "obtained a license... in October [of] 1687 permitting their purchase of a deed from the Native Americans." According to historians Oscar Handlin and Irving Mark, the deed "described as a strip of land along the Hudson shore in the Highland, 'beginning at the north side of a hill called Anthony’s Nose at a marked Red Seader Tree, and along said River Northerly to the Land belonging to Stephanus Van Cortlandt and the Heirs of Francis Rhombout and G. Verplanck, and Eastwards in the Woods as far along the said Lands of Stephanus [Van] Cortland and Co. aforesaid to a marked tree...”

On July 15, 1691, Dortlandt and Sybrant secured a deed to the tract from Wappinger leaders, totaling as much as much as 17,480 acres (according to recent historical analysis)[3] along the eastern bank of the Hudson River from the peak on Anthony's Nose to (and including) Pollepel Island, and east to a marked tree which would establish the tract's eastern border.[3] This tract contained a large portion of modern-day Phillipstown, NY, including the entire the Village of Cold Spring.

While many land transactions in colonial America were disputed by settlers and natives, the original lands deeded to Dortlandt and Sybrant (containing the Village of Cold Spring) appear to have been legitimately obtained with the consent of the Wappinger. This is evidenced by testimony from Wappinger leader Daniel Nimham, who, in 1765, sought the assistance of the New York Common Council (and eventually the British Crown) in resolving land disputes over land claimed both by the heirs of Adolph Philipse and Wappinger natives. In this testimony, Nimham states that Wappinger ancestors had sold a tract of "Low Lands on that Part of the Peeks kill [north of modern-day Annsville Creek]... and also a pine swamp containing... a few Acres called Kichtondacongh and a piece of low Land lying Southeasterly from Kichtondacongh called Paukeminshingh."[3] Nimham goes on to contest the sale of any land beyond this initial tract deeded by the Wappinger to Dortlandt and Sybrant, however, recognizes the initial transaction of land (including present-day Cold Spring)as legitimately ceded by the Wappinger to the Dutch.[4]

Permanent Settlements

The first permanent settler in the village of Cold Spring was Merrick Williams in 1730. In 1772, a highway master was chosen for the road from Cold Spring to the Post Road from New York to Albany. Prior to Williams presence, the land was woodlands. A small trading hamlet grew alongside the river by the early 1800s.[5] A couple of sloops made regular weekly trips from Cold Spring to New York, carrying wood and some country produce, which came over this model road from the east. Those trips by sloop usually took a week.

In 1818, Gouverneur Kemble established the West Point Foundry opposite West Point to produce artillery pieces for the United States Government. The nearby mountains contained veins of ore, and were covered with timber for fuel. A brook provided hydropower, and the Hudson a ready shipping outlet. In 1843, the Foundry built the USS Spencer, the first iron ship built in the U.S.[6] With the influx of workers at the Foundry, local housing, businesses and churches increased, and Cold Spring was incorporated as a village in 1846. The first President of the Village was Joshua Haight. The Foundry became famous for its production of Parrott rifles and other munitions during the Civil War, when the foundry grew to a sprawling 100-acre complex employing 1,400. It also manufactured cast iron steam engines for locomotives, gears, and produced much of the pipework for New York's water system. The rise of steel making and the declining demand for cast iron after the Civil War caused the Foundry to cease operations in 1911.[7]

Many artifacts from the Foundry's history can be viewed at the Putnam History Museum on Chestnut Street. Built in 1830, the building was originally a one-room schoolhouse for the Foundry's teenage apprentices and the children of employees.[8]

On January 22, 1896, local businessmen of Cold Spring formed a fire brigade known as the Cold Spring Hose Company, No.1. A horse-drawn hook and ladder was donated in 1899.[9] The Municipal Building, designed by Louis Mekeel, was constructed in 1926 to house the company's first firetruck, an American LaFrance. The company, renamed Cold Spring Fire Company No.1 in 1900, serves the Villages of Cold Spring, Nelsonville and a district in the Town of Philipstown.[10]

Mr. Willis Buckner, a former slave from the South, was a driver and groom for Susan and Anna Bartlett Warner at their farm on Constitution Island. Mr. Buckner taught Sunday School at the Methodist Church.[9] In the early decades of the 20th century, blacks who stayed in this part of New York state migrated away from rural towns to nearby cities with waterfront manufacturing such as Peekskill, Beacon, Newburgh and Ossining. During the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan had a presence in Cold Spring[11] as well as Fishkill and Nelsonville.

.jpg.webp)

Pete Seeger formed the Clearwater organization, an environmental group dedicated to advances in sewer treatment, industrial waste disposal, and addressing the discharge of major pollutants into the Hudson. In 1970, the sloop Clearwater docked for a songfest at Cold Spring. As Seeger appeared on stage to thank the audience for coming, fifteen drunks stood up waving little American flags, yelling “Throw the Commies out.” That night someone cut the sloop's moorings and there were threats to torch the boat. All of this created tension within the Clearwater organization. [12]

Country estates

Towards the latter part of the nineteenth century artists, writers and prominent families were drawn to Cold Spring by the beauty of the Hudson Highlands. Mansions were built along Morris Avenue, including "Undercliff," the home of publisher George Pope Morris, and "Craigside," the home of Julia and General Daniel Butterfield.[5] To the south, West Point Foundry employees Dr. Frederick Lente built "The Grove," Robert Parker Parrott built "Plumbush," and Hudson River School painter Thomas P. Rossiter built "Fair Lawn."

Undercliff

Undercliff Fair Lawn

Fair Lawn Plumbush

Plumbush

Attractions

Cold Spring’s main street attracts tourists in all seasons. Retail, restaurants, and nearby walks and hikes draw visitors from the region with ferry service providing transportation for tourists in autumn. The Foundry Preserve Trail is an easy in-town walk, while the trailheads to the north offer more rigorous options including Breakneck Ridge.

The Julia L. Butterfield Memorial Library was established in 1913, through the Will of Mrs. Julia L. Butterfield. The Library building was built on the foundation of the Dutch Reformed Church in 1922. The Library opened in May 1925.[13]

In 2017, art collectors Nancy Olnick and Giorgio Spanu opened Magazzino Italian Art, a 20,000 sq. ft museum focusing on Postwar and Contemporary Italian Art.[14][15] Admission to the museum is free to the public.[16]

Six miles east of the village is Clarence Fahnestock State Park and the Appalachian Trail. The park offers camp sites, hikes, picnic grounds, and lakes. Within Fahnestock is Stonecrop Gardens, a traditional Alpine garden open to the public since 1992. Stonecrop was created by Garden Conservancy founder Frank Cabot and his wife, Anne, in 1958.[17] Adjacent to Stonecrop is Glynwood Center for Regional Food and Farming.

Geography

The village is bordered by the Hudson River to the west, and is bound by the Hudson Highlands State Park to the north, where Mount Taurus and Breakneck Ridge rise steeply and dramatically out of the banks of the Hudson and form two basically parallel ridges that track each other inland. The valley between them has an abandoned dairy farm, two lakes, and a camp. The view from the river bank is the Constitution Marsh and the US Military Academy (West Point) slightly to the south, and Crow's Nest and Storm King Mountain to the west and northwest. All of this considered, the village is nestled in the most prominent vertical terrain on the Hudson River north of New York City prior to the Shawangunk and Catskill ranges. Being bound by these formidable terrain features has kept the size of the village small, and prevented the suburban sprawl that has come about in the less-constrained regions to the north and south and in the New York Metropolitan area generally. This unique sense of place, and the village's historic housing stock, have made it a very popular weekend destination for tourists from New York City. Its oldest current home is located on 191 Main Street and was built in 1814. Some say Abraham Lincoln visited that house when he visited Cold Spring.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 0.60 square miles (1.55 km2), of which 0.59 square miles (1.54 km2) is land and 0.004 square miles (0.01 km2), or 0.91%, is water.[18]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 2,770 | — | |

| 1870 | 3,086 | 11.4% | |

| 1880 | 2,111 | −31.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,067 | — | |

| 1910 | 2,549 | 23.3% | |

| 1920 | 1,433 | −43.8% | |

| 1930 | 1,784 | 24.5% | |

| 1940 | 1,897 | 6.3% | |

| 1950 | 1,788 | −5.7% | |

| 1960 | 2,083 | 16.5% | |

| 1970 | 2,083 | 0.0% | |

| 1980 | 2,161 | 3.7% | |

| 1990 | 1,998 | −7.5% | |

| 2000 | 1,983 | −0.8% | |

| 2010 | 2,013 | 1.5% | |

| 2020 | 1,986 | −1.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[19] | |||

As of the census[20] of 2020, there were 1,986 people, 834 households, and 834 families residing in the village. The population density was 3,300 inhabitants per square mile (1,300/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 94% White, 0.49% African American, 0.44% Native American, 3.05% Asian, 2.12% from other races, and 0.08% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.07% of the population.

Out of the 834 households, 25.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.9% were married couples living together. The average household size was 2.13 and the average family size was 3.0.

The median income for a household in the village was $98,056 (an increase of 83.7% from 2010), and the median income for a family was $135,500 (an increase of 78.2% from 2010). About 8.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.8% of those under age 18 and 4.4% of those age 65 or over.

Churches

Under the auspices of Superintendent William Young, a Presbyterian from the north of Ireland, arrangements were to conduct religious services in the pattern shop. The premises was shared by Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and Baptists. The Methodists used a private home. Once every three weeks Rev. Owens from Patterson came to minister to the Presbyterians. Elder Warren from Kent cared for the religious needs of the Baptists. In the absence of an ordained minister, services were occasionally conducted by Foundry President Gouverneur Kemble. 1826 the Union Church was built. The celebrated preacher Thomas De Witt Talmage from Brooklyn is reported to have sometimes officiated there. The sacramental vessels were of pewter. By mutual agreement the Presbyterians used the building in the morning and the other religious groups in the afternoon. In 1830 the Baptists constructed a church on land donated by Samuel L. Gouverneur.

The first Methodist church was built in 1833[21] on the corner of Main and Church Streets. The building was sold in 1870. A new brick Italianate structure, designed by William Humphreys Jr., was built in 1868 on the north side of Main Street.[9]

The Dutch Reformed Church was built around 1855 in Neoclassical style. The building was later replaced by the Julia L. Butterfield Library.

Our Lady of Loretto

Many of the workers at the Foundry were Irish immigrants. As early as 1830, Rev. Fr Philip O'Reilly O.P., from County Cavan, Ireland visited Cold Spring to minister to Catholics. At that time, O'Reilly was also attending to congregations in Newburgh and High Falls. O'Reilly raised money to build a church, and Foundry owner Gouverneur Kemble, an Episcopalian, donated the land and funds. Kemble was denounced in the local newspaper for "abetting the idolatry of the mass".[22] The building was designed in the Greek Revival style by Thomas Kelah Wharton. It was constructed in 1833 of locally made red brick covered with stucco. The church stood twenty-five feet above the river and fifteen feet from the edge of promontory on which it was set. The church was consecrated on Sunday, September 21, 1834 by Bishop John DuBois.[23] In 1837 Rev. Patrick Duffy became pastor, with mission outposts in Newburgh, Poughkeepsie, and Saugerties.[22]

Workers tested cannons by firing at Storm King Mountain. Test firing from the Foundry damaged the chapel walls, and Captain Robert P. Parrott, the then Foundry superintendent paid for repairs. Victorian additions altered the building's integrity, and the coming of the railroad cut it off from the rest of the village. The church was abandoned in 1906 and fell into disrepair. A fire caused further damage in 1927. In 1971, a group of interested persons, including actress Helen Hayes, purchased it from the Archdiocese of New York and undertook restoration. The work was overseen by architect Walter Knight Sturges, and the chapel was re-dedicated as an ecumenical site in 1977.[24]

In the 1900s Our Lady of Loretto had mission stations in Garrison and Manitou. The cornerstone of the present church was laid in 1906. The organ incorporates portions of five post-Civil War ranks of pipes believed to have been built by Levi Stuart.[25] The Grove, also known as Loretto Rest, is a historic house located on Grove Court in Cold Spring. It was built as the estate of Frederick Lente, surgeon at the nearby Foundry and later a founder of the American Academy of Medicine in the mid-19th century. The Italian-villa design, popular at the time, was by the prominent architect Richard Upjohn. After death of Mrs. Lente in 1901, it was inherited by Patrick Connick, pastor of Our Lady of Loretto, and became a convalescent home for priests run by the Sisters of Charity. It was later converted into a convent for Franciscan nuns who taught at the parish school, which operated from 1913 to 1977. In 2008 the building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Saint Mary's in the Highlands

The early Episcopal congregation was served by clergy from St. Philips in Garrison. In 1835 the Rev. Charles Lucke conducted services in Cold Spring. He was followed by Rev. Henry L. Storrs and then Rev. Edward C. Bull. In 1839 a number of English immigrants arrived to work at the Foundry. As members of the Church of England, the need for a formal Episcopal parish became apparent. Messrs Kemble and Parrott were chosen church wardens. Rev. Ebenezer Williams was the first pastor.[21]

The parish was incorporated on June 19, 1840. It is generally believed that the name of the parish was suggested by Parrott's wife Mary, who provided the funds to build the church. On June 30, Bishop Benjamin T. Onderdonk of the Episcopal Diocese of New York laid the cornerstone. That same year Rev. Williams recorded twenty-five burials, noting the prevalence of sickness in the area. The Gothic brick church, with a tower whose bell weighed 910 pounds, was completed in 1841 and consecrated in November. Besides Bishop Onderdonk, also in attendance were: Rev. John Brown of St. George's Newburgh, Rev. Moses Marcey of St. Peter's Peekskill, and Rev. Freeman Clarkson of St. Anna's of Fishkill Landing.[21]

A second larger church was built in 1867. Designed in the Victorian Gothic style by architect and vestry member George Edward Harney, and built under the direction of Sylvanus Ferris on land donated by Robert Parker Parrott, it was completed the following year. It was constructed of gray granite donated by the estate of Frederick P. James. Situated at Main and Chestnut Streets, the church has a commanding view overlooking the village and river. The consecration of the church took place in a ceremony led by Bishop Horatio Potter on July 23, 1869. On that day the great bell in the tower, weighing 1,100 pounds, rang for the first time.[26]

Initially Sunday school classes were conducted in the basement of the church which proved too dark, damp and cold for the children. Harney and Ferris completed St. Mary's Parish Hall in 1874. The hall was the gift of Frederick and Julia James to honor the memory of their sons Frederick and Julian, who both served in the Union army during the Civil War.[26]

A fire broke out in the north transept in July 1961 causing significant damage to the church's roof and interior. The chancel roof was completely destroyed and the transept roofs were badly burned. The original organ and most of the stained glass were lost while the furniture fortunately survived with little damage. The church was restored within a year and rededicated in 1962 by Bishop Horace W. B. Donegan. Walter Jago of Sleepy Hollow Restoration, the restoration architect, donated the "Christ Window" above the Floyd-Jones altar in the south transept.[26]

Rectors

- 1839-1844 The Rev'd Father Ebenezer William

- 1844-1861 The Rev'd Father Robert Shaw

- 1861-1865 The Rev'd Father Charles W. Morrill

- 1865-1871 The Rev'd Father Mytton Maury

- 1872-1874 The Rev'd Father Charles Carroll Parsons

- 1874-1891 The Rev'd Father Isaac Van Winkle

- 1891-1895 The Rev'd Father Ernest Clement Saunders

- 1895-1946 The Rev'd Father Elbert Floyd-Jones

- 1946-1949 The Rev'd Father H. Anton Griswold

- 1949-1950 The Rev'd Father Frederick Q. Schaeffer

- 1950-1961 The Rev'd Father Edward S. Gray

- 1961-1992 The Rev'd Father John G. Mills

- 1993-1998 The Rev'd Father William J. Barnds

- 2002-present The Rev'd Dr. Shane Scott-Hamblen[26]

Media

Cold Spring has two weekly newspapers: The Highlands Current, founded in 2010, published on Friday and the Putnam County News & Recorder, founded in 1868, published on Wednesday.

Schools

Cold Spring is home to the Haldane Central School District. The school is located at 11 Craigside Drive and teaches students grades K-12.[27] The school received a blue ribbon award in 2017 from the U.S. Department of Education.[28]

Summer camps

Surprise Lake Camp is located just outside Cold Spring when it was the last stop on the Hudson River Line in 1902. The camp is a Jewish Summer Camp funded by the UJA Federation of New York. Some famous campers were Eddie Cantor, Larry King, Neil Diamond, Jerry Stiller, Neil Simon, and many more.[29]

Notable people

- Gail Brown, actress

- Bob Duffy, college and pro basketball player, born in Cold Spring

- Scotti Hill, rock musician

- Albert L. Ireland, United States Marine

- Sean Patrick Maloney - Congressman from New York's 18th Congressional District

- Jean Marzollo, writer, creator of the I Spy book series

- Sarah P. Monks, California naturalist, born in Cold Spring

- Charlie Plummer, American actor, grew up in Cold Spring

- Emily Warren Roebling, first female field engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge

- Gouverneur K. Warren, American military commander during the Civil War and hero of the Battle of Gettysburg

See also

References

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2020 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Cold Spring village, Putnam County, New York". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- Smith, J. Michael (Spring 2010). "Wappinger Kinship Associations: Daniel Nimham's Family Tree". The Hudson River Valley Review A Journal of Regional Studies. 26 (2): 82–84.

- Humphrey, Thomas J. (1998). ""Extravagant Claims" and "Hard Labour:" Perceptions of Property in the Hudson Valley, 1751-1801". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 65: 141–166. ISSN 0031-4528.

- ""A History of Cold Spring", Village of Cold Spring, New York". Archived from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- Levine, David. "History and Preservation of the West Point Foundry in Cold Spring", Hudson Valley Magazine, December 24, 2013

- "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original (Searchable database) on July 1, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2015. Note: This includes Lynn Beebe Weaver (November 1972). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: West Point Foundry" (PDF). Retrieved November 1, 2015. and Accompanying photographs

- ""History and Heritage in Cold Spring-on-Hudson", Cold Spring Merchants Association". Archived from the original on January 30, 2017. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- Grace, Trudie A., Around Cold Spring, Arcadia Publishing, 2011 ISBN 9780738575971

- "A Brief History ...", Cold Spring Fire Company No.1

- "Funeral procession for a Ku Klux Klan member, held in Cold Spring, Putnam County, New York, 1920s.", New York Public Library

- Gosden, Steve. "Pete Seeger", EcoTopia

- "Julia L. Butterfield Memorial Library". Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- "About | Magazzino Italian Art". magazzino.art. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- "Garrison couple turns private art collection into Magazzino". The Poughkeepsie Journal. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- "Museum Visitor Information | Magazzino Italian Art". magazzino.art. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- "STONECROP GARDENS – 81 Stonecrop Lane – Cold Spring New York 10516". stonecrop.org. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Cold Spring village, New York". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- Floyd-Jones, Elbert. St. Mary's Church in the Highlands, Frank B. Howard, Poughkeepsie, 1920

- Burtsell, Richard Lalor. "The Roman Catholic Church", Clearwater, Alphonso Trumpbour. The History of Ulster County, New York, W. J. Van Deusen, 1907 - Ulster County (N.Y.) p. 421

- Lafort, Remigius. The Catholic Church in the United States of America, Vol. 3: The Province of Baltimore and the Province of New York, Section 1: Comprising the Archdiocese of New York and the Diocese of Brooklyn, Buffalo and Ogdensburg. (New York City: The Catholic Editing Company, 1914), p.400

- "History", Chapel Restoration

- "Church of Our Lady of Loretto", Gluck Pipe Organs

- ""History", The Episcopal Church of St Mary-in-the-Highlands". Archived from the original on December 19, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- haldaneschool.org

- "Four schools earn National Blue Ribbon awards".

- "Surprise Lake Camp's website". Surprise Lake Camp.