Colin Meads

Sir Colin Earl Meads KNZM MBE (3 June 1936 – 20 August 2017) was a New Zealand rugby union player. He played 55 test matches (133 games), most frequently in the lock forward position, for New Zealand's national team, the All Blacks, from 1957 until 1971.

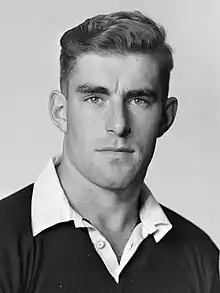

Meads in 1956 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Birth name | Colin Earl Meads | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of birth | 3 June 1936 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Place of birth | Cambridge, New Zealand | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date of death | 20 August 2017 (aged 81) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Place of death | Te Kuiti, New Zealand | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.92 m (6 ft 3+1⁄2 in) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 102 kg (225 lb) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| School | Te Kuiti High School | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notable relative(s) | Stan Meads (brother) Rhonda Wilcox (daughter) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rugby union career | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Meads is widely considered one of the greatest players in history. Nicknamed 'Pinetree' due to his physical presence, he was an icon within New Zealand rugby, and was named the country's Player of the Century at the NZRFU Awards in 1999.

Early life and family

Colin Earl Meads was born to Vere Meads and Ida Meads (née Gray) on 3 June 1936, in the town of Cambridge in the Waikato region.[1] His father Vere was a descendant of early settlers Joseph Meads and Ann Meads (née Coates), who emigrated to New Zealand from England in 1842. Vere's grandfather Zachariah Meads was among the first British children to be born in Te Aro, Wellington, in 1843, and his grandmother Elizabeth Meads (née Lazare) was the daughter of an Irish minister who had educated freed slaves on the island of Mauritius before emigrating to Wanganui. Vere and his wife raised their five children on a sheep farm near Te Kuiti. Meads credited the farming lifestyle for his strong physique and high level of fitness.[2] Meads' brother Stanley Meads was also a noted rugby player, playing 30 matches as an All Black. In 11 matches Stanley and Colin locked the All Black scrum.[3]

Meads and his wife Verna had five children:[4] Karen Stockman, Kelvin Meads, Rhonda Wilcox (who represented New Zealand in the Silver Ferns netball team),[5] Glynn 'Pinecone' Meads (who also played and managed rugby for provincial side King Country)[6] and youngest daughter Shelley Mitchell (who played for the New Zealand women's basketball team).[5] Meads raised his family on a farm on the outskirts of Te Kuiti and continued to live in the area until his death in 2017.[7]

Rugby career

Meads played his club rugby throughout his career for Waitete R.F.C in Te Kuiti.[8] He played his first game for King Country in 1955 against Counties, at the age of 19. He had a memorable game, scoring a try, and even a drop-goal (an unusual feat for a lock).[9] He would play a further 138 games for the province.[6]

In 1955 Meads was also selected for the New Zealand under 21 side which toured Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). He "played all eight matches, scored three tries and was recognised by the Rugby Almanack as one of the 1955 season's most promising players."[10] In 1956 Meads played in national trials and was selected for the North Island team as a loose forward, but was considered too young to play for the All Blacks against the Springboks.[11]

Meads was selected for the 1957 tour of Australia. He played in ten matches and made his test debut, against the Wallabies. He played both tests, scoring a try in the second. Although normally a lock, he played at flanker and number 8, and even wing (from where he scored a try), as the All Black team was strong on locks.[10] From 1957 until 1971 Meads was effectively an automatic pick for the All Blacks, missing selection for just two series; the British & Irish Lions in 1959 and Australia in 1962.[11] There are differing accounts of how he acquired his nickname "Pinetree". Roger Boon believes he was the first to come up with the name in 1955.[12][13] Alternatively, when he toured Japan in the New Zealand Under-23 team in 1958 teammate Ken Briscoe gave him the nickname and it stuck.[3]

He was named captain of the All Blacks 11 times,[14] his first in a 23–9 victory over the Combined Services during the 1963–64 tour of Britain.[11] His captaincy debut for the All Blacks in a test match came in his final series against the Lions in 1971. His final international game ended in a 14–14 draw, giving the Lions a 2–1 series victory, their only series win over the All Blacks.[11] He seriously injured his back in a Land Rover accident at the end of the year and never played for the All Blacks again.[3] Meads recovered enough to continue playing for King Country for two more years before retiring, amassing a total of 361 first class matches, a record that stood for 42 years.[11]

His strength and high threshold for pain became legendary — best illustrated when in a game against Eastern Transvaal in South Africa, in which he emerged from a particularly vicious ruck with his arm dangling horribly, with an obvious fracture, yet completed the match. When the doctor cut away his shirt and confirmed the break, Meads muttered, "At least we won the bloody game."[15] He missed the first two Tests, but returned for the third with his still broken arm held together by a thin guard.[16] Another incident occurred when Meads was kicked in the head, causing a large gash. The All Blacks doctor at the time wanted to take him to hospital so they could use anaesthetic, but Meads ordered him to do it right there in the dressing room.[16]

He also had the reputation of being a "hard man" and "an enforcer". Benoit Dauga, the player Meads thought had kicked him in the head ended up with a broken nose.[17][18] South African center John Gainsford once tried to challenge Meads, who proceeded to hold his wrists in a grip that was "like being held in a band of steel" and simply said "Don't bother, son."[14] Meads considered the Welsh player Rhys Williams and Irishman Willie John McBride just as hard as himself.[19] However, he considered the "one-eyed Springbok" Martin Pelser as his toughest opponent.[20][21]

Meads was involved in some controversial incidents. In 1967, he was sent off by Irish referee Kevin D. Kelleher for dangerous play against Scotland at Murrayfield, becoming only the second All Black suspended in a test match at the time.[22][23] The British newspaper The Daily Telegraph said of the incident that 'For one with Meads' worldwide reputation for robust play, this was rather like sending a burglar to prison for a parking offence.'[24][23]

In Australia he is notorious for having ended the career of Ken Catchpole by wrenching Catchpole's leg while he was pinned down, tearing his hamstring off the bone and severely rupturing his groin muscles.[25][26] Meads says he was just trying to put him on the ground and did not realise his other leg was pinned. Years later he was invited to a dinner in Catchpole's honour, but was warned off by the organisers saying he would get booed off the stage. Meads saw that as more of a reason why he should attend and did so without receiving any boos.[19]

After retirement

After retiring as a player in 1973, Meads became chairman of the King Country union, and spent time selecting and coaching the now-defunct North Island rugby team. In 1986 he was elected to the national selection panel, but was fired later in the year for acting as coach to the unauthorised New Zealand Cavaliers tour of apartheid South Africa, where the All Blacks were no longer allowed to tour.[11] In 1992 he was elected to the New Zealand Rugby Union council and remained there for four years.[11] In 1994 and 1995 he was All Blacks manager, which included the 1995 Rugby World Cup.[11][14] He was uncompromising in this role, not afraid to let loose at his players when they played poorly.[16]

Despite his retirement from rugby, Meads remained a familiar face to many New Zealanders. He was a frequent public speaker at events,[11] donating money raised to buy a farm for people with intellectual disabilities.[14] He also appeared on television advertising products ranging from tanalised fence posts to finance companies. He was seen by many as the public face of Provincial Finance, he described the company as "solid as, I'd say" in an advertisement, and was later criticised when it went bankrupt. He regretted doing the ad and was sorry so many people lost money when it failed.[27] Despite this Meads was named the third most trusted New Zealander after Victoria Cross holder Willie Apiata and triple Olympic gold medallist Peter Snell in 2008.[14]

In 2007 the Meads sold their 102-hectare (250-acre) sheep farm so they could move into Te Kuiti.[27]

In August 2016 it was announced that Meads had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, following several months of illness.[28] He died on 20 August 2017, as a result of cancer.[29] As a mark of respect many New Zealanders placed rugby balls outside the front doors of their homes.[30]

Honours and tributes

Meads is regarded by many as New Zealand's greatest ever rugby player, and was named Player of the Century at the NZRFU Awards dinner in 1999.[11] He is a member of both the World Rugby Hall of Fame and the New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame, and was a member of the International Rugby Hall of Fame before its merger with the World Rugby Hall in 2014.[11] The International Rugby Hall of Fame considers him to have been 'the most famous forward in world rugby throughout the 1960s'.[24]

Meads was considered by many to be a tough, uncompromising, loyal and humble person.[33] At 1.92 m (6 ft 3+1⁄2 in) tall and weighing 100 kilograms (220 lb), he was a similar size to many other players of the era. He had a large physical presence though, being very strong and having a high level of fitness. Meads credited this to growing up and working on a farm.[3]

In the 1971 New Year Honours, Meads was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for services to rugby.[34] He was appointed a Distinguished Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (CNZM) for services to rugby and the community, in the 2001 New Year Honours.[35] In the 2009 Special Honours, following the restoration of titular honours by the New Zealand government, Meads accepted redesignation as a Knight Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (KNZM).[36][37] On 19 June 2017, during the then-ongoing British & Irish Lions tour, a statue of Meads was unveiled in the Te Kuiti town centre. Despite his ongoing battle with cancer, Meads attended and spoke at the unveiling.[38]

One of the other trophies contested in New Zealand's domestic competition, the Heartland Championship, is named the Meads Cup in his honour.[39] Rugby writer Lindsay Knight wrote that "As a sporting legend Meads is New Zealand's equivalent of Australia's Sir Donald Bradman or the United States of America's Babe Ruth."[10]

References

- Colin Meads – All Black: Alex Veysey. 1974

- Gallagher, Brendon (2 June 2005). "Rugged life moulded Meads into greatest All Black". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008.

- "Obituary: Rugby legend Sir Colin Meads remembered, after losing battle with cancer". 1 NEWS NOW. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "'We will miss him terribly': All Blacks legend Sir Colin Meads dies after battle with pancreatic cancer". NZ Herald. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "PressReader.com - Digital Newspaper & Magazine Subscriptions". www.pressreader.com.

- "Colin Meads: Biography". New Zealand History.

- "Teary eyed in Te Kuiti: locals pay respects to All Black colossus Sir Colin Meads in hometown". Stuff. 20 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "Meads not yet ready to lay down for McCaw". The Roar. 25 October 2012.

- "Colin Earl Meads". ESPN scrum. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- Knight, Lindsay. "Colin Meads". allblacks.com. New Zealand Rugby Museum. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "FACTBOX-Rugby-All Blacks great Colin Meads". U.K. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- Boult, Kris (17 August 2017). "How Sir Colin Meads became a Pinetree". Stuff.

- Veysey, Alex (1974). Colin Meads All Black. London Collins.

- "Colin Meads remembered: 'One of New Zealand's special treasures'". NZ Herald. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "An oral history of the time Colin Meads played rugby with a broken arm". The Spinoff. 21 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Today's All Blacks pale in comparison to the 'tree". The Guardian. 3 November 2002. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Today's All Blacks pale in comparison to the 'tree", 4 November 2002, The Guardian

- "The quotes and tales that summed up the great Sir Colin Meads". Stuff. 20 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "The Pinetree fella". The Guardian. 9 November 2002. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "The quotes and tales that summed up the great Sir Colin Meads". Stuff. 20 August 2017.

- "Strongman Pelser dies". Rugby365.

- Bradley, Grant (3 August 2011). "Moments of Infamy: Meads sent off". New Zealand Herald.

- "Sending a burglar to prison for a parking offence". Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Colin Meads". International Rugby Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013.

- "Parliament of New South Wales Debates: Sydney Cricket and Sports Ground Amendment Bill, 7 June 2006". Archived from the original on 7 September 2008.

- "All Black great Colin Meads dead". NewsComAu. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Sir Colin Meads obituary - the great Pinetree has fallen". Stuff. 20 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Sir Colin Meads diagnosed with pancreatic cancer". The New Zealand Herald. 11 August 2013.

- "Legendary former All Black Sir Colin Meads has died aged 81, say reports". Newshub. 20 August 2017.

- "Subscribe | theaustralian". www.theaustralian.com.au. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- Moorby, Caitlin (24 August 2017). "Thousands expected at hometown farewell for Sir Colin Meads". Stuff. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- "CEMETERY SNAPSHOT REPORT". Waitomo District Council. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- "All Blacks legend Colin Meads dies at 81". Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "No. 45264". The London Gazette (3rd supplement). 1 January 1971. p. 41.

- "New Year honours list 2001". Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 30 December 2000. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Special Honours List (12 August 2009) 118 New Zealand Gazette 2691

- "Colin 'Pinetree' Meads to take knighthood". Stuff.co.nz. NZPA. 12 May 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- Hamilton, Tom (19 June 2017). "'Welcome to Meadsville' – New Zealand honours Sir Colin Meads". ESPN (UK). Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- "King Country rugby – Regional rugby | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 20 August 2017.