Collard (plant)

Collard is a group of certain loose-leafed cultivars of Brassica oleracea, the same species as many common vegetables including cabbage and broccoli. Collard is generally described as part of the Acephala (kale) cultivar group,[1][2] but gets its own variety as Brassica oleracea var. viridis.[3] The name "collard" comes from the word "colewort" (a medieval term for non-heading brassica crops).[4][5]

| Collard | |

|---|---|

A bundle of collard greens | |

| Species | Brassica oleracea |

| Cultivar group | Acephala Group |

| Origin | Greece |

| Cultivar group members | Many; see text. |

The plants are grown as a food crop for their large, dark-green, edible leaves, which are cooked and eaten as vegetables. Collard greens have been eaten over centuries, with evidence showing that the ancient Greeks cultivated the plant.[6]

Description

The term collard has been used to include many non-heading Brassica oleracea crops. While American collards are best placed in the Viridis crop group,[3] the Acephala cultivar group is also used ("without a head" in Greek) referring to a lack of close-knit core of leaves (a "head") like cabbage does, making collards more tolerant of high humidity levels and less susceptible to fungal diseases.[7] The plant is a biennial where winter frost occurs; some varieties may be perennial in warmer regions. It has an upright stalk, often growing over two feet tall and up to six feet for the Portuguese cultivars. Popular cultivars of collard greens include 'Georgia Southern', 'Vates', 'Morris Heading', 'Blue Max', 'Top Bunch', 'Butter Collard' (couve manteiga), couve tronchuda, and Groninger Blauw.[3] In Africa it is commonly known as sukuma (East Africa), muriwo or umBhida (Southern Africa).

Cultivation

The plant is commercially cultivated for its thick, slightly bitter, edible leaves. They are available year-round, but are tastier and more nutritious in the cold months, after the first frost. For best texture, the leaves are picked before they reach their maximum size, at which stage they are thicker and are cooked differently from the new leaves. Age does not affect flavor.

Flavor and texture also depend on the cultivar; the couve manteiga and couve tronchuda are especially appreciated in Brazil and Portugal. The large number of varieties grown in the United States decreased as people moved to towns after World War II, leaving only five varieties commonly in cultivation. However, seeds of many varieties remained in use by individual farmers, growers and seed savers as well as within US government seed collections.[8] In the Appalachian region, cabbage collards, characterized by yellow-green leaves and a partially heading structure are more popular than the dark-green non-heading types in the coastal South.[9] There have been projects from the early 2000s to both preserve seeds of uncommon varieties and also enable more varieties to return to cultivation.[10]

Nutritional information

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 137 kJ (33 kcal) |

5.6 g | |

| Sugars | 0.4 g |

| Dietary fiber | 4 g |

0.7 | |

2.7 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 48% 380 μg42% 4513 μg6197 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 3% 0.04 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 9% 0.11 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 4% 0.58 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 4% 0.22 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 10% 0.13 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 4% 16 μg |

| Vitamin C | 22% 18 mg |

| Vitamin E | 6% 0.9 mg |

| Vitamin K | 388% 407 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 14% 141 mg |

| Iron | 9% 1.13 mg |

| Magnesium | 6% 21 mg |

| Manganese | 24% 0.51 mg |

| Phosphorus | 5% 32 mg |

| Potassium | 2% 117 mg |

| Sodium | 1% 15 mg |

| Zinc | 2% 0.23 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 90.2 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

Raw collard greens are 90% water, 6% carbohydrates, 3% protein, and contain negligible fat (table). Like kale, collard greens contain substantial amounts of vitamin K (388% of the Daily Value, DV) in a 100-gram (3.5 oz) serving. Collard greens are rich sources (20% or more of DV) of vitamin A, vitamin C, and manganese, and moderate sources of calcium and vitamin B6.[11] A 100-gram (3+1⁄2-ounce) reference serving of cooked collard greens provides 137 kilojoules (33 kilocalories) of food energy. Some collard cultivars may be abundant sources of aliphatic glucosinolates, such as glucoraphanin.[12]

Culinary use

East Africa

Collard greens are known as sukuma in Swahilli and are one of the most common vegetables in East Africa.[13] Sukuma is mainly lightly sauteed in oil until tender, flavoured with onions and seasoned with salt, and served either as the main accompaniment or as a side dish with meat or fish. In Congo, Tanzania and Kenya (East Africa), thinly sliced collard greens are the main accompaniments of a popular dish known as sima or ugali (a maize flour cake).

Southern and Eastern Europe

Collards have been cultivated in Europe for thousands of years with references to the Greeks and Romans back to the 1st Century.[14] In Montenegro, Dalmatia and Herzegovina, collard greens, locally known as raštika or raštan, were traditionally one of the staple vegetables. It is particularly popular in the winter, stewed with smoked mutton (kaštradina) or cured pork, root vegetables and potatoes.[15] Known in Turkey as kara lahana ("dark cabbage"), it is a staple in the Black Sea area.

United States

Collard greens are a staple vegetable in Southern U.S. cuisine.[16][17][18] They are often prepared with other similar green leaf vegetables, such as spinach, kale, turnip greens, and mustard greens in the dish called "mixed greens". Typically used in combination with collard greens are smoked and salted meats (ham hocks, smoked turkey drumsticks, smoked turkey necks, pork neckbones, fatback or other fatty meat), diced onions, vinegar, salt, and black pepper, white pepper, or crushed red pepper, and some cooks add a small amount of sugar. Traditionally, collards are eaten on New Year's Day, along with black-eyed peas or field peas and cornbread, to ensure wealth in the coming year.[16] Cornbread is used to soak up the "pot liquor", a nutrient-rich collard broth. Collard greens may also be thinly sliced and fermented to make a collard sauerkraut that is often cooked with flat dumplings. Landrace collard in-situ genetic diversity and ethnobotany are subjects of research for citizen-science groups.[10]

During slavery, collards were one of the most common plants grown in kitchen gardens and were used to supplement the rations provided by plantation owners.[19] Greens were widely used because the plants could last through the winter weather and could withstand the heat of a southern summer even more so than spinach or lettuce.[19]

Broadly, collard greens symbolize Southern culture and African-American culture and identity. For example, jazz composer and pianist, Thelonious Monk, sported a collard leaf in his lapel to represent his African-American heritage.[20] In President Barack Obama's first state dinner, collard greens were included on the menu. Novelist and poet Alice Walker used collards to reference the intersection of African-American heritage and black women.[20] There have been many collard festivals that celebrate African-American identity, including those in Port Wentworth, Georgia (since 1997), East Palo Alto, California (since 1998), Columbus, Ohio (since 2010), and Atlanta, Georgia (since 2011). In 2010, the Latibah Collard Greens Museum opened in Charlotte, North Carolina.[20]

Many explorers in the late nineteenth century have written about the pervasiveness of collards in Southern cooking particularly among black Americans. In 1869, Hyacinth, a traveler during the Civil War, for example, observed that collards could be found anywhere in the south.[21] In 1972, another observer, Stearns, echoed that sentiment claiming that collards were present in every black Southerner's garden.[21] In 1883, a writer commented on the fact that there is no word or dish more popular among poorer whites and blacks than collard greens.[21] The collard sandwich—consisting of fried cornbread, collard greens, and fatback—is a popular dish among the Lumbee people in Robeson County, North Carolina.[22]

Brazil and Portugal

In Portuguese and Brazilian cuisine, collard greens (or couve) are a common accompaniment to fish and meat dishes. They make up a standard side dish for feijoada, a popular pork and beans-style stew.[23] These Brazilian and Portuguese cultivars are likely members of a distinct non-heading cultivar group of Brassica oleracea, specifically the Tronchuda Group.

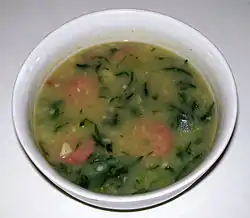

Thinly-sliced collard greens are also a main ingredient of a popular Portuguese soup, the caldo verde ("green broth"). For this broth, the leaves are sliced into strips, 2–3 mm (3⁄32–1⁄8 in) wide (sometimes by a grocer or market vendor using a special hand-cranked slicer) and added to the other ingredients 15 minutes before it is served.

Kashmir Valley

In Kashmir,[24][25] collard greens (haakh) are included in most meals.[26] Leaves are harvested by pinching in early spring when the dormant buds sprout and give out tender leaves known as kaanyil haakh. When the extending stem bears alternate leaves in quick succession during the growing season, older leaves are harvested periodically. In late autumn, the apical portion of the stem is removed along with the whorled leaves. There are several dishes made with haakh. A common dish eaten with rice is haak rus, a soup of whole collard leaves cooked simply with water, oil, salt, green chilies and spices.

Zimbabwe

In Zimbabwe, collard greens are known as umbhida in Ndebele and muriwo in Shona. Due to the climate, the plant thrives under almost all conditions, with most people growing it in their gardens.[27] It is commonly eaten with sadza (ugali in East Africa, pap in South Africa, and polenta in Italy) as part of the staple food.[28] Umbhida is normally wilted in boiling water before being fried and combined with sautéed onions or tomato. Some (more traditionally, the Shona people) add beef, pork and other meat to the umbhida mix for a type of stew.[29] Most people eat umbhida on a regular basis in Zimbabwe, as it is economical and can be grown with little effort in home gardens.[30]

Pests

The sting nematode, Belonolaimus gracilis and the awl nematode, Dolichodorus spp. are both ectoparasites that can injure collard. Root symptoms include stubby or coarse roots that are dark at the tips. Shoot symptoms include stunted growth, premature wilting, and chlorosis (Nguyen and Smart, 1975). Another species of the sting worm, Belonolaimus longicaudatus, is a pest of collards in Georgia and North Carolina (Robbins and Barker, 1973). B. longicaudatus is devastating to seedlings and transplants. As few as three nematodes per 100 g (3.5 oz) of soil when transplanting can cause significant yield losses on susceptible plants. They are most common in sandy soils (Noling, 2012).

The stubby root nematodes Trichodorus and Paratrichodorus attach and feed near the tip of collard's taproots. The damage caused prevents proper root elongation leading to tight mats that could appear swollen, therefore resulting in a "stubby root" (Noling, 2012).

Several species of the root knot nematode Meloidogyne spp. infest collards. These include: M. javanica, M. incognita and M. arenaria. Second-stage juveniles attack the plant and settle in the roots. However, infestation seems to occur at lower populations compared to other cruciferous plants. Root symptoms include deformation (galls) and injury that prevent proper water and nutrient uptake. This could eventually lead to stunting, wilting and chlorosis of the shoots (Crow and Dunn, 2012).

The false root knot nematode Nacobbus aberrans has a wide host range of up to 84 species including many weeds. On Brassicas it has been reported in several states, including Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, Montana, South Dakota, and Kansas (Manzanilla-López et al., 2002). As a pest of collards, the degree of damage is dependent upon the nematode population in the soil.

Some collard cultivars exhibit resistance to bacterial leaf blight incited by Pseudomonas cannabina pv. alisalensis (Pca).[31]

See also

References

- Farnham, Mark W. (May 1996). "Genetic Variation among and within United States Collard Cultivars and Landraces as Determined by Randomly Amplified Polymorphic DNA Markers". Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 121 (3): 374–379. doi:10.21273/jashs.121.3.374. ISSN 0003-1062.

- Quiros, Carlos F.; Farnham, Mark W. (2011), Schmidt, Renate; Bancroft, Ian (eds.), "The Genetics of Brassica oleracea", Genetics and Genomics of the Brassicaceae, Plant Genetics and Genomics: Crops and Models, New York, NY: Springer, pp. 261–289, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-7118-0_9, ISBN 978-1-4419-7118-0, retrieved 2020-11-28

- Pelc, Sandra E.; Couillard, David M.; Stansell, Zachary J.; Farnham, Mark W. (2015). "Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Collard Landraces and their Relationship to Other Brassica oleracea Crops". The Plant Genome. 8 (3): eplantgenome2015.04.0023. doi:10.3835/plantgenome2015.04.0023. ISSN 1940-3372. PMID 33228266. S2CID 55772782.

- "collard". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "Greeks and Romans Grew Kale and Collards". Texas A&M Agricultural Extension. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- "Greeks and Romans Grew Kale and Collards | Archives | Aggie Horticulture". Texas A&M University. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- "Brassica oleracea var. acephala". Floridata. 2007-02-06. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- Freeman, Debra (19 March 2021). "The Farmers and Gardeners Saving the South's Signature Green". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- "Collards". University of Alabama Press. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- "The Heirloom Collard Project". The Heirloom Collards Project. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

- Farnham, Mark W.; Lester, Gene E.; Hassell, Richard (2012-08-01). "Collard, mustard and turnip greens: Effects of genotypes and leaf position on concentrations of ascorbic acid, folate, β-carotene, lutein and phylloquinone". Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 27 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2012.04.008. ISSN 0889-1575.

- Stansell, Zachary; Cory, Wendy; Couillard, David; Farnham, Mark (2015). "Collard landraces are novel sources of glucoraphanin and other aliphatic glucosinolates". Plant Breeding. 134 (3): 350–355. doi:10.1111/pbr.12263. ISSN 1439-0523.

- Swegarden, Hannah; Stelick, Alina; Dando, Robin; Griffiths, Phillip D. (2019). "Bridging Sensory Evaluation and Consumer Research for Strategic Leafy Brassica (Brassica oleracea) Improvement". Journal of Food Science. 84 (12): 3746–3762. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.14831. ISSN 1750-3841. PMID 31681987. S2CID 207897390.

- "Greeks and Romans Grew Kale and Collards". Aggie Horticulture. Texas A & M Agrilife Extension. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Liliana Pavicic and Gordana Pirker-Mosher Best of Croatian Cooking, p. 137, at Google Books

- Vitrano A (2011-01-01). "Dine wise on New Year's Day, Certain foods could bring you luck". South Carolina NOW. Archived from the original on 2013-02-01. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- "Collard Greens Shortage Threatens New Year's Day Good Luck Recipe". Newsweek. 28 December 2018. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Farnham, M. W.; Davis, E. H.; Morgan, J. T.; Smith, J. P. (2008). "Neglected landraces of collard (Brassica oleracea L. var. viridis) from the Carolinas (USA)". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 55 (6): 797–801. doi:10.1007/s10722-007-9284-8. ISSN 0925-9864. S2CID 9123036.

- Wortman, Stefanie (2012). "Greens". Southwest Review. 97 (3): 400–407. ISSN 0038-4712. JSTOR 43473220.

- H., Davis, Edward (2015). Collards: a southern tradition from seed to table. The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-8765-5. OCLC 906925404. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Davis, Edward H.; Morgan, John T. (2005). "Collards in North Carolina". Southeastern Geographer. 45 (1): 67–82. doi:10.1353/sgo.2005.0004. ISSN 1549-6929. S2CID 130521748.

- Shestack, Elizabeth (March 2015). "The Collard Sandwich is a Robeson County Delicacy". Our State. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- Esposito, Shaylyn (2014-06-13). "How to Make Feijoada, Brazil's National Dish, Including a Recipe From Emeril Lagasse". Smithsonian.com.

- Khan, S. H.; Ahmad, N.; Jabeen, N.; Chattoo, M. A.; Hussain, K. (June 2010). "Biodiversity of kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala L.) in Kashmir Valley" (PDF). The Asian Journal of Horticulture. 5 (1): 208–210. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Mir, Shakir (13 October 2017). "Kashmiri Haakh". Kashmir Life. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Reshi, Marryam (3 November 2015). "Haakh or Collard Greens". Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "The "African" vegetable that lifts the weak". The Zimbabwean. 2006-05-25. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- "Food in Zimbabwe - Zimbabwean Food, Zimbabwean Cuisine - traditional, diet, history, common, meals, staple, rice, people, make". Food by Country.

- "Pork Bones Haifiridzi". 21 May 2017.

- "The "African" vegetable that lifts the weak". The Zimbabwean. 2006-05-25. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- Branham, Sandra E.; Farnham, Mark W.; Robinson, Shane M.; Wechter, W. Patrick (2018-06-01). "Identification of Resistance to Bacterial Leaf Blight in the U.S. Department of Agriculture Collard Collection". HortScience. 53 (6): 838–841. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI12347-17. ISSN 0018-5345.

External links

Media related to Brassica oleracea var. viridis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Brassica oleracea var. viridis at Wikimedia Commons