Brussels sprout

The Brussels sprout is a member of the Gemmifera cultivar group of cabbages (Brassica oleracea), grown for its edible buds. The leaf vegetables are typically 1.5–4.0 cm (0.6–1.6 in) in diameter and resemble miniature cabbages. The Brussels sprout has long been popular in Brussels, Belgium, from which it gained its name.[1]

| Brussels sprout | |

|---|---|

Brussels sprouts (cultivar unknown) | |

| Species | Brassica oleracea |

| Cultivar group | Gemmifera Group |

| Origin | Low Countries (year unknown) |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 179 kJ (43 kcal) |

8.95 g | |

| Sugars | 2.2 g |

| Dietary fibre | 3.8 g |

0.3 g | |

3.48 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 5% 38 μg4% 450 μg1590 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 12% 0.139 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 8% 0.09 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 5% 0.745 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 6% 0.309 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 17% 0.219 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 15% 61 μg |

| Choline | 4% 19.1 mg |

| Vitamin C | 102% 85 mg |

| Vitamin E | 6% 0.88 mg |

| Vitamin K | 169% 177 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 4% 42 mg |

| Iron | 11% 1.4 mg |

| Magnesium | 6% 23 mg |

| Manganese | 16% 0.337 mg |

| Phosphorus | 10% 69 mg |

| Potassium | 8% 389 mg |

| Sodium | 2% 25 mg |

| Zinc | 4% 0.42 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 86 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

Etymology

Although native to the Mediterranean region with other cabbage species, Brussels sprouts first appeared in northern Europe during the 5th century; they were later cultivated in the 13th century near Brussels, Belgium, from which they derived their name.[1][2] Its group name Gemmifera (or lowercase and italicized gemmifera as a variety name) means gemmiferous (bud-producing).

Cultivation

Forerunners to modern Brussels sprouts were probably cultivated in Ancient Rome. Brussels sprouts as they are now known were grown possibly as early as the 13th century in what is now Belgium. The first written reference dates to 1587. During the 16th century, they enjoyed a popularity in the southern Netherlands that eventually spread throughout the cooler parts of Northern Europe.

Brussels sprouts grow in temperature ranges of 7–24 °C (45–75 °F), with highest yields at 15–18 °C (59–64 °F).[2] Fields are ready for harvest 90 to 180 days after planting. The edible sprouts grow like buds in helical patterns along the side of long, thick stalks of about 60 to 120 cm (24 to 47 in) in height, maturing over several weeks from the lower to the upper part of the stalk. Sprouts may be picked by hand into baskets, in which case several harvests are made of five to 15 sprouts at a time, or by cutting the entire stalk at once for processing, or by mechanical harvester, depending on variety. Each stalk can produce 1.1 to 1.4 kg (2.4 to 3.1 lb), although the commercial yield is about 900 g (2 lb) per stalk.[2] Harvest season in temperate zones of the northern latitudes is September to March, making Brussels sprouts a traditional winter-stock vegetable. In the home garden, harvest can be delayed as quality does not suffer from freezing. Sprouts are considered to be sweetest after a frost.[3]

Brussels sprouts are a cultivar group of the same species as broccoli, cabbage, collard greens, kale, and kohlrabi; they are cruciferous (they belong to the family Brassicaceae; old name Cruciferae). Many cultivars are available; some are purple in color, such as 'Ruby Crunch' or 'Red Bull'.[4] The purple varieties are hybrids between purple cabbage and regular green Brussels sprouts developed by a Dutch botanist in the 1940s, yielding a variety with some of the red cabbage's purple colors and greater sweetness.[5]

Contemporary Brussels sprouts

In the 1990s, Dutch scientist Hans van Doorn identified the chemicals that make Brussels sprouts bitter: sinigrin and progoitrin.[6] This enabled Dutch seed companies to cross-breed archived low-bitterness varieties with modern high-yield varieties, over time producing a significant increase in the popularity of the vegetable.[7]

Europe

In Continental Europe, the largest producers are the Netherlands, at 82,000 metric tons, and Germany, at 10,000 tons. The United Kingdom has production comparable to that of the Netherlands, but its crop is generally not exported.[8]

Mexico

Second to the Netherlands in export volume is Mexico where the climate allows nearly year-round production.[9] The Baja region is the main supplier to the US market, but produce also comes from the Mexicali, San Luis and coastal areas.

U.S.

Production of Brussels sprouts in the United States began in the 18th century, when French settlers brought them to Louisiana.[2] The first plantings in California's Central Coast began in the 1920s, with significant production beginning in the 1940s. Currently, several thousand acres are planted in coastal areas of San Mateo, Santa Cruz, and Monterey counties of California, which offer an ideal combination of coastal fog and cool temperatures year-round. The harvest season lasts from June through January.

Most U.S. production is in California,[10] with a smaller percentage of the crop grown in Skagit Valley, Washington, where cool springs, mild summers, and rich soil abounds, and to a lesser degree on Long Island, New York.[11] Total US production is around 32,000 tons, with a value of $27 million.[2]

About 80 to 85% of U.S. production is for the frozen food market, with the remainder for fresh consumption.[11] Once harvested, sprouts last 3–5 weeks under ideal near-freezing conditions before wilting and discoloring, and about half as long at refrigerator temperature.[2] North American varieties are generally 2.5–5 cm (0.98–1.97 in) in diameter.[2]

Nutrients, phytochemicals and research

Raw Brussels sprouts are 86% water, 9% carbohydrates, 3% protein, and negligible fat. In a 100 gram reference amount, they supply high levels (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of vitamin C (102% DV) and vitamin K (169% DV), with more moderate amounts of B vitamins, such as vitamin B6, as well as folate; essential minerals and dietary fiber exist in moderate to low amounts (table).

Brussels sprouts, as with broccoli and other brassicas, contain sulforaphane, a phytochemical under basic research for its potential biological properties. Although boiling reduces the level of sulforaphane, steaming, microwave cooking, and stir frying do not cause a significant loss.[12]

Consuming Brussels sprouts in excess may not be suitable for people taking anticoagulants, such as warfarin, since they contain vitamin K, a blood-clotting factor. In one incident, eating too many Brussels sprouts led to hospitalization for an individual on blood-thinning therapy.[13]

Uses

Culinary

The most common method of preparing Brussels sprouts for cooking begins with cutting the buds off the stalk. Any surplus stem is cut away, and any loose surface leaves are peeled and discarded. Once cut and cleaned, the buds are typically cooked by boiling, steaming, stir frying, grilling, slow cooking, or roasting. This process is done for up to 45 minutes and to ensure even cooking throughout, buds of a similar size are usually chosen. Some cooks make a single cut or a cross in the center of the stem to aid the penetration of heat. The cross cut may, however, be ineffective, with it being commonly believed to cause the sprouts to be waterlogged when boiled.[14]

Overcooking renders the buds gray and soft, and they then develop a strong flavor and odor that some dislike for its garlic- or onion-odor properties.[10][15] The odor is associated with the glucosinolate sinigrin, a sulfur compound having characteristic pungency.[15] For taste, roasting Brussels sprouts is a common way to cook them to enhance flavor.[15][16] Common toppings or additions include Parmesan cheese and butter, balsamic vinegar, brown sugar, chestnuts, or pepper.

Gallery

Brussels sprouts ready for harvest

Brussels sprouts ready for harvest_(2).jpg.webp) Harvested Brussels sprouts on stalks

Harvested Brussels sprouts on stalks Fresh Brussels sprouts being transported from a farm in Wesselburenerkoog, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany

Fresh Brussels sprouts being transported from a farm in Wesselburenerkoog, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany Brussels sprouts on stalks at a farmers' market in Massachusetts

Brussels sprouts on stalks at a farmers' market in Massachusetts Brussels sprouts on stalk at a supermarket

Brussels sprouts on stalk at a supermarket Brussels sprouts removed from the stalk and placed in a net type bag

Brussels sprouts removed from the stalk and placed in a net type bag Brussels sprout sliced in half

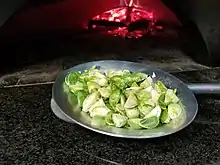

Brussels sprout sliced in half.jpg.webp) Brussels sprouts roasted over a fire

Brussels sprouts roasted over a fire

References

- Olver, Lynne (11 April 2011). "Food Timeline: Brussels sprouts". The Food Timeline. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- "Brussel Sprouts". UGA.edu. College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, University of Georgia. Archived from the original on 13 September 2007. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- Crockett, James Underwood (1977). Crockett's Victory Garden. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 187. ISBN 0-316-16120-9.

- Rose, Linda (2017). "Brussels sprouts". sonomamg.ucanr.edu. Master Gardener Program of Sonoma County, University of California. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Friesema, Felicia (8 February 2013). "What's In Season at the Farmers Market: (The End of) Purple Brussels Sprouts at Weiser Family Farms". L. A. Weekly. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "Brussels: a bittersweet story". Society of Chemical Industry. 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- Charles, Dan (30 October 2019). "From Culinary Dud To Stud: How Dutch Plant Breeders Built Our Brussels Sprouts Boom". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Retrieved 30 March 2020 – via NPR.org.

- Illert, S. (2004). "The Small Market Study: Brussels Sprouts". Gemuse Munchen. 40 (12): 56–58.

- "Top Brussels Sprouts Exports by Country". World's Top Exports. WorldsTopExports.com.

- Zeldes, Leah A (9 March 2011). "Eat this! Brussels sprouts, baby cabbages for St. Patrick's Day". Dining Chicago. Chicago's Restaurant & Entertainment Guide, Inc. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- "Crop Profile for Brussels Sprouts in California". ipmcenters.org. United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- "Research Says Boiling Broccoli Ruins Its Anti Cancer Properties" (Press release). University of Warwick. 15 May 2007.

- Pettit, Stephen J; Japp, Alan G; Gardner, Roy S (10 December 2012). "The hazards of Brussels sprouts consumption at Christmas". The Medical Journal of Australia. 197 (11): 661–662. doi:10.5694/mja12.11304. PMID 23230944. S2CID 42292011.

- "Brussels sprouts recipes". BBC Food. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- Ortner, E.; Granvogl, M. (2018). "Thermally induced generation of desirable aroma-active compounds from the glucosinolate sinigrin". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 66 (10): 2485–2490. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01039. PMID 28629219.

- "Abernethy Elementary chef taking her lessons to White House". The Oregonian. 1 June 2010.

External links

- Brassica oleracea gemmifera – Plants For a Future database entry