Cologne Charterhouse

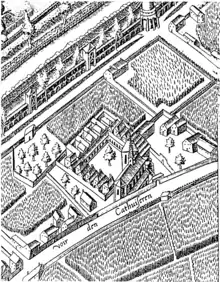

Cologne Charterhouse (German: Kölner Kartause) was a Carthusian monastery or charterhouse established in the Severinsviertel district, in the present Altstadt-Süd, of Cologne, Germany. Founded in 1334, the monastery developed into the largest charterhouse in Germany[1] until it was forcibly dissolved in 1794 by the invading French Revolutionary troops. The building complex was then neglected until World War II, when it was mostly destroyed. The present building complex is very largely a post-war reconstruction. Since 1928, the Carthusian church, dedicated to Saint Barbara, has belonged to the Protestant congregation of Cologne.

Antecedents and foundation

Prior to the foundation of Cologne Charterhouse there were already 113 charterhouses throughout Europe, of which 30 were in Germany,[2] but none in the Archdiocese of Cologne. Walram of Jülich, who became Archbishop of Cologne in 1332, had become acquainted before his elevation with the Carthusians in France, and had come to respect them. His desire to found a Carthusian monastery in Cologne was doubtless reinforced by the examples of the nearby bishoprics of Mainz and Trier, who had already founded charterhouses in 1312 and 1321/1322 respectively. Over and above that, Saint Bruno, the founder of the Carthusian Order, had been born in Cologne, and for this reason also it seemed appropriate to establish a Carthusian presence in his home-town. The foundation occurred in a period of mystic piety, which brought about a golden age for the Carthusians generally,[3] in which increasingly the enclosed Carthusian monks settled also in urban environments without giving up their enclosed and secluded way of life.

On 6 December 1334, Archbishop Walram issued the foundation charter of Cologne Charterhouse:

- We, Walram, by the grace of God Archbishop of the holy church in Cologne and Arch-chancellor of the Holy Empire for Italy, do make known to all men who read these presents that we, for the salvation of our soul and for the sake of the especial favour with which we look upon the Carthusian order, have made the following ordinance, so that this order might grow in our diocese and that the memory of us should endure within this order, namely: for the building of the monastic church and of a monastery of this order in our city of Cologne we grant hereby to the Prior [...] the income of 100 malter of wheat annually... Given in Cologne on St. Nicholas the Bishop's Day in the year 1334.[4]

From 1389, the Sencte Mertinsvelt ("St. Martin's Field") in the south of the district of St. Severin was given over for the use of the Carthusians: according to the legend, Saint Martin himself instructed Bishop Walram in a dream to do so. On this plot of land, there had been, since about the beginning of the 13th century, a little chapel dedicated to Saint Barbara, which was now renovated for Carthusian use with the financial assistance of the Cologne patrician families of Scherffgin and Lyskirchen. In addition, the families of Lyskirchen and Overstolz made gifts of extra agricultural land, and in that way the material prerequisites for the commencement of the life of the order were assured.

This was the last monastic foundation in Cologne until the 16th century.

Early years

In early February 1335, the first six Carthusian monks, with their leader (Rektor) Johannes of Echternach, moved from Mainz to Cologne. They retained the dedication to Saint Barbara from the extant chapel, but gave the relics several decades later to the neighbouring Franciscans.

The Carthusians' first task was to construct the most essential buildings for the accommodation of the new community. Thanks to further gifts and endowments the new charterhouse was able to be formally incorporated into the order as early as 1338. In the same year, Johannes of Echternach was replaced on the general chapter by Heinrich Sternenberg as the first prior. (The first prior of the Cologne Charterhouse to be elected by the community itself was Stephan of Koblenz).

Economically the charterhouse started off on a weak foundation. Archbishop Walram had promised more to the charterhouse than he was able to deliver: his budget was diminished by the expenses of military conflict, and the monks were thus entirely dependent on the continuing generosity of the wealthy of Cologne. Their individual endowments and the charterhouse's consequent obligations were recorded in benefactors' books, which until 2009 were preserved in the Historical Archive of the City of Cologne.[5]

There were also bitter wrangles that lasted for years over prebends and other sources of income with the nearby St. Severin's Abbey (Stift St. Severin), whose income was affected by the new charterhouse. Much information about the resulting agreements with St. Severin's has survived, which throws light on the material pressures of monastic life:

- "5. The burials of strangers within the monastery walls are to be limited to two, or at the most, three, a year. Of presents or bequests of movable goods which fall to the monastery as a result of such burials, the treasurer of St. Severin's shall receive one third".[6]

When Archbishop Walram died in 1349, the situation became even more precarious, but the following years saw the charterhouse grow in prestige and thus attract an increasing number of affluent novices, which made it wealthier, but also over-burdened the available residential space and the small chapel. Gifts and endowments for the building of a new church are recorded from 1354, and in the same year Charles IV exempted the charterhouse from payment of duty on building materials, which seems to point to construction beginning around this time.[7] The legacy of Canon Johannes of Brandenburg, who in 1365 left the monks an adjoining plot of land, provided the space for a new chapter house and library as well as the continued expansion of the church.

Also in 1365 Henry Eger of Kalkar (1328–1408) entered the charterhouse, becoming after three years the prior of Monnikhuizen Charterhouse near Arnhem, then of the newly-established Vogelsang Charterhouse, and finally of Koenigshoffen Charterhouse near Strasbourg before retiring to Cologne as a simple monk, where he died in 1408. Leaving aside his administrative importance, he was a prominent theologian who exercised much influence on the development of the Devotio Moderna movement. His reputation was such that he was often credited with the authorship of The Imitation of Christ.[8]

By the beginning of the 15th century the crisis of the beginning had finally been overcome. The charterhouse had scarcely been affected by either the Western Schism or the Black Death. In 1393, the new church was consecrated, which in its essential features has lasted until today, and the charterhouse entered a period of prosperity which was to make it one of the richest monasteries in Cologne.

Development and golden age

The building and dedication of the Carthusian church took place during the period of office of Prior Hermann of Deventer. After the dedication an unusually large number of altars were set up in the church, which was magnificently furnished and decorated: this was extremely unusual for a Carthusian church, in which normally only a single altar was permitted. An explanation for this is the atypically high number of monks here who were also ordained priests and therefore obliged to celebrate Mass daily.[9]

Besides further extensions to the monastery church, including the Angel Chapel and the Lady Chapel, progress continued to be made to the conventual buildings, supported as always by endowments. It is presumed that the first modest cells and buildings were of wood and plaster, and were gradually replaced by a refectory, cloister and 25 cells of worked stone.

The monks lived a strictly contemplative life in which work on books and manuscripts was of especial importance. Through gifts of books and the entry to the community of wealthy and educated men who brought entire libraries with them, St. Barbara's possessed by the middle of the 15th century one of the largest collections of manuscripts in medieval Cologne.[10] Each cell was equipped with a workshop where the monk could copy writings: unlike in other monasteries, the copyists were not required to work in the library, but could take the manuscripts they were copying to their cells.

The Carthusians of Cologne must also during this period have risen in prestige within their order, as their prior Roland von Luysteringen was sent as the Carthusian representative to the Council of Constance, where regrettably he died of the plague. Pope Martin V freed Cologne Charterhouse of episcopal jurisdiction in 1425, so that from then on it answered directly to the popes.

This flourishing monastic life experienced an abrupt interruption when a catastrophic fire on 6 November 1451 totally destroyed the chapter house and adjacent buildings, including the entire library and its contents, except for those manuscripts which happened to be in individual cells for copying.

Restoration

Generous gifts to the charterhouse – particularly from Peter Rinck, Rector of Cologne University – made it possible to rebuild the chapter house and library within two years. It took a great deal longer to recover from the financial and intellectual loss of the books and manuscripts. The charterhouse authorities addressed themselves to the task of making good the losses with great energy and single-mindedness. New manuscripts were acquired outright or borrowed to be copied either by the monastery's own monks or even by hired copyists. Prior Hermann of Appeldorn (1457–1472) counts as the driving force during this period of reconstruction; at his death he was honoured for his financial acumen as "reformator et recuperator huius domus". While he was prior not only was the library largely restored but also a new gatehouse was built and an altarpiece painted by Meister Christoph for the Angels' Altar in the charterhouse church.

In 1459, even before the charterhouse had begun to recover financially, Prior Johannes Castoris was appointed by Pope Pius II as abbot of the Benedictine St. Pantaleon's Abbey in Cologne, which was seriously in debt. This extraordinary step of seconding a non-Benedictine head of house in order to reform St. Pantaleon's and bring it back onto the right track, is an indication of the high degree of trust within the church that the Carthusians in Cologne had come to enjoy through their strict adherence to the discipline of their order and way of life.[11]

The successors to Appeldorn and Castoris followed their lead, and under their direction the charterhouse made further progress. Under Johann of Bonn (1476–1507) there was further substantial construction work, particularly in the service buildings such as the kitchen and the store rooms, but also in additions to the decoration of the church. By the end of the 15th century the library had grown again to comprise some 500 volumes, and the church had gained two new triptychs by the Master of the Saint Bartholomew Altarpiece, now considered masterpieces of European painting, and displayed in the Wallraf-Richartz Museum,[12] as well as the monumental cycle of paintings, made for display in the small cloister, by the Master of the Legend of Saint Bruno (speculatively dated around 1486).[13]

Reformation

Presumably in part as a result of the monastery's experience of the loss of their library and the need to replace it, by the early 16th century the charterhouse had not only a printing-press but also a book bindery. At this time the building complex took its final shape, with the completion in 1511 of the sacristy, of the great cloister, presumed to have been completed in 1537, and the cross in the burial ground.

Of decisive importance in the first half of the 16th century and the early Protestant Reformation was the tenure of office as prior of Peter Blommeveen of Leiden, who had entered the charterhouse in 1489 after studying at Cologne University, and became its prior in 1507. While he was in office the founder of the Carthusian Order, Bruno of Cologne, was canonised, and like other charterhouses the Cologne Charterhouse received some of his relics, which had been re-discovered in 1502. Aegidius Gelenius lists in his catalogue of the treasures of the Cologne Charterhouse, published in 1645, among many other relics "two pieces of the skull of Saint Bruno".[14]

Under Blommeveen a small extension was added to the Kartäuserwall which bounded the monastery complex on the south, so that women might also seek the prior's spiritual counsel, as entrance to the monastery was strictly forbidden to them.

A theologian of great distinction associated around this period with the charterhouse was Johann Justus of Landsberg (1489–1539), known generally as Lanspergius, who made his first profession in 1509 and later became sub-prior. In 1530 he was appointed prior of Vogelsang Charterhouse near Jülich but his health deteriorated nd he returned in 1534 in his old role as sub-prior, dying in 1539. He was a highly regarded theologian, particularly influential in his work on the theology of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and was the first to publish the mystical writings of Saint Gertrude of Helfta.[15]

In 1517 Martin Luther published his Ninety-five Theses and thus launched the Protestant Reformation and a period of destruction and unrest throughout Germany, particularly in many monasteries. Many monks left their monasteries, including many Carthusians, although only one charterhouse – the Nuremberg Charterhouse – was dissolved at this period. Cologne Charterhouse stayed true to its strict principles. Blommeveen published some writings in defence of Catholicism and the works of the orthodox theologian Denis the Carthusian (Dionysius van Leeuw). Since the Carthusians, on account of their vow of silence, did not preach, their contribution to the defence of traditional Catholic belief was necessarily a written one.

Blommeveen's successor Gerhard Kalckbrenner financially supported the Jesuits when they opened a house in Cologne (1544) – the first Jesuit community in Germany[16] – and ensured the settlement in Cologne of the well-known beguine and mystic Maria of Oisterwijk, with whom he was on friendly terms. Her works, and those of the mystic Gertrude the Great, were both printed by Cologne Charterhouse. Also closely associated with the Cologne Carthusians at this time was the Jesuit preacher Petrus Canisius.

In the event Cologne remained almost entirely Catholic and little influenced by the efforts of the reformers. Luther's writings were publicly burnt, as in 1529 were the reformers Adolf Clarenbach and Peter Fliesteden. The attempt by Archbishop Hermann von Wied in 1541/42 to introduce the Protestant Reformation into the archdiocese met with great resistance and also failed.

The centuries before secularisation

During the rest of the 16th century and the whole of the 17th, the monastery limited its building activities to repair and restoration, and the further decoration of the church. The Carthusian Johannes Reckschenkel from Trier lived in here in the late 16th century and became prior in 1580. Besides producing several writings he also made some paintings in the sacristy and provided the monks' cells with improved sanitation. Donations fell off, as the strict piety of the Carthusians was out of fashion, and people preferred to support other orders. Nevertheless, Cologne Charterhouse with 23 monks in about 1630 was the largest Carthusian community in Germany.[17] and was still able to afford new altars, windows and choir stalls for the Baroque refurbishment of the church interior. Some roofs were repaired, cells replaced and in about 1740 a new enlarged conventual building of three wings was erected on the street front.

The charterhouse library by about 1600 had again become one of the largest and best in Cologne. A catalogue of 1695 lists 6,600 volumes, and in the 18th century there were almost 8,000. The 18th century however also saw sales of manuscripts, creating gaps in the collection.

The end, not only of the library, but of the charterhouse itself, was signalled on 6 October 1794, when the French troops occupied Cologne.

A few weeks after their arrival, on 23 October 1794, Prior Martin Firmenich was ordered to vacate the charterhouse within 24 hours, as it was required for use as a military hospital. Despite desperate efforts to save the most valuable pieces of the church treasures, looting, theft and vandalism ensured that the irreplaceable collections of archives, books and artworks were irretrievably dispersed.

Until 1802, when all religious houses were finally dissolved in the secularisation, the Carthusian monks lived in temporary accommodation in what is now Martinstraße 19–21, made available to them by the Bürgermeister of Cologne, Johann Jakob von Wittgenstein. Thereafter they had either to look for livings as parish priests or to support themselves in whatever way they could.

Prussian administration

Unlike many other monastic buildings during the years following secularisation, the premises of Cologne Charterhouse, despite its use as a military hospital, remained largely unaltered. In 1810, the buildings passed into the possession of the City of Cologne, who however exchanged them in 1816 with the Prussian military authorities for other plots of land. It was from this point onwards that major destruction began. The conventual building was again put to use as a military hospital, the remains of the cloisters as a laundry and kitchen, and the church and chapter house as an arsenal, stable and carriage house. By 1827, there remained only 12 bays of the great cloister. The altars and the rood screen disappeared, windows were bricked up and new ones broken through the walls as required. Rubble was tipped down the wells, and broken stones from the crypts and the graveyard used to block the church windows.[18] The significance of the charterhouse not only in religious terms but also in terms of architecture and art history was totally lost to public awareness until the very end of the 19th century.

It was not until 1894 that Ludwig Arntz, master builder of the cathedral, drew public attention to the importance and sorry condition of the monastery complex in an essay in the Zeitschrift für christliche Kunst.[19] This had little practical result: during World War I the buildings were used yet again for the accommodation of wounded soldiers, and otherwise allowed to stand empty.

The Carthusian church becomes Protestant

After World War I the buildings passed from Prussian ownership to that of the Reichsvermögensverwaltung. Once their use as a military hospital had ended discussions began about their future use. At this time there was a dispute concerning the use of the Romanesque former abbey church of St. Pantaleon, which since 1818 had served as the Protestant church of the Prussian garrison and had also been used by the civilian Protestant population of predominantly Catholic Cologne. After the withdrawal of the Prussian military, the Catholics demanded the return of the church from the Ministry of War, which was granted them by ministerial decree in 1921. For the loss of the use of the church the Protestant community was to receive compensation of 200,000 Paper Marks, but as the great 1920s German inflation was just taking hold this was not regarded as adequate. It had already been suggested in 1919 by Regierungspräsident Philipp Brugger that the unused Carthusian church should be given to the Protestants, and the idea was now resurrected. The continuing inflation prolonged the repair and conversion works until 1928, when at last the former Carthusian church was re-dedicated, on 16 September, as a Protestant church. The former conventual building was taken over by the Finance Department of Köln-Süd.

World War II: destruction and reconstruction

In the first years of World War II, the charterhouse escaped significant damage from air raids, but the last major air attack of 2 March 1945 caused great destruction: the church, chapter house, cloisters and prior's house were severely damaged, and the external wall on to the street known as the Kartäusergasse was totally destroyed, as were the conventual buildings.

Among the ruins a makeshift structure for religious services was cobbled together for the use of a Protestant population increased by the arrival of displaced persons and refugees. The first service in the Trümmerkirche ("ruin church") was held on 19 August 1945. The church and parts of its surroundings were gradually rebuilt in three main stages up to 1953. The destroyed external wall on the Kartäusergasse was rebuilt by the members of the congregation. The conventual building used before the war by the finance office was also reconstructed and in 1960 occupied by the Protestant church administration of the city (evangelischer Stadtkirchenverband Köln).

From 1955, parts of the two cloisters were restored: a complete reconstruction was out of the question for financial reasons, which also delayed the reconstruction of the chapter house, eventually completed in 1985.[20]

Church - west side

Church - west side Church - main portal

Church - main portal Monastery garden, cloister and chapter house

Monastery garden, cloister and chapter house Refectory

Refectory

Notes

- Rita Wagner: Eine kleine Geschichte der Kölner Kartause St. Barbara, in: Die Kölner Kartause um 1500. Eine Reise in unsere Vergangenheit. Exhibition guide, Cologne 1991, p. 48

- Christel Schneider, Die Kölner Kartause von ihrer Gründung bis zum Ausgang des Mittelalters, Köln 1932, p. 13

- Rainer Sommer: Die Kölner Kartause 1334–1928 in: Die Kartause in Köln. Festschrift, Köln 1978, p. 19

- quoted [in German] by Rita Wagner: Eine kleine Geschichte...", p. 30: Wir, Walram, durch Gottes Gnade Erzbischof der heiligen Kirche von Köln und Erzkanzler des heiligen Reiches für Italien, tun allen, die diese Urkunde lesen, kund, daß wir zum Heile unserer Seele und um der besonderen Gunst willen, mit der wir dem Kartäuserorden zugetan sind, folgende Anordnung getroffen haben, damit dieser Orden in unserer Diözese wachse und in diesem Orden immerfort unser gedacht werde: Für den Bau der Klosterkirche und eines Klosters dieses Ordens in unserer Stadt Köln weisen wir hiermit dem Prior […] die Einkünfte von 100 Maltern Weizen jährlich zu […] Gegeben in Köln, im Jahre 1334, am Tag des hl. Bischofs Nikolaus.

- the building of the Historical Archive of the City of Cologne collapsed on 3 March 2009 and it is as yet (May 2014) not known which of the archives held in it have been destroyed

-

- „5. werden die jährlichen Beerdigungen von Fremden innerhalb der Klostermauern auf zwei, höchstens drei festgesetzt. Von Geschenken oder Vermächtnissen, die sich auf bewegliche Güter beziehen, die dem Kloster infolge einer Beerdigung zufallen, soll der Thesaurar von St. Severin den dritten Teil erhalten.“ quoted in Christel Schneider: Die Kölner Kartause, p. 62

- Ludwig Arntz: Kartäuserkirche – Baugeschichte, in: Paul Clemen, Die Kunstdenkmäler der Rheinprovinz, Band VII. Abt. III: Die kirchlichen Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Köln, Köln 1934, p. 142

- Robert Haaß: "Eger von Kalkar, Heinrich". In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3428001850, p. 327f. (online version)

- Rita Wagner: Eine kleine Geschichte… p. 35

- Rita Wagner: Eine kleine Geschichte… p. 37

- Rita Wagner, Eine kleine Geschichte… p. 40

- Rainer Sommer: Die Kölner Kartause 1334–1928, p. 29. (WRM 179 and WRM 180)

- Frank Günter Zehnder: Altkölner Malerei. Kataloge des Wallraf-Richartz-Museums, vol XI. Stadt Köln, 1990

- "zwei Teile des Schädels des heiligen Bruno" – Die Kölner Kartause um 1500. Aufsatzband. Köln 1991, p. 15

- Karl Hausberger: "Landsberg, Johannes". In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 13, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1982, ISBN 342800194X, p. 513 (online version)

- Kalckbrenner had developed a strong friendship with Ignatius of Loyola and the Cologne Charterhouse became a generous financial sponsor of several Jesuit works, including the German College of Rome.

- Rita Wagner: Eine kleine Geschichte…, p. 48

- Ludwig Arntz, as below

- Ludwig Arntz, 1894: Kartäuserkirche – Baugeschichte in Zeitschrift für christliche Kunst, reprinted in Paul Clemen, Die kirchlichen Denkmäler der Stadt Köln, 1934

- Ulrich Bergfried: Glanz, Zerstörung, Wiederaufbau. 20 harte Jahre für die Kölner Kartause. In: Rainer Sommer, Die Kartause in Köln

References

- Clemen, Paul (ed), 1934: Die Kunstdenkmäler der Rheinprovinz. Siebenter Band, III. Abteilung: Die kirchlichen Denkmäler der Stadt Köln. Düsseldorf: L. Schwann

- Schäfke, Werner (ed), 1991: Die Kölner Kartause um 1500. Kölnisches Stadtmuseum ISBN 3-927396-37-0

- Schäfke, Werner (ed), 1991: Die Kölner Kartause um 1500 (exhibition guide). Köln: Kölnisches Stadtmuseum ISBN 3-927396-38-9

- Schneider, Christel, 1932: Die Kölner Kartause von ihrer Gründung bis zum Ausgang des Mittelalters. Veröffentlichungen des Historischen Museums der Stadt Köln, Heft II. Bonn: Peter Hanstein Verlagsbuchhandlung

- Sommer, Rainer (ed), 1978: Die Kartause in Köln. Festschrift der evangelischen Gemeinde Köln zum 50. Jahrestag der Einweihung der Kartäuserkirche in Köln zur evangelischen Kirche am 16. September 1978. Cologne 1978

External links

- Kartäuserkirche Köln official website (in German)