Isca Augusta

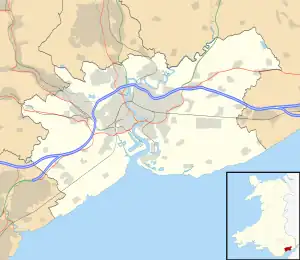

Isca, variously specified as Isca Augusta or Isca Silurum, was the site of a Roman legionary fortress and settlement or vicus, the remains of which lie beneath parts of the present-day suburban town of Caerleon in the north of the city of Newport in South Wales. The site includes Caerleon Amphitheatre and is protected by Cadw.

| Isca Augusta | |

|---|---|

| Newport, Wales | |

Caerleon amphitheatre | |

Isca Augusta Location in Wales Newport | |

| Coordinates | 51.6103°N 2.9589°W |

| Grid reference | ST336909 |

Headquarters of the Legion "II Augusta", which took part in the invasion under Emperor Claudius in 43, Isca is uniquely important for the study of the conquest, pacification and colonisation of Britannia by the Roman army. It was one of only three permanent legionary fortresses in later Roman Britain and, unlike the other sites at Chester and York, its archaeological remains lie relatively undisturbed beneath fields and the town of Caerleon and provide a unique opportunity to study the Roman legions in Britain. Excavations continue to unearth new discoveries;[1] in the late 20th century a complex of very large monumental buildings outside the fortress between the River Usk and the amphitheatre was uncovered. This new area of the canabae was previously unknown.[2]

Name

The Brythonic name Isca means "water" and refers to the River Usk. The suffix Augusta appears in the Ravenna Cosmography and was an honorific title taken from the legion stationed there. The place is commonly referred to as Isca Silurum to differentiate it from Isca Dumnoniorum and because it lay in the territory of the Silures tribe. However, there is no evidence that this form was used in Roman times. The later name, Caerleon, is derived from the Welsh for "fortress of the legion".

Foundation and history

Isca was founded in 74 or 75 during the final campaigns by Governor Sextus Julius Frontinus against the fierce native tribes of western Britain, notably the Silures in South Wales who had resisted the Romans’ advance for over a generation.

Isca became the headquarters of the Legion II Augusta based in the large fortress of typical legionary "playing-card" shape and built initially with an earth bank and timber palisade. It remained their headquarters until at least 300 AD. The interior was fitted out with the usual array of military buildings: a headquarters building, legate's residence, tribunes' houses, hospital, large bath house, workshops, barrack blocks, granaries and, unusually, a large amphitheatre.

At this time there were four legions in Britain out of a total of about 30 legions in the Empire, making Britain one of the most heavily militarised provinces due to its frontier status and hostile neighbours.[3] Each legion consisted of over 5,000 heavily armed and highly disciplined professional soldiers who enlisted in the army for at least 20 years. As the backbone of the army, legionaries were the conquerors and builders of the Roman Empire who brought with them foreign ideas, practices and traditions that would change the society and culture of Britain forever.

An inscription of Trajan gives a date of AD99/100 for the replacement of the fortress walls, when the original earth and timber ramparts of the fortress were strengthened by the addition of a stone revetment at the front. This "composite" rampart consisted of a stone wall 5 to 5½ feet thick, backed by a clay bank and fronted by a single ditch

By 120 AD, detachments or vexillations of the legion were needed elsewhere in the province and Isca became more of a military base than a garrison. However, it is thought that each cohort still maintained a presence at the fortress. When Septimius Severus seized power in the 190s, he had Isca refurbished and the legion were in residence rebuilding themselves after heavy losses on the Continent. Further restoration took place under Caracalla, when the south-west gate was rebuilt, the amphitheatre remodelled and barrack blocks re-roofed and otherwise repaired. The legion may have been called away to fight for one of the many emperors claiming power in the late 3rd century. Although most of the fort lay empty, a 'caretaker' squad are thought to have maintained the facilities and there was reoccupation and rebuilding work as late as the 270s. The main military structures are thought to have finally been demolished by the usurpers, Carausius or Allectus, when the legion was needed to repel a potential invasion from the Continent. The stone from Isca may have been used for building defences on the south coast. There may still have been an occasional military presence as late as the early 4th century, but the fortress was probably later taken over by the people of the surrounding vicus. The basilica of the baths was used as a cattle pen.

Recent finds suggest Roman occupation of some kind as late as 380.[6][7][8]

Christian martyrs

According to the Gildas (followed by Bede), Roman Caerleon was the site of two early Christian martyrdoms in Britain, at the same time as that of Saint Alban the first British martyr, who was killed in the Roman city of Verulamium (beside modern-day St Albans). He writes:

God, therefore, who wishes all men to be saved, and who calls sinners no less than those who think themselves righteous, magnified his mercy towards us, and, as we know, during the above-named persecution, that Britain might not totally be enveloped in the dark shades of night, he, of his own free gift, kindled up among us bright luminaries of holy martyrs, whose places of burial and of martyrdom, had they not for our manifold crimes been interfered with and destroyed by the barbarians, would have still kindled in the minds of the beholders no small fire of divine charity. Such were Saint Alban of Verulamium, Aaron and Julius, citizens of the City of the Legions, and the rest, of both sexes, who in different places stood their ground in the Christian contest.

This city of the legions is identified with Caerleon, rather than Chester, because there were two medieval chapels there dedicated to each of these martyrs. They were probably executed in 304, during the religious persecutions of Diocletian's reign. However, these chapels may have been founded as a result of Bede's writings and cannot be dated archaeologically any earlier than the church of St John's in Chester which is also situated next to an amphitheatre.

Amphitheatre

Because of its rounded form, the unexcavated amphitheatre was known to locals as "King Arthur's Round Table", but there is no known connection. An initial investigation in 1909 showed the potential for a full-scale excavation of the structure, which began in 1926 and was supervised by Victor Erle Nash-Williams. This revealed, among other things, that the amphitheatre had been built around 80. This (Period I) building was destroyed by fire in the early-second century, and the second (Period II) building erected c. AD 138 was destroyed around sixty years later c. 196/197. It was rebuilt for the third and last time during the campaigns of Severus and Caracalla in Britain c. 197–211. The Period III building finally fell into disuse around the middle of the fourth century at the same time that the Caerleon fortress was evacuated. The latest coin from this site is that of Valens (364–378).[9]

The arena is oval in shape, with eight entrances, and the stadium is thought to have had a capacity of around six thousand spectators, and apart from the usual gladiatorial entertainments, it was probably used for parades, displays and exercises by the garrison of the fortress.

Remains

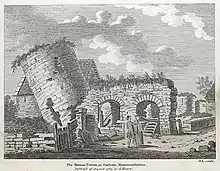

Substantial archeologically excavated Roman remains of the Roman fortress can be seen at Caerleon.

Cadw administers:

- The military amphitheatre, one of the most impressive in Britain

- Part of the military bath house, with the Caerleon Roman Fortress and Baths in situ above it

- Prysg Field Barracks, the only Roman legionary barracks visible in Europe

- The fortress wall, still standing 12 feet (3.7 m) high in places

Legion museum

The National Roman Legion Museum, located in the town, is part of the National Museums and Galleries of Wales. The museum exhibits artifacts and finds from excavations throughout the town and from nearby Burrium (Usk), including Roman currency, weapons, uniform etc.

References

- Knight, Jeremy K (1988). Caerleon Roman Fortress. Cardiff: Cadw.

- "School of History, Archaeology and Religion".

- "The Caerleon canabae: excavations in the civil settlement 1984-90" (2000), Edith Evans, Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

- Roman Legionary Fortresses 27BC-AD378: Duncan Campbell, Osprey Publishing

- Evans, Edith (2004). The Roman fortress of Caerleon and its environs: A framework for research (Report). Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust.

- Isca (Caerleon Roman Fortress) (ID PRN00514g) in the 'SMR' for Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust (GGAT)

- "Priory Field Caerleon Dig 2008 Cardiff University and UCL Dr Peter Guest and Dr Andrew Gardner". Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- "Priory Field Caerleon Dig 2010 Cardiff University and UCL Dr Peter Guest". Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- "Caerleon Dig Blog 2011 Cardiff University Dr Peter Guest".

- "Isca Silvrvm". Archived from the original on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- Caerleon Roman harbour

- Cardiff university video fly-though Archived 2011-12-04 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Cadw - Caerleon Amphitheatre - official site for visiting

- The Caerleon Research Committee

- Caerleon Legionary Fortress page at the Community Archaeology Forum of the Council for British Archaeology

- Caerleon amphitheatre from Gathering the Jewels

- Caerleon on the Roman Britain website