Leicester

Leicester (/ˈlɛstər/ ⓘ LES-tər)[4] is a city, unitary authority area, unparished area and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest city in the East Midlands. Its population was 368,600 in 2021, increased by 38,800 (![]() 11.8%) from around 329,800 in 2011.[5] The greater Leicester urban area had a population of 559,017 in 2021, making it the 11th most populous in England,[6] and the 13th most populous in the United Kingdom.

11.8%) from around 329,800 in 2011.[5] The greater Leicester urban area had a population of 559,017 in 2021, making it the 11th most populous in England,[6] and the 13th most populous in the United Kingdom.

Leicester

City of Leicester | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp)   Clockwise, from top: City Centre & Clock Tower; Leicester Cathedral; Curve Theatre; the Jewry Wall; and National Space Centre | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Shown within Leicestershire | |

Leicester Location within the East Midlands  Leicester Location within the United Kingdom  Leicester Location within Europe | |

| Coordinates: 52°38′04″N 1°07′55″W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | England |

| Region | East Midlands |

| Ceremonial county | Leicestershire |

| Founded | AD c. 47 as Ratae Corieltauvorum |

| City status restored | 1919 |

| Administrative headquarters | Leicester Town Hall (meeting place) and City Hall, Leicester (council offices) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unitary authority |

| • Body | Leicester City Council |

| • Leadership | Mayor and cabinet |

| • Executive | Labour Party |

| • Lord Mayor | George Cole |

| • City Mayor | Peter Soulsby (Lab) |

| Area | |

| • City | 28.3 sq mi (73.3 km2) |

| • Urban | 87 sq mi (225 km2) |

| • Metro | 290 sq mi (750 km2) |

| Elevation | 205 ft (62.5 m) |

| Population (2021[1]) | |

| • City | 368,600 |

| • Density | 12,000/sq mi (4,500/km2) |

| • Urban | 508,916[2] |

| • Urban density | 5,900/sq mi (2,260/km2) |

| • Metro | 836,484[3] |

| • Metro density | 3,070/sq mi (1,185/km2) |

| • Ethnicity (2021) |

|

| Time zone | UTC+0 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (British Summer Time) |

| Postcode areas | |

| Dialling codes | 0116 |

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-LCE |

| ONS code | 00FN (ONS) E06000016 (GSS) |

| OS grid reference | SK584044 |

| NUTS 3 | UKF21 |

| Primary airport | East Midlands Airport (Outside of Leicester) |

| Councillors | 54 |

| MPs | List of MPs |

| Website | leicester.gov.uk |

The city lies on the River Soar and is approximately 90 miles (140 km) north-northwest of London, 33 miles (53 km) east-northeast of Birmingham and 21 miles (34 km) northeast of Coventry. Nottingham and Derby lie around 21 miles to the north and northwest respectively, whilst Peterborough is located 37 miles (60 km) to the east. Leicester is close to the eastern end of the National Forest.[7]

Leicester has a long history extending into ancient times, it was the site of the Roman town of Ratae Corieltauvorum, which was later captured by the Anglo-Saxons, and then by the Vikings who made it one of the Five Boroughs of the Danelaw. Leicester became an important town during the Middle Ages, and then an important industrial and commercial centre in the Victorian age, eventually gaining city status in 1919. Since the mid-20th century, immigration from countries of the British Commonwealth has seen Leicester become an ethnically diverse city, and one of the largest urban centres of the Midlands.

Leicester is at the intersection of two railway lines: the Midland Main Line and the Birmingham to London Stansted Airport line. It is also at the confluence of the M1/M69 motorways and the A6/A46 trunk routes. Leicester Cathedral is home to the tomb of King Richard III who was reburied in the cathedral in 2015 after being discovered nearby in the foundations of the lost Greyfriars chapel, more than 500 years after his death. In sporting terms, Leicester is the home to football club Leicester City and rugby club Leicester Tigers.

Name

The name of Leicester comes from Old English. It is first recorded in Latinised form in the early ninth century as Legorensis civitatis and in Old English itself in an Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 924 as Ligera ceastre (and, in various spellings, frequently thereafter). In the Domesday Book of 1086, it is recorded as Ledecestre.[8]

The first element of the name is the name of a people, the Ligore (whose name appears in Ligera ceastre in the genitive plural form); their name came in turn from the river Ligor (now the River Soar), the origin of whose name is uncertain but thought to be from Brittonic (possibly cognate with the name of the Loire).[8][9][10][11]

The second element of the name is the Old English word ceaster ("(Roman) fort, fortification, town", itself borrowed from Latin castrum).[8]

A list of British cities in the ninth-century History of the Britons includes one Cair Lerion; Leicester has been proposed as the place to which this refers (and the Welsh name for Leicester is Caerlŷr). But this identification is not certain.[12]

Based on the Welsh name (given as Kaerleir), Geoffrey of Monmouth proposes a king Leir of Britain as an eponymous founder in his Historia Regum Britanniae (12th century).[13]

History

Prehistory

Leicester is one of the oldest cities in England, with a history going back at least two millennia.[14] The native Iron Age settlement encountered by the Romans at the site seems to have developed in the 2nd or 1st centuries BC.[15] Little is known about this settlement or the condition of the River Soar at this time, although roundhouses from this era have been excavated and seem to have clustered along roughly 8 hectares (20 acres) of the east bank of the Soar above its confluence with the Trent. This area of the Soar was split into two channels: a main stream to the east and a narrower channel on the west, with a presumably marshy island between. The settlement seems to have controlled a ford across the larger channel. The later Roman name was a latinate form of the Brittonic word for "ramparts" (cf. Gaelic rath and the nearby villages of Ratby and Ratcliffe[16]), suggesting the site was an oppidum. The plural form of the name suggests it was initially composed of several villages.[16] The Celtic tribe holding the area was later recorded as the "Coritanians" but an inscription recovered in 1983 showed this to have been a corruption of the original "Corieltauvians".[17][18] The Corieltauvians are believed to have ruled over roughly the area of the East Midlands.

Roman

It is believed that the Romans arrived in the Leicester area around AD 47, during their conquest of southern Britain.[19] The Corieltauvian settlement lay near a bridge on the Fosse Way, a Roman road between the legionary camps at Isca (Exeter) and Lindum (Lincoln). It remains unclear whether the Romans fortified and garrisoned the location, but it slowly developed from around the year 50 onwards as the tribal capital of the Corieltauvians under the name Ratae Corieltauvorum. In the 2nd century, it received a forum and bathhouse. In 2013, the discovery of a Roman cemetery found just outside the old city walls and dating back to AD 300 was announced.[19] The remains of the baths of Roman Leicester can be seen at the Jewry Wall; recovered artifacts are displayed at the adjacent museum.

Medieval

Knowledge of the town following the Roman withdrawal from Britain is limited. Certainly there is some continuation of occupation of the town, though on a much reduced scale in the 5th and 6th centuries. Its memory was preserved as the Cair Lerion[20] of the History of the Britons.[21] Following the Saxon invasion of Britain, Leicester was occupied by the Middle Angles and subsequently administered by the kingdom of Mercia. It was elevated to a bishopric in either 679 or 680; this see survived until the 9th century, when Leicester was captured by Danish Vikings. Their settlement became one of the Five Burghs of the Danelaw, although this position was short-lived. The Saxon bishop, meanwhile, fled to Dorchester-on-Thames and Leicester did not become a bishopric again until the Church of St Martin became Leicester Cathedral in 1927. The settlement was recorded under the name Ligeraceaster in the early 10th century.[22]

Following the Norman conquest, Leicester was recorded by William's Domesday Book as Ledecestre. It was noted as a city (civitas) but lost this status in the 11th century owing to power struggles between the Church and the aristocracy and did not become a legal city again until 1919.

Geoffrey of Monmouth composed his History of the Kings of Britain around the year 1136, naming a King Leir as an eponymous founder figure.[23] According to Geoffrey's narrative, Cordelia had buried her father beneath the river in a chamber dedicated to Janus and his feast day was an annual celebration.[24]

When Simon de Montfort became Lord of Leicester in 1231, he gave the city a grant to expel the Jewish population[25] "in my time or in the time of any of my heirs to the end of the world". He justified his action as being "for the good of my soul, and for the souls of my ancestors and successors".[26] Leicester's Jews were allowed to move to the eastern suburbs, which were controlled by de Montfort's great-aunt and rival, Margaret, Countess of Winchester, after she took advice from the scholar and cleric Robert Grosseteste.[27] There is evidence that Jews remained there until 1253, and perhaps enforcement of the banishment within the city was not rigorously enforced. De Montfort however issued a second edict for the expulsion of Leicester's Jews in 1253, after Grosseteste's death.[28] De Montfort's many acts of anti-Jewish persecution in Leicester and elsewhere were part of a wider pattern that led to the expulsion of the Jewish population from England in 1290.[29]

During the 14th century, the earls of Leicester and Lancaster enhanced the prestige of the town. Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster and of Leicester founded a hospital for the poor and infirm in the area to the south of the castle now known as The Newarke (the "new work"). Henry's son, the great Henry of Grosmont, 4th Earl of Lancaster and of Leicester, who was made first Duke of Lancaster, enlarged and enhanced his father's foundation, and built the collegiate Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady of The Newarke.[30] This church (a little of which survives in the basement of the Hawthorn Building of De Montfort University) was destroyed during the reign of King Edward VI. It became an important pilgrimage site because it housed a thorn said to be from the Crown of Thorns, given to the Duke by the King of France. The church (described by Leland in the C16th as "not large but exceeding fair") also became, effectively, a Lancastrian mausoleum. Duke Henry's daughter Blanche of Lancaster married John of Gaunt and their son Henry Bolingbroke became King Henry IV when he deposed King Richard II. The Church of the Annunciation was the burial place of Duke Henry, who had earlier had his father re-interred here. Later it became the burial place of Constance of Castile, Duchess of Lancaster (second wife of John of Gaunt) and of Mary de Bohun, first wife of Henry Bolingbroke (Henry IV) and mother of King Henry V (she did not become queen because she died before Bolingbroke became king). John of Gaunt died at Leicester Castle in 1399. When his son became king, the Earldom of Leicester and the Duchy of Lancaster became royal titles (and the latter remains so).

At the end of the War of the Roses, King Richard III was buried in Leicester's Greyfriars Church a Franciscan Friary and Church which was demolished after its dissolution in 1538. The site of that church is now covered by King Richard III Visitor Centre (until 2012 by more modern buildings and a car park). There was a legend his corpse had been cast into the river, while some historians[31] argued his tomb and remains were destroyed during the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. However, in September 2012, an archaeological investigation of the car park revealed a skeleton[32] which DNA testing helped verify to be related to two descendants of Richard III's sister.[33] It was concluded that the skeleton was that of Richard III because of the DNA evidence and the shape of the spine. In 2015 Richard III was reburied in pride of place near the high altar in Leicester Cathedral.

Tudor

On 4 November 1530, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey was arrested on charges of treason and taken from Yorkshire. On his way south to face dubious justice at the Tower of London, he fell ill. The group escorting him was concerned enough to stop at Leicester to rest at Leicester Abbey. There, Wolsey's condition quickly worsened. He died on 29 November 1530 and was buried at Leicester Abbey, now Abbey Park.

Lady Jane Grey, who claimed the English throne for nine days in June 1553, was born at Bradgate Park near Leicester around 1536.[34]

Queen Elizabeth I's intimate and former suitor, Robert Dudley, was given the Earldom of Leicester.

Stuart

After the Union of the Crowns, Prince Charles, later King Charles I, travelled to London with his guardian Alexander Seton. The royal party stayed at Leicester for three days in August 1604 at the townhouse of William Skipwith.[35]

The Corporation of Leicester opposed the efforts of Charles I to disafforest the nearby Leicester Forest, believing them to be likely to throw many of its residents into poverty and need of relief. Sir Miles Fleetwood was sent to commission the disafforestation and division of lands being used in common.[36] Riots destroyed enclosures in spring 1627 and 1628, following a pattern of anti-enclosure disturbances found elsewhere including the Western Rising.[37]

Petitions challenging the enclosures were presented by the Corporation of Leicester and borough residents to the King and Privy Council. They were unsuccessful so petitioned the House of Lords in June 1628 who however supported Fleetwood but asked for proceedings made by the Crown against the rioters to be dropped. Compensation made to the legal residents of the forest was reasonably generous by comparison with other forests. The Corporation of Leicester received 40 acres (16 ha) for relief of the poor.[38]

Civil War

Leicester was a Parliamentarian (colloquially called Roundhead) stronghold during the English Civil War. In 1645, King Charles I of England and Prince Rupert decided to attack the (then) town to draw the New Model Army away from the Royalist (colloquially called Cavaliers) headquarters of Oxford. Royalist guns were set up on Raw Dykes and, after an unsatisfactory response to a demand for surrender, the assault began at 3pm on 30 May 1645 by a Royalist battery opposite the Newarke. The town – which only had approximately 2,000 defenders opposed to the Royalist Army of approximately 10,000 combatants – was sacked on 31 May 1645, and hundreds of people were killed by Rupert's cavalry. One witness said, "they fired upon our men out of their windows, from the tops of houses, and threw tiles upon their heads. Finding one house better manned than ordinary, and many shots fired at us out of the windows, I caused my men to attack it, and resolved to make them an example for the rest; which they did. Breaking open the doors, they killed all they found there without distinction". It was reported that 120 houses had been destroyed and that 140 wagons of plunder were sent to the Royalist stronghold of Newark. [39]

Following the Parliamentarian victory over the Royalist Army at the Battle of Naseby on 14 June 1645 Leicester was recovered by Parliament on 18 June 1645.

Industrial era

Leicester, Hotel Street

The construction of the Grand Union Canal in the 1790s linked Leicester to London and Birmingham. The first railway station in Leicester opened in 1832, in the form of the Leicester and Swannington Railway which provided a supply of coal to the town from nearby collieries.[40][41] The Midland Counties Railway (running from Derby to Rugby) linked the town to the national network by 1840. A direct link to London St Pancras was established by the Midland Railway in the 1860s. These developments encouraged and accompanied a process of industrialisation which intensified throughout the reign of Queen Victoria. Factories began to appear, particularly along the canal and river, and districts such as Frog Island and Woodgate were the locations of numerous large mills. Between 1861 and 1901, Leicester's population increased from 68,100 to 211,600 and the proportion employed in trade, commerce, building, and the city's new factories and workshops rose steadily. Hosiery, textiles, and footwear became the major industrial employers: manufacturers such as N. Corah & Sons and the Cooperative Boot and Shoe Company were opening some of the largest manufacturing premises in Europe. They were joined, in the latter part of the century, by engineering firms such as Kent Street's Taylor and Hubbard (crane makers and founders), Vulcan Road's William Gimson & Company (steam boilers and founders), and Martin Street's Richards & Company (steel works and founders).

The politics of Victorian Leicester were lively and very often bitter. Years of consistent economic growth meant living standards generally increased, but Leicester was a stronghold of Radicalism. Thomas Cooper, the Chartist, kept a shop in Church Gate. There were serious Chartist riots in the town in 1842 and again six years later.[42] The Leicester Secular Society was founded in 1851 but secularist speakers such as George Holyoake were often denied the use of speaking halls. It was not until 1881 that Leicester Secular Hall was opened. The second half of the 19th century also witnessed the creation of many other institutions, including the town council, the Royal Infirmary, and the Leicester Constabulary. It also benefited from general acceptance (and the Public Health Acts ) that municipal organisations had a responsibility to provide for the town's water supply, drainage, and sanitation. In 1853, backed with a guarantee of dividends by the Corporation of Leicester the Leicester Waterworks Company built a reservoir at Thornton for the supply of water to the town. This guarantee was made possible by the Public Health Act 1847 and an amending local Act of Parliament of 1851. In 1866 another amending Act enabled the Corporation of Leicester to take shares in the company to enable another reservoir at Cropston, completed in 1870. The Corporation of Leicester was later able to buy the waterworks and build another reservoir at Swithland, completed in the 1890s.[43]

Leicester became a county borough in 1889, although it was abolished in 1974 as part of the Local Government Act, and was reformed as a non-metropolitan district and city. The city regained its unitary status, being administered separately from Leicestershire, in 1997. The borough had been expanding throughout the 19th century, but grew most notably when it annexed Belgrave, Aylestone, North Evington, Knighton, and Stoneygate in 1892.

Early 20th century

In 1900, the Great Central Railway provided another link to London, but the rapid population growth of the previous decades had already begun to slow by the time of Queen Victoria's death in 1901.

_cropped.jpg.webp)

World War I and the subsequent epidemics had further impacts. Nonetheless, Leicester was finally recognised as a legal city once more in 1919 in recognition of its contribution to the British war effort. Recruitment to the armed forces was lower in Leicester than in other English cities, partly because of the low level of unemployment and the need for many of its industries, such as clothing and footwear manufacturing, to supply the army. As the war progressed, many of Leicester's factories were given over to arms production; Leicester produced the first batch of Howitzer shells by a British company which was not making ammunition before the war. After the war, the city received a royal visit; the king and queen received a march-past in Victoria Park of thousands of serving and demobilised soldiers. Following the end of the war, a memorial arch—the Arch of Remembrance—was built in Victoria Park and unveiled in 1925. The arch, one of the largest First World War memorials in the UK, was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, who also designed the Cenotaph in London and is a grade I listed building. A set of gates and lodges, again by Lutyens, were added in the 1930s, leading to the memorial from the University Road and London Road entrances to Victoria Park.[44][45][46]

In 1927, Leicester again became a cathedral city on the consecration of St Martin's Church as the cathedral. A second major extension to the boundaries following the changes in 1892 took place in 1935, with the annexation of the remainder of Evington, Humberstone, Beaumont Leys, and part of Braunstone. A third major revision of the boundaries took place in 1966, with the net addition to the city of just over 450 acres (182 ha). The boundary has remained unchanged since that time.

Leicester's diversified economic base and lack of dependence on primary industries meant it was much better placed than many other cities to weather the tariff wars of the 1920s and Great Depression of the 1930s. The Bureau of Statistics of the newly formed League of Nations identified Leicester in 1936 as the second-richest city in Europe[47] and it became an attractive destination for refugees fleeing persecution and political turmoil in continental Europe. Firms such as Corah and Liberty Shoes used their reputation for producing high-quality products to expand their businesses. These years witnessed the growth in the city of trade unionism and particularly the co-operative movement. The Co-op became an important employer and landowner; when Leicester played host to the Jarrow March on its way to London in 1936, the Co-op provided the marchers with a change of boots. In 1938, Leicester was selected as the base for Squadron 1F, the first A.D.C.C (Air Defence Cadet Corp), the predecessor of the Air Training Corps.

World War II

Leicester was bombed on 19 November 1940. Although only three bombs hit the city, 108 people were killed in Highfields.[48]

Contemporary

The years after World War II, particularly from the 1960s onwards, brought many social and economic challenges.

Urban expansion; central rapprochement

Mass housebuilding continued across Leicester for some 30 years after 1945. Existing housing estates such as Braunstone were expanded, while several completely new estates – of both private and council tenure – were built. The last major development of this era was Beaumont Leys in the north of the city, which was developed in the 1970s as a mix of private and council housing.

There was a steady decline in Leicester's traditional manufacturing industries and, in the city centre, working factories and light industrial premises have now been almost entirely replaced. Many former factories, including some on Frog Island and at Donisthorpe Mill, have been badly damaged by fire. Rail and barge were finally eclipsed by automotive transport in the 1960s and 1970s: the Great Central and the Leicester and Swannington both closed and the northward extension of the M1 motorway linked Leicester into England's growing motorway network. With the loss of much of the city's industry during the 1970s and 1980s, some of the old industrial jobs were replaced by new jobs in the service sector, particularly in retail. The opening of the Haymarket Shopping Centre in 1971 was followed by a number of new shopping centres in the city, including St Martin's Shopping Centre in 1984 and the Shire Shopping Centre in 1992.[49] The Shires was subsequently expanded in September 2008 and rebranded as Highcross.[50] By the 1990s, as well, Leicester's central position and good transport links had established it as a distribution centre; the southwestern area of the city has also attracted new service and manufacturing businesses.

Immigration

Since World War II Leicester has experienced large scale immigration from across the world. Many Polish servicemen were prevented from returning to their homeland after the war by the communist regime,[51] and they established a small community in Leicester. Economic migrants from the Irish Republic continued to arrive throughout the post war period. Immigrants from the Indian sub-continent began to arrive in the 1960s, their numbers boosted by Asians arriving from Kenya and Uganda in the early 1970s.[52][53]

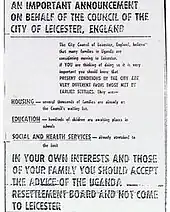

In 1972, Idi Amin announced that the entire Asian community in Uganda had 90 days to leave the country.[54] Shortly thereafter, Leicester City Council launched a campaign aimed at dissuading Ugandan Asians from migrating to the city.[55] The adverts did not have their intended effect, instead making more migrants aware of the possibility of settling in Leicester.[56] Nearly a quarter of initial Ugandan refugees (around 5000 to 6000) settled in Leicester, and by the end of the 1970s around another quarter of the initially dispersed refugees had made their way to Leicester.[57] Officially, the adverts were taken out for fear that immigrants to Leicester would place pressure on city services and at least one person who was a city councillor at the time says he believes they were placed for racist reasons.[58] The initial advertisement was widely condemned, and taken as a marker of anti-Asian sentiment throughout Britain as a whole, although the attitudes that resulted in the initial advertisement were changed significantly in subsequent decades,[59] not least because the immigrants included the owners of many of "Uganda's most successful businesses."[60]

Forty years later, Leicester's mayor Sir Peter Soulsby expressed his regret for the behaviour of the council at the time.[58]

In the 1990s, a group of Dutch citizens of Somali origin settled in the city. Since the 2004 enlargement of the European Union a significant number of East European migrants have settled in the city. While some wards in the northeast of the city are more than 70% South Asian, wards in the west and south are all over 70% white. The Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) had estimated that by 2011 Leicester would have approximately a 50% ethnic minority population, making it the first city in Britain not to have a white British majority.[61] This prediction was based on the growth of the ethnic minority populations between 1991 (Census 1991 28% ethnic minority) and 2001 (Census 2001 – 36% ethnic minority). However, Professor Ludi Simpson at the University of Manchester School of Social Sciences said in September 2007 that the CRE had "made unsubstantiated claims and ignored government statistics" and that Leicester's immigrant and minority communities disperse to other places.[62][63][61]

The Leicester Multicultural Advisory Group[64] is a forum, set up in 2001 by the editor of the Leicester Mercury, to co-ordinate community relations with members representing the council, police, schools, community and faith groups, and the media.

Coronavirus

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought many social and economic challenges across the country and across the world. Leicester has been particularly badly affected in the United Kingdom; from July 2020 during the imposition of the first local lockdown which saw all non-essential retail closed again and businesses such as public houses, restaurants and hairdressers unable to reopen. Businesses such as these in areas such as Glenfield and that part of Braunstone Town which outside of the formal city council area, have since been allowed to reopen following a more tightly defined lockdown area from 18 July 2020.[65][66]

Geography

The Office for National Statistics has defined a Leicester Urban Area (LUA); broadly the immediate Leicester conurbation, although without administrative status. The LUA contains the unitary authority area and several towns, villages and suburbs outside the city's administrative boundaries.

Areas and suburbs

Suburbs and districts of Leicester include:

- Abbey Rise

- Ashton Green

- Aylestone

- Beaumont Leys

- Bede Island

- Belgrave

- Blackfriars

- Braunstone Frith

- City Centre

- Clarendon Park

- Crown Hills

- Dane Hills

- Evington

- Evington Valley

- Eyres Monsell

- Frog Island

- Gilmorton

- Goodwood

- Hamilton

- Highfields

- Horston Hill

- Humberstone

- Humberstone Garden

- Kirby Frith

- Knighton

- Montrose

- Mowmacre Hill

- Netherhall

- Newfoundpool

- New Parks

- North Evington

- Northfields

- Rowlatts Hill

- Rowley Fields

- Rushey Mead

- Saffron

- Southfields

- South Knighton

- Spinney Hills

- Stocking Farm

- Stoneygate

- St. Matthew's

- St. Mark's

- St. Peters

- Thurnby Lodge

- West End

- West Knighton

- Western Park

- Woodgate

Climate

Leicester experiences a maritime climate with mild to warm summers and cool winters, rain spread throughout the year, and low sunshine levels. The nearest official Weather Station was Newtown Linford, about 5 miles (8.0 km) northwest of Leicester city centre and just outside the edge of the urban area. However, observations stopped there in 2003. The current nearest weather station is Market Bosworth, about 10 miles (16 km) west of the city centre.

The highest temperature recorded at Newtown Linford was 34.5 °C (94.1 °F) during August 1990,[67] although a temperature of 35.1 °C (95.2 °F) was achieved at Leicester University during August 2003.[68] However, the highest temperature since records began in Leicester is 36.7 °C (98.1 °F) on 15 July 1868.[69] More typically the highest temperature would reach 28.7 °C (83.7 °F) – the average annual maximum.[70] 11.3 days of the year should attain a temperature of 25.1 °C (77.2 °F) or above.[71]

The lowest temperature recorded at Newtown Linford was −16.1 °C (3.0 °F) during January 1963.[72] Typically, 54.9 air frosts will be recorded during the course of the year.

Rainfall averages 684.4 mm per year,[73] with 1 mm or more falling on 120.8 days.[74] All averages refer to the period 1971–2000.

| Climate data for Newtown Linford,[lower-alpha 1] elevation: 119 m (390 ft), 1971–2000 normals, extremes 1960–2002 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.6 (56.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

21.7 (71.1) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

31.5 (88.7) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.5 (94.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

16.2 (61.2) |

14.6 (58.3) |

35.0 (95.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.7 (44.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

9.3 (48.7) |

7.5 (45.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.6 (38.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

6.1 (43.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

16.1 (61.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.2 (43.2) |

4.3 (39.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.5 (32.9) |

0.5 (32.9) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.3 (37.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

2.8 (37.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

5.1 (41.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.1 (3.0) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

2.8 (37.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 61.7 (2.43) |

48.9 (1.93) |

51.9 (2.04) |

51.5 (2.03) |

50.8 (2.00) |

63.1 (2.48) |

46.1 (1.81) |

59.3 (2.33) |

61.5 (2.42) |

60.6 (2.39) |

60.3 (2.37) |

68.8 (2.71) |

684.4 (26.94) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.1 | 10.2 | 11.6 | 9.7 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 7.8 | 8.8 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 10.7 | 11.7 | 120.8 |

| Source: KNMI[lower-alpha 2][75] | |||||||||||||

Governance

On 5 May 2011, the directly elected Mayor of Leicester role came into effect after the inaugural election. This post exists in addition to that of Lord Mayor, which these days is a ceremonial post.

The first mayor of Leicester was a Norman knight, Peter fitz Roger ("Peter, son of Roger") in 1251.[76][77] Following the restoration of city status this title was elevated to "Lord Mayor." In 1987 the first Asian Mayor of Leicester was indirectly elected by the councillors, Councillor Gordhan Parmar.[78] After institution of a directly elected mayor in 2011 the Lord Mayor of Leicester still exists as a ceremonial role under Leicester City Council.[79]

On 1 April 1997, Leicester City Council became a unitary authority. Previously, local government had been a two-tier system: the city and county councils were responsible for different aspects of local-government services. That system is still in place in the rest of Leicestershire. Leicestershire County Council retained its headquarters at County Hall in Glenfield, just outside the city boundary but within the urban area. The administrative offices of Leicester City Council are in the centre of the city at City Hall in Charles Street, having moved from Welford Place. The 1970s council offices at Welford Place were declared unsafe in 2010 and demolished on 22 February 2015.[80] In 2018 a newly built New Walk Centre was completed as a privately funded mix of offices, shops and flats, alongside tree-lined open spaces.[81] Some services (particularly the police and the ambulance service) still cover the whole of the city and county, but for the most part the councils are independent.

Leicester is divided into 21 electoral wards: Abbey, Aylestone, Beaumont Leys, Belgrave, Braunstone Park & Rowley Fields, Castle, Evington, Eyres Monsell, Fosse, Humberstone & Hamilton, Knighton, North Evington, Rushey Mead, Saffron, Spinney Hills, Stoneygate, Thurncourt, Troon, Westcotes, Western, and Wycliffe.[82]

Political control

The current directly elected mayor is Sir Peter Soulsby of the Labour Party.[83][84]

After a long period of Labour administration (since 1979), the city council from May 2003 was run by a Liberal Democrat/Conservative coalition under Roger Blackmore, which collapsed in November 2004. The minority Labour group ran the city until May 2005, under Ross Willmott, when the Liberal Democrats and Conservatives formed a new coalition, again under the leadership of Roger Blackmore.

In the local government elections of 3 May 2007, Leicester's Labour Party once again took control of the council in what can be described as a landslide victory. Gaining 18 new councillors, Labour polled on the day 38 councillors, creating a governing majority of +20. Significantly however, the Green Party gained its first councillors in the Castle Ward, after losing on the drawing of lots in 2003, though one of these subsequently resigned and the seat was lost to Labour in a by-election on 10 September 2009.[85] The Conservative Party saw a decrease in their representation. The Liberal Democrat Party was the major loser, dropping from 25 councillors in 2003 to only 6 in 2007. This was in part due to the local party splitting, with a number of councillors standing for the Liberal Party.

In the local government elections of 5 May 2011 and those of May 2015, Labour won 52 of the city's 54 seats, with the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats winning one seat each.[86] In the 2019 local elections, the Labour Party gained the sole Conservative held ward of Knighton leaving Nigel Porter of the Liberal Democrats as the only opposition member on the city council.

The current composition of Leicester City Council is as follows:

| Party | Seats[87] | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour | 31 | |

| Conservative | 17 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 3 | |

| Green | 3 | |

Representation at Westminster

Leicester is divided into three Parliamentary constituencies: Leicester East, represented by Claudia Webbe, Leicester South, represented by Jon Ashworth, and Leicester West represented by Liz Kendall. Ashworth and Kendall are members of the Labour Party, while Webbe sits as an Independent MP after being expelled from the Labour Party in November 2021. In April 2011 the then Leicester South MP Sir Peter Soulsby left the House of Commons to seek election as Mayor of Leicester.

Coat of arms

The Corporation of Leicester's coat of arms was first granted to the city at the Heraldic Visitation of 1619, and is based on the arms of the first Earl of Leicester, Robert Beaumont. The charge is a cinquefoil ermine, on a red field, and this emblem is used by the city council.

After Leicester became a city again in 1919, the city council applied to add to the arms. Permission for this was granted in 1929, when the supporting lions, from the Lancastrian Earls of Leicester, were added.

The motto "Semper Eadem" was the motto of Queen Elizabeth I, who granted a royal charter to the city. It means "always the same" but with positive overtones meaning unchanging, reliable or dependable, and united. The crest on top of the arms is a white or silver legless wyvern with red and white wounds showing, on a wreath of red and white. The legless wyvern distinguishes it as a Leicester wyvern as opposed to other wyverns. The supporting lions are wearing coronets in the form of collars, with the white cinquefoil hanging from them.

Demography

Comparing

In the 2011 census, the population of the Leicester unitary authority area was 329,839, an increase of 11.8% compared to the United Kingdom Census 2001 figure of 279,921. The wider Leicester Urban Area,[88] showed an estimated population of 509,000. The population of the Leicester unitary authority area is marginally higher than that of Nottingham, while Nottingham has a higher urban area population compared to Leicester. Eurostat's Larger Urban Zone lists the population of the Leicester LUZ at 886,673 (2017) below that of Nottingham;[89] metropolitan and city region populations tend to be similar. According to the 2011 census Leicester had the largest proportion of people aged 19-and-under in the East Midlands at 27 per cent. Coventry, to the south west, has a population of 352,900 (2016 est.) compared to Leicester's 348,300 at the same date. Nonetheless, Coventry has an area one third greater than Leicester's, approximately equivalent to a combined 'Leicester + Oadby and Wigston' with a respective population of 404,100 (2016 est.).

The Eurostat regional yearbook 2015 classifies Leicester as one of country's eleven 'Greater Cities', together with Birmingham and Nottingham in the Midlands. Leicester is second only to Bristol as the largest unitary authority city in England (List of English districts by population 2015 estimates), and ninth largest counting both unitary authority cities and cities within metropolitan counties.

| Leicester compared[90] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| UK Census 2011 | Leicester | East Midlands | England |

| Total population | 329,839 | 4,533,222 | 53,012,456 |

| Foreign born | 33.6% | 9.9% | 13.8% |

| White (2001) | 63.9% | 93.5% | 90.9% |

| White (2011) | 50.6% | 89.3% | 85.5% |

| South Asian (2001) | 29.9% | 4.0% | 4.6% |

| South Asian (2011) | 31.8% | 5.1% | 5.5% |

| Black (2001) | 3.1% | 0.9% | 2.3% |

| Black (2011) | 6.3% | 1.7% | 3.4% |

| Mixed (2001) | 2.3% | 1.9% | 1.3% |

| Mixed (2011) | 3.5% | 1.4% | 2.2% |

| East Asian and Other (2001) | 0.8% | 0.5% | 0.9% |

| East Asian and Other (2011) | 5.3% | 1.3% | 2.2% |

| Christian | 32.4% | 58.8% | 59.4% |

| Muslim | 18.6% | 3.1% | 5.0% |

| No religion | 17.4% | 15.2% | 24.7% |

| Hindu | 15.2% | 2.0% | 1.5% |

| OTHERS | n% | N2% | N3% |

| English as a main language | 69.3% | 93.3% | 90.9% |

In terms of ethnic composition, according to the 2011 census, 50.6% of the population was White (45.1% White British, 0.8% White Irish, 0.1% Gypsy or Irish Traveller, 4.6% Other White), 37.1% Asian (28.3% Indian, 2.4% Pakistani, 1.1% Bangladeshi, 1.3% Chinese, 4.0% Other Asian), 3.5% of mixed race (1.4% White and Black Caribbean, 0.4% White and Black African, 1.0% White and Asian, 0.7% Other Mixed), 6.3% Black (3.8% African, 1.5% Caribbean, 1.0% Other Black), 1.0% Arab and 1.6% of other ethnic heritage.[91]

As of 2015, Leicester is the second fastest growing city in the country.[92]

Languages

A demographic profile of Leicester published by the city council in 2008 noted:

Alongside English, around 70 languages and/or dialects spoken in the city. In addition to English and the primary western and central European languages, eight ethnic languages are sometimes heard: Gujarati is the preferred language of 16% of the city's residents, Punjabi 3%, Somali 4% and Urdu 2%. Other smaller language groups include Hindi, Bengali. With continuing migration into the city, new languages and or dialects from Africa, the Middle East and Eastern Europe are also being spoken in the city. In certain primary schools in Leicester, English may not be the preferred language of 45% of pupils and the proportion of children whose first language is known, or believed to be, other than English, is significantly higher than other cities in the Midlands or the UK as a whole.[93]

Certain European languages such as Polish will undoubtedly feature in current statistics, although their prevalence may reduce subsequently as future generations rapidly assimilate or return to places of origin, given cultural and geographic proximity and changes in the geo-political environment.

Leicester is believed to be the birthplace of the modern standard English language.[94]

Population change

| Historic and projected Population growth in Leicester since 1901 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 2001 | 2011 | 2016 | 2021 | 2026 | 2031 | ||

| Population | 211,579 | 227,222 | 234,143 | 239,169 | 261,339 | 285,181 | 273,470 | 284,208 | 279,921 | 329,839 | 348,343 | 362,500 | 376,000 | 390,000 | ||

| Source: A Vision of Britain through Time[95] | ONS[96] | ONS Projections[97] | ||||||||||||||

As one of the fastest-growing cities in the country, the ONS 2014 basis population projections indicate the city will be home to 400,000 inhabitants by around 2035.

Economy

Leicester has the second largest economy in the East Midlands, after Nottingham.[98]

Companies that have their principal offices or significant sites in Leicester and the surrounding area include; Brantano Footwear, Dunelm Mill, Next, Shoe Zone, Everards brewing and associated businesses, KPMG, Mazars, Cambridge & Counties Bank, HSBC and Santander banking, Hastings Insurance, British Gas, British Telecom, Caterpillar (Inc.), Topps Tiles and DHL.[99]

Textiles

The city has historically had a strong association with the production of textiles, clothing and shoes. While important companies such as Corah, Liberty Shoes and Equity Shoes have closed, companies such as Next and Boden are still active and ASOS and New Look manufacture in the city. Moreover, in recent years the higher transport prices and longer lead-times associated with globalised production in Asia mean some textile manufacturers are locating to the city.[100][101]

There have long been concerns about the working conditions in this sector. Leicester's garment district is home to more than 1,000 factories employing as many as 10,000 workers. It has received fewer than 60 health and safety inspections and only 28 fire inspections since October 2017. HMRC has made just 36 visits checking on compliance with minimum wage legislation; it has issued penalties to fewer than 10 textile firms and claimed just over £100,000 in arrears relating to 143 workers.[102] Research at the University of Leicester in 2010 and published in 2015 found there were 11,700 employees where 75-90% were being paid £3 per hour, which was less than half of the then legal minimum wage.[103] In 2017 Peter Soulsby, Mayor of Leicester called together 40 regulatory organisations to coordinate a response. He aimed to make sure that Leicester had the highest standards of employment; that workers are properly paid, well trained and work in safe environments,[104] In 2020 the HSE was alerted to COVID-19 non-compliance.[105]

Engineering

Engineering companies include Jones & Shipman (machine tools and control systems), Richards Engineering (foundry equipment), Transmon Engineering (materials handling equipment) and Trelleborg (suspension components for rail, marine, and industrial applications). Local commitment to nurturing British engineers includes apprenticeship schemes with local companies, and academic-industrial connections with the engineering departments at Leicester University, De Montfort University, and nearby Loughborough University. Leicester was also home to the famous Gents' of Leicester clock manufacturers.

Shopping

The city centre has two large shopping malls – Highcross Leicester and the Haymarket Shopping Centre. The Haymarket Shopping Centre opened in 1974 and has two levels of shopping, multi-storey parking for up to 500 cars, a bus station and is home to the Haymarket Theatre. Highcross Leicester opened in 2008 after work to redevelop "The Shires Centre" was completed at a cost of £350 million (creating 120 stores, 15 restaurants, a cinema, 110,000 m2 of shopping space).

St Martin's Square and the Leicester Lanes area has numerous designer and specialist shops; several of the city's Victorian arcades are located in the same neighbourhood. Leicester Market is the largest outdoor covered market in Europe.[106] It central feature, the Leicester Corn Exchange, has been converted into a public house.[107]

Central Leicester is the location for several department stores including John Lewis, Debenhams.

The Golden Mile is the name given to a stretch of Belgrave Road renowned for its authentic Indian restaurants, sari shops, and jewellers; the Diwali celebrations in Leicester are focused on this area and are the largest outside the sub-continent.[108]

Food and drink

Henry Walker was a successful pork butcher who moved from Mansfield to Leicester in the 1880s to take over an established business in High Street. The first Walker's crisp production line was in the empty upper storey of Walker's Oxford Street factory in Leicester. In the early days the potatoes were sliced by hand and cooked in an ordinary deep fryer. In 1971 the Walker's crisps business was sold to Standard Brands, an American firm, who sold on the company to Frito-Lay. Walker's crisps makes 10 million bags of crisps per day at two factories in Beaumont Leys, and is the UK's largest grocery brand.[109] The Beaumont Leys manufacturing plant is world's largest crisp factory.[110]

Meanwhile, the sausage and pie business was bought out by Samworth Brothers in 1986. Production outgrew the Cobden Street site and pork pies are now manufactured at a meat processing factory and bakery in Beaumont Leys, coincidentally near to the separately owned crisp factories. Sold under the Walker's name and under UK retailers own brands such as Tesco,[111] over three million hot and cold pies are made each week.[112] Henry Walker's butcher shop at 4–6 Cheapside sold Walker's sausages and pork pies until March 2012 when owner Scottish Fife Fine Foods ceased trading, although the shop was temporarily open and selling Walker's pies for the Christmas 2012 season.[113]

Landmarks

There are ten scheduled monuments in Leicester and thirteen Grade I listed buildings: some sites, such as Leicester Castle and the Jewry Wall, appear on both lists.

20th-century architecture: Leicester University Engineering Building (James Stirling & James Gowan : Grd II Listed), Kingstone Department Store, Belgrave Gate (Raymond McGrath : Grd II Listed), National Space Centre tower.

Older architecture:

Parks: Abbey Park, Botanic Gardens, Castle Gardens, Grand Union Canal, Knighton Park, Nelson Mandela Park, River Soar, Victoria Park, Watermead Country Park.

Industry: Abbey Pumping Station, National Space Centre, Great Central Railway.

Historic buildings: Town Hall, Guildhall, Belgrave Hall, Jewry Wall, Secular Hall, Abbey, Castle, St Mary de Castro, The City Rooms, Newarke Magazine Gateway.

Shopping: Abbey Lane-grandes surfaces, Beaumont Shopping Centre, Belvoir Street/Market Street, Golden Mile, Haymarket Shopping Centre, Highcross, Leicester Lanes, Leicester Market, St Martin's Square, Silver Arcade area.

Sport: King Power Stadium – Leicester City FC, Welford Road – Leicester Tigers, Grace Road – Leicestershire County Cricket Club, Paul Chapman & Sons Arena, Leicester Lions Speedway, Leicester Sports Arena – Leicester Riders, Saffron Lane sports centre – Leicester Coritanian Athletics Club.

Transport

Air

East Midlands Airport (EMA), at Castle Donington 20 miles (32 km) north-north-west of the city, is the closest international airport. The airport is a national hub for mail/freight networks.

Leicester Airport (LRC) is a small airport, some 6 miles (9.7 km) east of Leicester city centre; it does not operate scheduled services.

Road

Leicester is at the midpoint of the primary English north/south M1 motorway between London and Leeds, served by junctions 21, 21A and 22. This is where the M1 transects with one of the primary north-east to south-west routes, the M69 motorway/A46 corridor linking to the A1 and M6 motorway at Newark-on-Trent and Coventry respectively. The M42 motorway towards Birmingham Airport terminates in north-west Leicestershire, some 12 miles (19 km) west-north-west of the Leicester urban area. Leicester is at the nexus of the A6/(A14), A50, A47 and A607 trunk roads and A426 and A5199 primary routes.

Buses

Leicester has two main bus stations: St. Margarets and Haymarket, which was recommissioned in May 2016. The main bus operators for Leicester and the surrounding area are Arriva Fox County, Centrebus, First Leicester, Hinckley Bus (Part of Arriva Midlands), Kinchbus, Leicester Bus and Stagecoach Midlands.

The Star trak real time system was introduced in 2000 by Leicester City Council; it allowed bus tracking and the retrieval of bus times by text message or online. The system was discontinued in 2011.

There are three permanent Park and Ride sites at Meynells Gorse (Leicester Forest East), Birstall and Enderby; buses operate every 15 mins from all sites. The park and ride services are branded as quicksilver shuttle and are contracted to Roberts' Coaches from the City Council and County Council; buses use a purpose-built terminal near St. Nicholas Circle.

Leicester has two circular bus services: Hop! which operates anticlockwise in the city centre via the railway station and Haymarket bus station, and the larger 30-mile (48-kilometre) long Orbital which operates in both directions.[114][115]

Cycling

National Cycle Network Route 6 passes through Leicestershire along with other secondary routes. The Leicester Bike Park is in Town Hall Square. Cycle Works Bike Mechanic Training Centre is in Wellington Street Adult Education Centre and former Central Lending Library.

Since 2021, the city has an electric bicycle sharing scheme, Santander Cycles Leicester. The scheme is a joint venture between Leicester City Council, the operator Ride On, Enzen Global as delivery partner and additional funding provided through sponsorship with Santander.[116]

Mainline rail

The rail network is of growing importance in Leicester and, with the start of Eurostar international services from London St Pancras International in November 2007, Leicester railway station has gained connections at St. Pancras station to Lille, Brussels and Paris onwards.

Inter-city services are operated by East Midlands Railway providing connectivity on 'fast' and 'semi-fast' services to London, the south-east and to major locations in the East Midlands and Yorkshire; there are also local services operating within the East Midlands region. Trans-regional services to the West Midlands and East Anglia are provided by CrossCountry, enabling connections at nearby Nuneaton, onto the West Coast main line, and at Peterborough to the East Coast Main Line.

The 99 miles (159 km) from Leicester Railway Station to London St Pancras International on the Midland Main Line are covered in an average of 1h 25m during the morning peak, with journey times as low as 1h 06m later in the day. Transfers onto London Underground or Thameslink train services to London City or West End add another 15 to 25 minutes to the journey time; double that to Canary Wharf. The journey time to Sheffield is around one hour, with Leeds and York taking approximately two. Birmingham is 50 minutes away and Cambridge, via Peterborough, can be reached in around 1 hour 55m with further direct services available onto Stansted Airport in north Essex.

Great Central Railway

The decommissioned Leicester Central railway station is on the late Victorian Great Central Railway line that ran from London Marylebone northwards. Beeching cuts closed the route in the late 1960s. A preserved section, however, remains operational in the East Midlands centred on Loughborough Central railway station providing tourist services through central Leicestershire, passing Swithland Reservoir on to the Leicester North railway station terminus.

Waterways

Two navigable waterways join at Leicester: The Leicester Line of the Grand Union Canal, and the River Soar Navigation. The Grand Union Canal links Leicester with London and Birmingham to the south, and joins the Soar in Leicester, which links the city to the River Trent, and the Trent and Mersey Canal to the north.[117]

Education

Schools

Leicester is home to a number of comprehensive schools and independent schools. There are three sixth form colleges, all of which were previously grammar schools.

The Leicester City Local Education Authority initially had a troubled history when formed in 1997 as part of the local government reorganisation – a 1999 Ofsted inspection found "few strengths and many weaknesses", although there has been considerable improvement since then.

Tudor Grange Samworth Academy an academy whose catchment area includes the Saffron and Eyres Monsell estates, was co-sponsored by the Church of England and David Samworth, chairman of Samworth Brothers pasty makers.

Under the "Building Schools for the Future" project, Leicester City Council has contracted with developers Miller Consortium for £315 million to rebuild Beaumont Leys School, Judgemeadow Community College, the City of Leicester College in Evington, and Soar Valley College in Rushey Mead, and to refurbish Fullhurst Community College in Braunstone.[118]

Leicester City Council underwent a major reorganisation of children's services in 2006, creating a new Children and Young People's Services department.

Tertiary

Leicester is home to two universities, the University of Leicester, which attained its Royal Charter in 1957 and was ranked 12th by the 2009 Complete University Guide,[119] and De Montfort University, which opened in 1969 as Leicester Polytechnic and achieved university status in 1992.

It is also home to the National Space Centre off Abbey Lane, due in part to the University of Leicester being one of the few universities in the UK to specialise in space sciences.

Religion

The Cathedral Church of Saint Martin, Leicester,[120] usually known as Leicester Cathedral,[121] is the Church of England cathedral and is the seat of the Bishop of Leicester.[122] The church was elevated to a collegiate church in 1922 and made a cathedral in 1927 following the establishment of a new Diocese of Leicester in 1926.[123][124][125]

The Church of England parish church of St Nicholas is the oldest place of worship in the city. Parts of the church certainly date from about 880 AD, and a recent architectural survey suggested possible Roman building work. The tower is Norman. By 1825 the church was in an extremely poor condition, and plans were made for its demolition. Instead, it was extensively renovated between 1875 and 1884, including the building of a new north aisle. Renovation continued into the twentieth century. A fifteenth-century octagonal font. from the redundant Church of St Michael the Greater, Stamford, was transferred to St Nicholas.[126]

St Peter's Lane takes its name from the former medieval church of that name, which closed in the 1570s, its parish having merged with All Saints church.[127]

In the 19th century Leicester was a centre for Nonconformist sects and many religious buildings were built including Baptist, Congregational, Methodist as well as Catholic congregations.[128][129][130]

In 2011 Christians were the largest religious group in the city at 32.4%, with Muslims next (18.6%), followed by Hindus (15.2%), Sikhs (4.4%), Buddhists (0.4%), and Jews (0.1%). In addition, 0.6% belonged to other religions, 22.8% identified with no religion and 5.6% did not respond to the question.[131]

The city is home to places of worship or gathering for all the faith groups mentioned and many of their respective sub-denominations. In the case of Judaism, for example, with only 0.1% declaring it as their faith, the city hosts two active synagogues: one Liberal and one Orthodox.

Places of worship

Places of worship include: Holy Cross Priory (Roman Catholic), Shree Jalaram Prarthana Mandal (Hindu temple),[132] the Stake Centre of the LDS Church's Stake, four Christadelphian meeting halls,[133] Jain Centre,[134] Leicester Cathedral, Leicester Central Mosque,[135] Masjid Umar[136] (Mosque),[137] Guru Nanak Gurdwara (Sikh), Neve Shalom Synagogue (Progressive Jewish).

Culture

The city hosts annually a Caribbean Carnival and parade (the largest in the UK outside London), Diwali celebrations (the largest outside of India),[138] the largest comedy festival in the UK Leicester Comedy Festival and a Pride Parade (Leicester Pride). Belgrave Road, not far from the city centre, is colloquially known as "The Golden Mile" because of the number of Jewellers.

The Leicester International Short Film Festival is an annual event; it commenced in 1996 under the banner title of "Seconds Out". It has become one of the most important short film festivals in the UK and usually runs in early November, with venues including the Phoenix Square.[139][140][141]

Notable arts venues in the city include:

- Curve: Purpose-designed performing arts centre, designed by Rafael Viñoly, opened in Autumn 2008,[142]

- The De Montfort Hall

- The Haymarket Theatre

- The Little Theatre

- The Y Theatre at the YMCA[143]

- The Peepul Centre, Designed by Andrzej Blonski Architects, the £15 million building was opened in 2005 and houses an auditorium, restaurant, cyber café, gym and dance studio for the local people, as well as being used for conferences and events. The centre has even been host to former Prime Minister Gordon Brown and other senior Labour Party figures for hustings during the deputy leadership contest.

- Phoenix Square, which in 2009, replaced the Phoenix Arts Centre.

- The Sue Townsend Theatre – which opened in the former Phoenix Arts Centre.

Museums

Newarke Houses Museum (Grade II*)

Newarke Houses Museum (Grade II*)

Music

In popular culture

Leicester is the setting for the fictional diaries of Adrian Mole, created by Sue Townsend. In the early books he lives in a suburb of Leicester and attends a local school where he first meets "the love of his life", Pandora Braithwaite.

After a period of years spent working in Oxford and London, Mole returns to Leicester and gets a job in a second-hand bookshop and a flat in an "upmarket" development on a swan-infested waterfront, which is a barely disguised representation of the area near to St. Nicholas Circle. Vastly in debt he is forced to move to the fictional village of Mangold Parva. The local (fictional) Member of Parliament (MP) for the town of Ashby de la Zouch is his old flame, Pandora Braithwaite.

Leicester is the setting for Rod Duncan's novels, the Fall of the Gas-Lit Empire series and the Riot trilogy.

Leicester and the surrounding county are settings for several Graham Joyce novels, including Dark Sister, The Limits of Enchantment and Some Kind of Fairy Tale.

The Clarendon Park and New Walk areas of the city, along with an unnamed Charnwood village ("vaguely based upon Cossington", according to the author) are some of the settings of the 2014 novel The Knot of Isis by Chrid McGordon.

Leicester is the setting for the British children book series, The Sleepover Club, by authors Rose Impey, Narinder Dhami, Lorna Read, Fiona Cummings, Louis Catt, Sue Mongredien, Angie Bates, Ginny Deals, Harriet Castor and Jana Novotny Hunter.

Notable feature films made in the city are The Girl with Brains in Her Feet (1997), Jadoo (2013) and Yamla Pagla Deewana 2 (2013).

Sport

Leicester Tigers have been the most successful English rugby union football club since the introduction of a league in 1987, winning it a record eleven times, five more than either Bath or Wasps. They won the Premiership title most recently in 2022.[144]

Leicester City, based at the King Power Stadium, are a professional association football club who compete in the EFL Championship. Leicester attracted global attention after winning the Premier League title in 2016, despite odds at the start of the season being 5000/1.[145][146][147]

Leicester Riders are the oldest professional basketball team in the country. In 2016, they moved into the new Charter Street Leicester Community Sports Arena.[148]

Leicestershire County Cricket Club who are a professional cricket club based at Grace Road, Leicester, currently play in the second tier of the county championship. They won the County Championship in 1996 and 1998.[149]

Greyhound racing took place at two venues in the city; the main venue was the Leicester Stadium which hosted racing from 1928 to 1984, it also hosted speedway.[150] A smaller track existed at Aylestone Road (1927–1929).[151][152]

Public services

In the public sector, University Hospitals Leicester NHS Trust is one of the larger employers in the city, with over 12,000 employees working for the Trust. Leicester City Primary Care Trust employs over 1,000 full and part-time staff providing healthcare services in the city. Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust[153] employs 3,000 staff providing mental health and learning disability services in the city and county.

In the private sector are Nuffield Hospital Leicester and the Spire Hospital Leicester.

Notable people

Local media

Print and online

The Leicester Mercury was founded by James Thompson in 1874. Until recently, it was based at 16–18 New Walk but since the COVID-19 pandemic it operates almost entirely remote. The newspaper is currently owned by Reach plc.

Pukaar Group, a local media company, publishes the Leicester Times.

A co-operative and independent newspaper, the Great Central Gazette, was launched online in March 2023. It is based on the model pioneered by The Bristol Cable. It plans to launch a print edition in 2024.[154]

National World has plans to launch online-only Leicester World.[155]

Television

The Midlands Asian Television channel known as MATV Channel 6 was broadcast in Leicester until late 2009.

Radio

BBC Radio Leicester was the first BBC Local Radio station in Britain, opening on 8 November 1967. Other analogue FM radio stations are Leicester Community Radio for English speaking over 35's (1449 AM/MW), Demon FM which is Leicester's community and student radio station broadcasting from De Montfort University, Takeover Radio is the first ever children's radio station in the UK to be produced and presented by children, Capital Midlands, Gem, Smooth East Midlands and Hindu Sanskar Radio, which only broadcasts during Hindu religious festivals. BBC Asian Network and Sabras Radio broadcast on AM.

The local DAB multiplex includes Capital Midlands, BBC Radio Leicester, Gem and Smooth East Midlands.

Leicester's independent radio stations launched a new DAB multiplex in 2023.[156][157]

There are two hospital radio stations in Leicester, Radio Fox and Radio Gwendolen. Leicester University has a radio station, Galaxy Radio.

Twin cities

Leicester is twinned with six cities.[158]

|

Since 1973, the fire services of Leicester and twin city Krefeld have played each other in an annual 'friendly' football match.[161]

Freedom of the City

The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the City of Leicester.

Individuals

- Thomas Wright: 25 October 1892.

- Edward Wood: 25 October 1892.

- Thomas Windley : 31 March 1903.

- Colonel John Edward Sarson: 31 March 1903.

- Alexander Bains: 29 November 1904.

- William Wilkins Vincent: 28 November 1911.

- Thomas Smith: 3 July 1918.

- Jonathan North : 28 January 1919.

- Admiral of the Fleet Lord Beatty: 28 January 1919.

- Thomas Fielding Johnson : 8 July 1919.

- Field Marshal Lord Haig : 28 February 1922.

- Charles John Bond: 28 April 1925.

- Captain Robert Gee: 28 April 1925.

- James Ramsay MacDonald: 29 October 1929.

- Lord Laig of Lambeth: 28 May 1935.

- Walter Ernest Wilford: 26 July 1949.

- Thomas Rowland Hill: 3 January 1956.

- Lieutenant Colonel Sir Robert Martin: 3 January 1961.

- Sir Charles Robert Keene: 31 July 1962.

- Lord Janner of the City of Leicester: 26 October 1971.

- Sir Frederick Ernest Oliver: 26 October 1971.

- Sidney William Bridges: 26 October 1971.

- Mac Goldsmith: 26 October 1971.[162]

- Sir David Attenborough: 30 November 1989.

- Lord Attenborough of Kingston upon Thames: 30 November 1989.

- Professor Sir Alec Jeffreys: 26 November 1992.

- Gary Lineker: 26 November 1992.

- Frank Ephraim May: 12 July 2001.

- Rosemary Conley: 12 July 2001.

- Engelbert Humperdinck: 25 February 2009.

- Susan Lillian Townsend: 25 February 2009.

- Alan Birchenall: 25 February 2009.

Military units

- The Royal Anglian Regiment: 25 January 1996.[163]

- The 9th/12th Royal Lancers: 30 June 2011.[164]

Notes

- Weather station is located 5 miles (8 km) from the Leicester city centre.

- Data calculated from raw monthly term data

References

- 2021 census

- Leicester Urban Area 2011

- Eurostat's Leicester 'Functional Urban Area' 2011: <> (Central) Metropolitan area

- "Leicester Archived 19 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine", Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 28 August 2015

- "How the population changed in Leicester, Census 2021 - ONS". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- "UNITED KINGDOM: Urban Areas in England". City Population. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- "The National forest". The National forest. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names Based on the Collections of the English Place-Name Society, ed. by Victor Watts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), s.v. LEICESTER, LEIRE.

- Stevenson, W. H. (1918). "A note on the derivation of the name 'Leicester'". The Archaeological Journal. Royal Archaeological Institute (London). 75: 30 f. Dudley, John (1848). "Etymology of the Name of Leicester". The Gentleman's Magazine. Vol. 184. pp. 580–582. citing Wilford, Asiatick Researches vol. ii. No. 2 (1812), p. 45: "The learned Somner says that the river which runs by it [Leicester] was formerly called Leir by the same contraction [from Legora], and it is probably the river Liar of the anonymous geographer. Mr. Somner, if I be not mistaken, places the original own of Ligora near the source of the Lear, now the Soar".

- Gelling et al. (eds.), The names of towns and cities in Britain, B. T. Batsford, 1970, p. 122.

- Thompson (1849), Appendix B: Leograceaster—The Saxon Name of Leicester, pp. 448 f. Archived 19 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine; Thompson (1849), pp. 7 f Archived 17 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- Andrew Breeze, 'Historia Brittonum' and Britain’s Twenty-Eight Cities Archived 28 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine', Journal of Literary Onomastics, 5.1 (2016), 1–16 (p. 9).

- Geoffrey, Vol. II, Ch. 11.

- W. G. Hoskins, "Leicester" History Today (Sep 1951) 1#9 pp 48–56.

- "Archaeology Data Service". Archaeologydataservice.ac.uk. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- Thompson (1849), Appendix A: Ratæ—Roman Leicester, pp. 443 ff Archived 19 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- Tomlin, R S O (1983). "Roman Leicester, a Corrigendum: For Coritani should we read Corieltauvi?". Transactions of the Leicester Archaeological and Historical Society. 48.

- Tomlin, R S O (1983). "Non Coritani sed Corieltauvi". The Antiquaries Journal. 63 (2): 353–355. doi:10.1017/s0003581500066579. S2CID 161713854.

- "Richard III team makes second Leicester car park find". BBC News Leicester. 4 May 2013. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (in Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

- Ford, David Nash. "The 28 Cities of Britain Archived 15 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine" at Britannia. 2000.

- Mills, A.D. (1991). A Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 208. ISBN 0-19-869156-4.

- Galfridus Monemutensis [Geoffrey of Monmouth]. Historia Regum Britanniæ. c. 1136. (in Latin) J.A. Giles & al. (trans.) as History of the Kings of Britain, Vol. II, Ch. 11 in Six Old English Chronicles. 1842. Hosted at Wikisource.

- Geoffrey of Monmouth. Lewis Thorpe (trans.) as The History of the Kings of Britain, pp. 81 & 86. Harmondsworth, 1966. William Shakespeare took the name of his King Lear from Geoffrey; there is now a statue of the final scene of Shakespeare's Lear in Watermead Country Park.Paul A. Biggs, Sandra Biggs, Leicestershire & Rutland Walks with Children, Sigma Leisure, 2002, p. 44.

- Mundill (2002), p265

- Maddicott 1996, p.15

- Levy, S (1902), p38-39

- See Levy, S (1902), p39

- See Mundill (2002)

- Charles James Billson, Mediaeval Leicester (Leicester, 1920)

- e.g., Williamson, David (1998). The National Portrait Gallery History of the Kings and Queens of England. National Portrait Gallery Publications. p. 81. ISBN 9781855142282.

- "Richard III dig: Have they found their man in Leicester?". BBC News. 12 September 2012. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Lawless, Jill (4 February 2013). "Richard III team confirms skeleton found under parking lot is remains of England's king". The Star. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2017.j

- "Official Website of the British Monarchy – Jane". Archived from the original on 1 May 2015.

- Walter Seton, 'Early Years of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, and Charles, Duke of Albany', Scottish Historical Review, 13:52 (July 1916), pp. 373-4.

- Buchanan Sharp (1980), In contempt of all authority, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-03681-6, OL 4742314M, 0520036816p70-71

- Sharp, p58-59

- Sharp, p88

- "1645:The Storming of Leicester and the Battle of Naseby". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- Butt 1995, p. 141.

- Elliott, Malcolm (1979). Victorian Leicester. London and Chichester: Phillimore. p. 26. ISBN 0-85033-327-X.

- "Chartism in Leicestershire". A Web of English History. Dr Marjie Bloy. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- Elliott, Malcolm.op cit pages 62 -64 and 124–135

- Richardson, p. 63.

- Beazley, pp. 174–175.

- Historic England. "The Arch of Remembrance (1074786)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- William, David (13 October 2010). UK Cities: A Look at Life and Major Cities in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. New Africa Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-9987160211.

- "The Blitz in Highfields". Story of Leicester. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- "A History of Leicester". Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Highcross - Highcross". Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- "Poles". Encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Leicester's Ugandan Asian success story. Archived 1 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- A history of Leicester. Archived 8 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- "From Kampala to Leicester". Leicester City Council. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- Lowther, Ed (30 January 2013). "Government warned not to repeat 'folly' of Uganda anti-immigration adverts". BBC. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- "Leicester City Council to thank Indian immigrants". Immigration Matters. 10 September 2012. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- Huttman, Elizabeth D. (1991). Blauw, Wim; Juliet Saltman (eds.). Urban housing segregation of minorities in Western Europe and the United States. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822310600.

- "Ugandan Asians advert 'foolish', says Leicester councillor". BBC News. 8 August 2012. Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- Marett, Valerie (1989). Immigrants settling in the city. Leicester: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0718512835.

- "Scoring goals for integration in Leicester: CRE helps kids and coaches use football to bring communities together". 30 September 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- "Research2". Archived from the original on 29 November 2007.

- "Media4diversity". Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- "Leicester lockdown: 'I needn't have cancelled our holiday'". BBC News. 18 July 2020.

- "The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (Leicester) (Amendment) Regulations 2020". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- "August 1990 Maximum". Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- "August 2003 Maximum". Archived from the original on 19 August 2003. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- "Leicestershire experiences hottest July day in more than 150 years - Leicestershire Live". Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "1971-00 Average annual maximum". Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- "Max > 25 °C days". Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- "Jan 1963 Minimum". Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- "1971-00 average rainfall". Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- "1971-00 average raindays". Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- "Indices Data - Newtown Linford Station 1852". KNMI. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- Agnes Johnson Glimpses of ancient Leicester – Page 60 1891 "The first Mayor of Leicester, A.D. 1251.

- The history of the boroughs and municipal corporations of the ... – Page 229 Henry Alworth Merewether, Archibald John Stephens – 1835 "The mayor of Leicester and his brethren, having, with the consent of the commonalty, by the last ordinance, placed the town under the government of the aldermen, appear, in the 4th year of the reign of King Henry VII., to have adopted 1488. a ..."

- What participation by foreign residents in public life at local ... – Page 91 Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of Europe – 2000 "In 1981 serious riots broke out in the city that were dubbed "race riots" in Highfields and the City centre. ... In 1987 the first Asian Mayor of Leicester was elected, Councillor Gordhan Parmar and the first Asian Member of Parliament (MP), Keith Vaz

- "Leicester's elected mayor reports lord mayor over parking". BBC. August 2011. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Hartley-Parkinson, Richard (22 February 2015). "City's skyline changed as council offices are pulled down". Metro.

- "Redevelopment of the former Leicester City Council site, New Walk, Leicester". Procon-leicestershire.co.uk. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- "Leicester City Mayor and Councillors Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine", Leicester City Council, July 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017

- "BBC". 6 May 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- "Sir Peter Soulsby". Leicester City Council. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Leicester City Council - Elections". Archived from the original on 4 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- "Elections and voting". Archived from the original on 9 May 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- "Leicester City Council". BBC News. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "2011 Census – Built-up areas". ONS. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- "Population on 1 January by age groups and sex – functional urban areas". Eurostat – Data Explorer. Eurostat. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2019.