Midland Counties Railway

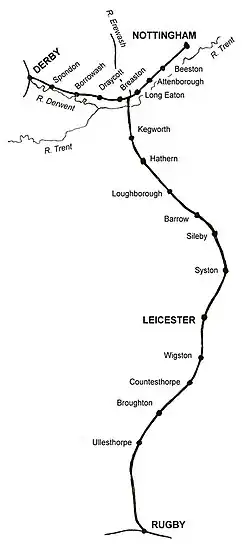

The Midland Counties' Railway (MCR) was a railway company in the United Kingdom which existed between 1839 and 1844, connecting Nottingham, Leicester and Derby with Rugby and thence, via the London and Birmingham Railway, to London. The MCR system connected with the North Midland Railway and the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway in Derby at what become known as the Tri Junct Station. The three later merged to become the Midland Railway.

Map of the route of the Midland Counties' Railway | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Derby |

| Reporting mark | MCR |

| Dates of operation | 1839–1844 |

| Successor | Midland Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

Midland Counties Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The part of the MCR line between Nottingham, Derby and Leicester is still in use as part of the Midland Main Line, the part of the route from Leicester to Rugby however was closed in the 1960s.

Origin

The East Midlands had for some years been at centre of plans to link the major cities throughout the country. However, the MCR came about as a result of competition to supply coal to Leicester, a town which was rapidly industrialising and was a valuable market for coal. The competition was between the Coalville area of Leicestershire, and the Erewash Valley area of Nottinghamshire.

For many years, the Nottinghamshire coal miners had enjoyed a competitive advantage over their counterparts in Leicestershire, but in 1832 the latter opened the Leicester and Swannington Railway.

On 16 August 1832, at one of the Nottinghamshire miner's regular meetings at the Sun Inn, at Eastwood the idea was mooted to extend the Mansfield and Pinxton Railway to Leicester.[1]: 86 The decision was taken to involve outside finance, and, on 27 August 1832, a public meeting to attract subscriptions was held at the George Inn at Alfreton and on 26 September 1832 the scheme was formally approved at Eastwood,[2] though at that time the possibility of using steam locomotives had not been discussed. In the Derby Mercury of 17 October 1832, the new railway was referred to as the Midland Counties' Railway.[3]

Josias Jessop was retained as engineer, and reporting in 1833, noted that it would not be possible to put it before Parliament that year. Subscriptions had been obtained from Lancashire investors and with the imminent completion of the London and Birmingham Railway, they insisted that the line should continue to join it at Rugby, Warwickshire. George Rennie was brought in to assess the scheme and plan the southward extension.

Not surprisingly there had been opposition from Leicestershire to the proposal. In October an alternative plan was proposed of bringing in Nottingham and Derby, as well as Leicester, using a junction at Long Eaton, with the stated aim that it would reduce any differences in coal prices between them.

At last the plans were ready to put before Parliament in its 1834 session. However investment fell far short of the expected cost of over £125,000 (equivalent to £12,780,000 in 2021).[4] The scheme was delayed for yet another year, during which time Charles Vignoles was asked to review the plans and become the company's engineer.[1]: 89

At this point, the citizens of Northampton campaigned for the line to pass through their town rather than Rugby. Not surprisingly, at that late stage, it was refused. It has been suggested that, having opposed the London and Birmingham, they had seen the error of their ways. Such a line would have been longer and more expensive, shortening the journey to London by very little, but extending that to Birmingham excessively.

By that time, the North Midland Railway and Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway had been formed with the intention of meeting at Derby. The line to Pinxton threatened it, particularly as, in 1834, the Midland Counties had mooted the possibility of an extension to Clay Cross.

At the same time, the Birmingham and Derby link with the London and Birmingham Railway in a southwards direction at Hampton-in-Arden, threatened the Midland Counties. The two railways came to a private agreement to withdraw the competing lines from their Bills.

At last in 1836 the Midland Counties' Railway Bill went before Parliament and survived its passage through the House of Commons.[1]: 89 However, there were still powerful interests ranged against it. Firstly there were the canal owners with which it was being built to compete. Secondly, the Bill still included the Pinxton line, to the extreme annoyance of the Birmingham and Derby line's directors. There was a distinct possibility that the Lords would insist that the North Midland was connected to it instead of proceeding to Derby, losing the NMR some twenty miles of line and its connection to Birmingham and the West Country. Accordingly, it was dropped.

The Bill received Royal Assent on 21 June 1836 without the connection to Pinxton.[5] Since this was the original reason for building the railway, one can imagine the feelings of the Nottinghamshire miners.

Construction

Nottingham to Derby

In January 1837[6] the company issued invitations to tender for three contracts, Derby to Trent Junction, Nottingham to Trent Junction and Trent Junction to Sutton Bonington. By February 1837, the engineers had marked out the whole of the line.[7] The principal contractors struggled to meet the deadline of 22 February to quote for the construction of 22 miles of railway, so the deadline was extended to 28 February, with the additional requirement of a cast-iron bridge over the River Trent at Thrumpton.[8]

Contracts were awarded for the Derby to Trent Junction portion by April 1837 for £3,000 (equivalent to £290,000 in 2021)[4] under the estimate with an forecast of completion by September 1838.[9] The contract for the section from Trent Junction to Sutton Bonington was let in May 1837. The contract for the works in Nottingham were signed in June 1837 and construction started immediately. By September 1837 it was reported that 400 men were employed in three different places on the line between Nottingham and Derby.[10]

The engineer was Charles Blacker Vignoles, and the superintendent was Thomas Jackson Woodhouse.[11] The contractor for the works between Derby, Long Eaton and Loughborough was William MacKenzie of Chorley, Lancashire. The contractor for Long Eaton to Nottingham was Messrs. Taylor, Sharpe and Johnson.

The only obstacle was the Derby Canal which would need to be diverted at Borrowash, the canal owners asking £2 for every hour that it was closed. However quick action allowed the work to be completed, when a drought fortuitously occurred, closing the canal.

Initially the railway ran into a temporary platform at Derby, but at Nottingham a magnificent terminus had been built in Carrington Street.[12] The inaugural run took place from Nottingham on 30 May 1839,[13] with a timetabled public service beginning on 4 June.[14]

To Leicester and Rugby

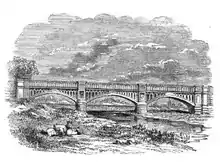

The portion of the contract from Leicester to the Trent Viaduct was let in December 1837 at which point it was reported that 900 men were engaged in the construction.[15] The contractor for Loughborough to Syston was Messrs. Gordon and Hector McLeod, and the contractor for the Syston to Leicester, and Leicester to Rugby portions was Messrs David Macintosh. It had three main obstacles, the first being the crossing of the Trent. This was done by means of an elegant three arched bridge built by the Butterley Company. Immediately following this was Redhill Tunnel, provided with elegant castellated portals to placate the local landowner. The bridge was replaced with the present girder bridge in 1900 when the line was quadrupled, and a second bore was provided for the tunnel with identical portals. Finally a substantial cutting was needed at Sutton Bonington.

While the Derby-Nottingham tracks had been supported on stone blocks, the section to Rugby used kyanised timber sleepers. At Leicester there was another magnificent station in Campbell Street, originally planned as a terminus on a spur from the main line. However, it was built as a loop with a single long platform next to the through running lines. It was replaced by the present London Road station in 1892.[1]: 91

Progress to Rugby was hampered by wet weather and the need for several long cuttings and embankments. There were two tunnels, at Knighton and near Ullesthorpe and a bridge over the River Avon and the Oxford Canal at Rugby. This last was not completed in time for the opening and, for seven weeks, passengers had to alight at a temporary platform, to be taken by road into Rugby.

Engineering

There were 148 bridges in all, and three tunnels. The rails were double headed in 15-foot (4.57 m) lengths at 77 pounds per yard (38.2 kg/m) at a gauge throughout of 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge. These were laid either on gritstone blocks from Cromford, laid diagonally, or on embankments, timber sleepers of oak or kyanised larch. For a length near Rugby, Evans's dovetailed bridge rails of 57 pounds per yard (28.3 kg/m), were tried, mounted on longitudinal Memel fir timbers with pine cross sleepers.

The earthworks ensured that the maximum gradient of the line was 1 in 330 (0.3 %). The largest were on the Rugby line at the Leire cutting and embankment. The whole project required approximately 5,700,000 cubic yards (4,400,000 m3) of earthworks.[11] There were only two significant bridges and viaducts, one being that over the River Trent, which comprised three cast iron arches of 100 feet (30.5 m) each and the viaduct over the valley of the Avon (now Grade II listed[16]) which consisted of 11 arches of 50 feet (15.24 m) each, elevating the line 40 feet (12.2 m) above the valley floor.[11]

The total cost of construction was just under £1,400,000[11] (equivalent to £134,480,000 in 2021).[4]

Opening

The line was finally opened in three stages:[1]: 90

- Derby to Nottingham 4 June 1839[17]

- Trent Junction to Leicester 4 May 1840[18]

- Leicester to Rugby 1 July 1840[19]

On 4 June 1839 the company provided four trains at Nottingham for passenger services on opening day. The first two with six coaches, and the others with two coaches each. Each train was headed by a separate engine, Ariel, Mersey, Hawk and Sunbeam. The brass band of the 5th Dragoon Guards entertained the passengers, and played God Save the Queen as each train departed. The first train headed by Sunbeam with four first class and two second class carriages departed for Derby at 12:30 pm. Five minutes later Ariel was attached to a train and departed for Derby. Ariel arrived at Long Eaton at 12:48 pm, and Derby by 1:19 pm. After a wait in Derby of just over an hour, the trains returned to Nottingham, where the band of the Dragoons struck up See, the Conqu'ring Hero Comes.[13]

One notable event was the first large organised excursion by rail, "got up by the Nottingham Mechanics' Institute. A week later the Leicester Mechanics' Institute returned the compliment to Nottingham." After Thomas Cook began the tourist business, the MCR began organising excursions on its own account, on one occasion conveying some 2,400 people in a single train of 65 four-wheeled carriages and wagons. The fact that MCR's locomotives were all either single driving-wheeled or 0-4-0s, and small at that meant that the heavier the train, the more were added. The excursion must have been a sight to behold.

Competition

Initially the Midland Counties' Railway did not prosper due to competition from the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway which also transported coal from the East Midlands to London, via Hampton-in-Arden. An ensuing price war between the two companies almost drove both of them out of business.

The MCR made an agreement with the North Midland for exclusive access to its passengers. In retaliation the Birmingham board opposed a bill that the MCR had submitted to Parliament. Both lines were in dire straits and paying minuscule dividends.

The North Midland was also suffering severe financial problems arising from the original cost of the line and its buildings. At length George Hudson took control of the NMR and adopted Robert Stephenson's suggestion that the best outcome would be for the three lines to merge.

Hudson foresaw that the directors of the MCR would resist the idea and made a secret agreement with the B&DJR for the NMR to take it over. This would of course take away the MCR's customers from Derby and the North and, when news leaked out, shares in the B&DJR rose dramatically.

Hudson was able to give the MCR directors an ultimatum, and persuaded the line's shareholders to override their board and the stage was set for amalgamation.

Midland Railway

In 1844, the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway, the Midland Counties' Railway and the North Midland Railway merged to form the new Midland Railway.[20]

The Mansfield and Pinxton Railway was finally connected in 1847, and the extension to Chesterfield was built in 1862. Now known as the Erewash Valley Line, it joined near where the three original lines met at Trent Junction, crossing to the up (London) line on the level at Platt's Crossing. This potentially dangerous arrangement was removed when Trent station was built in 1862 and the whole junction was remodelled.

This underwent many changes over the years, the station finally closing in 1968.

Legacy

Most of the original Midland Counties' Railway line between Nottingham, Derby and Leicester is still operating today as part of the Midland Main Line. The original line into Derby, through what later became the site of Chaddesden Sidings, closed in 1969. Also part of the original route was abandoned when track alterations were put in with the opening of Trent Station in the 1860s. The stretch between Leicester and Rugby was closed in 1961. The line between Trent Junction and Chesterfield, known locally as the Erewash Valley Line, is still today the second most busy in the East Midlands, with freight to the south east of the country. The daily southbound Master Cutler travels along it directly from Sheffield to London, while a few expresses divert at Trowell just north of Trent, to call at Nottingham, before travelling to London. Although the old North Midlands through Derby is the main express line (since trains have to reverse at Nottingham), there is still a half-hourly service from Nottingham itself to London.

In January 2019, Campaign for Better Transport released a report identifying the line between Rugby and Leicester which was listed as Priority 2 for reopening. Priority 2 is for those lines which require further development or a change in circumstances (such as housing developments).[21]

See also

References

- Leleux, Robin (1976). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain. Volume 9 The East Midlands. David & Charles. Newton Abbot. ISBN 0715371657.

- "Sun Inn, Eastwood". Derby Mercury. England. 26 September 1832. Retrieved 20 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Midland Counties Railway". Derby Mercury. England. 17 October 1832. Retrieved 21 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Midland Counties' Railway". Nottingham Review. England. 24 June 1836. Retrieved 20 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Midland Counties Railway. Contract for Works". Derbyshire Courier. England. 28 January 1837. Retrieved 21 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Midland Counties' Railway". Nottingham Review. England. 17 February 1837. Retrieved 20 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Midland Counties Railway". Leicester Chronicle. England. 25 February 1837. Retrieved 21 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Midland Counties Railway". Sheffield Independent. England. 22 April 1837. Retrieved 21 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Midland Counties Railway". Leicester Chronicle. England. 23 September 1837. Retrieved 21 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Tebutt's Railway Companion". Leicestershire Mercury. England. 23 May 1840. Retrieved 20 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Billson, P. (1996). Derby and the Midland Railway. Derby: Breedon Books.

- "Midland Counties Railway". Derby Mercury. England. 5 June 1839. Retrieved 20 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Butt, R.V.J., (1995) The Directory of Railway Stations, Yeovil: Patrick Stephens

- "Midland Counties Railway". Leicestershire Mercury. England. 23 December 1837. Retrieved 21 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Historic England, "Railway Viaduct (1380144)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 7 November 2017

- "Opening of the Midland Counties' Railway". Staffordshire Advertiser. England. 8 June 1839. Retrieved 20 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Midland Counties' Railway". Leicester Chronicle. England. 9 May 1840. Retrieved 20 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Midland Counties' Railway". Yorkshire Gazette. England. 4 July 1840. Retrieved 20 October 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Barnes, E. G. (1969). The Rise of the Midland Railway 1844–1874. Augustus M. Kelley, New York. p. 308.

- p.42

Sources

- The Derby Railway History Research Group (1989) The Midland Counties Railway, Railway & Canal Historical Society, ISBN 0-901461-11-3

- Anon. (1979 [1839]) The Nottingham and Derby Railway Companion, Radford, J.B. (intro.), Occasional paper : Derbyshire Record Society, 3, [first publ.: Nottingham : R.Allen], ISBN 0-9505940-4-0

- Anon. (1989) The Midland Counties Railway : 1839-1989 a pictorial survey, Midland Railway Trust, ISBN 1-872194-00-1

- Billson, P. (1996) Derby and the Midland Railway, Derby : Breedon Books, ISBN 1-85983-021-8

- Ellis, C. Hamilton (1953) The Midland Railway, London : Ian Allan, 192 p.

- Williams, R. (1988) The Midland Railway : a new history, Newton Abbot : David and Charles, ISBN 0-7153-8750-2

- Whishaw, F. (1969 [1842]) Whishaw's railways of Great Britain and Ireland, (1842) [The railways of Great Britain and Ireland], 2nd ed. reprint with a new introduction by C.R. Clinker, Newton Abbot: David and Charles, ISBN 0-7153-4786-1

Further reading

- Whishaw, Francis (1842). The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland Practically Described and Illustrated (2nd ed.). London: John Weale. pp. 324–334. OCLC 833076248.

- Williams, Frederick Smeeton (1876) The Midland railway: its rise and progress