Fitzroya

Fitzroya is a monotypic genus in the cypress family. The single living species, Fitzroya cupressoides, is a tall, long-lived conifer native to the Andes mountains and coastal regions of southern Chile, and only to the Argentine Andes, where it is an important member of the Valdivian temperate forests. Common names include alerce ("larch" in Spanish), lahuán (Spanish, from the Mapuche name lawal), and Patagonian cypress. The genus was named in honour of Robert FitzRoy.

| Fitzroya | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Gymnosperms |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Cupressales |

| Family: | Cupressaceae |

| Subfamily: | Callitroideae |

| Genus: | Fitzroya Hook. f. ex Lindl. |

| Species: | F. cupressoides |

| Binomial name | |

| Fitzroya cupressoides | |

| |

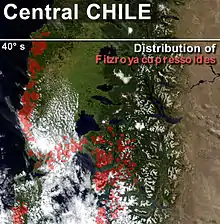

| Distribution of F. cupressoides in South-Central Chile (red) | |

Description

Fitzroya cupressoides is the largest tree species in South America, normally growing to 40–60 m, but occasionally more than 70 m, and up to 5 m in trunk diameter. Its rough pyramidal canopy provides cover for the southern beech, laurel and myrtle. The largest known living specimen is Alerce Milenario in Alerce Costero National Park, Chile. It is more than 60 m tall, with a trunk diameter of 4.26 m. Much larger specimens existed before the species was heavily logged in the 19th and 20th centuries; Charles Darwin reported finding a specimen 12.6 m in diameter.

The leaves are in decussate whorls of three, 3–6 mm long (to 8 mm long on seedlings) and 2 mm broad, marked with two white stomatal lines. This is a dioecious species, with male and female cones on separate trees.[3] The cones are globose, 6–8 mm in diameter, opening flat to 12 mm across, with nine scales in three whorls of three. Only the central whorl of scales is fertile, bearing 2–3 seeds on each scale; the lower and upper whorls are small and sterile. The seeds are 2–3 mm long and flat, with a wing along each side. The seeds mature 6–8 months after pollination.

The thick bark of F. cupressoides may be an adaptation to wildfire.[4]

In 1993 a specimen from Chile, "Gran Abuelo" or "Alerce Milenario", was found to be 3622 years old, making it the second oldest fully verified (by counting growth rings) age for any living tree species, after the bristlecone pine.[5] More recent research proposed that this individual corresponds to the oldest tree in the world.[6]

A team of researchers from the University of Tasmania found fossilized foliage of a Fitzroya species on the Lea River of northwest Tasmania.[7] The 35-million-year-old (Oligocene) fossil was named F. tasmanensis. The finding demonstrates the ancient floristic affinities between Australasia and southern South America, which botanists identify as the Antarctic flora.

About 40 to 50 thousand years ago, during the interstadials of the Llanquihue glaciation, Fitzroya and other conifers had a much larger and continuous geographical extent than at present including the eastern lowlands of Chiloé Island and the area west of Llanquihue Lake. At present Fitzroya grow mainly at some altitude above sea level. Fitzroya stands near sea level are most likely relicts.[8]

A large tree showing the bark peeling in longitudinal strips.

A large tree showing the bark peeling in longitudinal strips. A branchlet with adult leaves.

A branchlet with adult leaves. A first-year seedling with juvenile leaves.

A first-year seedling with juvenile leaves. Mature seed cones with open scales.

Mature seed cones with open scales.

History

Fitzroya cupressoides wood has been found in the site of Monte Verde, implying that it has been used since at least 13,000 years before present. The Huilliche people are known to have used the wood for making tools and weapons.[9]

By the time of the Spanish conquest of Chiloé Archipelago in 1567 most of the islands were covered by dense forest where F. cupressoides grew.[10] The wood was economically important in colonial Chiloé and Valdivia, which exported planks to Peru.[11] A single tree could yield 600 planks with a width of at least 0.5 m and a length of 5 m.[10] The wood was highly valued in Chile and Peru for its elasticity and lightness.[9] With the destruction of Valdivia in 1599 Chiloé gained increased importance as the only locale that could supply the Viceroyalty of Peru with F. cupressoides wood, the first large shipment of which left Chiloé in 1641.[10]

Fitzroya cupressoides wood was the principal means of exchange in the trade with Peru, and even came to be used as a local currency, the real de alerce, in Chiloé Archipelago.[9] It has been argued that the Spanish exclave of Chiloé prevailed over other Spanish settlements in Southern Chile due to the importance of alerce trade.[9][12]

From about 1750 to 1943, when the land between Maullín River and Valdivia was colonized by Spain and then Chile, numerous fires of Fitzroya woods occurred in Cordillera Pelada. These fires were initiated by Spaniards, Chileans and Europeans. Earlier, from 1397 to 1750 the Fitzroya woods of Cordillera Pelada also suffered from fires that originated from lightning strikes and indigenous inhabitants.[13]

In the 1850s and 1860s Vicente Pérez Rosales burned down huge tracts of forested lands to provide cleared lands for German settlers in Southern Chile.[14] The area affected by the fires of Pérez Rosales spanned a strip in the Andean foothills from Bueno River to Reloncaví Sound.[14] One of the most famous intentional fires was the one of the Fitzroya forests between Puerto Varas and Puerto Montt in 1863.[15] This burning was done taking advantage of a drought in 1863.[15] Burnings of forest were in many cases necessary for the survival of the settlers who had no means of subsistence other than agriculture.[15]

Logging of Fitzroya continued until 1976[16] when it became forbidden by law, (with the exception of already dead trees and with the authorization of CONAF, a National Corporation) although illegal logging still occasionally occurs.

See also

References

- Premoli, A.; Quiroga, P.; Souto, C.; Gardner, M. (2013). "Fitzroya cupressoides". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T30926A2798574. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T30926A2798574.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- Gymnosperm Database – Fitzroya cupressoides

- Veblen, Thomas T.; Kitzberger, Thomas; Burns, Bruce R.; Rebertus, Alan J. (1995). "Perturbaciones y dinámica de regeneración en bosques andinos del sur de Chile y Argentina" [Natural disturbance and regeneration dynamics in Andean forests of southern Chile and Argentina]. In Armesto, Juan J.; Villagrán, Carolina; Arroyo, Mary Kalin (eds.). Ecología de los bosques nativos de Chile (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Editorial Universitaria. pp. 169–198. ISBN 9561112841.

- Lara, A; Villalba, R (1993). "A 3620-Year Temperature Record from Fitzroya cupressoides Tree Rings in Southern South America". Science. 260 (5111): 1104–6. Bibcode:1993Sci...260.1104L. doi:10.1126/science.260.5111.1104. PMID 17806339. S2CID 46397540.

- Is the world’s oldest tree growing in a ravine in Chile? (Report). 2022-05-20. doi:10.1126/science.add1051.

- Hill, R. S.; Whang, S. S. (1996). "A new species of Fitzroya (Cupressaceae) from Oligocene sediments in north-western Tasmania". Australian Systematic Botany. 9 (6): 867. doi:10.1071/SB9960867.

- Villagrán, Carolina; Leon, Ana; Roig, Fidel A. (2004). "Paleodistribution of the alerce and cypres of the Guaitecas during the interstadial stages of the Llanquihue Glaciation: Llanquihue and Chiloé provinces, Los Lagos Region, Chile". Revista Geológica de Chile. 31 (1): 133–151. doi:10.4067/S0716-02082004000100008. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- Urbina, Ximena (2011). "Análisis Histórico-Cultural del alerce en la Patagonia Septentrional Occidental, Chiloé, siglos XVI al XIX" (PDF). Magallania. 39 (2): 57–73. doi:10.4067/S0718-22442011000200005.

- Torrejón g, F.; Cisternas v, M.; Alvial c, I.; Torres r, L. (2011). "Consecuencias de la tala maderera colonial en los bosques de alerce de Chiloé, sur de Chile (Siglos XVI-XIX)". Magallania (Punta Arenas). 39 (2): 75. doi:10.4067/S0718-22442011000200006.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, p. 225.

- Otero 2006, p. 73.

- Lara, A.; Fraver, S.; Aravena, J.C.; Wolodarsky-Franke, F. (1999), "Fire and the dynamics of Fitzroya cupressoides (alerce) forests of Chile's Cordillera Pelada", Écoscience, 6 (1): 100–109, doi:10.1080/11956860.1999.11952199, archived from the original on 2014-08-27

- Villalobos et al. 1974, p. 457.

- Otero 2006, p. 86.

- Devall, M. S.; Parresol, B. R.; Armesto, J. J. (1998). "Dendroecological analysis of a Fitzroya cupressoides and a Nothofagus nitida stand in the Cordillera Pelada, Chile". Forest Ecology and Management. 108 (1–2): 135–145. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(98)00221-7.

Bibliography

- Otero, Luis (2006). La huella del fuego: Historia de los bosques nativos. Poblamiento y cambios en el paisaje del sur de Chile. Pehuén Editores. ISBN 956-16-0409-4.

- Villalobos R., Sergio; Silva G., Osvaldo; Silva V., Fernando; Estelle M., Patricio (1974). Historia de Chile (1995 ed.). Editorial Universitaria. ISBN 956-11-1163-2.

- T.T. Veblen, B.R. Burns, T. Kitzberger, A. Lara and R. Villalba (1995) The ecology of the conifers of southern South America. Pages 120-155 in: N. Enright and R. Hill (eds.), Ecology of the Southern Conifers. Melbourne University Press.

External links

- Fitzroya cupressoides in Chilebosque Archived 2016-07-26 at the Wayback Machine (Spanish)

- Fitzroya cupressoides in Encyclopedia of the Chilean Flora (Spanish)

- Conifers Around the World: Fitzroya cupressoides – Alerce

- ents-bbs.org / Tall trees in Chile and Argentina?

- ents-bbs.org / Chile Trip Part 3: Parque Nacional Alerce Andino