Diselma

Diselma archeri (dwarf pine or Cheshunt pine)[2] is a species of plant of the family Cupressaceae and the sole species in the genus Diselma. It is endemic to the alpine regions of Tasmania's southwest and Central Highlands, on the western coast ranges and Lake St. Clair. It is a monotypic genus restricted to high altitude rainforest and moist alpine heathland. Its distribution mirrors very closely that of other endemic Tasmanian conifers Microcachrys tetragona and Pherosphaera hookeriana.

| Diselma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Gymnosperms |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Cupressales |

| Family: | Cupressaceae |

| Subfamily: | Callitroideae |

| Genus: | Diselma Hook.f. |

| Species: | D. archeri |

| Binomial name | |

| Diselma archeri Hook.f. | |

| Synonyms | |

Appearance and ecology

Diselma archeri is a compact, prostrate shrub which commonly reaches 1–4 m in height but has been recorded to reach greater heights in subalpine rainforest zones. The foliage has a grey-green appearance with branchlets curving downward at their tips. Branches are short, ridged and very numerous. Branchlet foliage appears square in cross-section and scale-like leaves (2–3 mm) are overlapping and arranged in opposite decussate pairs which are pressed close to the stem.[3] The square leaf arrangement is similar to that of Microcachrys tetragona (Podocarpaceae) (creeping pine) and the two species can easily be confused. However, M. tetragona lives up to its name and grows low to the ground, spreading out with only occasional erect branches. Another species which can be confused with Diselma is Phaerosphaera hookeriana (previously known as Microstrobos niphophilus ) which is in the family Podocarpaceae. Both these species have a similar growth habit and distribution, however, the opposite pairs of leaves on D. archeri again make it distinguishable from the other species.[4] Bark is rough and scaly and often weathered revealing a reddish-brown inner bark. Being a gymnosperm no flowers are produced, instead seed development occurs on the surface of the scale-like leaves which are modified to form cones (see image).[5]

Diselma archeri is a dioecious shrub, where male and female cones are located on separate individuals. Both types of cones are very small (3–4 mm) and occur at the branch tips. The female cone is composed of two pairs of opposite cone scales and only the upper pair of scales is fertile.[6] At maturity up to four small winged seeds are produced which are wind dispersed.[7] D. archeri seedlings are uncommon as the species often re-sprouts from roots and trunks buried in peat soils.[2]

Taxonomy

Diselma : dis (meaning double) and selma (meaning upper) is a reference to either the two fertile scales in the female cone or the arrangement of the overlapping leaves in the opposite alternating pairs. archeri is named after botanical collector William Archer (1820-1874) who was also a Fellow of the Linnaean Society, an architect and Member of Parliament for Deloraine, Tasmania.[8] This species is commonly known as dwarf pine in reference to its prostrate growth pattern or Cheshunt pine which is in reference to a property belonging to William Archer, although the species would not have occurred there.[9]

Distribution

Diselma archeri is endemic to Tasmania and is only found in high rainfall alpine and subalpine areas of the South West and Central Plateau of the state. Its altitudinal range varies from approximately 580-1400m above sea level. Like many Tasmanian conifers D. archeri is very fire sensitive and will only occur in fire free areas of alpine coniferous heath and montane rainforest.[11] This species can form a small tree (3-4m) in closed rainforest at high altitude and some ecologists consider Diselma to be one of the seven genera which can be used as rainforest indicators in Tasmania.[12] In more open coniferous heathland the Dwarf Pine grows more prostrate and only reaches approximately 1-2m in height.

Phylogeny

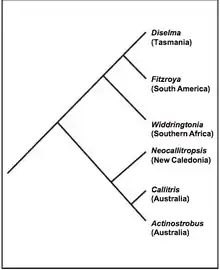

The closest relatives to Diselma appear to be the South American genus Fitzroya, another monotypic genus in the subfamily Callitroideae, the Southern Hemisphere clade of Cupressaceae.[10] Fossils of both Diselma and Fitzroya have been recorded in Tasmania.[13] This evidence indicates that Diselma archeri is most likely a paleoendemic and is the last remaining species in a genus that was once more extensive and has refuged to specific alpine zones due to changing climate.[14]

References

- Farjon, A. (2013). "Diselma archeri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T42225A2962853. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42225A2962853.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "Diselma archeri (Cupressaceae)". utas.edu.au. University of Tasmania. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- Kirkpatrick, J. 1997. Alpine Tasmania. An illustrated guide to the flora and vegetation. Oxford University Press" Melbourne. P. 18-19.

- "Key to Tasmanian Dicots".

- Raven, P.H., Evert, R.F., Eichorn, S.E. 2003. Biology of Plants. 6th Edition. W.H Freeman and Company

- Armin Jagel, Veit Dörken: Morphology and morphogenesis of the seed cones of the Cupressaceae - part III. Callitroideae. Bulletin of the Cupressus Conservation Project, Bd. 4(3), 2015, S. 91–103 (PDF)

- "Diselma archeri (Cheshunt pine) description".

- "Diselma archeri - Growing Native Plants".

- Wapstra, M., Wapstra, A., Wapstra, H. 2010. Tasmanian plant names unravelled. Fullers Bookshop Pty Ltd

- Gadek, D.A., Alpers, D.L., Heslewood, M.M. and Quinn, C.J. 2000. Relationships within the Cupressaceae sensu lato: A combined morphological and molecular approach. American Journal of Botany 87(7): 1044–1057

- "Key to Tasmanian Dicots".

- Jarmen. S.J., Brown, M.J. 1983. A definition of cool temperate rainforest in Tasmania. Search14. P. 81-87

- Jordan, G.J., Barnes, R. and Hill, R.S. 1995. An early to Middle Pleistocene Flora of subalpine affinities in lowland Western Tasmania. Australian Journal of Botany. 43. 231-242

- Jordan, G.J., Barnes, R. and Hill, R.S. 1995. An early to Middle Pleistocene Flora of subalpine affinities in lowland Western Tasmania. Australian Journal of Botany. 43. 231-242