Color photography

Color photography is photography that uses media capable of capturing and reproducing colors. By contrast, black-and-white or gray-monochrome photography records only a single channel of luminance (brightness) and uses media capable only of showing shades of gray.

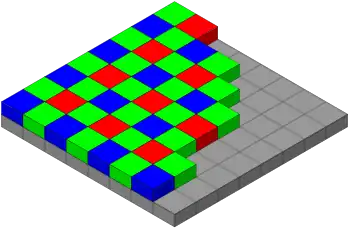

In color photography, electronic sensors or light-sensitive chemicals record color information at the time of exposure. This is usually done by analyzing the spectrum of colors into three channels of information, one dominated by red, another by green and the third by blue, in imitation of the way the normal human eye senses color. The recorded information is then used to reproduce the original colors by mixing various proportions of red, green and blue light (RGB color, used by video displays, digital projectors and some historical photographic processes), or by using dyes or pigments to remove various proportions of the red, green and blue which are present in white light (CMY color, used for prints on paper and transparencies on film).

Monochrome images which have been "colorized" by tinting selected areas by hand or mechanically or with the aid of a computer are "colored photographs", not "color photographs". Their colors are not dependent on the actual colors of the objects photographed and may be inaccurate.

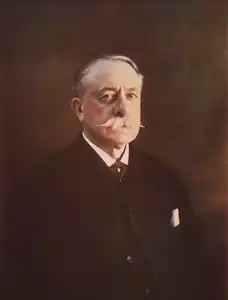

The foundation of all practical color processes, the three-color method was first suggested in an 1855 paper by Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell, with the first color photograph produced by Thomas Sutton for a Maxwell lecture in 1861.[1][2] Color photography has been the dominant form of photography since the 1970s, with monochrome photography mostly relegated to niche markets such as art photography.

History

Three-color processes

The three-color method, which is the foundation of virtually all practical color processes whether chemical or electronic, was first suggested in an 1855 paper on color vision by Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell.[1][2]

In his studies of color vision, Maxwell showed, by using a rotating disk with which he could alter the proportions, that any visible hue or gray tone could be made by mixing only three pure colors of light – red, green and blue – in proportions that would stimulate the three types of cells to the same degrees under particular lighting conditions.[3] To emphasize that each type of cell by itself did not actually see color but was simply more or less stimulated, he drew an analogy to black-and-white photography: if three colorless photographs of the same scene were taken through red, green and blue filters, and transparencies ("slides") made from them were projected through the same filters and superimposed on a screen, the result would be an image reproducing not only red, green and blue, but all of the colors in the original scene.[4]

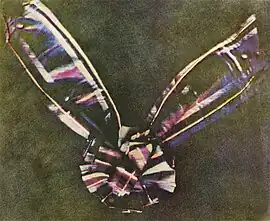

The first color photograph made according to Maxwell's prescription, a set of three monochrome "color separations", was taken by Thomas Sutton in 1861 for use in illustrating a lecture on color by Maxwell, where it was shown in color by the triple projection method.[5] The test subject was a bow made of ribbon with stripes of various colors, apparently including red and green. During the lecture about physics and physiology, not photography, Maxwell commented on the inadequacy of the results and the need for a photographic material more sensitive to red and green light. A century later, historians were mystified by the reproduction of any red at all because the photographic process used by Sutton was, for all practical purposes, insensitive to red light and only marginally sensitive to green. In 1961, researchers found that many red dyes also reflect ultraviolet light, coincidentally transmitted by Sutton's red filter, and surmised that the three images were probably due to ultra-violet, blue-green and blue wavelengths, rather than to red, green and blue.[6]

Screen-plate era

The Joly screen process emerged as a simpler and somewhat more economical alternative, requiring no specialized camera or viewer. Instead, it necessitated a unique color-compensating filter for the camera lens and a particular holder for the photographic plates. The core of the system resided within the holder: a clear glass plate meticulously ruled with fine lines of three colors, creating a consistent, repeating pattern across its entire surface. Rather than capturing three separate photographs through individual colored filters, this method employed numerous narrow strips (the colored lines) to allow the essential color information to be recorded in a single, composite image. After developing the negative, a positive transparency was produced, and a viewing screen—with red, green, and blue lines matching the taking screen's pattern—was precisely aligned and applied, rendering the colors visible. The transparency and screen were notably similar to the monochrome liquid crystal elements and overlay of ultra-thin red, green, and blue color filter stripes that generate the color image in a typical LCD display. This invention was attributed to Irish scientist John Joly, who, like many inventors, ultimately discovered that the fundamental concept had been preemptively outlined in Louis Ducos du Hauron's 1868 patent, which had since expired.[7]

A 1908 Autochrome Lumière photograph of American author Mark Twain.

A 1908 Autochrome Lumière photograph of American author Mark Twain. A 1914 color photograph of the Taj Mahal published in a 1921 issue of National Geographic magazine.

A 1914 color photograph of the Taj Mahal published in a 1921 issue of National Geographic magazine.

A 1917 Autochrome color photograph of a French Army lookout at his observation post during World War I.

A 1917 Autochrome color photograph of a French Army lookout at his observation post during World War I. House in Stockholm, Autochrome, 1930.

House in Stockholm, Autochrome, 1930. Autochrome dated 1934, the Royal Swedish Opera

Autochrome dated 1934, the Royal Swedish Opera

Agfacolor photo dated 1937, World exposition in Paris, France

Agfacolor photo dated 1937, World exposition in Paris, France An Agfacolor slide dated 1937 from café in Oslo, Norway.

An Agfacolor slide dated 1937 from café in Oslo, Norway. An Agfacolor slide dated 1938 from Sweden.

An Agfacolor slide dated 1938 from Sweden. Agfacolor photo dated 1938, Vaxholm in Sweden

Agfacolor photo dated 1938, Vaxholm in Sweden Kodachrome photo taken at the 1939 New York World's Fair

Kodachrome photo taken at the 1939 New York World's Fair Kodachrome photo by Chalmers Butterfield of Shaftesbury Avenue from Piccadilly Circus, in the West End of London, c. 1949

Kodachrome photo by Chalmers Butterfield of Shaftesbury Avenue from Piccadilly Circus, in the West End of London, c. 1949 John Canoe Festival celebrants, Kingston, Jamaica, Christmas 1975 (digitized from Kodachrome original)

John Canoe Festival celebrants, Kingston, Jamaica, Christmas 1975 (digitized from Kodachrome original) A sample shot of Polaroid Type 600, ISO 640, color film, 2009

A sample shot of Polaroid Type 600, ISO 640, color film, 2009

Digital photography

Artists' perspectives

Photographers differed in opinion about color photography when it was introduced. Some fully embraced it when it was available to the public in the late 1930s, while others remained skeptical of its relevance in photography.

Proponents

Paul Outerbridge was an American photographer prominent for his early use and experiments in color photography. He began writing a monthly column on color photography for the U.S. Camera Magazine around 1930. Outerbridge became known for the high quality of his color illustrations, made by a highly complex tri-color carbro process.[8] In 1940 he published his seminal book Photographing in Color, using high quality illustrations to explain his techniques.[9]

Ferenc Berko, a classic photographer who lived during the rise of color film, was one of the photographers who immediately recognized the potential of color film. He saw it as a new way to frame the world; a way to experiment with the subjects he photographed and how he conveyed emotion in the photograph.[10]

John Hedgecoe, another photographer who lived during this time period, was another example of those who preferred color. He published a book entitled The Art of Color Photography, which explained the importance of understanding the "special and often subtle relationships between different colors". He also described the psychological and emotional power of color on the viewer since certain colors, he argues, can make people feel a certain way.[11]

Skeptics

According to Eggleston, his former idol, Henri Cartier-Bresson, said to him at a party, “William, color is bullshit”, and then not another word.[12]

Harold Baquet, for instance—a relatively current photographer known best for documenting New Orleans civil rights—was not keen on color. He preferred to take pictures mainly using black-and-white film. When asked about his reasoning for this preference during an interview, he replied, “The less is more. Sometimes the color distracts from the essential subject. Sometimes, light, line, and form is enough, allowing you to explore the sculptural qualities of that third dimension, that illusional dimension of depth. And it’s fun”.[13] This aversion to color was due mainly to a fear of losing simplicity in his pictures. He worried that color gave the eye too much to take in.[13]

See also

- People

- Other topics

- Color motion picture film

- Color printing

- Color television

- Film colorization

- Hand-coloring (easily mistaken for early color photography)

- List of color film systems

- List of early color feature films

- List of photographs considered the most important

- Photochrome

- Photographic processes

- Potassium ferricyanide

- The Shackleton Expedition, on which Paget color photography was used (among other types)

- Timeline of historic inventions

Notes

References

- "1861: James Clerk Maxwell's greatest year". King's College London. 3 January 2017. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- "From Charles Mackintosh's waterproof to Dolly the sheep: 43 innovations Scotland has given the world". The independent. 30 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Maxwell, James Clerk (1855). "Experiments on colour, as perceived by the eye, with remarks on colour-blindness". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. XXI part II. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-07-06.

- Science progress in the twentieth century: a quarterly journal of scientific work & thought, Volume 2. John Murray. 1908. p. 359. Archived from the original on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 2016-10-10. (Note: in apparent deference to the primaries named by Thomas Young, Maxwell calls the short-wavelength primary "violet" in the relevant paragraphs of his 1855 paper, though he used blue in his experiments, which the paper also describes, and in his 1861 demonstration)

- "The first colour photograph, 1861". The Guardian. 3 January 2017. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- R.W.G. Hunt (2004). The Reproduction of Colour, 6th edition. Wiley. pp 9–10.

R.M. Evans (1961a). “Some Notes on Maxwell’s Colour Photograph.” Journal of Photographic Science 9. pp243–246

R.M. Evans (1961b). “Maxwell's Color Photography”. Scientific Photography 205. pp 117–128. - Joly, J: "On a method of photography in natural colors," Scientific Transactions of the Royal Dublin Society, October 1896, 6(2):127–138. This source provides details, such as the specific reasons for the unusual colors used in the taking screen and examples of the required exposures. The color illustrations underwent significant hand-work by the engravers and may have been entirely hand-colored, using the original transparencies as a guide. As noted on page 127, publication was delayed by more than a year. The 1895 date is confirmed by the publication of a lengthy abstract in Nature, November 28, 1895, 53(1361):91–93.

- Szarkowski, John (July 28, 1999). Looking at Photographs: 100 Pictures from the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Bulfinch.

- "When Color Was Vulgar: Paul Outerbridge's Avant-Gardist's Eye". The New Yorker. 5 August 2016. Archived from the original on 2018-09-21. Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- Honan, William (March 26, 2000). "Ferenc Berko, 84, Pioneer In Use of Color Photography". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Hedgecoe, John (1998). The Art of Color Photography. Reed Consumer Books.

- "Patrik Sandberg » WILLIAM EGGLESTON BY DREW BARRYMORE". www.patriksandberg.com. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- Tuley, Laura Camille (December 2007). "An Interview with Harold Baquet" (PDF). New Orleans Review. 33 (2): 108–116. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 17, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

General references

- Coe, Brian (1978). Colour Photography: the first hundred years 1840–1940. Ash & Grant.

- Coote, Jack (1993). The Illustrated History of Colour Photography. Fountain Press Ltd., ISBN 0-86343-380-4.

- Preservation of Photographs. Kodak publication, no. F-30. (1979). Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Co.

- Paine, C. (1996). Standards in the Museum Care of Photographic Collections. London, UK: Museums & Galleries Commission. ISBN 0-948630-42-6.

- Keefe, L.E.; & Inch, D. (1990). The Life of a Photograph: Archival processing, matting, framing, storage. Boston, MA: Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-80024-9, ISBN 978-0-240-80024-0.

- Lavédrine, B.; Gandolfo, J.-P.; Monod, S. (2003). A Guide to the Preventive Conservation of Photograph Collections. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Conservation Institute. ISBN 0-89236-701-6, ISBN 978-0-89236-701-6.

- Photograph Preservation and the Research Library. (1991). Mountain View, CA: The Research Libraries Group. ISBN 0-87985-212-7.

- Penichon, Sylvie (2013). Twentieth-Century Color Photographs: Identification and Care. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Publications. ISBN 978-1-60606-156-5.

- Reilly, J.M.; et al. (1998). Storage Guide for Color Photographic Materials. Albany, NY: University of the State of New York.

- Ritzenthaler, M.L.; Vogt-O'Connor, D. (2006). Photographs: Archival care and management. Chicago, IL: Society of American Archivists. ISBN 1-931666-17-2, ISBN 978-1-931666-17-6.

- Sipley, Louis Walton. (1951). A Half Century of Color, New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Caring for Photographs: Display, storage, restoration. Life library of photography. (1982). Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-4420-8.

- Weinstein, R.A.; Booth, L. (1977). Collection, Use, and Care of Historical Photographs. Nashville, TN: American Association for State and Local History. ISBN 0-910050-21-X.

- Wilhelm, H.G.; Brower, C. (1993). The Permanence and Care of Color Photographs: Traditional and digital color prints, color negatives, slides, and motion pictures. Grinnell, IA: Preservation Pub. Co. ISBN 0-911515-00-3.

- Wythe, D. (2004). Museum Archives: An introduction. Chicago, IL: Society of American Archivists. ISBN 1-931666-06-7, ISBN 978-1-931666-06-0.

Further reading

- Mathew Carey Lea in 1887 article appearing in Scientific American entitled "Photography in Natural Colors".[1]

- Rogers, David (October 2007), The Chemistry of Photography: From Classical to Digital Technologies, Royal Society of Chemistry, ISBN 9780854042739, OCLC 1184188382

- Scientific American. Munn & Company. 1887-07-09. p. 17.