Purple

Purple is a color similar in appearance to violet light. In the RYB color model historically used in the arts, purple is a secondary color created by combining red and blue pigments in different proportions. In the CMYK color model used in modern printing, purple is made by combining magenta pigment with either cyan pigment, black pigment, or both. In the RGB color model used in computer and television screens, purple is created by mixing red and blue light in order to create colors that appear similar to violet light.

| Purple | |

|---|---|

%252C_Wakehurst_Place%252C_UK_-_Diliff.jpg.webp)     | |

| Hex triplet | #800080 |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (128, 0, 128) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (300°, 100%, 50%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (30, 68, 308°) |

| Source | HTML color names |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) H: Normalized to [0–100] (hundred) | |

Purple has long been associated with royalty, originally because Tyrian purple dye—made from the secretions of sea snails—was extremely expensive in antiquity.[1] Purple was the color worn by Roman magistrates; it became the imperial color worn by the rulers of the Byzantine Empire and the Holy Roman Empire, and later by Roman Catholic bishops. Similarly in Japan, the color is traditionally associated with the emperor and aristocracy.[2]

According to contemporary surveys in Europe and the United States, purple is the color most often associated with rarity, royalty, luxury, ambition, magic, mystery, piety and spirituality.[3][4] When combined with pink, it is associated with eroticism, femininity, and seduction.[5]

Etymology and definitions

The modern English word purple comes from the Old English purpul, which derives from Latin purpura, which, in turn, derives from the Greek πορφύρα (porphura),[6] the name of the Tyrian purple dye manufactured in classical antiquity from a mucus secreted by the spiny dye-murex snail.[7][8] The first recorded use of the word purple dates to the late 900s AD.[7]

In art, history, and fashion

In prehistory and the ancient world: Tyrian purple

.jpg.webp)

Purple first appeared in prehistoric art during the Neolithic era. The artists of Pech Merle cave and other Neolithic sites in France used sticks of manganese and hematite powder to draw and paint animals and the outlines of their own hands on the walls of their caves. These works have been dated to between 16,000 and 25,000 BC.[9]

As early as the 15th century BC the citizens of Sidon and Tyre, two cities on the coast of Ancient Phoenicia (present day Lebanon), were producing purple dye from a sea snail called the spiny dye-murex.[10] Clothing colored with the Tyrian dye was mentioned in both the Iliad of Homer and the Aeneid of Virgil.[10] The deep, rich purple dye made from this snail became known as Tyrian purple.[11]

The process of making the dye was long, difficult and expensive. Thousands of the tiny snails had to be found, their shells cracked, the snail removed. Mountains of empty shells have been found at the ancient sites of Sidon and Tyre. The snails were left to soak, then a tiny gland was removed and the juice extracted and put in a basin, which was placed in the sunlight. There, a remarkable transformation took place. In the sunlight the juice turned white, then yellow-green, then green, then violet, then a red which turned darker and darker. The process had to be stopped at exactly the right time to obtain the desired color, which could range from a bright crimson to a dark purple, the color of dried blood. Then either wool, linen or silk would be dyed. The exact hue varied between crimson and violet, but it was always rich, bright and lasting.[12]

Tyrian purple became the color of kings, nobles, priests and magistrates all around the Mediterranean. It was mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament); in the Book of Exodus, God instructs Moses to have the Israelites bring him an offering including cloth "of blue, and purple, and scarlet,"[13] to be used in the curtains of the Tabernacle and the garments of priests. The term used for purple in the 4th-century Latin Vulgate version of the Bible passage is purpura or Tyrian purple.[14] In the Iliad of Homer, the belt of Ajax is purple, and the tails of the horses of Trojan warriors are dipped in purple. In the Odyssey, the blankets on the wedding bed of Odysseus are purple. In the poems of Sappho (6th century BC) she celebrates the skill of the dyers of the Greek kingdom of Lydia who made purple footwear, and in the play of Aeschylus (525–456 BC), Queen Clytemnestra welcomes back her husband Agamemnon by decorating the palace with purple carpets. In 950 BC, King Solomon was reported to have brought artisans from Tyre to provide purple fabrics to decorate the Temple of Jerusalem.[15]

Alexander the Great (when giving imperial audiences as the basileus of the Macedonian Empire), the basileus of the Seleucid Empire, and the kings of Ptolemaic Egypt all wore Tyrian purple.

The Roman custom of wearing purple togas may have come from the Etruscans; an Etruscan tomb painting from the 4th century BC shows a nobleman wearing a deep purple and embroidered toga.

In Ancient Rome, the Toga praetexta was an ordinary white toga with a broad purple stripe on its border. It was worn by freeborn Roman boys who had not yet come of age,[16] curule magistrates,[17][18] certain categories of priests,[19] and a few other categories of citizens.

The Toga picta was solid purple, embroidered with gold. During the Roman Republic, it was worn by generals in their triumphs, and by the Praetor Urbanus when he rode in the chariot of the gods into the circus at the Ludi Apollinares.[20] During the Empire, the toga picta was worn by magistrates giving public gladiatorial games, and by the consuls, as well as by the emperor on special occasions.

During the Roman Republic, when a triumph was held, the general being honored wore an entirely purple toga bordered in gold, and Roman Senators wore a toga with a purple stripe. However, during the Roman Empire, purple was more and more associated exclusively with the emperors and their officers.[21] Suetonius claims that the early emperor Caligula had the King of Mauretania murdered for the splendour of his purple cloak, and that Nero forbade the use of certain purple dyes.[22] In the late empire the sale of purple cloth became a state monopoly protected by the death penalty.[23]

According to the New Testament, Jesus Christ, in the hours leading up to his crucifixion, was dressed in purple (πορφύρα: porphura) by the Roman garrison to mock his claim to be 'King of the Jews'.[24]

The actual color of Tyrian purple seems to have varied from a reddish to a bluish purple. According to the Roman writer Vitruvius, (1st century BC), the murex shells coming from northern waters, probably Bolinus brandaris, produced a more bluish color than those of the south, probably Hexaplex trunculus. The most valued shades were said to be those closer to the color of dried blood, as seen in the mosaics of the robes of the Emperor Justinian in Ravenna. The chemical composition of the dye from the murex is close to that of the dye from indigo, and indigo was sometimes used to make a counterfeit Tyrian purple, a crime which was severely punished. What seems to have mattered about Tyrian purple was not its color, but its luster, richness, its resistance to weather and light, and its high price.[25]

In modern times, Tyrian purple has been recreated, at great expense. When the German chemist Paul Friedander tried to recreate Tyrian purple in 2008, he needed twelve thousand mollusks to create 1.4 ounces of dye, enough to color a handkerchief. In the year 2000, a gram of Tyrian purple made from ten thousand mollusks according to the original formula cost two thousand euros.[26][27]

China

In ancient China, purple was obtained not through the Mediterranean mollusc, but purple gromwell. The dye obtained did not easily adhere to fabrics, making purple fabrics expensive. Purple became a fashionable color in the state of Qi (齊, 1046 BC–221 BC) because its ruler, Qin Shi Huang, developed a preference for it. As a result, the price of purple fabric was over five times that of plain fabric. His minister, Guan Zhong (管仲), eventually convinced him to relinquish this preference.

China was the first culture to develop a synthetic purple color.[28]

An old hypothesis suggested links between the Chinese purple and blue and Egyptian blue, however, molecular structure analysis and evidence such as the absence of lead in Egyptian blue and the lack of examples of Egyptian blue in China, argued against the hypothesis.[29][30] The use of quartz, barium, and lead components in ancient Chinese glass and Han purple and Han blue has been used to suggest a connection between glassmaking and the manufacture of pigments,[31] and to prove the independence of the Chinese invention.[29] Taoist alchemists may have developed Han purple from their knowledge of glassmaking.[29]

Lead is used by the pigment maker to lower the melting point of the barium in Han Purple.[32]

Purple was regarded as a secondary color in ancient China. In classical times, secondary colors were not as highly prized as the five primary colors of the Chinese spectrum, and purple was used to allude to impropriety, in contrast to crimson, which was deemed a primary color and symbolized legitimacy. Nevertheless, by the 6th century AD, purple was ranked above crimson. Several changes to the ranks of colors occurred after that time.

An Egyptian bowl colored with Egyptian blue, with motifs painted in dark manganese purple. (between 1550 and 1450 BC)

An Egyptian bowl colored with Egyptian blue, with motifs painted in dark manganese purple. (between 1550 and 1450 BC) Painting of a man wearing an all-purple toga picta, from an Etruscan tomb (about 350 BC).

Painting of a man wearing an all-purple toga picta, from an Etruscan tomb (about 350 BC). Roman men wearing togae praetextae with reddish-purple stripes during a religious procession (1st century BC).

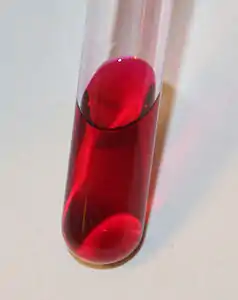

Roman men wearing togae praetextae with reddish-purple stripes during a religious procession (1st century BC)..jpg.webp) Different purple hues obtained from three types of sea snails

Different purple hues obtained from three types of sea snails Dye bath of Tyrian purple

Dye bath of Tyrian purple Cloth dyed with Tyrian purple. The color could vary from crimson to deep purple, depending upon the type of murex sea-snail and how it was made.

Cloth dyed with Tyrian purple. The color could vary from crimson to deep purple, depending upon the type of murex sea-snail and how it was made.

Purple in the Byzantine Empire and Carolingian Europe

Through the early Christian era, the rulers of the Byzantine Empire continued the use of purple as the imperial color, for diplomatic gifts, and even for imperial documents and the pages of the Bible. Gospel manuscripts were written in gold lettering on parchment that was colored Tyrian purple.[33] Empresses gave birth in the Purple Chamber, and the emperors born there were known as "born to the purple," to separate them from emperors who won or seized the title through political intrigue or military force. Bishops of the Byzantine church wore white robes with stripes of purple, while government officials wore squares of purple fabric to show their rank.

In western Europe, the Emperor Charlemagne was crowned in 800 wearing a mantle of Tyrian purple, and was buried in 814 in a shroud of the same color, which still exists (see below). However, after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the color lost its imperial status. The great dye works of Constantinople were destroyed, and gradually scarlet, made with dye from the cochineal insect, became the royal color in Europe.[34]

_v2.jpg.webp) The Empress Theodora, the wife of the Emperor Justinian I, dressed in Tyrian purple. (6th century).

The Empress Theodora, the wife of the Emperor Justinian I, dressed in Tyrian purple. (6th century).

A medieval depiction of the coronation of the Emperor Charlemagne in 800. The bishops and cardinals wear purple, and the Pope wears white.

A medieval depiction of the coronation of the Emperor Charlemagne in 800. The bishops and cardinals wear purple, and the Pope wears white. A fragment of the shroud in which the Emperor Charlemagne was buried in 814. It was made of gold and Tyrian purple from Constantinople.

A fragment of the shroud in which the Emperor Charlemagne was buried in 814. It was made of gold and Tyrian purple from Constantinople.

The Middle Ages and Renaissance

In 1464, Pope Paul II decreed that cardinals should no longer wear Tyrian purple, and instead wear scarlet, from kermes and alum,[35] since the dye from Byzantium was no longer available. Bishops and archbishops, of a lower status than cardinals, were assigned the color purple, but not the rich Tyrian purple. They wore cloth dyed first with the less expensive indigo blue, then overlaid with red made from kermes dye.[36][37]

While purple was worn less frequently by Medieval and Renaissance kings and princes, it was worn by the professors of many of Europe's new universities. Their robes were modeled after those of the clergy, and they often wore square/violet or purple/violet caps and robes, or black robes with purple/violet trim. Purple/violet robes were particularly worn by students of divinity.

Purple and violet also played an important part in the religious paintings of the Renaissance. Angels and the Virgin Mary were often portrayed wearing purple or violet robes.

A 12th-century painting of Saint Peter consecrating Hermagoras, wearing purple, as a bishop.

A 12th-century painting of Saint Peter consecrating Hermagoras, wearing purple, as a bishop. In the Ghent Altarpiece (1422) by Jan van Eyck, the popes and bishops are wearing purple robes.

In the Ghent Altarpiece (1422) by Jan van Eyck, the popes and bishops are wearing purple robes..jpg.webp) A purple-clad angel from the Resurrection of Christ by Raphael (1483–1520)

A purple-clad angel from the Resurrection of Christ by Raphael (1483–1520)

18th and 19th centuries

In the 18th century, purple was still worn on occasion by Catherine the Great and other rulers, by bishops and, in lighter shades, by members of the aristocracy, but rarely by ordinary people, because of its high cost. But in the 19th century, that changed.

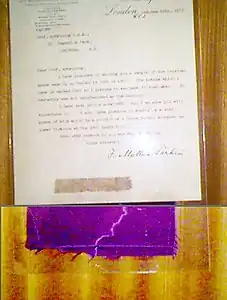

In 1856, an eighteen-year-old British chemistry student named William Henry Perkin was trying to make a synthetic quinine. His experiments produced instead the first synthetic aniline dye, a purple shade called mauveine, shortened simply to mauve. It took its name from the mallow flower, which is the same color.[38] The new color quickly became fashionable, particularly after Queen Victoria wore a silk gown dyed with mauveine to the Royal Exhibition of 1862. Prior to Perkin's discovery, mauve was a color which only the aristocracy and rich could afford to wear. Perkin developed an industrial process, built a factory, and produced the dye by the ton, so almost anyone could wear mauve. It was the first of a series of modern industrial dyes which completely transformed both the chemical industry and fashion.[39]

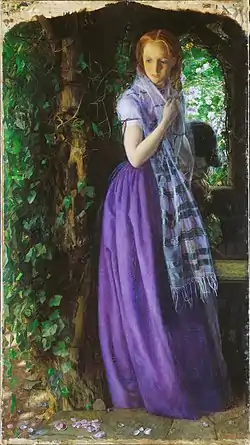

Purple was popular with the pre-Raphaelite painters in Britain, including Arthur Hughes, who loved bright colors and romantic scenes.

Queen Anne of Great Britain in golden dress and a purple velvet and ermine mantle (1705)

Queen Anne of Great Britain in golden dress and a purple velvet and ermine mantle (1705).jpg.webp) King Gustav III of Sweden (1779)

King Gustav III of Sweden (1779)_2.jpg.webp) Portrait of Empress Catherine the Great of Russia, by Fyodor Rokotov. (State Hermitage Museum).

Portrait of Empress Catherine the Great of Russia, by Fyodor Rokotov. (State Hermitage Museum). Empress Teresa Cristina of Brazil with her children (1849)

Empress Teresa Cristina of Brazil with her children (1849) In England, pre-Raphaelite painters like Arthur Hughes were particularly enchanted by purple and violet. This is April Love (1856).

In England, pre-Raphaelite painters like Arthur Hughes were particularly enchanted by purple and violet. This is April Love (1856). Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil (in dark purple dress) with her husband Prince Gaston and their son, the Prince of Grão-Pará at purple dusk (1877)

Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil (in dark purple dress) with her husband Prince Gaston and their son, the Prince of Grão-Pará at purple dusk (1877) Order of Leopold founded in 1830.

Order of Leopold founded in 1830.

20th and 21st centuries

At the turn of the century, purple was a favorite color of the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt, who flooded his pictures with sensual purples and violets.

In the 20th century, purple retained its historic connection with royalty; George VI (1896–1952), wore purple in his official portrait, and it was prominent in every feature of the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953, from the invitations to the stage design inside Westminster Abbey. But at the same time, it was becoming associated with social change; with the Women's Suffrage movement for the right to vote for women in the early decades of the century, with Feminism in the 1970s, and with the psychedelic drug culture of the 1960s.

In the early 20th century, purple, green, and white were the colors of the Women's Suffrage movement, which fought to win the right to vote for women, finally succeeding with the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920. Later, in the 1970s, in a tribute to the Suffragettes, it became the color of the women's liberation movement.[40]

In the concentration camps of Nazi Germany, prisoners who were members of non-conformist religious groups, such as the Jehovah's Witnesses, were required to wear a purple triangle.[41]

During the 1960s and early 1970s, it was also associated with counterculture, psychedelics, and musicians like Jimi Hendrix with his 1967 song "Purple Haze", or the English rock band of Deep Purple which formed in 1968. Later, in the 1980s, it was featured in the song and album Purple Rain (1984) by the American musician Prince.

The Purple Rain Protest was a protest against apartheid that took place in Cape Town, South Africa on 2 September 1989, in which a police water cannon with purple dye sprayed thousands of demonstrators. This led to the slogan The Purple Shall Govern.

The violet or purple necktie became very popular at the end of the first decade of the 21st century, particularly among political and business leaders. It combined the assertiveness and confidence of a red necktie with the sense of peace and cooperation of a blue necktie, and it went well with the blue business suit worn by most national and corporate leaders.[42]

Gustav Klimt portrait of woman with a purple hat (1912).

Gustav Klimt portrait of woman with a purple hat (1912)..jpg.webp) Serbian Orthodox bishop in mandyas (1923).

Serbian Orthodox bishop in mandyas (1923). George VI (1895–1952) wore purple in his official portrait.

George VI (1895–1952) wore purple in his official portrait. The coronation portrait of Elizabeth II and Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (1953) has three different shades of purple in the train, curtains and crown.

The coronation portrait of Elizabeth II and Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (1953) has three different shades of purple in the train, curtains and crown. Program from the Woman Suffrage Procession, a 1913 Women's Suffrage march.

Program from the Woman Suffrage Procession, a 1913 Women's Suffrage march. A pennant from the Women's Suffrage movement in the state of Indiana.

A pennant from the Women's Suffrage movement in the state of Indiana. Symbol of the Feminist movement in the United States (1970s). The purple color was chosen as a tribute to the Suffragette movement a half-century earlier.

Symbol of the Feminist movement in the United States (1970s). The purple color was chosen as a tribute to the Suffragette movement a half-century earlier.

In science and nature

Optics

The meanings of the color terms violet and purple varies even among native speakers of English, for example between United Kingdom and United States.[43] Optics research on purple and violet contains contributions of authors from different countries and different native languages, it is likely to be inconsistent in the use and meaning of the two colors. According to some speakers/authors of English, purple, unlike violet, is not one of the colors of the visible spectrum.[44] It was not one of the colors of the rainbow identified by Isaac Newton. According to some authors, purple does not have its own wavelength of light. For this reason, it is sometimes called a non-spectral color. It exists in culture and art, but not, in the same way that violet does, in optics. According to some speakers of English, purple is simply a combination, in various proportions, of two primary colors, red and blue.[45] According to other speakers of English, the same range of colors is called violet.[46]

In some textbooks of color theory, and depending on the geographical-cultural origin of the author, a "purple" is defined as any non-spectral color between violet and red (excluding violet and red themselves).[47] In that case, the spectral colors violet and indigo would not be shades of purple. For other speakers of English, these colors are shades of purple.

In the traditional color wheel long used by painters, purple is placed between crimson and violet.[48] However, also here there is much variation in color terminology depending on cultural background of the painters and authors, and sometimes the term violet is used and placed in between red and blue on the traditional color wheel. In a slightly different variation, on the color wheel, purple is placed between magenta and violet. This shade is sometimes called electric purple (See shades of purple).[49]

In the RGB color model, named for the colors red, green, and blue, used to create all the colors on a computer screen or television, the range of purples is created by mixing red and blue light of different intensities on a black screen. The standard HTML color purple is created by red and blue light of equal intensity, at a brightness that is halfway between full power and darkness.

In color printing, purple is sometimes represented by the color magenta, or sometimes by mixing magenta with red or blue. It can also be created by mixing just red and blue alone, but in that case the purple is less bright, with lower saturation or intensity. A less bright purple can also be created with light or paint by adding a certain quantity of the third primary color (green for light or yellow for pigment).

Relationship with violet

Purple is closely associated with violet. In common usage, both refer to a variety of colors between blue and red in hue.[50][51][52] Historically, purple has tended to be used for redder hues and violet for bluer hues.[50][53][54] In optics, violet is a spectral color; it refers to the color of any different single wavelength of light on the short wavelength end of the visible spectrum, between approximately 380 and 450 nanometers,[55] whereas purple is the color of various combinations of red, blue, and violet light,[47][52] some of which humans perceive as similar to violet.

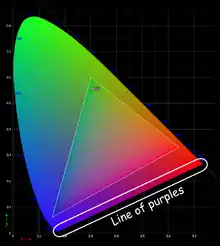

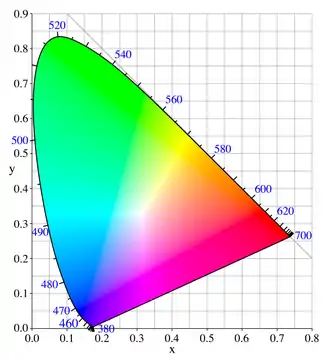

On a chromaticity diagram, the straight line connecting the extreme spectral colors (red and violet) is known as the line of purples (or 'purple boundary'); it represents one limit of human color perception. The color magenta used in the CMYK printing process is near the center of the line of purples, but most people associate the term "purple" with a somewhat bluer tone, such as is displayed by the color "electric purple" (a color also directly on the line of purples), shown below.

On the CIE xy chromaticity diagram, violet is on the curved edge in the lower left, while purples are on the straight line connecting the extreme colors red and violet; this line is known as the line of purples, or the purple line.[56][57]

On a computer or television screen, purple colors are created by mixing red and blue light. This is called the RGB color model.

On a computer or television screen, purple colors are created by mixing red and blue light. This is called the RGB color model.

Pigments

- Hematite and manganese are the oldest pigments used for the color purple. They were used by Neolithic artists in the form of sticks, like charcoal, or ground and powdered and mixed with fat, and used as a paint. Hematite is a reddish iron oxide which, when ground coarsely, makes a purple pigment. One such pigment is caput mortuum, whose name is also used in reference to mummy brown. The latter is another pigment containing hematite and historically produced with the use of mummified corpses.[58] Some of its compositions produce a purple color and may be called "mummy violet".[59] Manganese was also used in Roman times to color glass purple.[60]

- Han purple was the first synthetic purple pigment, invented in China in about 700 BC. It was used in wall paintings and pottery and other applications. In color, it was very close to indigo, which had a similar chemical structure. Han purple was very unstable, and sometimes was the result of the chemical breakdown of Han blue.

During the Middle Ages, artists usually made purple by combining red and blue pigments; most often blue azurite or lapis-lazuli with red ochre, cinnabar, or minium. They also combined lake colors made by mixing dye with powder; using woad or indigo dye for the blue, and dye made from cochineal for the red.[61]

- Cobalt violet was the first modern synthetic color in the purple family, manufactured in 1859. It was found, along with cobalt blue, in the palette of Claude Monet, Paul Signac, and Georges Seurat. It was stable, but had low tinting power and was expensive, so quickly went out of use.[62]

- Manganese violet was a stronger color than cobalt violet, and replaced it on the market.

- Quinacridone violet, one of a modern synthetic organic family of colors, was discovered in 1896 but not marketed until 1955. It is sold today under a number of brand names.

A sample of purpurite, or manganese phosphate, from the Packrat Mine in Southern California.

A sample of purpurite, or manganese phosphate, from the Packrat Mine in Southern California. A swatch of cobalt violet, popular among the French impressionists.

A swatch of cobalt violet, popular among the French impressionists. Manganese violet is a synthetic pigment invented in the mid-19th century.

Manganese violet is a synthetic pigment invented in the mid-19th century. Quinacridone violet, a synthetic organic pigment sold under many different names.

Quinacridone violet, a synthetic organic pigment sold under many different names.

Dyes

The most famous purple dye in the ancient world was Tyrian purple, made from a type of sea snail called the murex, found around the Mediterranean. (See history section above).[44]

In western Polynesia, residents of the islands made a purple dye similar to Tyrian purple from the sea urchin. In Central America, the inhabitants made a dye from a different sea snail, the purpura, found on the coasts of Costa Rica and Nicaragua. The Mayans used this color to dye fabric for religious ceremonies, while the Aztecs used it for paintings of ideograms, where it symbolized royalty.[61]

In the Middle Ages, those who worked with blue and black dyes belonged to separate guilds from those who worked with red and yellow dyes, and were often forbidden to dye any other colors than those of their own guild.[63] Most purple fabric was made by the dyers who worked with red, and who used dye from madder or cochineal, so Medieval violet colors were inclined toward red.

Orcein, or purple moss, was another common purple dye. It was known to the ancient Greeks and Hebrews, and was made from a Mediterranean lichen called archil or dyer's moss (Roccella tinctoria), combined with an ammoniac, usually urine. Orcein began to achieve popularity again in the 19th century, when violet and purple became the color of demi-mourning, worn after a widow or widower had worn black for a certain time, before he or she returned to wearing ordinary colors.[64]

From the Middle Ages onward, purple dyes for the clothing of common people were often made from the blackberry or other red fruit of the genus rubus, or from the mulberry. All of these dyes were more reddish than bluish, and faded easily with washing and exposure to sunlight.

A popular new dye which arrived in Europe from the New World during the Renaissance was made from the wood of the logwood tree (Haematoxylum campechianum), which grew in Spanish Mexico. Depending on the different minerals added to the dye, it produced a blue, red, black or, with the addition of alum, a purple color, It made a good color, but, like earlier dyes, it did not resist sunlight or washing.

In the 18th century, chemists in England, France and Germany began to create the first synthetic dyes. Two synthetic purple dyes were invented at about the same time. Cudbear is a dye extracted from orchil lichens that can be used to dye wool and silk, without the use of mordant. Cudbear was developed by Dr Cuthbert Gordon of Scotland: production began in 1758, The lichen is first boiled in a solution of ammonium carbonate. The mixture is then cooled and ammonia is added and the mixture is kept damp for 3–4 weeks. Then the lichen is dried and ground to powder. The manufacture details were carefully protected, with a ten-feet high wall being built around the manufacturing facility, and staff consisting of Highlanders sworn to secrecy.

French purple was developed in France at about the same time. The lichen is extracted by urine or ammonia. Then the extract is acidified, the dissolved dye precipitates and is washed. Then it is dissolved in ammonia again, the solution is heated in air until it becomes purple, then it is precipitated with calcium chloride; the resulting dye was more solid and stable than other purples.

Cobalt violet is a synthetic pigment that was invented in the second half of the 19th century, and is made by a similar process as cobalt blue, cerulean blue and cobalt green. It is the violet pigment most commonly used today by artists. In spite of its name, this pigment produces a purple rather than violet color [43]

Mauveine, also known as aniline purple and Perkin's mauve, was the first synthetic organic chemical dye,[65][66] discovered serendipitously in 1856. Its chemical name is 3-amino-2,±9-dimethyl-5-phenyl-7-(p-tolylamino)phenazinium acetate.

Fuchsine was another synthetic dye made shortly after mauveine. It produced a brilliant fuchsia color.

In the 1950s, a new family of purple and violet synthetic organic pigments called quinacridone came onto the market. It had originally been discovered in 1896, but were not synthesized until 1936, and not manufactured until the 1950s. The colors in the group range from deep red to bluish purple in color, and have the molecular formula C20H12N2O2. They have strong resistance to sunlight and washing, and are widely used today in oil paints, water colors, and acrylics, as well as in automobile coatings and other industrial coatings.

Blackberries were sometimes used to make purple dye in the Middle Ages.

Blackberries were sometimes used to make purple dye in the Middle Ages. This lichen, growing on a tree in Scotland, was used in the 18th century to make a common purple dye called Cudbear.

This lichen, growing on a tree in Scotland, was used in the 18th century to make a common purple dye called Cudbear. A sample of silk dyed with the original mauveine dye.

A sample of silk dyed with the original mauveine dye. A sample of fuchsine dye

A sample of fuchsine dye

Animals

The male violet-backed starling sports a very bright, iridescent purple plumage.

The male violet-backed starling sports a very bright, iridescent purple plumage. The purple frog is a species of amphibian found in India.

The purple frog is a species of amphibian found in India. Pseudanthias pascalus or purple queenfish.

Pseudanthias pascalus or purple queenfish. The purple sea urchin from Mexico.

The purple sea urchin from Mexico. A purple heron in flight (South Africa).

A purple heron in flight (South Africa). A purple finch (North America).

A purple finch (North America). The Lorius domicella, or purple-naped lory, from Indonesia.

The Lorius domicella, or purple-naped lory, from Indonesia.

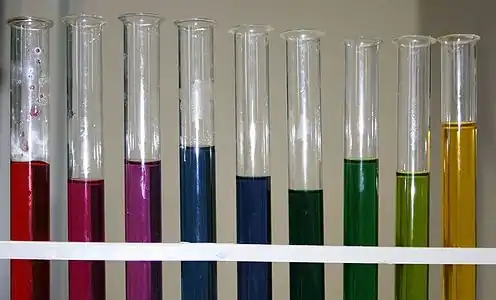

Anthocyanins

Certain grapes, eggplants, pansies and other fruits, vegetables and flowers may appear purple due to the presence of natural pigments called anthocyanins. These pigments are found in the leaves, roots, stems, vegetables, fruits and flowers of all plants. They aid photosynthesis by blocking harmful wavelengths of light that would damage the leaves. In flowers, the purple anthocyanins help attract insects who pollinate the flowers. Not all anthocyanins are purple; they vary in color from red to purple to blue, green, or yellow, depending upon the level of their pH.

The purple colors of this cauliflower, grapes, fruits, vegetables and flowers comes from natural pigments called anthocyanins.

The purple colors of this cauliflower, grapes, fruits, vegetables and flowers comes from natural pigments called anthocyanins. Anthocyanins range in color from red to purple to green, blue and yellow, depending upon the level of their pH.

Anthocyanins range in color from red to purple to green, blue and yellow, depending upon the level of their pH. Anthocyanins also account for the purple color in these copper beech trees, and in purple autumn leaves.

Anthocyanins also account for the purple color in these copper beech trees, and in purple autumn leaves. Anthocyanins produce the purple color in blood oranges.

Anthocyanins produce the purple color in blood oranges. A purple pansy.

A purple pansy..jpg.webp) "Blue" hydrangea is often actually purple.

"Blue" hydrangea is often actually purple.

Plants and flowers

- Purple needlegrass is the state grass of California.

Iris germanica flowers

Iris germanica flowers Syringa vulgaris, or lilac blossoms

Syringa vulgaris, or lilac blossoms Medicago sativa, known as alfalfa in the U.S. and lucerne in the U.K.

Medicago sativa, known as alfalfa in the U.S. and lucerne in the U.K. The Aster alpinus, or alpine aster, is native to the European mountains, including the Alps, while a subspecies is found in Canada and the United States.

The Aster alpinus, or alpine aster, is native to the European mountains, including the Alps, while a subspecies is found in Canada and the United States. Lavender flowers.

Lavender flowers. A purple rose.

A purple rose. Wisteria is a pale purple color.

Wisteria is a pale purple color..jpg.webp)

Microbiology

- Purple bacteria are bacteria that are phototrophic, that is, capable of producing energy through photosynthesis.[67]

- In April 2007 it was suggested that early archaea may have used retinal, a purple pigment, instead of chlorophyll, to extract energy from the sun. If so, large areas of the ocean and shoreline would have been colored purple; this is called the Purple Earth hypothesis.[68]

Astronomy

- One of the stars in the Pleiades, called Pleione, is sometimes called Purple Pleione because, being a fast spinning star, it has a purple hue caused by its blue-white color being obscured by a spinning ring of electrically excited red hydrogen gas.[69]

- The Purple Forbidden enclosure is a name used in traditional Chinese astronomy for those Chinese constellations that surround the north celestial pole.

Geography

- Purple Mountain is located on the eastern side of Nanjing. Its peaks are often found enveloped in purple clouds at dawn and dusk, hence comes its name "Purple Mountain". The Purple Mountain Observatory is located there.

- Purple Mountain in County Kerry, Ireland, takes its name from the color of the shivered slate on its summit.

- Purple Mountain in Wyoming (el. 8,392 feet (2,558 m)) is a mountain peak in the southern section of the Gallatin Range in Yellowstone National Park.

- Purple Mountain, Alaska

- Purple Mountain, Oregon

- Purple Mountain, Washington

- Purple Peak, Colorado

Purple Mountain near Killarney, Ireland.

Purple Mountain near Killarney, Ireland.

Purple Mountain, Nanjing.

Purple Mountain, Nanjing.

Purple mountains phenomenon

It has been observed that the greater the distance between a viewers eyes and mountains, the lighter and more blue or purple they will appear. This phenomenon, long recognized by Leonardo da Vinci and other painters, is called aerial perspective or atmospheric perspective. The more distant the mountains are, the less contrast the eye sees between the mountains and the sky.

The bluish color is caused by an optical effect called Rayleigh scattering. The sunlit sky is blue because air scatters short-wavelength light more than longer wavelengths. Since blue light is at the short wavelength end of the visible spectrum, it is more strongly scattered in the atmosphere than long wavelength red light. The result is that the human eye perceives blue when looking toward parts of the sky other than the sun.[70]

At sunrise and sunset, the light is passing through the atmosphere at a lower angle, and traveling a greater distance through a larger volume of air. Much of the green and blue is scattered away, and more red light comes to the eye, creating the colors of the sunrise and sunset and making the mountains look purple.

The phenomenon is referenced in the song "America the Beautiful", where the lyrics refer to "purple mountains' majesty" among other features of the United States landscape. A Crayola crayon called Purple Mountain Majesty in reference to the lyric was first formulated in 1993.

The more distant mountains are, the lighter and more blue they are. This is called atmospheric perspective or aerial perspective.

The more distant mountains are, the lighter and more blue they are. This is called atmospheric perspective or aerial perspective.

Mythology

Julius Pollux, a Greek grammarian who lived in the second century AD, attributed the discovery of purple to the Phoenician god and guardian of the city of Tyre, Heracles.[71] According to his account, while walking along the shore with the nymph Tyrus, the god's dog bit into a murex shell, causing his mouth to turn purple. The nymph subsequently requested that Heracles create a garment for her of that same color, with Heracles obliging her demands giving birth to Tyrian purple.[71][38]

Associations and symbolism

Royalty

In Europe, since some Roman emperors wore a Tyrian purple (purpura) toga praetexta, purple has been the color most associated with power and royalty.[44] The British Royal Family and other European royalty still use it as a ceremonial color on special occasions.[72] In Japan, purple is associated with the emperor and Japanese aristocracy.[2]

A purple postage stamp honored Queen Elizabeth II in 1958

A purple postage stamp honored Queen Elizabeth II in 1958.jpg.webp) Queen Margrethe II of Denmark in 2010.

Queen Margrethe II of Denmark in 2010.

Piety, faith, penitence, and theology

In the West, purple or violet is a color often associated with piety and religious faith.[72][73] In AD 1464, shortly after the Muslim conquest of Constantinople, which terminated the supply of Tyrian purple to Roman Catholic Europe, Pope Paul II decreed that cardinals should henceforth wear scarlet instead of purple, the scarlet being dyed with expensive cochineal. Bishops were assigned the color amaranth, being a pale and pinkish purple made then from a less-expensive mixture of indigo and cochineal.

In the Latin liturgical rites of the Catholic liturgy, purple represents penitence; Anglican and Catholic priests wear a purple stole when they hear confession and a purple stole and chasuble during Advent and Lent. Since the Second Vatican Council of 1962–5, priests may wear purple vestments, but may still wear black ones, when officiating at funerals. The Roman Missal permits black, purple (violet), or white vestments for the funeral Mass. White is worn when a child dies before the age of reason. Students and faculty of theology also wear purple academic dress for graduations and other university ceremonies.

Purple is also often worn by senior pastors of Protestant churches and bishops of the Anglican Communion.

Katharine Jefferts Schori, Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church of the United States

Katharine Jefferts Schori, Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church of the United States Bishop Mercurius of Zaraisk wearing an episcopal mantle (Saint Nicholas Russian Orthodox Cathedral, New York).

Bishop Mercurius of Zaraisk wearing an episcopal mantle (Saint Nicholas Russian Orthodox Cathedral, New York).

The color purple is also associated with royalty in Christianity, being one of the three traditional offices of Jesus Christ, i. e. king, although such a symbolism was assumed from the earlier Roman association or at least also employed by the ancient Romans.

Vanity, extravagance, individualism

In Europe and America, purple is the color most associated with vanity, extravagance, and individualism. Among the seven deadly sins, it represents pride. It is a color which is used to attract attention.[74]

The artificial, materialism and beauty

Purple is the color most often associated with the artificial and the unconventional. It is the major color that occurs the least frequently in nature, and was the first color to be synthesized.[75]

Ambiguity and ambivalence

Purple is the color most associated with ambiguity. Like other colors made by combining two primary colors, it is seen as uncertain and equivocal.[76]

In culture and society

Cultures of Asian countries

- The Chinese word for purple, zi, is connected with the North Star, Polaris, or zi Wei in Chinese. In Chinese astrology, the North Star was the home of the Celestial Emperor, the ruler of the heavens. The area around the North Star is called the Purple Forbidden Enclosure in Chinese astronomy. For that reason the Forbidden City in Beijing was also known as the Purple Forbidden City (zi Jin cheng). Purple often represents "the highest," holiest, and "most sacred values" in China.[73]

- In Taoism, purple is a transitional color and metaphysically between yin and yang.[73]

- Purple was a popular color introduced into Japanese dress during the Heian period (794–1185). The dye was made from the root of the alkanet plant (Anchusa officinalis), also known as murasaki in Japanese. At about the same time, Japanese painters began to use a pigment made from the same plant.[78]

- In Thailand, widows in mourning wear the color purple. Purple is also associated with Saturday on the Thai solar calendar.

Han purple and Han blue were synthetic colors made by artisans in China during the Han dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD) or even earlier.

Han purple and Han blue were synthetic colors made by artisans in China during the Han dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD) or even earlier..jpg.webp) A Japanese woman in a kimono.

A Japanese woman in a kimono. Emperor Komyo of Japan. (1322–1380). Purple was the color of the aristocracy in Japan and China.

Emperor Komyo of Japan. (1322–1380). Purple was the color of the aristocracy in Japan and China.

Medieval Europe

- In medieval Europe, purple represented leadership and the king.[73]

- In European alchemy during this time, "the 'precious purple tincture'" was a term for various substances alchemists hoped to create.[73] The term and goal of the alchemists evoked kingliness,[73] since the divine right of kings was also thought to aid the alchemists' future.

Engineering

The color purple plays a significant role in the traditions of engineering schools across Canada.[79] Purple is also the color of the Engineering Corp in the British Military.[80]

Idioms and expressions

- Purple prose refers to pretentious or overly embellished writing. For example, a paragraph containing an excessive number of long and unusual words is called a purple passage.

- Born to the purple means someone who is born into a life of wealth and privilege. It originally was used to describe the rulers of the Byzantine Empire.

- A purple patch is a period of exceptional success or good luck.[81] The origins are obscure, but it may refer to the symbol of success of the Byzantine Court. Bishops in Byzantium wore a purple patch on their costume as a symbol of rank.

- Purple haze refers to a state of mind induced by psychedelic drugs, particularly LSD.[82]

- Wearing purple is a military slang expression in the U.S., Canada and the U.K. for an officer who is serving in a joint assignment with another service, such as an Army officer on assignment to the Navy. The officer is symbolically putting aside his or her traditional uniform color and exclusive loyalty to their service during the joint assignment, though in fact they continue to wear their own service's uniform.[83]

- Purple squirrel is a term used by employment recruiters to describe a job candidate with precisely the right education, experience, and qualifications that perfectly fits a job's multifaceted requirements. The assumption is that the perfect candidate is as rare as a real-life purple squirrel.

Military

- The Purple Heart is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the President to those who have been wounded or killed during their service.

Politics

- In United States politics, a purple state is a state roughly balanced between Republicans (generally symbolized by red in the 21st century) and Democrats (symbolized by blue).

- In the politics of the Netherlands, Purple (Dutch: paars) means a coalition government consisting of liberals and social democrats (symbolized by the colors blue and red, respectively), as opposed to the more common coalitions of the Christian Democrats with one of the other two. Between 1994 and 2002 there were two Purple cabinets, both led by Prime Minister Wim Kok.

- In the politics of Belgium, as with the Netherlands, a purple government includes liberal and social-democratic parties in coalition. Belgium was governed by Purple governments from 1999 to 2007 under the leadership of Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt.

- Purple is the primary color used by many European and American political parties, including Volt Europa, the UK Independence Party, the Social Democrats in the Republic of Ireland, the Liberal People's Party in Norway, and the United States Pirate Party. The Left party in Germany, whose primary color is red, is traditionally portrayed in purple on election maps to distinguish it from the Social Democratic Party of Germany.

- In the United Kingdom, the color scheme for the suffragette movement in Britain and Ireland was designed with purple for loyalty and dignity, white for purity, and green for hope.[84][85][86]

Rhyme

.jpg.webp)

- In the English language, the word "purple" has only one perfect rhyme, curple. Others are obscure perfect rhymes, such as hirple.

- Robert Burns rhymes purple with curple in his Epistle to Mrs. Scott.

- Examples of imperfect rhymes or non-word rhymes with purple:

- In the song Grace Kelly by Mika the word purple is rhymed with "hurtful".

- In his hit song "Dang Me", Roger Miller sings these lines:

"Roses are red, violets are purple

Sugar is sweet and so is maple surple"

Sexuality

Purple is sometimes associated with the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community. It is the symbolic color worn on Spirit Day, a commemoration that began in 2010 to show support for young people who are bullied because of their sexual orientation.[89][90] Purple is closely associated with bisexuality, largely in part to the bisexual pride flag which combines pink – representing homosexuality – and blue – representing heterosexuality – to create the bisexual purple. The purple hand is another symbol sometimes used by the LGBT community during parades and demonstrations.

Sports and games

- In Motorsport, purple is used to indicate the fastest times of the race.[91]

- The National Basketball Association's Los Angeles Lakers, Phoenix Suns and Sacramento Kings use purple as their primary color.

- In the Indian Premier League, purple is the primary color of the Kolkata Knight Riders.

- In Major League Baseball, purple is one of the primary colors for the Colorado Rockies.

- In the National Football League, the Minnesota Vikings and Baltimore Ravens use purple as main colors.

- The Australian Football League's Fremantle Football Club use purple as one of their primary colors.

- In association football (soccer), Italian Serie A club ACF Fiorentina, Belgian Pro League club and former Europa League winner R.S.C. Anderlecht, French Ligue 1 club Toulouse FC and Ligue 2 club FC Istres, Spanish La Liga club Real Valladolid, Austrian Football Bundesliga club FK Austria Wien, Hungarian Nemzeti Bajnokság I club Újpest FC, Slovenian PrvaLiga club NK Maribor, former Romanian Liga I clubs FC Politehnica Timișoara and FC Argeș Pitești, Andorran Primera Divisió club CE Principat, German club Tennis Borussia Berlin, Italian club A.S.D. Legnano Calcio 1913, Swedish club Fässbergs IF, Japanese club Kyoto Sanga, Australian A-League Club Perth Glory and American Major League Soccer club Orlando City use purple as one of their primary colors.

- The Melbourne Storm from Australia's National Rugby League use purple as one of their primary colors.

- Costa Rica's Primera División soccer team Deportivo Saprissa's main color is purple (actually a burgundy like shade), and their nickname is the "Monstruo Morado", or "Purple Monster".

- In tennis, the official colors of the Wimbledon championships are deep green and purple (traditionally called mauve).

- In American college athletics, Louisiana State University, Kansas State University, Texas Christian University, the University of Central Arkansas, Northwestern University, the University of Washington, and East Carolina University all have purple as one of their main team colors.

- The University of Western Ontario in London, Canada, and Bishop's University in Sherbrooke, Canada, have purple as one of its main team colors.

- Purple is the color of the ball in Snooker Plus with a 10-point value.

- In the game of pool, purple is the color of the 4-solid and the 12-striped balls.

Business

The British chocolate company Cadbury chose purple as it was Queen Victoria's favourite color.[92] The company trademarked the color purple for chocolates with registrations in 1995[93] and 2004.[94] However, the validity of these trademarks is the matter of an ongoing legal dispute following objections by Nestlé.[95]

In flags

- Purple or violet appear in the flags of only two modern sovereign nations, and are merely ancillary colors in both cases. The Flag of Dominica features a sisserou parrot, a national symbol, while the Flag of Nicaragua displays a rainbow in the center, as part of the coat of arms of Nicaragua.

- The lower band of the flag of the second Spanish republic (1931–39) was colored a tone of purple, to represent the common people as opposed to the red of the Spanish monarchy, unlike other nations of Europe where purple represented royalty and red represented the common people.[96]

- In Japan, the prefecture of Tokyo's flag is purple, as is the flag of Ichikawa and other Japanese municipalities.

- Porpora, or purpure, a shade of purple, was added late to the list of colors of European heraldry. A purple lion was the symbol of the old Spanish Kingdom of León (910–1230), and it later appeared on the flag of Spain, when the Kingdom of Castile and Kingdom of León merged.

Flag of Dominica, features a purple sisserou parrot.

Flag of Dominica, features a purple sisserou parrot. Flag of Nicaragua, although at this size the purple band of the rainbow is nearly indistinguishable.

Flag of Nicaragua, although at this size the purple band of the rainbow is nearly indistinguishable..svg.png.webp) Flag of the second Spanish republic (1931–39), known in Spanish as la tricolor, still widely used by left-wing political organizations.

Flag of the second Spanish republic (1931–39), known in Spanish as la tricolor, still widely used by left-wing political organizations.

See also

References

- Dunn, Casey (2013-10-09). "The Color of Royalty, Bestowed by Science and Snails". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- Sadao Hibi; Kunio Fukuda (January 2000). The Colors of Japan. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2536-4.

- Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques

- Iosso, Chris (2019-11-23). "Impeachment and the Perils of Purple Piety: Why You Should Hold a Forum at Your Church". Unbound. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- Heller, Eva: Psychologie de la couleur – effets et symboliques, pp. 179-184

- πορφύρα Archived 2021-03-07 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- "purple, adj. and n." OED Online. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com.

- Anne Varichon, Couleurs-pigments dans les mains des peuples, p. 144–146

- Ball, Philip, Bright Earth; Art and the Invention of Colour. p. 290

- Anne Varichon, Couleurs-pigments dans les mains des peuples, p. 135–138

- Anne Varichon, Couleurs-pigments dans les mains des peuples, p. 135

- KJV Book of Exodus 25:4

- "Biblia Sacra Vulgata". Bible Gateway (in Latin). Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- Anne Varichon (2000), Couleurs: pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples, p. 136

- Liv. xxiv. 7, 2. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

- cf. Cic. post red. in Sen. 5, 12. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

- Zonar. vii. 19. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities

- Liv. xxvii. 8, 8; xxxiii. 42. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities

- cf. Liv. v. 41, 2. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

- "Tyrian Purple in Ancient Rome". Mmdtkw.org. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- Suetonius (121). The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Loeb Classical Library (in Latin and English). Translated by Rolfe, John Carew. Heinemann (published 1914). Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- Annalisa Marzano (1 August 2013). Harvesting the Sea: The Exploitation of Marine Resources in the Roman Mediterranean. OUP Oxford. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-19-967562-3.

- Mark 15:17 and 20

- John Gage (2009), La Couleur dans l'art, p. 148–150.

- Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, p. 163

- Phillip Ball (2001), Bright Earth, Art, and the Invention of Colour, p. 291

- Thieme, C. 2001. (translated by M. Will) Paint Layers and Pigments on the Terracotta Army: A Comparison with Other Cultures of Antiquity. In: W. Yongqi, Z. Tinghao, M. Petzet, E. Emmerling and C. Blänsdorf (eds.) The Polychromy of Antique Sculptures and the Terracotta Army of the First Chinese Emperor: Studies on Materials, Painting Techniques and Conservation. Monuments and Sites III. Paris: ICOMOS, 52–57.

- Liu, Z.; Mehta, A.; Tamura, N.; Pickard, D.; Rong, B.; Zhou, T.; Pianetta, P. (2007). "Influence of Taoism on the invention of the purple pigment used on the Qin terracotta warriors". Journal of Archaeological Science. 34 (11): 1878. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.381.8552. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.01.005. S2CID 17797649.

- "Ancient Warriors and the Origin of Chinese Purple". Stanford University. 30 March 2007.

- FitzHugh, E. W. and Zycherman, L. A. 1983. An Early Man-Made Blue Pigment from China: Barium Copper Silicate. Studies in Conservation 28/1, 15–23.

- "A Lost Purple Pigment, Where Quantum Physics and the Terracotta Warriors Collide". 18 December 2014.

- Varichon, Anne Colors: What They Mean and How to Make Them New York:2006 Abrams Page 140 – This information is in the caption of a color illustration showing an 8th-century manuscript page of the Gospel of Luke written in gold on Tyrian purple parchment.

- Anne Varichon (2000), Couleurs: pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples, p. 137–38

- LaVerne M. Dutton. "Cochineal: A Bright Red Animal Dye" (PDF). Cochineal.info. p. 57. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, p. 165.

- Elena Phipps, Cochineal red: The art history of a color, p. 26.

- Grovier, Kelly. "Tyrian Purple: The disgusting origins of the colour purple". Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- Garfield, S. (2000). Mauve: How One Man Invented a Colour That Changed the World. Faber and Faber, London, UK. ISBN 978-0-571-20197-6.

- Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, image 75–76.

- "Independent Lens . KNOCKING . Jehovah's Witnesses . The Holocaust | PBS". PBS. Archived from the original on 2019-05-30. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques.

- Tager, A.; Kirchner, E.; Fedorovskaya, E. (2021). "Computational evidence of first extensive usage of violet in the 1860s". Color Research & Application. 46 (5): 961–977. doi:10.1002/col.22638. S2CID 233671776.

- St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. p. 159. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- Matschi, M. (2005). "Color terms in English: Onomasiological and Semasiological aspects". Onomasiology Online. 5: 56–139.

- Cooper, A.C.; McLaren, K. (1973). "The ANLAB colour system and the dyer's variables of "shade" and strength". Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists. 89 (2): 41–45. doi:10.1111/j.1478-4408.1973.tb03128.x.

- P. U.P. A Gilbert and Willy Haeberli (2008). Physics in the Arts. Academic Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-12-374150-9.

- See Oxford English Dictionary definition

- Lanier F. (editor) The Rainbow Book Berkeley, California: Shambhala Publications and The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (1976) (Handbook for the Summer 1976 exhibition The Rainbow Art Show which took place primarily at the De Young Museum but also at other museums) Portfolio of color wheels by famous theoreticians—see Rood color wheel (1879) p. 93

- Tager, A.; Kirchner, E.; Fedorovskaya, E. (2021). "Computational evidence of first extensive usage of violet in the 1860s". Color Research & Application. 46 (5): 961–977. doi:10.1002/col.22638. S2CID 233671776.

- Fehrman, K.R.; Fehrman, C. (2004). Color - the secret influence. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

- Matschi, M. (2005). "Color terms in English: Onomasiological and Semasiological aspects". Onomasiology Online. 5: 56–139.

- "violet, n.1". OED Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- "Violet". Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- Georgia State University Department of Physics and Astronomy. "Spectral Colors". HyperPhysics site. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- Charles A. Poynton (2003). Digital video and HDTV. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 1-55860-792-7.

- John Dakin and Robert G. W. Brown (2006). Handbook of Optoelectronics. CRC Press. ISBN 0-7503-0646-7.

- Tom, Scott (18 March 2019). "The Library of Rare Colors". Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 8 May 2019 – via YouTube.

- "Mummy Brown". naturalpigments.com. Archived from the original on 2004-08-16. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- Anne Varichon, Couleurs-pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples, p. 146

- Anne Carichon (2000), Couleurs: pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples. p. 133.

- Isabelle Roelofs, La Couleur Expliquée aux artistes, 52–53.

- St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. p. 211. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- Anne Carichon (2000), Couleurs: pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples. p. 144.

- Hubner K (2006). "History: 150 Years of mauveine". Chemie in unserer Zeit. 40 (4): 274–275. doi:10.1002/ciuz.200690054.

- Anthony S. Travis (1990). "Perkin's Mauve: Ancestor of the Organic Chemical Industry". Technology and Culture. 31 (1): 51–82. doi:10.2307/3105760. JSTOR 3105760.

- D.A. Bryant & N.-U. Frigaard (November 2006). "Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated". Trends Microbiol. 14 (11): 488–96. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001. PMID 16997562.

- "Early Earth Was Purple, Study Suggests". Livescience.com. 2007-04-10. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- Barnett, Lincoln and the editorial staff of Life The World We Live In New York:1955--Simon and Schuster--Page 284 There is also an illustration of Purple Pleione by the noted astronomical artist Chesley Bonestell.

- "Rayleigh scattering Archived 2022-10-31 at the Wayback Machine." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 16 Nov. 2007.

- Mitchinson, Compiled by Molly Oldfield and John (2010-05-21). "QI: Quite Interesting facts about the colour purple". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, p. 162.

- Carlson, Kathie; Flanagin, Michael N.; Martin, Kathleen; Martin, Mary E.; Mendelsohn, John; Rodgers, Priscilla Young; Ronnberg, Ami; Salman, Sherry; Wesley, Deborah A.; et al. (Authors) (2010). Arm, Karen; Ueda, Kako; Thulin, Anne; Langerak, Allison; Kiley, Timothy Gus; Wolff, Mary (eds.). The Book of Symbols: Reflections on Archetypal Images. Köln: Taschen. p. 654. ISBN 978-3-8365-1448-4.

- "Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, p. 167–68

- "Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, p. 170

- "Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, p. 167–174

- "English Funeral and mourning clothing". ox.ac.uk.

- Anne Varichon, Couleurs: pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples, p. 139

- "Purple in culture – HiSoUR – Hi So You Are". Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- "Purple in culture – HiSoUR – Hi So You Are". Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- "purple patch". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021.

- Cottrell, Robert C. (2015). Sex, Drugs, and Rock 'n' Roll: The Rise of America's 1960s Counterculture. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-4422-4607-2.

a confusing drug-induced state

- "Jointness" (PDF). www.carlisle.army.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- "Dress & the Suffragettes". Chertsey Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- Blackman, Cally (8 October 2015). "How the Suffragettes used fashion to further the cause". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- "WSPU Flag". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- "Where fans of Prince music meet and stay up-to-date". Prince.org.

- "Link to the main page of the Princepedia, a Wiki about Prince, on the purple Prince.org Prince fan website". Archived from the original on 2013-01-24. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- "Wear Purple October 20: Spirit Day, Wear Purple Day". longislandpress.com. Archived from the original on 2010-10-22.

- "October 20th is Spirit Day in Hollywood—Neon Tommy's Daily Hollywood". Takepart.com. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- "What do DRS, black and white flag, porpoising and more mean? F1 terms explained". www.autosport.com. Retrieved 2023-03-24.

- "Chocolate wars break out over the colour purple". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- "Trade mark number UK0002020876A" Archived 2022-10-31 at the Wayback Machine. Intellectual Property Office.

- "Intellectual Property Office – By number results". Ipo.gov.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- "Cadbury left black & blue in latest Nestlé battle over the color purple". Confectionerynews.com. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- "Legendary "Purple Banner of Castile" or "Commoner's Banner"". Crwflags.com. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

Further references

- Ball, Philip (2001). Bright Earth, Art and the Invention of Colour. Hazan (French translation). ISBN 978-2-7541-0503-3.

- Heller, Eva (2009). Psychologie de la couleur: Effets et symboliques. Pyramyd (French translation). ISBN 978-2-35017-156-2.

- Pastoureau, Michel (2005). Le petit livre des couleurs. Editions du Panama. ISBN 978-2-7578-0310-3.

- Gage, John (1993). Colour and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction. Thames and Hudson (Page numbers cited from French translation). ISBN 978-2-87811-295-5.

- Gage, John (2006). La Couleur dans l'art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-2-87811-325-9.

- Varichon, Anne (2000). Couleurs: pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples. Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02084697-4.

- Zuffi, Stefano (2012). Color in Art. Abrams. ISBN 978-1-4197-0111-5.

- Roelofs, Isabelle (2012). La couleur expliquée aux artistes. Groupe Eyrolles. ISBN 978-2-212-13486-5.

- "The perception of color", from Schiffman, H.R. (1990). Sensation and perception: An integrated approach (3rd edition). New York: John Wiley & Sons.