Color triangle

A color triangle is an arrangement of colors within a triangle, based on the additive or subtractive combination of three primary colors at its corners.

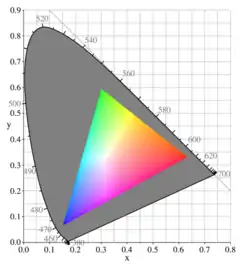

An additive color space defined by three primary colors has a chromaticity gamut that is a color triangle, when the amounts of the primaries are constrained to be nonnegative.[1][2]

Before the theory of additive color was proposed by Thomas Young and further developed by James Clerk Maxwell and Hermann von Helmholtz, triangles were also used to organize colors, for example around a system of red, yellow, and blue primary colors.[3]

After the development of the CIE system, color triangles were used as chromaticity diagrams, including briefly with the trilinear coordinates representing the chromaticity values.[4] Since the sum of the three chromaticity values has a fixed value, it suffices to depict only two of the three values, using Cartesian co-ordinates. In the modern x,y diagram, the large triangle bounded by the imaginary primaries X, Y, and Z has corners (1,0), (0,1), and (0,0), respectively; color triangles with real primaries are often shown within this space.

Maxwell's disc

Maxwell was intrigued by James David Forbes's use of color tops. By rapidly spinning the top, Forbes created the illusion of a single color that was a mixture of the primaries:[5]

[The] experiments of Professor J. D. Forbes, which I witnessed in 1849… [established] that blue and yellow do not make green, but a pinkish tint, when neither prevails in the combination…[and the] result of mixing yellow and blue was, I believe, not previously known.

— James Clerk Maxwell, Experiments on colour, as perceived by the eye, with remarks on colour-blindness (1855), Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

Maxwell took this a step further by using a circular scale around the rim with which to measure the ratios of the primaries, choosing vermilion (V), emerald (EG), and ultramarine (U).[6]

Initially, he compared the color he observed on the spinning top with a paper of different color, in order to find a match. Later, he mounted a pair of papers, snow white (SW) and ivory black (Bk), in an inner circle, thereby creating shades of gray. By adjusting the ratio of primaries, he matched the observed gray of the inner wheel, for example:[7]

To determine the chromaticity of an arbitrary color, he replaced one of the primaries with a sample of the test color and adjusted the ratios until he found a match. For pale chrome (PC) he found . Next, he rearranged the equation to express the test color (PC, in this example) in terms of the primaries.

This would be the precursor to the color matching functions of the CIE 1931 color space, whose chromaticity diagram is shown above.

Drawing of Maxwell's color top

Drawing of Maxwell's color top Maxwell with his wheel

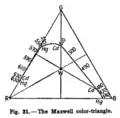

Maxwell with his wheel Maxwell's color triangle

Maxwell's color triangle A color triangle attributed to Fick in 1892, based on imaginary primaries corresponding to the three primary sensations of the human eye. In such a triangle, all real colors fall within the curved outline defined by the "pure sensations".

A color triangle attributed to Fick in 1892, based on imaginary primaries corresponding to the three primary sensations of the human eye. In such a triangle, all real colors fall within the curved outline defined by the "pure sensations".

See also

References

- Arun N. Netravali; G. Haskell (1995). Digital Pictures: Representation, Compression, and Standards (second ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-306-42195-X.

- Werner Backhaus, Reinhold Kliegl and John Simon Werner (1998). Color Vision: Perspectives from Different Disciplines. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-015431-5.

- Sarah Lowengard (2008). The Creation of Color in Eighteenth-Century Europe. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12454-6.

- Judd, Deane B. (January 1935). "A Maxwell Triangle Yielding Uniform Chromaticity Scales". JOSA. 25 (1): 24–35. doi:10.1364/JOSA.25.000024.

- Peter Michael Harman (1998). The Natural Philosophy of James Clerk Maxwell. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00585-X.

- James Clerk Maxwell (2003). The Scientific Papers of James Clerk Maxwell. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-49560-4.

- James Clerk Maxwell (1855), Experiments on colour as perceived by the eye, with remarks on colour-blindness