Caesar's Comet

Caesar's Comet[2] (also Sidus Iulium ("Julian Star"); Caesaris astrum ("Star of Caesar"); Comet Caesar; the Great Comet of 44 BC; numerical designation C/−43 K1) was a seven-day cometary outburst seen in July 44 BC. It was interpreted by Romans as a sign of the deification of recently assassinated dictator, Julius Caesar (100–44 BC).[3] It was perhaps the most famous comet of antiquity.

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Unknown |

| Discovery date | May 18, 44 BC (earliest mention) |

| Designations | |

| Comet Caesar, Sidus lulium "Julian Star", Caesaris astrum "Star of Caesar", C/−43 K1, Great comet of 44 BC | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| Perihelion | 0.22 AU[1] |

| Eccentricity | 1.0 (assumed)[1] |

| Inclination | 110° |

| Last perihelion | May 25, 44 BC[1] |

| Next perihelion | Ejection trajectory assumed |

Based on two sketchy reports from China (May 30) and Rome (July 23), an infinite number of orbit determinations can fit the observations, but a retrograde orbit is inferred based on available notes.[4] The comet approached Earth both inbound in mid-May and outbound in early August.[5] It came to perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) on May 25, −43 at a solar distance of about 0.22 AU (33 million km).[1] At perihelion the comet had a solar elongation of 11 degrees and is hypothesized to have had an apparent magnitude of around −3 as the Chinese report is not consistent with daytime visibility during May.[6] Between June 10 and July 20 the comet would have dimmed from magnitude +1 to around magnitude +5. Around July 20, −43, the comet underwent an estimated 9 magnitude outburst in apparent magnitude[7] and had a solar elongation of 88 degrees in the morning sky. At magnitude −4 it would have been as impressive as Venus.

As a result of the cometary outburst in late July, Caesar's Comet is one of only five comets known to have had a negative absolute magnitude (for a comet, this refers to the apparent magnitude if the comet had been observed at a distance of 1 AU from both the Earth and the Sun[8]) and may have been the brightest daylight comet in recorded history.[9]

In the absence of accurate contemporary observations (or later observations confirming an orbit that predicts the earlier appearance), calculation of the comet's orbit is problematic and a parabolic orbit is conventionally assumed.[1] (In the 1800s a possible match was speculated which would give it a period of about 575 years.[10] This has not been confirmed because the later observations are similarly insufficiently accurate.)[10] The parabolic orbital solution estimates that the comet would now be more than 800 AU (120 billion km) from the Sun.[11] At that distance, the Sun provides less light than the full Moon provides to Earth.

History

Caesar's Comet was known to ancient writers as the Sidus Iulium ("Julian Star") or Caesaris astrum ("Star of Julius Caesar"). The bright, daylight-visible comet appeared suddenly during the festival known as the Ludi Victoriae Caesaris—for which the 44 BC iteration was long considered to have been held in the month of September (a conclusion drawn by Edmund Halley). The dating has recently been revised to a July occurrence in the same year, some four months after the assassination of Julius Caesar, as well as Caesar's own birth month. According to Suetonius, as celebrations were getting underway, "a comet shone for seven successive days, rising about the eleventh hour, and was believed to be the soul of Caesar."[12]

The Comet became a powerful symbol in the political propaganda that launched the career of Caesar's great-nephew (and adoptive son) Augustus. The Temple of Divus Iulius (Temple of the Deified Julius) was built (42 BC) and dedicated (29 BC) by Augustus for purposes of fostering a "cult of the comet". (It was also known as the "Temple of the Comet Star".[13]) At the back of the temple a huge image of Caesar was erected and, according to Ovid, a flaming comet was affixed to its forehead:

To make that soul a star that burns forever

Above the Forum and the gates of Rome.[14]

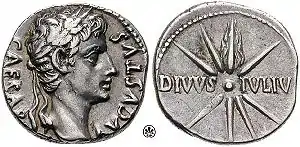

On Roman coinage

Tracing the coinage from 44 BC through the developing rule of Augustus reveals the changing relationship of Julius Caesar to the Sidus Iulium. Robert Gurval notes that the shifting status of Caesar's Comet in the coinage follows a definite pattern. Representations of the deified Julius Caesar as a star appeared relatively quickly, occurring within several years of his death. About twenty years passed, however, before the star completed its transformation into a comet.[15] Starting in 44 BC, a money maker named P. Sepullius Macer created coins with the front displaying Julius Caesar crowned with a wreath and a star behind his head. On the back, Venus, the patron goddess of the Julian family, holds a starred scepter. Gurval maintains that this coin was minted about the time of Caesar's assassination and thus probably would not have originally referred to his deification. As it circulated, however, it would have brought that idea to mind because of Caesar's new cult.[15] Kenneth Scott's older work The Sidus Iulium and the Apotheosis of Caesar contests this by assuming that the comet did indeed spark this series because of similarity to other coins he produced.[16] A series of Roman aurei and denarii minted after this cult began show Mark Antony and a star, which most likely represents his position as Caesar's priest.[15] In later coins likely originating near the end of Octavian's war with Sextus Pompey, the star supplants Caesar's name and face entirely, clearly representing his divinity.[15]

One of the clearest and earliest correlations of Caesar to a comet occurred during the Secular Games of 17 BC when money maker M. Sanquinius fashioned coins whose reverse sports a comet over the head of a wreathed man whom classicists and numismatists speculate is either a youthful Caesar, the Genius of the Secular Games, the Julian family, or Aeneas' son Iulus. These coins strengthened the link between Julius Caesar and Augustus since Augustus associated himself with the Julians. Another set of Spanish coins displays an eight-rayed comet with the words DIVVS IVLIVS,[15] meaning Divine Julius.

In literature

The poet Virgil writes in his ninth eclogue that the star of Caesar has appeared to gladden the fields.[17] Virgil later writes of the period following Julius Caesar's assassination, "Never did fearsome comets so often blaze."[18] Gurval points out that this passage in no way links a comet to Caesar's divine status, but rather links comets to his death.[15]

Calpurnius Siculus makes mention of the comet in his epilogues as a boding sign of the civil strife that would plague Rome after Caesar's death.[19]

It is Ovid, however, who makes the final assertion of the comet's role in Julius Caesar's deification. Ovid describes the deification of Caesar in Metamorphoses (8 AD):

Then Jupiter, the Father, spoke..."Take up Caesar's spirit from his murdered corpse, and change it into a star, so that the deified Julius may always look down from his high temple on our Capitol and forum." He had barely finished, when gentle Venus stood in the midst of the Senate, seen by no one, and took up the newly freed spirit of her Caesar from his body, and preventing it from vanishing into the air, carried it towards the glorious stars. As she carried it, she felt it glow and take fire, and loosed it from her breast: it climbed higher than the moon, and drawing behind it a fiery tail, shone as a star.[20]

It has been argued recently that the idea of Augustus's use of the comet for his political aims largely stems from this passage.[21]

In Shakespeare's Julius Caesar (1599), Caesar's wife remarks on the fateful morning of her husband's murder: "When beggars die there are no comets seen. The heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes."

Modern scholarship

In 1997, two scholars at the University of Illinois at Chicago—John T. Ramsey (a classicist) and A. Lewis Licht (a physicist)—published a book[22] comparing astronomical/astrological evidence from both Han China and Rome. Their analysis, based on historical eyewitness accounts, Chinese astronomical records, astrological literature from later antiquity and ice cores from Greenland glaciers, yielded a range of orbital parameters for the hypothetical object. They settled on a perihelion point of 0.22 AU for the object which was apparently visible with a tail from the Chinese capital Chang'an (in late May) and as a star-like object from Rome (in late July):

Robert Gurval of UCLA and Brian G. Marsden of the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics leave the comet's very existence as an open question. Marsden notes in his foreword to Ramsey and Licht's book, "Given the circumstance of a single reporter two decades after the event, I should be remiss if I were not to consider this [i.e., the comet's non-existence] as a serious possibility."[24]

See also

References

- "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: C/−43 K1" (arc: 54 days). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- Ramsey, J.T.; A. Lewis Licht (1997). The comet of 44 B.C. and Caesar's funeral games. American classical studies. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press. ISBN 0788502735.

- Grant, Michael (1970), The Roman Forum, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson; Photos by Werner Forman, p. 94.

- The Comet of 44 B.C. and Caesar's Funeral Games (John T. Ramsey, A. Lewis Licht) p. 125

- Cometography Vol 1 p. 22 by Gary W. Kronk

- See Ramsey pp. 122–23: (Comet absolute magnitude H1 of 3.3) + 2.5 * (n of 4) * log (Sun distance of 0.220 AU) + 5 * log (Earth distance of 1.09 AU) = perihelion apparent magnitude of −3.1.

- The Comet of 44 B.C. and Caesar's Funeral Games (John T. Ramsey, A. Lewis Licht) p. 123

- Hughes, David W (1990). "Cometary absolute magnitudes, their significance and distribution". Asteroids: 327. Bibcode:1990acm..proc..327H.

- Flare-up on July 23–25, 44 BC (Rome): −4.0 (Richter model) and −9.0 (41P/Tuttle-Giacobini-Kresák model); absolute magnitude on May 26, 44 BC (China): −3.3 (Richter) and −4.4 (41P/TGK); calculated in Ramsey and Licht, Op. cit., p. 236.

- François Arago (1832). Tract On Comets. Translated by John Farrar. Hilliard, Gray. p. 71.

- "Horizon Online Ephemeris System". California Institute of Technology, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- Suetonius, Divus Julius; 88 The Twelve Caesars

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 2.93–94.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses; XV, 840.

- Gurval, Robert A. (1997). "Caesar's comet: The politics and poetics of an Augustan myth". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. 42: 39–71. doi:10.2307/4238747. ISSN 0065-6801. JSTOR 4238747.

- Scott, Kenneth (July 1941). "The Sidus Iulium and the Apotheosis of Caesar". Classical Philology. 36 (3): 257–272. doi:10.1086/362515. ISSN 0009-837X. JSTOR 265276. S2CID 162367121.

- Williams, Mary Frances (2003). "The Sidus Iulium, the divinity of men, and the Golden Age in Virgil's Aeneid" (PDF). Leeds International Classical Studies. 2 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-11. Retrieved 2014-03-23.

- Georgic 1.487–488 qtd. In Ramsey and Licht, Op. cit

- Siculus, Titus Calpurnius; Scott, Edward John Long (1890). "The Eclogues of Calpurnius".

- Ovid, Metamorphoses; XV; 745–842.

- Pandey, Nandini B. (2013). "Caesar's Comet, the Julian Star, and the Invention of Augustus". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 143 (2): 405–449. doi:10.1353/apa.2013.0010. ISSN 1533-0699. S2CID 153697502. Retrieved 2014-03-22.

- Ramsey and Licht, Op. cit.

- The Comet of 44 B.C. and Caesar's Funeral Games (John T. Ramsey, A. Lewis Licht) pg 121

- Marsden, Brian G., "Forward"; In: Ramsey and Licht, Op. cit.

.png.webp)