Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic

The Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) was one of two supreme commanders of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), the other being the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). The SACLANT led Allied Command Atlantic was based at Norfolk, Virginia. The entire command was routinely referred to as 'SACLANT'.

| Allied Command Atlantic | |

|---|---|

ACLANT Emblem. | |

| Active | 30 January 1952 – 19 June 2003 |

| Country | NATO |

| Size | Command |

| Headquarters | Norfolk, Virginia |

| Nickname(s) | SACLANT |

| Engagements | Cold War |

In 1981 SACLANT's wartime task was listed as being to provide for the security of the area by guarding sea lanes to deny their use to an enemy and to safeguard them for the reinforcement and resupply of NATO Europe with personnel and materiel.[1]

The command's area of responsibility extended from the North Pole to the Tropic of Cancer as well as extending from the east coast of North America to the west coast of Africa and Europe, including Portugal but not the English Channel, the British Isles, and the Canary Islands.[2]

History

Soon after its formation, ACLANT together with Allied Command Europe carried out the large exercise Exercise Mainbrace. Throughout the Cold War years, SACLANT carried out many other exercises, such as Operation Mariner in 1953 and Operation Strikeback in 1957, as well as the Northern Wedding and Ocean Safari series of naval exercises during the 1970s and 1980s. The command also played a critical role in the annual Exercise REFORGER from the 1970s onwards. Following the end of the Cold War, the Command was reduced in status and size, with many of its subordinate headquarters spread across the Atlantic area losing their NATO status and funding. However, the basic structure remained in place until the Prague Summit in the Czech Republic in 2002.

Carrier-based air strike operations in the Norwegian Sea pioneered by Operation Strikeback foreshadowed planning such as the NATO Concept of Maritime Operations of 1980 (CONMAROPS).[3] The purpose of the Atlantic lifelines campaign was to protect the transportation of allied reinforcement and resupply across the Atlantic, practiced via Exercise Ocean Safari. The shallow-seas campaign was designed to prevent the exit of the Soviet Baltic Fleet into the North Sea and to protect allied convoys in the North Sea and the English Channel; it was exercised in Exercise Northern Wedding series. The Norwegian Sea campaign was meant to prevent the exit of the Soviet Northern Fleet into the Norwegian Sea and the Atlantic Ocean and to provide sea-based support to allied air and ground operations in Norway. Its associated series of exercises was Exercise Teamwork. The U.S. Maritime Strategy promulgated in the mid 1980s dovetailed with the CONMAROPS and went further in some cases, such as in the operation of Carrier Battle Groups far forward, in Norwegian coastal waters sheltered by the mountains surrounding the northern Norwegian fjords.

In January 1968, the Standing Naval Force Atlantic (STANAVFORLANT) was established.[4] This was a permanent peacetime multinational naval squadron composed of various NATO navies' destroyers, cruisers and frigates. Since 1967, STANAVFORLANT operated, trained, and exercised as a group. It also participated in NATO and national naval exercises designed to promote readiness and interoperability.[5]

The Maritime Strategy was published in 1984, championed by Secretary of the Navy John Lehman and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral James D. Watkins, USN, during the Reagan Administration, and practiced in NATO naval exercises such as Ocean Safari '85 and Northern Wedding '86.[6][7][8][9]

In a 2008 article, retired General Bernard E. Trainor, USMC, noted the success of this maritime strategy:

By going on the immediate offensive in the high north and putting the Soviets on the defensive in their home waters, the Maritime Strategy not only served to defend Scandinavia, but also served to mitigate the SLOC problem. The likelihood of timely reinforcement of NATO from the United States was now more than a pious hope.

With the emergence of an offensive strategy in the 1980s, a change in mindset was energized by concurrent dramatic advances in American technology, especially in C4ISR and weapon systems, that were rapidly offsetting Soviet numerical and material superiority in Europe. No lesser light than the USSR Chief of the General Staff, Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov warned that American superiority was shifting the "correlation of forces" in NATO's favor. He called the phenomenon a "military technological revolution." By the end of the decade the military threat from the Soviet Union was consigned to the dust bin of history and with it, the Cold War.[10][11]

The U.S. Navy's Forward Maritime Strategy provided the strategic rationale for the "600-ship Navy".[12][13]

Allied Command Atlantic was redesignated as Allied Command Transformation (ACT) on 19 June 2003. ACT was to be headed by the Supreme Allied Commander Transformation (SACT), up to 2009 an American four-star admiral or general who was dual-hatted as commander, United States Joint Forces Command (COMUSJFCOM). SACLANT's former military missions were folded into NATO's Allied Command Operations (ACO).[14]

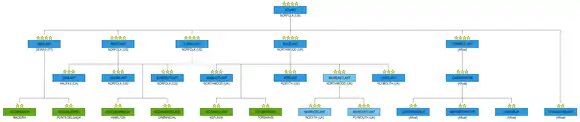

Structure

The high command of ACLANT comprised the following positions:

- Supreme Allied Commander (SACLANT) – SACLANT was responsible for all Alliance military missions within the ACLANT area of responsibility. SACLANT was a United States admiral who also serves as the Commander-in-Chief U.S. Atlantic Command, one of the Department of Defense unified combatant commands. After the end of the Cold War, Army generals began to be assigned to the position.

- Deputy Supreme Allied Commander (DSACLANT) – The principal deputy to SACLANT held by a British vice-admiral. DSACLANT was originally the commander of the Royal Navy's North America and West Indies Station.

- Chief of Staff (COFS) – Directs the SACLANT headquarters staff

SACLANT headquarters was located in Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia, adjacent to the U.S. Atlantic Fleet headquarters.[15]

Eastern Atlantic Area (EASTLANT)

%252C_ca._1954.gif)

Commander-in-Chief, Eastern Atlantic Area (CINCEASTLANT) was a British admiral based at the Northwood Headquarters in northwest London, who also served as Commander in Chief, Home Fleet (subsequently CINC Western Fleet, and later Commander-in-Chief Fleet).[16] In 1953 his primary task was described as the 'integrated defence and the control and protection of sea and air lines of communications within' the Eastern Atlantic Area. On 12 December 1952, an EASTLANT integrated submarine headquarters was established. Rear Admiral G.W.G. Simpson, CB, CBE, RN, Flag Officer Submarines, was appointed Commander Submarine Force Eastern Atlantic (COMSUBEASTLANT) and assumed his command with its headquarters at Gosport, Hants, in the United Kingdom.[17]

On 2 February 1953, the planning staff of CINCEASTLANT, which had been temporarily established at Portsmouth, England, moved into interim facilities adjacent to the established Headquarters of CINCAIREASTLANT at Northwood, England. This, SACLANT wrote, would greatly facilitate the effective exercise of command in the Eastern Atlantic Area.

In 1953, initial NATO documents instructing Admiral George Creasy wrote that the following Sub-Area commanders had been appointed within EASTLANT:[18]

- Commander Bay of Biscay Sub-Area: Vice Admiral A. Robert, French Navy

- Commander North-East Atlantic Sub-Area: Vice Admiral Sir Maurice Mansergh, KCB, CBE, Royal Navy (UK national appointment of Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth)

- Air Commander North Sea: Air Vice Marshal Harold Lydford, CB, CBE, Royal Air Force (AOC No. 18 Group RAF)

- Air Commander North-East Atlantic Sub-Area : Air Vice Marshal Thomas Traill, CB, OBE, DFC, Royal Air Force (AOC No. 19 Group RAF)

- Commander Northern European Sub-Area : Rear Admiral J.H.F. Crombie, CB, DSO, Royal Navy (Flag Officer Scotland and Northern Ireland, Pitreavie Castle, Scotland)

Circa 1962, Central Sub-Area was led by the Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth, and Northern Sub-Area by Flag Officer Scotland and Northern Ireland.[19]

After 1966, CINCEASTLANT was responsible for the administration and operation of the Standing Naval Force Atlantic, on behalf of SACLANT. In 1982, EASTLANT was organised as follows:[20]

- Eastern Atlantic Area (EASTLANT)

- Northern Sub-Area (NORLANT)

- Central Sub-Area (CENTLANT)

- Submarine Force Eastern Atlantic (SUBEASTLANT)

- Maritime Air Eastern Atlantic (AIREASTLANT)

- Maritime Air Northern Sub-Area (AIRNORLANT)

- Maritime Air Central Sub-Area (AIRCENTLANT)

- Island Commander Iceland (ISCOMICE)

- Island Commander Faeroes (ISCOMFAROES)

Western Atlantic Area

Commander-in-Chief Western Atlantic (CINCWESTLANT) was an American Admiral based at Naval Station Norfolk, Norfolk, Virginia who also served as the Commander-in-Chief U.S. Atlantic Fleet.[21]

In 1953, sub-area commanders were listed as follows:

- Commander United States Atlantic Sub-Area, Vice Admiral Oscar Badger, U.S. Navy (seemingly Commander, Eastern Sea Frontier)

- Commander Canadian Atlantic Sub-Area, Rear Admiral R.E.S. Bidwell, CBS, CD, Royal Canadian Navy (Commander, Canadian Coastal Defence Atlantic)

- Air Commander Canadian Atlantic Sub-Area, Air Commodore A.D. Ross, GC, CBE, CD, Royal Canadian Air Force

In 1981, the Western Atlantic Area included six subordinate headquarters:[1]

- Submarine Force Western Atlantic Area

- Ocean Sub-Area

- Canadian Atlantic Sub-Area

- Island Commander Bermuda

- Island Commander Azores[22] Lajes Field, in the Portuguese islands of the Azores, was an important transatlantic staging post.

- Island Commander Greenland

In the last few years of the post, CINCWESTLANT was responsible for:

- The safe transit of critical reinforcement and re-supply from North America to Europe, in support of the full spectrum of NATO forces operating anywhere in or beyond NATO's area of responsibility

- The sponsorship of peacetime joint multinational exercises and Partnership for Peace (PfP) activities, as well as maintaining operational control and providing support for NATO forces assigned to the headquarters

From 1994 through 2003, WESTLANT was organized as follows:[23]

- SubWestLant

- Ocean Sub-Area

- Canadian Atlantic Sub-Area

- Greenland Island Commander

Iberian Atlantic Area

In 1950, the command structure and organization of Allied Command Atlantic (ACLANT) was approved except that the North Atlantic Ocean Regional Group was requested to reconsider the command arrangements for the Iberian Atlantic Area (IBERLANT).[24] IBERLANT was an integral part of this ACLANT command structure. In MC 58(Revised) (Final), it was stated that the question of subdividing IBERLANT was still under study. However, because arrangement regarding the establishment of IBERLANT, could not be agreed, CINCEASTLANT and CINCAIREASTLANT were assigned, as an interim emergency measure, the temporary responsibility for the IBERLANT area. NATO exercises, however, demonstrated that these interim arrangements proved unsatisfactory.

Commander Iberian Atlantic Area was eventually established in 1967 as a Principal Subordinate Commander (PSC), reporting to CINCWESTLANT. The commander was a U.S. Navy rear admiral who also served as chief of the Military Assistance and Advisory Group in Lisbon.[25] In 1975 IBERLANT was described as 'probably of greater symbolic value to Portugal than of military value to NATO' in internal cables of the U.S. Department of State.[26] In 1981 the command included the Island Command Madeira.[1] In 1982 NATO agreed to the upgrading of IBERLANT into a Major Subordinate Command (MSC), becoming Commander-in-Chief Iberian Atlantic Area (CINCIBERLANT). A Portuguese Navy Vice Admiral, dual-hatted as the fleet commander, took over the position. It was planned that Commander, Portuguese Air (COMPOAIR), a sub-PSC, would eventually take responsibility for the air defence of Portugal, reporting through CINCIBERLANT to SACEUR. Thus the Portuguese mainland would be 'associated' with Allied Command Europe.

In 1999 CINCIBERLANT became Commander-in-Chief Southern Atlantic (CINCSOUTHLANT). He was made responsible for military movements and maritime operations across the southeast boundary between Allied Command Europe and Allied Command Atlantic.[27] The command became Allied Joint Force Command Lisbon before being deactivated in 2012.

Striking Fleet Atlantic

Commander Striking Fleet Atlantic (COMSTRIKFLTLANT) was SACLANT's major subordinate seagoing commander. The primary mission of Striking Fleet Atlantic was to deter aggression by maintaining maritime superiority in the Atlantic AOR and ensuring the integrity of NATO's sea lines of communications. The Striking Fleet's Commander was a U.S. Navy Vice Admiral based at Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia who also served as the Commander U.S. Second Fleet.[20][28] In 1981 the American Forces Information Service listed its components as the Carrier Striking Force consisting of Carrier Striking Groups One and Two.[1] The Carrier Striking Force appears to have been Task Force 401. The Carrier Striking Force appears to have had an American nucleus, built around Carrier Group Four, and Carrier Striking Group Two appears to have had a British nucleus, later, it seems, becoming Anti-Submarine Group Two.[29] When HMS Ark Royal took part in Exercise Royal Knight circa 1972, she formed the centrepiece of Striking Group Two and led Task Group 401.2.[30]

When Vice Admiral Hank Mustin became COMSTRIKFLTLANT he reorganised the Fleet by adding amphibious and landing force (seemingly UK/NL Amphibious Force[31]) components. In 1998, Commander Striking Fleet Atlantic directed three Principal Subordinate Commanders and three Sub-Principal Subordinate Commanders:[32]

- Commander Carrier Striking Force (also U.S. Navy Commander Carrier Strike Group 4)

- Commander Anti-Submarine Warfare Striking Force (also Royal Navy Commander UK Task Group; previously held in the 1980s by Flag Officer, Third Flotilla)

- Commander Amphibious Striking Force (also U.S. Navy Commander Amphibious Group 2)

The three Sub-PSCs were:

- Commander Marine Striking Force (also USMC Commanding General, II Marine Expeditionary Force)

- Commander UK/NL Amphibious Force (also Royal Navy Commodore, Amphibious Task Group)

- Commander UK/NL Landing Force (also Royal Marine Brigadier, Commander 3 Commando Brigade)

STRIKFLTLANT was deactivated in a ceremony held on USS Iwo Jima (LHD-7) on June 24, 2005, being replaced by the Combined Joint Operations from the Sea Center of Excellence located at the Second Fleet headquarters.[33]

Submarine Allied Command Atlantic (SUBACLANT)

The Commander Submarine Allied Command Atlantic (COMSUBACLANT) was the principal adviser to the SACLANT on submarine matters and undersea warfare. COMSUBACLANT was an American three-star admiral based in Norfolk, Virginia, who also served as the Commander Submarine Force Atlantic Fleet (COMSUBLANT).[34] Under SUBACLANT were Commander, Submarines, Western Atlantic Area (COMSUBWESTLANT) and Commander, Submarines, Eastern Atlantic Area (COMSUBEASTLANT). COMSUBEASTLANT's national appointment was the Royal Navy post of Flag Officer Submarines.[35] Flag Officer Submarines moved in 1978 from HMS Dolphin at Gosport to the Northwood Headquarters in northwest London.

Structure in 1989

- Allied Command Atlantic (ACLANT), led by Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT), in Norfolk, United States[36][37]

- Commander-in-Chief, Eastern Atlantic Area (EASTLANT), in Northwood, United Kingdom

- Northern Sub-Area (NORLANT), in Rosyth, United Kingdom

- Central Sub-Area (CENTLANT), in Plymouth, United Kingdom

- Submarine Force Eastern Atlantic (SUBEASTLANT), in Northwood, United Kingdom

- Maritime Air Eastern Atlantic (MAIREASTLANT), in Northwood, United Kingdom

- Maritime Air Northern Sub-Area (MAIRNORLANT), Pitreavie Castle, United Kingdom

- Maritime Air Central Sub-Area (MAIRCENTLANT), in Plymouth, United Kingdom

- Island Command Iceland (ISCOMICELAND), in Keflavík, Iceland

- Island Command Faroes (ISCOMFAROES), in Tórshavn, Faroe Islands

- Commander-in-Chief, Western Atlantic Area (WESTLANT), in Norfolk, United States

- Ocean Sub-Area (OCEANLANT), in Norfolk, United States

- Canadian Atlantic Sub-Area (CANLANT), in Halifax, Canada

- Island Command Bermuda (ISCOMBERMUDA), in Hamilton, Bermuda

- Island Command Greenland (ISCOMGREENLAND), in Grønnedal, Greenland

- Submarine Force Western Atlantic (SUBWESTLANT), in Norfolk, United States

- Iberian Atlantic Area (IBERLANT), in Lisbon, Portugal

- Island Command Madeira (ISCOMADEIRA), in Funchal, Madeira

- Island Command Azores (ISCOMAZORES), in Ponta Delgada, Azores, transferred from WESTLANT to IBERLANT in 1989

- Striking Fleet Atlantic (STRIKFLTLANT), afloat

- Carrier Striking Force (CARSTRIKFOR), afloat

- Carrier Striking Group (CARSTRIKGRU), afloat

- Amphibious Force (AMPHIBSTRIKFOR), afloat

- Anti-Submarine Warfare Group, afloat

- Carrier Striking Force (CARSTRIKFOR), afloat

- Submarines Allied Command Atlantic (SUBACLANT), in Norfolk, United States

- Standing Naval Force Atlantic (STANAVFORLANT), afloat

- Commander-in-Chief, Eastern Atlantic Area (EASTLANT), in Northwood, United Kingdom

The organisation of Striking Fleet Atlantic shifted over time. Initially Carrier Striking Groups One (US) and Two (RN) were subordinate to the Striking Fleet, as depicted in NATO Facts and Figures, 1989.[36] When the last Royal Navy fixed-wing carriers were retired in the late 1970s Carrier Striking Group Two became the Anti-Submarine Warfare Striking Force. NATO Facts and Figures 1989 misses the removal of Carrier Striking Group Two which had occurred around ten years earlier.

Commanders

List of Supreme Allied Commanders Atlantic

| Date | Incumbent | Service | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 Jan 1952 – 12 Apr 1954 | ADM Lynde D. McCormick | USN |

| 2 | 12 Apr 1954 – 29 Feb 1960 | ADM Jerauld Wright | USN |

| 3 | 29 Feb 1960 – 30 Apr 1963 | ADM Robert L. Dennison | USN |

| 4 | 30 Apr 1963 – 30 Apr 1965 | ADM Harold Page Smith | USN |

| 5 | 30 Apr 1965 – 17 Jun 1967 | ADM Thomas H. Moorer | USN |

| 6 | 17 Jun 1967 – 30 Sep 1970 | ADM Ephraim P. Holmes | USN |

| 7 | 30 Sep 1970 – 31 Oct 1972 | ADM Charles K. Duncan | USN |

| 8 | 31 Oct 1972 – 30 May 1975 | ADM Ralph W. Cousins | USN |

| 9 | 30 May 1975 – 30 Sep 1978 | ADM Isaac C. Kidd Jr. | USN |

| 10 | 30 Sep 1978 – 30 Sep 1982 | ADM Harry D. Train II | USN |

| 11 | 30 Sep 1982 – 27 Nov 1985 | ADM Wesley L. McDonald | USN |

| 12 | 27 Nov 1985 – 22 Nov 1988 | ADM Lee Baggett Jr. | USN |

| 13 | 22 Nov 1988 – 18 May 1990 | ADM Frank B. Kelso II | USN |

| 14 | 18 May 1990 – 13 Jul 1992 | ADM Leon A. Edney | USN |

| 15 | 13 Jul 1992 – 31 Oct 1994 | ADM Paul David Miller | USN |

| 16 | 31 Oct 1994 – 24 Sep 1997 | GEN John J. Sheehan | USMC |

| 17 | 24 Sep 1997 – 05 Sep 2000 | ADM Harold W. Gehman Jr. | USN |

| 18 | 05 Sep 2000 – 02 Oct 2002 | GEN William F. Kernan | USA |

| (Acting) | Oct 2002 – 19 June 2003 | Adm Sir Ian Forbes[38] | RN |

List of Deputy Supreme Allied Commanders Atlantic

His Second-in-Command was the Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic:[39]

| Date | Incumbent | Service | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1952–1953 | Vice Admiral Sir William Andrewes | RN |

| 2 | 1953–1955 | Vice Admiral Sir John Stevens | RN |

| 3 | 1955–1956 | Vice Admiral Sir John Eaton | RN |

| 4 | 1957–1960 | Vice Admiral Sir Wilfrid Woods | RN |

| 5 | 1960–1962 | Vice Admiral Sir Charles Evans | RN |

| 6 | 1962–1964 | Vice Admiral Sir Richard Smeeton | RN |

| 7 | 1964–1966 | Vice Admiral Sir William Beloe | RN |

| 8 | 1966–1968 | Vice Admiral Sir David Clutterbuck | RN |

| 9 | 1968–1970 | Vice Admiral Sir Peter Compston | RN |

| 10 | 1970–1973 | Vice Admiral Sir John Martin | RN |

| 11 | 1973–1975 | Vice Admiral Sir Gerard Mansfield | RN |

| 12 | 1975–1977 | Vice Admiral Sir James Jungius | RN |

| 13 | 1977–1980 | Vice Admiral Sir David Loram | RN |

| 14 | 1980–1982 | Vice Admiral Sir Cameron Rusby | RN |

| 15 | 1983–1984 | Vice Admiral Sir David Hallifax | RN |

| 16 | 1984–1987 | Vice Admiral Sir Geoffrey Dalton | RN |

| 17 | 1987–1989 | Vice Admiral Sir Richard Thomas | RN |

| 18 | 1989–1991 | Vice Admiral Sir James Weatherall | RN |

| 19 | 1991–1993 | Vice Admiral Sir Peter Woodhead | RN |

| 20 | 1993–1995 | Vice Admiral Sir Peter Abbott | RN |

| 21 | 1995–1998 | Vice Admiral Sir Ian Garnett | RN |

| 22 | 1998–2002 | Vice Admiral Sir James Perowne | RN |

| 23 | Jan – Oct 2002 | Vice Admiral Sir Ian Forbes | RN |

References

- American Forces Information Service (1981). NAVMC2727, A Pocket guide to NATO. DA pam360-419. Washington, D.C.?: Department of Defense. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- "Allied Command Atlantic". NATO Handbook. Archived from the original on August 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- Commodore Jacob BØRRESEN RNN, 'Alliance Naval Strategies and Norway in the Final Years of the Cold War Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Naval War College Review, Spring 2011, 99–100.

- Hattendorf, John B. (Summer 2008). "Admiral Richard G. Colbert: Pioneer in Building Global Maritime Partnerships". Naval War College Review. 61 (3): 109–131. ISSN 0028-1484. JSTOR 26396946.

- NATO Office of Information and Press (2001). NATO Handbook (1. Aufl ed.). Brussels: NATO. p. 266. ISBN 978-92-845-0146-5. Archived from the original on August 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- Trainor, Bernard E. (March 23, 1987). "Lehman's Sea-War Strategy Is Alive, but for How Long?". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- "Ocean Safari '85: Meeting the Threat in the North Atlantic" (PDF). All Hands (826): 20–29. January 1986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-11-16. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- Connors, Tracy (January 1987). "Northern Wedding '86" (PDF). All Hands (838): 18–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-11-16. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- Tangen, Odd F. (1989). "The Situation In The Norwegian Sea Today". CSC. Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- Trainor, Bernard E. (February 2008). "Triumph in Strategic Thinking". Naval Institute Proceedings. 134 (2). p. 42.

- For a brief overview on the Soviet concept of correlation of forces, see Major Richard E. Porter, USAF. "Correlation of Forces: Revolutionary Legacy" Archived 2014-04-27 at the Wayback Machine Air University Review, March–April 1977

- Allen, Thad; Conway, James T.; Roughead, Gary (November 2007). "A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower". Naval Institute Proceedings. 133 (11): 14–20. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- Lehman, John (November 2007). "A Bravura Performance". Naval Institute Proceedings. 133 (11): 22–24. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- "New NATO Transformation Command Established in Norfolk". American Forces Press Service. United States Department of Defense. 19 June 2003. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- Key Jr., David M. (2001). Admiral Jerauld Wright: Warrior among Diplomats. Manhattan, Kansas: Sunflower University Press. pp. 299–304. ISBN 978-0-89745-251-9.

- "Regional Headquarters, Eastern Atlantic". NATO Handbook. Archived from the original on August 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- "PERIODIC REPORT BY THE SUPREME ALLIED COMMANDER, ATLANTIC ( NO. 4 - 14 OCTOBER 1952-09 APRIL 1953) - NATO Archives Online". Archived from the original on 2015-02-22.

- Standing Group Memoranda (1953-08-11). "THE NATO MILITARY COMMAND STRUCTURE". NATO Archives Online.

- A. Cecil Hampshire, "The Royal Navy Since 1945," 1975, p206.

- Source: IISS Military Balance 1981–82, p.26

- "Regional Headquarters, Western Atlantic". NATO Handbook. Archived from the original on 2008-09-11. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- A Portuguese Navy rear admiral. Library of Congress Country Study: Portugal: Navy, January 1993, accessed 21 June 2008

- NATO's Sixteen Nations, Special Issue, 1998, p.15

- SGWM-033-59, NATO Archives.

- Young, Command in NATO after the Cold War, 171-2.

- "Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume E–15, Part 2, Documents on Western Europe, 1973–1976 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- "Regional Headquarters, Southern Atlantic". NATO Handbook. Archived from the original on September 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- "Striking Fleet Atlantic". NATO Handbook. Archived from the original on September 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- See List of fleets and major commands of the Royal Navy, Flag Officer Third Flotilla, and Proceedings, August 2001, 'Commanding NATO operations from the sea'

- Rowland White, Phoenix Squadron, Bantam Press, 2009, 99.

- Huitfeldt, Tønne; Diesen, Sverre; Tamnes, Rolf; Dalhaug, Arne B.; Gjelsten, Roald (1990). Soviet 'reasonable sufficiency' and Norwegian security (Report). Forsvarsstudier;5. Institutt for Forsvarsstudier.

- NATO's Sixteen Nations, Special Issue 1998.

- "NATO Striking Fleet Atlantic to Deactivate". Commander, U.S. 2nd Fleet Public Affairs. U.S. Navy. June 23, 2005. Archived from the original on November 22, 2006. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- "Submarine Allied Command Atlantic". NATO Handbook. Archived from the original on September 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- UK MOD, Northwood Headquarters

- Gregory, S. (18 December 1995). Nuclear Command and Control in NATO: Nuclear Weapons Operations and the Strategy of Flexible Response. Springer. ISBN 9780230379107.

- NATO: Fact and Figures (PDF) (11th ed.). Brussels: NATO. 1989. p. 348.

- "Nato Review". Archived from the original on 2012-09-25. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- "Senior Royal Navy appointments" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2012.

- Air Force Association (May 2006). "USAF Almanac 2006" (PDF). Air Force Magazine. 89 (5). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2007.

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization. "Senior officials in the NATO military structure, from 1949 to 2001" (PDF).

- Young, Thomas-Durrell (June 1, 1997). "Command in NATO After the Cold War: Alliance, National, and Multinational Considerations]". Carlisle, PA: U.S. Army Strategic Studies Institute.

Further reading

- Atlantic Council of the United States (August 2003). "Transforming the NATO Military Command Structure: A New Framework for Managing the Alliance's Future" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-03.

- Maloney, Sean M. Securing Command of the Sea: NATO Naval Planning, 1948–1954. Naval Institute Press, 1995. 276 pp.

- Jane's NATO Handbook Edited by Bruce George, 1990, Jane's Information Group ISBN 0-7106-0598-6

- Jane's NATO Handbook Edited by Bruce George, 1991, Jane's Information Group ISBN 0-7106-0976-0