Commercial paper

Commercial paper, in the global financial market, is an unsecured promissory note with a fixed maturity of rarely more than 270 days. In layperson terms, it is like an "IOU" but can be bought and sold because its buyers and sellers have some degree of confidence that it can be successfully redeemed later for cash, based on their assessment of the creditworthiness of the issuing company.

| Part of a series on |

| Financial markets |

|---|

|

| Bond market |

| Stock market |

| Other markets |

| Over-the-counter (off-exchange) |

| Trading |

| Related areas |

Commercial paper is a money-market security issued by large corporations to obtain funds to meet short-term debt obligations (for example, payroll) and is backed only by an issuing bank or company promise to pay the face amount on the maturity date specified on the note. Since it is not backed by collateral, only firms with excellent credit ratings from a recognized credit rating agency will be able to sell their commercial paper at a reasonable price. Commercial paper is usually sold at a discount from face value and generally carries lower interest repayment rates than bonds due to the shorter maturities of commercial paper. Typically, the longer the maturity on a note, the higher the interest rate the issuing institution pays. Interest rates fluctuate with market conditions but are typically lower than banks' rates.

Commercial paper, though a short-term obligation, is typically issued as part of a continuous rolling program, which is either a number of years long (in Europe) or open-ended (in the United States).[1]

Overview

As defined in United States law, commercial paper matures before nine months (270 days), and is only used to fund operating expenses or current assets (e.g., inventories and receivables) and not used for financing fixed assets, such as land, buildings, or machinery.[2] By meeting these qualifications it may be issued without U.S. federal government regulation, that is, it need not be registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.[3] Commercial paper is a type of negotiable instrument, where the legal rights and obligations of involved parties are governed by Articles Three and Four of the Uniform Commercial Code, a set of laws adopted by 49 of the 50 states, Louisiana being the exception.[4]

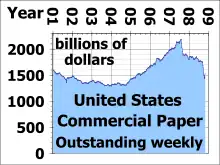

At the end of 2009, more than 1,700 companies in the United States issued commercial paper. As of October 31, 2008, the U.S. Federal Reserve reported seasonally adjusted figures for the end of 2007: there was $1.7807 trillion in total outstanding commercial paper; $801.3 billion was "asset backed" and $979.4 billion was not; $162.7 billion of the latter was issued by non-financial corporations, and $816.7 billion was issued by financial corporations.[5]

Outside of the United States the international Euro-Commercial Paper Market has over $500 billion in outstandings, made up of instruments denominated predominantly in euros, dollars and sterling.[6]

History

Commercial credit (trade credit), in the form of promissory notes issued by corporations, has existed since at least the 19th century. For instance, Marcus Goldman, founder of Goldman Sachs, got his start trading commercial paper in New York in 1869.[7][8]

Issuance

Commercial paper – though a short-term obligation – is issued as part of a continuous significantly longer rolling program, which is either a number of years long (as in Europe), or open-ended (as in the U.S.).[1][9] Because the continuous commercial paper program is much longer than the individual commercial paper in the program (which cannot be longer than 270 days), as commercial paper matures it is replaced with newly issued commercial paper for the remaining amount of the obligation.[10] If the maturity is less than 270 days, the issuer does not have to file a registrations statement with the SEC, which would mean delay and increased cost.[11]

There are two methods of issuing credit. The issuer can market the securities directly to a buy and hold investor such as most money market funds. Alternatively, it can sell the paper to a dealer, who then sells the paper in the market. The dealer market for commercial paper involves large securities firms and subsidiaries of bank holding companies. Most of these firms also are dealers in US Treasury securities. Direct issuers of commercial paper usually are financial companies that have frequent and sizable borrowing needs and find it more economical to sell paper without the use of an intermediary. In the United States, direct issuers save a dealer fee of approximately 5 basis points, or 0.05% annualized, which translates to $50,000 on every $100 million outstanding. This saving compensates for the cost of maintaining a permanent sales staff to market the paper. Dealer fees tend to be lower outside the United States.

Line of credit

Commercial paper is a lower-cost alternative to a line of credit with a bank. Once a business becomes established, and builds a high credit rating, it is often cheaper to draw on a commercial paper than on a bank line of credit. Nevertheless, many companies still maintain bank lines of credit as a "backup". Banks often charge fees for the amount of the line of the credit that does not have a balance, because under the capital regulatory regimes set out by the Basel Accords, banks must anticipate that such unused lines of credit will be drawn upon if a company gets into financial distress. They must therefore put aside equity capital to account for potential loan losses also on the currently unused part of lines of credit, and will usually charge a fee for the cost of this equity capital.

Advantages of commercial paper:

- High credit ratings fetch a lower cost of capital.

- Wide range of maturity provide more flexibility.

- It does not create any lien on asset of the company.

- Tradability of Commercial Paper provides investors with exit options.

Disadvantages of commercial paper:

- Its usage is limited to only blue chip companies.

- Issuances of commercial paper bring down the bank credit limits.

- A high degree of control is exercised on issue of Commercial Paper.

- Stand-by credit may become necessary

Commercial paper yields

Like treasury bills, yields on commercial paper are quoted on a discount basis—the discount return to commercial paper holders is the annualized percentage difference between the price paid for the paper and the face value using a 360-day year. Specifically, where is the discount yield, is the face value, is the price paid, and is the term length of the paper in days:

and when converted to a bond equivalent yield ():

Defaults

In case of default, the issuer of commercial paper (large corporate) would be debarred for 6 months and credit ratings would be dropped down from existing to "Default".

Defaults on high quality commercial paper are rare, and cause concern when they occur.[13] Notable examples include:

- On June 21, 1970, Penn Central filed for bankruptcy under Chapter 7 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code and defaulted on approximately $77.1 million of commercial paper. This sparked a runoff in the commercial paper market of approximately $3 billion, causing the Federal Reserve to intervene by permitting commercial banks to borrow at the discount window.[14] This placed a substantial burden on clients of the issuing dealer for Penn Central’s commercial paper, Goldman Sachs.[15]

- On January 31, 1997, Mercury Finance, a major automotive lender, defaulted on a debt of $17 million, rising to $315 million. Effects were small, partly because default occurred during a robust economy.[13]

- On September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers caused two money funds to break the buck, and led to Fed intervention in money market funds.

References

- Coyle, Brian (2002). Corporate Bonds and Commercial Paper. ISBN 9780852974568. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- Hahn, Thomas K.; Cook, Timothy Q.; Laroche, Robert K. (1993). "Commercial Paper," Ch. 9, in Instruments of the Money Market (PDF). Richmond, VA: Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. pp. 106–07.

- 15 U.S.C. Section 77c(a)(3)

- Ontario Securities Commission National Instrument 45-106 (Section 2.35) Accessed 2007-01-30

- Federal Reserve. "FRB: Commercial Paper Outstanding". Retrieved October 31, 2008.

Data as of October 29, 2008

- "Bonds Money Market Outstanding - Collaborative Market Data Network - CMDportal".

- "Uhtermyer Urges Money Bill Changes; Approves Measure, but Wants Commercial Paper Defined in Its Strict Meaning". The New York Times. September 23, 1913. p. 9.

- "Commercial Paper Should Be Changed; Gardin Thinks Three Years Sufficient for Transition to European Practice". The New York Times. March 1, 1914.

- Moorad Choudhry (December 14, 2011). Corporate Bond Markets: Instruments and Applications. ISBN 9781118178997. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- Frank, Barney (September 2009). Recent Events in the Credit and Mortgage Markets and Possible Implications ... ISBN 9781437914948. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- Frank J. Fabozzi, CFA; Pamela Peterson Drake; Ralph S. Polimeni (2008). The Complete CFO Handbook: From Accounting to Accountability. John Wiley & Sons. p. 89. ISBN 9780470099261. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

commercial paper program rolling.

- "Commercial Paper".

- Stojanovic, Dusan; Vaughan, Mark D. "The Commercial Paper Market: Who's Minding the Shop?". Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, The Financial Collapse of the Penn Central Company, Staff Report of the Securities and Exchange Commission to the Special Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington DC 1972, page 272.

- Ellis, Charles D. The Partnership: The Making of Goldman Sachs. Rev. ed. London: Penguin, 2009. 98. Print.

External links

- "Commercial Paper Rates and Outstanding Summary". Federal Reserve System. May 5, 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- Kennedy, Siobhan (August 22, 2007). "Banks get new battering as commercial paper is caught up in crisis". The Times. London. Retrieved June 1, 2017. An article on commercial paper and credit market vernacular.

- Hahn, Thomas K. (Spring 1993). "Commercial Paper" (PDF). Economic Quarterly. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, VA. Retrieved June 1, 2017. History of origin, and special regulations governing the issuing of commercial paper.

- Davidson, Adam; Blumberg, Alex (September 26, 2008). "The Week America's Economy Almost Died". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Retrieved June 1, 2017.