Swap (finance)

In finance, a swap is an agreement between two counterparties to exchange financial instruments, cashflows, or payments for a certain time. The instruments can be almost anything but most swaps involve cash based on a notional principal amount.[1][2]

| Part of a series on |

| Financial markets |

|---|

|

| Bond market |

| Stock market |

| Other markets |

| Over-the-counter (off-exchange) |

| Trading |

| Related areas |

The general swap can also be seen as a series of forward contracts through which two parties exchange financial instruments, resulting in a common series of exchange dates and two streams of instruments, the legs of the swap. The legs can be almost anything but usually one leg involves cash flows based on a notional principal amount that both parties agree to. This principal usually does not change hands during or at the end of the swap; this is contrary to a future, a forward or an option.[3]

In practice one leg is generally fixed while the other is variable, that is determined by an uncertain variable such as a benchmark interest rate, a foreign exchange rate, an index price, or a commodity price.[4]

Swaps are primarily over-the-counter contracts between companies or financial institutions. Retail investors do not generally engage in swaps.[5]

Example

A mortgage holder is paying a floating interest rate on their mortgage but expects this rate to go up in the future. Another mortgage holder is paying a fixed rate but expects rates to fall in the future. They enter a fixed-for-floating swap agreement. Both mortgage holders agree on a notional principal amount and maturity date and agree to take on each other's payment obligations. The first mortgage holder from now on is paying a fixed rate to the second mortgage holder while receiving a floating rate. By using a swap, both parties effectively changed their mortgage terms to their preferred interest mode while neither party had to renegotiate terms with their mortgage lenders.

Considering the next payment only, both parties might as well have entered a fixed-for-floating forward contract. For the payment after that another forward contract whose terms are the same, i.e. same notional amount and fixed-for-floating, and so on. The swap contract therefore, can be seen as a series of forward contracts. In the end there are two streams of cash flows, one from the party who is always paying a fixed interest on the notional amount, the fixed leg of the swap, the other from the party who agreed to pay the floating rate, the floating leg.

Swaps can be used to hedge certain risks such as interest rate risk, or to speculate on changes in the expected direction of underlying prices.[6]

History

Swaps were first introduced to the public in 1981 when IBM and the World Bank entered into a swap agreement.[7] Today, swaps are among the most heavily traded financial contracts in the world: the total amount of interest rates and currency swaps outstanding was more than $348 trillion in 2010, according to Bank for International Settlements (BIS).[8]

Most swaps are traded over-the-counter(OTC), "tailor-made" for the counterparties. The Dodd-Frank Act in 2010, however, envisions a multilateral platform for swap quoting, the swaps execution facility (SEF),[9] and mandates that swaps be reported to and cleared through exchanges or clearing houses which subsequently led to the formation of swap data repositories (SDRs), a central facility for swap data reporting and recordkeeping.[10] Data vendors, such as Bloomberg,[11] and big exchanges, such as the Chicago Mercantile Exchange,[12] the largest U.S. futures market, and the Chicago Board Options Exchange, registered to become SDRs. They started to list some types of swaps, swaptions and swap futures on their platforms. Other exchanges followed, such as the IntercontinentalExchange and Frankfurt-based Eurex AG.[13]

According to the 2018 SEF Market Share Statistics[14] Bloomberg dominates the credit rate market with 80% share, TP dominates the FX dealer to dealer market (46% share), Reuters dominates the FX dealer to client market (50% share), Tradeweb is strongest in the vanilla interest rate market (38% share), TP the biggest platform in the basis swap market (53% share), BGC dominates both the swaption and XCS markets, Tradition is the biggest platform for Caps and Floors (55% share).

Size of market

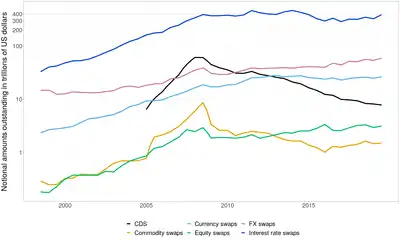

While the market for currency swaps developed first, the interest rate swap market has surpassed it, measured by notional principal, "a reference amount of principal for determining interest payments."[15]

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) publishes statistics on the notional amounts outstanding in the OTC derivatives market. At the end of 2006, this was USD 415.2 trillion, more than 8.5 times the 2006 gross world product. However, since the cash flow generated by a swap is equal to an interest rate times that notional amount, the cash flow generated from swaps is a substantial fraction of but much less than the gross world product—which is also a cash-flow measure. The majority of this (USD 292.0 trillion) was due to interest rate swaps. These split by currency as:

| Currency | Notional outstanding (in USD trillion) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End 2000 | End 2001 | End 2002 | End 2003 | End 2004 | End 2005 | End 2006 | |

| Euro | 16.6 | 20.9 | 31.5 | 44.7 | 59.3 | 81.4 | 112.1 |

| US dollar | 13.0 | 18.9 | 23.7 | 33.4 | 44.8 | 74.4 | 97.6 |

| Japanese yen | 11.1 | 10.1 | 12.8 | 17.4 | 21.5 | 25.6 | 38.0 |

| Pound sterling | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.2 | 7.9 | 11.6 | 15.1 | 22.3 |

| Swiss franc | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 3.5 |

| Total | 48.8 | 58.9 | 79.2 | 111.2 | 147.4 | 212.0 | 292.0 |

Major Swap Participant

A Major Swap Participant (MSP, or sometimes Swap Bank) is a generic term to describe a financial institution that facilitates swaps between counterparties. It maintains a substantial position in swaps for any of the major swap categories. A swap bank can be an international commercial bank, an investment bank, a merchant bank, or an independent operator. A swap bank serves as either a swap broker or swap dealer. As a broker, the swap bank matches counterparties but does not assume any risk of the swap. The swap broker receives a commission for this service. Today, most swap banks serve as dealers or market makers. As a market maker, a swap bank is willing to accept either side of a currency swap, and then later on-sell it, or match it with a counterparty. In this capacity, the swap bank assumes a position in the swap and therefore assumes some risks. The dealer capacity is obviously more risky, and the swap bank would receive a portion of the cash flows passed through it to compensate it for bearing this risk.[1][16]

Swap market efficiency

The two primary reasons for a counterparty to use a currency swap are to obtain debt financing in the swapped currency at an interest cost reduction brought about through comparative advantages each counterparty has in its national capital market, and/or the benefit of hedging long-run exchange rate exposure. These reasons seem straightforward and difficult to argue with, especially to the extent that name recognition is truly important in raising funds in the international bond market. Firms using currency swaps have statistically higher levels of long-term foreign-denominated debt than firms that use no currency derivatives.[17] Conversely, the primary users of currency swaps are non-financial, global firms with long-term foreign-currency financing needs.[18] From a foreign investor's perspective, valuation of foreign-currency debt would exclude the exposure effect that a domestic investor would see for such debt. Financing foreign-currency debt using domestic currency and a currency swap is therefore superior to financing directly with foreign-currency debt.[18]

The two primary reasons for swapping interest rates are to better match maturities of assets and liabilities and/or to obtain a cost savings via the quality spread differential (QSD). Empirical evidence suggests that the spread between AAA-rated commercial paper (floating) and A-rated commercial is slightly less than the spread between AAA-rated five-year obligation (fixed) and an A-rated obligation of the same tenor. These findings suggest that firms with lower (higher) credit ratings are more likely to pay fixed (floating) in swaps, and fixed-rate payers would use more short-term debt and have shorter debt maturity than floating-rate payers. In particular, the A-rated firm would borrow using commercial paper at a spread over the AAA rate and enter into a (short-term) fixed-for-floating swap as payer.[19]

Types of swaps

The generic types of swaps, in order of their quantitative importance, are: interest rate swaps, basis swaps, currency swaps, inflation swaps, credit default swaps, commodity swaps and equity swaps. There are also many other types of swaps.

Interest rate swaps

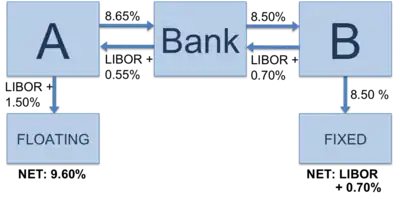

The most common type of swap is an interest rate swap. Some companies may have comparative advantage in fixed rate markets, while other companies have a comparative advantage in floating rate markets. When companies want to borrow, they look for cheap borrowing, i.e. from the market where they have comparative advantage. However, this may lead to a company borrowing fixed when it wants floating or borrowing floating when it wants fixed. This is where a swap comes in. A swap has the effect of transforming a fixed rate loan into a floating rate loan or vice versa.

For example, party B makes periodic interest payments to party A based on a variable interest rate of LIBOR +70 basis points. Party A in return makes periodic interest payments based on a fixed rate of 8.65%. The payments are calculated over the notional amount. The first rate is called variable because it is reset at the beginning of each interest calculation period to the then current reference rate, such as LIBOR. In reality, the actual rate received by A and B is slightly lower due to a bank taking a spread.

Basis swaps

A basis swap involves exchanging floating interest rates based on different money markets. The principal is not exchanged. The swap effectively limits the interest-rate risk as a result of having differing lending and borrowing rates.[20]

Currency swaps

A currency swap involves exchanging principal and fixed rate interest payments on a loan in one currency for principal and fixed rate interest payments on an equal loan in another currency. Just like interest rate swaps, the currency swaps are also motivated by comparative advantage. Currency swaps entail swapping both principal and interest between the parties, with the cashflows in one direction being in a different currency than those in the opposite direction. It is also a very crucial uniform pattern in individuals and customers.

Inflation swaps

An inflation-linked swap involves exchanging a fixed rate on a principal for an inflation index expressed in monetary terms. The primary objective is to hedge against inflation and interest-rate risk.[21]

Commodity swaps

A commodity swap is an agreement whereby a floating (or market or spot) price is exchanged for a fixed price over a specified period. The vast majority of commodity swaps involve crude oil.

Credit default swap

An agreement whereby the payer periodically pays premiums, sometimes also or only a one-off or initial premium, to the protection seller on a notional principal for a period of time so long as a specified credit event has not occurred.[22] The credit event can refer to a single asset or a basket of assets, usually debt obligations. In the event of default, the payer receives compensation, for example the principal, possibly plus all fixed rate payments until the end of the swap agreement, or any other way that suits the protection buyer or both counterparties. The primary objective of a CDS is to transfer one party's credit exposure to another party.

Subordinated risk swaps

A subordinated risk swap (SRS), or equity risk swap, is a contract in which the buyer (or equity holder) pays a premium to the seller (or silent holder) for the option to transfer certain risks. These can include any form of equity, management or legal risk of the underlying (for example a company). Through execution the equity holder can (for example) transfer shares, management responsibilities or else. Thus, general and special entrepreneurial risks can be managed, assigned or prematurely hedged. Those instruments are traded over-the-counter (OTC) and there are only a few specialized investors worldwide.

Equity swap

An agreement to exchange future cash flows between two parties where one leg is an equity-based cash flow such as the performance of a stock asset, a basket of stocks or a stock index. The other leg is typically a fixed-income cash flow such as a benchmark interest rate.

Other variations

There are myriad different variations on the vanilla swap structure, which are limited only by the imagination of financial engineers and the desire of corporate treasurers and fund managers for exotic structures.[4]

- A total return swap is a swap in which party A pays the total return of an asset, and party B makes periodic interest payments. The total return is the capital gain or loss, plus any interest or dividend payments. Note that if the total return is negative, then party A receives this amount from party B. The parties have exposure to the return of the underlying stock or index, without having to hold the underlying assets. The profit or loss of party B is the same for him as actually owning the underlying asset.[22]

- An option on a swap is called a swaption. These provide one party with the right but not the obligation at a future time to enter into a swap.[22]

- A variance swap is an over-the-counter instrument that allows investors to trade future realized (or historical) volatility against current implied volatility.[23]

- A constant maturity swap (CMS) is a swap that allows the purchaser to fix the duration of received flows on a swap.

- An amortizing swap is usually an interest rate swap in which the notional principal for the interest payments declines during the life of the swap, perhaps at a rate tied to the prepayment of a mortgage or to an interest rate benchmark such as the LIBOR. It is suitable to those customers of banks who want to manage the interest rate risk involved in predicted funding requirement, or investment programs.[22]

- A zero coupon swap is of use to those entities which have their liabilities denominated in floating rates but at the same time would like to conserve cash for operational purposes.

- A deferred rate swap is particularly attractive to those users of funds that need funds immediately but do not consider the current rates of interest very attractive and feel that the rates may fall in future.

- An accreting swap is used by banks which have agreed to lend increasing sums over time to its customers so that they may fund projects.

- A forward swap is an agreement created through the synthesis of two swaps differing in duration for the purpose of fulfilling the specific time-frame needs of an investor. Also referred to as a forward start swap, delayed start swap, and a deferred start swap.

- A quanto swap is a cash-settled, cross-currency interest rate swap in which one counterparty pays a foreign interest rate to the other, but the notional amount is in domestic currency. The second party may be paying a fixed or floating rate. For example, a swap in which the notional amount is denominated in Canadian dollars, but where the floating rate is set as USD LIBOR, would be considered a quanto swap. Quanto swaps are known as differential or rate-differential or diff swaps.

- A range accrual swap (or range accrual note) is an agreement to pay a fixed or floating rate while receiving cash flows from a fixed or floating rate which are accrued only on those days where the second rate falls within a preagreed range. The received payments are maximized when the second rate stays entirely within the range for the duration of the swap.

- A three-zone digital swap is a generalization of the range accrual swap, the payer of a fixed rate receives a floating rate if that rate stays within a certain preagreed range, or a fixed rate if the floating rate goes above the range, or a different fixed rate if the floating rate falls below the range.

Valuation and Pricing

The value of a swap is the net present value (NPV) of all expected future cash flows, essentially the difference in leg values. A swap is thus "worth zero" when it is first initiated, otherwise one party would be at an advantage, and arbitrage would be possible; however after this time its value may become positive or negative.[4]

While this principle holds true for any swap, the following discussion is for plain vanilla interest rate swaps and is representative of pure rational pricing as it excludes credit risk. For interest rate swaps, there are in fact two methods, which will (must) return the same value: in terms of bond prices, or as a portfolio of forward contracts.[4] The fact that these methods agree, underscores the fact that rational pricing will apply between instruments also.

Arbitrage arguments

As mentioned, to be arbitrage free, the terms of a swap contract are such that, initially, the NPV of these future cash flows is equal to zero. Where this is not the case, arbitrage would be possible.

For example, consider a plain vanilla fixed-to-floating interest rate swap where Party A pays a fixed rate, and Party B pays a floating rate. In such an agreement the fixed rate would be such that the present value of future fixed rate payments by Party A are equal to the present value of the expected future floating rate payments (i.e. the NPV is zero). Where this is not the case, an Arbitrageur, C, could:

- assume the position with the lower present value of payments, and borrow funds equal to this present value

- meet the cash flow obligations on the position by using the borrowed funds, and receive the corresponding payments - which have a higher present value

- use the received payments to repay the debt on the borrowed funds

- pocket the difference - where the difference between the present value of the loan and the present value of the inflows is the arbitrage profit.

Subsequently, once traded, the price of the Swap must equate to the price of the various corresponding instruments as mentioned above. Where this is not true, an arbitrageur could similarly short sell the overpriced instrument, and use the proceeds to purchase the correctly priced instrument, pocket the difference, and then use payments generated to service the instrument which he is short.

Using bond prices

While principal payments are not exchanged in an interest rate swap, assuming that these are received and paid at the end of the swap does not change its value. Thus, from the point of view of the floating-rate payer, a swap is equivalent to a long position in a fixed-rate bond (i.e. receiving fixed interest payments), and a short position in a floating rate note (i.e. making floating interest payments):

From the point of view of the fixed-rate payer, the swap can be viewed as having the opposite positions. That is,

Similarly, currency swaps can be regarded as having positions in bonds whose cash flows correspond to those in the swap. Thus, the home currency value is:

- , where is the domestic cash flows of the swap, is the foreign cash flows of the LIBOR is the rate of interest offered by banks on deposit from other banks in the eurocurrency market. One-month LIBOR is the rate offered for 1-month deposits, 3-month LIBOR for three months deposits, etc.

LIBOR rates are determined by trading between banks and change continuously as economic conditions change. Just like the prime rate of interest quoted in the domestic market, LIBOR is a reference rate of interest in the international market.

See also

- auction

- Category:Swaps (finance), for a list of articles

- Constant maturity swap

- Credit default swap

- Cross currency swap

- Equity swap

- Foreign exchange swap

- Fuel price risk management

- Interest rate swap

- Multi-curve framework

- PnL Explained

- Swap Execution Facility

- Total return swap

- Variance swap

- Yield curve

References

- Saunders, A.; Cornett, M. (2006). Financial Institutions Management. McGraw-Hill Irwin.

- Financial Industry Business Ontology Version 2 Archived 2020-07-02 at the Wayback Machine, Annex D: Derivatives, EDM Council, Inc., Object Management Group, Inc., 2019

- "What is a swap?". Investopedia. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- Finance: A Quantitative Introduction by Piotr Staszkiewicz and Lucia Staszkiewicz; Academic Press 2014, pg. 56.

- John C Hull, Options, Futures and Other Derivatives (6th edition), New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2006, 149

- "SEC Charges International Dealer That Sold Security-Based Swaps to U.S. Investors". Archived from the original on 2019-12-08. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- "Understanding Derivatives: Markets and Infrastructure - Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago". chicagofed.org. Archived from the original on 12 August 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- Ross; Westerfield & Jordan (2010). Fundamentals of Corporate Finance (9th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 746.

- "OTC derivatives statistics at end-June 2017". www.bis.org. 2017-11-02. Archived from the original on 2018-07-16. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

- "Swaps Execution Facilities (SEFs)". U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "Data Repositories". U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "Bloomberg Launches Its Swap Data Repository". Bloomberg L.p. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "CME Swap Data Repository". Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- "Exchange for Swaps". Eurex Exchange. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Khwaja, Amir (9 January 2019). "2018 SEF Market Share Statistics". ClarusFT. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT, THIRD EDITION, PART TWO, Chapter 10: "Currency and Interest Rate Swaps", by Eun Resnick; The McGraw−Hill Companies, 2004". Archived from the original on 2019-10-24. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- "Intermediaries". U.S. Commodities Futures Trading Commission. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Geczy, C.; Minton, B.; Schrand, C. (1997). "Why firms use currency derivatives". Journal of Finance. 52 (4): 1323–1354. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb01112.x. Archived from the original on 2021-09-28. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- Goswami, G.; Nam, J.; Shrikhande, M. (2004). "Why do global firms use currency swaps?: Theory and evidence". Journal of Multinational Financial Management. 14 (4–5): 315–334. doi:10.1016/j.mulfin.2004.03.003.

- Li, H.; Mao, C. (2003). "Corporate use of interest rate swaps: Theory and evidence". Journal of Banking & Finance. 27 (8): 1511–1538. doi:10.1016/S0378-4266(02)00275-3.

- "Financial Industry Business Ontology" Version 2 Archived 2020-07-02 at the Wayback Machine, Annex D: Derivatives, EDM Council, Inc., Object Management Group, Inc., 2019

- "How Liquid Is the Inflation Swap Market?" Archived 2019-12-05 at the Wayback Machine Michael J. Fleming and John Sporn, 2013

- Frank J. Fabozzi, 2018. The Handbook of Financial Instruments, Wiley ISBN 978-1-119-52296-6

- "Introduction to Variance Swaps" Archived 2019-12-08 at the Wayback Machine, Sebastien Bossu, Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein, Wilmott Magazine, 16 April 2018

External links

- Understanding Derivatives: Markets and Infrastructure Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Financial Markets Group

- Investment-foundations: Derivatives Archived 2020-10-27 at the Wayback Machine, CFA Institute

- swaps-rates.com, interest swap rates statistics online

- Bank for International Settlements

- International Swaps and Derivatives Association

- First take, Dodd-Frank's SEC’s Cross-Border Derivatives Rule