Comparison of Lao and Thai

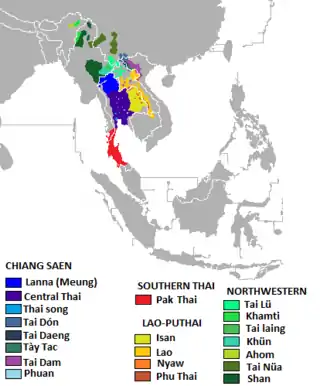

Lao and Thai are two closely related languages of the Southwestern branch of Tai languages. Lao falls within the Lao-Phuthai group of Southwestern Tai languages and Thai within the Chiang Saen language group. Lao (including Isan) and Thai, although they occupy separate groups, are mutually intelligible and were pushed closer through contact and Khmer influence, but all Southwestern Tai languages are mutually intelligible to some degree.[1] Isan refers to the local development of the Lao language in Thailand, as it diverged in isolation from Laos, under Thai influence. The Isan language is still referred to as Lao by native speakers.[2] Spoken Lao is mutually intelligible with Thai and Isan to such a degree that their speakers are able to effectively communicate with one another speaking their respective languages. These languages are written with slightly different scripts, the Lao script and Thai script, but are linguistically similar and effectively form a dialect continuum.[3]

Although Thai and Lao (including Isan) are mutually intelligible, Thai speakers without previous exposure to the Isan language encounter several difficulties parsing the spoken language. Isan, written according to Thai etymological spelling, is fairly legible to Thai as the two languages share more than eighty percent cognate vocabulary, similar to the relationship between Spanish and Portuguese as changes in the meanings of terms, retention of archaisms, slightly different grammar and some vocabulary differences blur the close relationship.[4] The relationship is asymmetric, with Isan speakers able to understand spoken and written Thai quite well due to its mandatory use in school and the popularity of Thai media and participation in Thai society, but many Isan students suffer the shock of switching from the Isan language of the home to the Central Thai-only primary school.[5]

False friends

Many Lao terms are very similar to words that are profane, vulgar or insulting in the Thai language, features that are much deprecated. Lao uses ອີ່ (/ʔīː/ and ອ້າຍ/archaic ອ້າຽ (/ʔâːj/), to refer to young girls and slightly older boys, respectively. In Thai, the similarly sounding อี, i (/ʔiː/) and ไอ้, ai (/ʔâj) are often prefixed before a woman's or man's name, respectively, or alone or in phrases that are considered extremely vulgar and insulting. These taboo expressions such as อีตัว "i tua", "whore" (/ʔiː nɔːŋ/) and ไอ้บ้า, "ai ba", "son of a bitch" (/ʔâj baː/).

| Isan | Lao | IPA | Usage | Thai | IPA | Usage |

| บัก, bak | ບັກ, bak | /bák/ | Used alone or prefixed before a man's name, only used when addressing a man of equal or lower socio-economic status and/or age. | บัก, bak | /bàk/ | Alone, refers to a "penis" or in the expression บักโกรก, bak khrok, or an unflattering way to refer to someone as "skinny". |

| หำน้อย, ham noy | ຫຳນ້ອຍ/archaic ຫຳນ້ຽ, ham noy | /hăm nɔ̑ːj/ | Although ham has the meaning of "testicles", the phrase bak ham noy is used to refer to a small boy. Bak ham by itself is used to refer to a "young man". | หำน้อย, ham noy | /hăm nɔ´ːj/ | This would sound similar to saying "small testicles" in Thai, and would be a rather crude expression. Bak ham is instead ชายหนุ่ม, chai num (/tɕʰaːj nùm/) and bak ham noy is instead เด็กหนุ่ม, dek num (/dèk nùm/) when referring to "young man" and "young boy", respectively, in Thai. |

| หมู่, mu | ໝູ່, mou | /mūː/ | Mu is used to refer to a group of things or people, such as ໝູ່ເຮົາ/ຫມູ່ເຮົາ, mou hao (/mūː háo/), or "all of us" or "we all". Not to be confused for ໝູ/ຫມູ mou (/mŭː/), pig. | พวก, phuak | /pʰǔak/ | The Isan word หมู่ sounds like the Thai word หมู (/mŭː/), 'pig', in most varieties of Isan. To refer to groups of people, the equivalent expression is พวก, phuak (/pʰǔak/), i.e., พวกเรา, phuak rao (/pʰǔak rào/) for "we all" or "all of us". Use of mu to indicate a group would make the phrase sound like "we pigs". |

| ควาย, khway | ຄວາຍ/archaic ຄວາຽ, khouay | /kʰúaːj/ | Isan vowel combinations with the semi-vowel "ວ" are shorted, so would sounds more like it were written as ควย. | ควาย, khway | /kʰwaːj/ | Khway as pronounced in Isan is similar to the Thai word ควย, khuay (/kʰúaj/), which is another vulgar, slang word for "penis". |

Phonological differences

Thai and Lao share a similar phonology, being closely related languages, however, several developments occurred in Lao that clearly distinguish them. Tone, including patterns and quality, is the largest contributing factor and varies widely between varieties of Lao, but together they share splits quite distinct to Standard Thai and other Central Thai speech varieties. There are also several key sound changes that occurred in the Lao language that differentiates it from Thai.

Consonantal differences

Lao lacks the /r/ of formal Thai, replacing it with /h/ or /l/, as well as /t͡ɕʰ/, which is replaced by /s/. Lao also has the consonant sounds /ɲ/ and /ʋ/, which are absent in Thai. Aside from these differences, the consonantal inventory is mostly shared between the two languages.

C1C2 > C1

Unlike Thai, the only consonant clusters that traditionally occur is C/w/, limited in Lao to /kw/ and /kʰw/ but only in certain environments as the /w/ is assimilated into a diphthongization process before the vowels /aː/, /am/, /aːj/ and /a/ thus limiting their occurrence. For example, Isan kwang (กว้าง, ກວ້າງ kouang, /kûːəŋ/) is pronounced *kuang (*กว้ง, *ກວ້ງ) but kwaen as in kwaen ban (แกว้นบ้าน, ແກວ່ນບ້ານ khoèn ban, /kwɛ̄ːn bȃːn/), 'to feel at home', has a vowel that does not trigger the diphthongization. The consonant clusters of Proto-Tai had mostly merged in Proto-Southwestern Tai, but clusters were re-introduced with Khmer, Sanskrit, Pali and European loan words, particularly C/l/ and C/r/. Lao simplified the clusters to the first element, but sporadically maintained its orthographic representation as late as the early twentieth century although their pronunciation was simplified much earlier. This was likely an influence of Thai.[6]

In some instances, some loan words are sometimes pronounced with clusters by very erudite speakers in formal contexts or in the speech of Isan youth that is very Thaified, otherwise the simplified pronunciation is more common. Lao speakers, especially erudite speakers may write and pronounce prôkram (ໂປຣກຣາມ, /proːkraːm/), via French programme (/pʁɔgʁam/), and maitri (ໄມຕຣີ, /máj triː/) from Sanskrit maitri (मैत्री, /maj triː/) are common, more often than not, they exist as pôkam (ໂປກາມ, /poːkaːm/) and maiti (ໄມຕີ, /máj tiː/), respectively. Similarly, Isan speakers always write and sometimes pronounce, in 'Thai fashion', maitri (ไมตรี, /máj triː/) and prokraem (โปรแกรม, /proː krɛːm/), via English 'programme' or 'program' (US), but most speakers reduce it to máj tiː/ and /poː kɛːm/, respectively, in normal speech.

| Thai | Isan | Lao | Thai | Isan | Lao | Thai | Isan | Lao | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ก | /k/ | ก | /k/ | ກ | /k/ | ค | /kʰ/ | ค | /kʰ/ | ຄ | /kʰ/ | ผ | /pʰ/ | ผ | /pʰ/ | ຜ | /pʰ/ |

| กร | /kr/ | กร | คร | /kʰr/ | คร | ผล | /pʰl/ | ผล | |||||||||

| กล | /kl/ | กล | คล | /kʰl/ | คล | พ | /pʰ/ | พ | /pʰ/ | ພ | /pʰ/ | ||||||

| ข | /kʰ/ | ข | /kʰ/ | ຂ | /kʰ/ | ต | /t/ | ต | /t/ | ຕ | /t/ | พร | /pʰr/ | พร | |||

| ขร | /kʰr/ | ขร | ตร | /tr/ | ตร | พล | /pʰl/ | พล | |||||||||

| ขล | /kʰl/ | ขล | ป | /p/ | ป | /p/ | ປ | /p/ | |||||||||

| ปร | /pr/ | ปร | |||||||||||||||

| ปล | /pl/ | ปล | |||||||||||||||

| Thai | Isan | Lao | Gloss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| เพลง phleng |

/pʰleːŋ/ | เพลง phleng |

/pʰéːŋ/ | ເພງ phéng |

/pʰéːŋ/ | 'song' |

| ขลุ่ย khlui |

/kʰlùj/ | ขลุ่ย khlui |

/kʰūj/ | ຂຸ່ຍ khouay |

/kʰūj/ | 'flute' |

| กลาง klang |

/klaːŋ/ | กลาง klang |

/kàːŋ/ | ກາງ kang |

/kàːŋ/ | 'centre' 'middle' |

| ครอบครัว khropkhrua |

/kʰrɔ̑ːp kʰrua/ | ครอบครัว khropkhrua |

/kʰɔ̑ːp kʰúa/ | ຄອບຄົວ khopkhoua |

/kʰɔ̑ːp kʰúːa/ | 'family' |

/r/ > /h/

Proto-Southwestern Tai initial voiced alveolar trill /r/ remained /r/ in Thai, although it is sometimes pronounced /l/ in informal environments, whereas Lao changed the sound to the voiceless glottal fricative /h/ in these environments. The sound change likely occurred in the mid-sixteenth century as the Tai Noi orthography after that period has the letter Lao letter 'ຮ' /h/, which was a variant of 'ຣ' /r/ used to record the sound change. The change also included numerous small words of Khmer origin such as hian ຮຽນ, /híːən/), 'to learn', which is rian (เรียน, /riːən/) in Thai, from Khmer riĕn (រៀន, /riən/).

| PSWT | Thai | Isan | Lao | Gloss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *rim | ริม rim |

/rim/ | ฮิม him |

/hím/ | ຮິມ him |

/hím/ | 'edge', 'rim', 'shore' (Lao/Isan) |

| *rak | รัก rak |

/rák/ | ฮัก hak |

/hāk/ | ຮັກ hak |

/hāk/ | 'to love' |

| *rɔn | ร้อน ron |

/rɔ́ːn/ | ฮ้อน hon |

/hɔ̑ːn/ | ຮ້ອນ hon |

/hɔ̑ːn/ | 'to be hot' |

| *rɯə | เรือ ruea |

/rɯa/ | เฮือ huea |

/hɯ́a/ | ເຮືອ hua |

/hɨ́ːa/ | 'boat' |

/r/ > /l/

The shift of Proto-Southwestern Tai */r/ to /h/ in Lao was inconsistent, with some factors that prevented the transition. Instead, these situations led to the shift of /r/ to the alveolar lateral approximant /l/, similar as to what occurs in informal, casual Thai. Polysyllabic loan words from Khmer as well as Indic sources such as Khmer and Pali may have seemed too 'foreign' compared to the monosyllabic loan words that may have been regarded as native, somewhat similar to English 'beef', ultimately from French boeuf but fully anglicized in spelling and pronunciation, versus more evidently French loan words such as crème anglaise, which retains a more French-like pronunciation. Thai speakers sometimes use /l/ in place of /r/ in relaxed, basilectal varieties but this is deprecated in formal speech.

- rasa (ຣາຊາ raxa, /láː sáː/) from Sanskrit rājā (राजा, /raːdʒaː/), 'king', cf. Thai racha (ราชา, /raː tɕʰaː/), 'king'

- raka (ລາຄາ, /láː kʰáː/), 'price' from Sanskrit rāka (राक, /raːka/), 'wealth', cf. Thai raka (ราคา, /raː kʰaː/)

- charoen (ຈະເລີນ chaluen, /tɕáʔ lɤ́ːn/), 'prosperity', from Khmer camraeum (ចំរើន, /tɕɑm raən/), cf. Thai charoen (เจริญ, /tɕàʔ rɤːn/)

- rabam (ລະບຳ, /lāʔ bam/, 'traditional dance', from Khmer rôbam (របាំ, /rɔ bam/), cf. Thai rabam (ระบำ, /ráʔ bam/)

Lao and Thai both have digraphs, or in the case of Lao ligatures, that consist of a silent /h/ that was historically pronounced at some ancient stage of both languages, but now serves as a mark of tone, shifting the sound to a high-class consonant for figuring out tone. The /h/ may have prevented the assimilation of these words to /h/, as these end up as /l/ in Lao. Similarly, this may have also prevented /r/ to /h/ in Khmer loan words where it begins the second syllable.

- rue (ຫຼື/ຫລື lu, /lɯ̌ː/) versus rue (หรือ, /rɯ̌ː/), 'or' (conjunction)

- lio (ຫຼີ່ວ/ຫລີ່ວ, /līːw/ versus ri (หรี่, /rìː/), 'to squint' (one's eyes)

- kamlai (ກຳໄລ, /kam láj/), 'profit', from Khmer kâmrai (កំរៃ, /kɑm ray/), cf. Thai kamrai (กำไร, /kam raj/)

- samrap (ສຳລັບ samlap, /săm lāp/), 'for' (the purpose of, to be used as, intended as), from Khmer sâmrap (សំរាប់, /sɑmrap/), cf. Thai samrap (สำหรับ, /sǎm ráp/)

There are a handful of words where the expected conversion to /h/ did not take place, thus yielding /l/. In some cases, even in the Lao of Laos, this can be seen as historic Siamese influence, but it also may have been conservative retentions of /r/ in some words that resisted this change. For example, Isan has both hap (ฮับ, ຮັບ, /hāp/) and lap (รับ, ລັບ, /lāp/), both of which mean 'to receive' and are cognates to Thai rap (รับ, /ráp/), and the lap variety in Isan and parts of Laos, especially the south, may be due to Thai contact. In other cases, it is because the words are recent loans from Thai or other languages. In Isan, younger speakers often use /l/ in place of /h/ due to language shift.

- ro (ລໍ, /lɔ́ː/), 'to wait, to wait for', cf. Thai ro (รอ, /rɔː/)

- rot (ຣົຖ/ລົດ/ລົຖ/ lôt, /lōt/), 'car' or 'vehicle', cf. Thai rot (รถ, /rót/)

- lam (ລຳ, /lám/), 'to dance', cf. Thai ram (รำ, /ram/)

- rom (ໂຣມ/ໂລມ rôm, /lóːm/), 'Rome', cf. Thai rom (โรม, /roːm/)

- rangkai (ร่างกาย, /lāːŋ kaːj/) (Isan youth), traditionally hangkai (hāːŋ kaːj, ຮ່າງກາຽ, /hāːŋ kaːj/), 'body' (anatomic), cf. Thai rangkai (ร่างกาย, /râːŋ kaːj/)

/tɕʰ/ > /s/

Proto-Tai */ɟ/ and */ʑ/ had merged into Proto-Southwestern Tai */ɟ/, which developed into /tɕʰ/ in Thai, represented by the Thai letter 'ช'. Only a small handful of Proto-Tai words with */č/ were retained in Proto-Southwestern Tai, represented by the Tai letter 'ฉ', but this also developed into /tɕʰ/ in Thai and most words with 'ฉ' are either Khmer, Sanskrit or more recent loan words from Chinese dialects, particularly Teochew (Chaoshan Min). Thai also uses the letter 'ฌ' which only occurs in a handful of Sanskrit and Pali loan words where it represented /ɟʱ/, but in Thai has the pronunciation /tɕʰ/. Lao has developed /s/ where Thai has /tɕʰ/, with the letter 'ຊ' /s/, but romanized as 'x', is used to represent cognate words with Thai 'ช' or 'ฌ' whereas Thai 'ฉ' is replaced by Lao 'ສ' /s/ in analogous environments.

Isan speakers will sometimes substitute the Thai letter 'ซ' /s/ in place of Thai 'ช' /tɕʰ/ in cognate words, but this is never done to replace 'ฌ' /tɕʰ/ and sometimes avoided in formal, technical or academic word of Khmer, Sanskrit and Pali origins even if the pronunciation is still /s/, although educated Isan speakers and Isan youth may you use /tɕʰ/ due to code-switching or language shift. Similarly, the letter 'ฉ' /tɕʰ/ is usually retained even if it is better approximated by tone and phonology by 'ส' /s/ as is done in similar environments in Lao.

| Source | Thai | Isan | Lao | Gloss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| */ʑaɰ/1 | เช่า chao |

/tɕʰâw/ | เซ่า sao |

/sāw/ | ເຊົ່າ xao |

/sāw/ | 'to hire' | |

| */ʑaːj/1 | ชาย chai |

/tɕʰaːj/ | ซาย sai |

/sáːj/ | ຊາຽ2/ຊາຍ xai |

/sáːj/ | 'male' | |

| */ɟaː/1 | ชา cha |

/tɕʰaː/ | ซา sa |

/sáː/ | ຊາ xa |

/sáː/ | 'tea' | |

| */ɟɤ/1 | ชื่อ chue |

/tɕʰɯ̂ː/ | ซื่อ sue |

/sɯ̄ː/ | ຊື່ xu |

/sɨ̄ː/ | 'name', 'to be called' | |

| Khmer ឆ្លង chhlâng |

/cʰlɑːŋ/ | ฉลอง chalong |

/tɕʰàʔ lɔ̌ːŋ/ | ฉลอง chalong |

/sáʔ lɔ̌ːŋ/ | ສລອງ2/ສະຫຼອງ2/ສະຫລອງ salong |

/sáʔ lɔ̌ːŋ/ | 'to celebrate' |

| */ɟuai/1 | ช่วย chui |

/tɕʰûaj/ | ซ่อย soi |

/sɔ̄j/ | ຊ່ຽ2/ຊ່ວຽ2/ຊ່ອຍ xoi |

/sɔ̄ːj/ | 'to help' | |

| Pali झान jhāna |

/ɟʱaːna/ | ฌาน chan |

/tɕʰaːn/ | ฌาน chan |

/sa̋ːn/ | ຊານ xan |

/sáːn/ | 'meditation' |

| Sanskrit छत्र chatra |

/cʰatra/ | ฉัตร chat |

/tɕʰàt/ | ฉัตร chat |

/sát/ | ສັດ sat |

/sát/ | 'royal parasol' |

| Teochew 雜菜 zap cai |

/tsap˨˩˧ tsʰaj˦̚ / | จับฉ่าย chapchai |

/tɕàp tɕʰàːj/ | จับฉ่าย chapchai |

/tɕǎp sāːj/ | ຈັບສ່າຽ2/ຈັບສ່າຍ/ chapsai |

/tɕáp sāːj/ | 'Chinese vegetable soup' |

/j/ < /ŋ/ and /j/

Lao retains a distinction with some words retaining a voiced palatal nasal /ɲ/ from the merger Proto-Southwestern Tai */ɲ/ and */ʰɲ/ and some words with /j/ derived from the merger of Proto-Southwestern Tai */j/ and */ˀj/. The change may have persisted into Thai after the adoption of writing, as some words provide clues to their etymology. For example, Proto-Southwestern Tai */ɲ/ and */ʰɲ/ correspond to the Central and Southern Thai spellings 'ญ' and 'หญ' whereas */j/ and */ˀj/ correspond to Central and Southern Thai spellings 'ย' and 'อย', respectively, all of which have merged in pronunciation to /j/ in Thai, although as this pronunciation was likely lost shortly after literacy, not all Thai words have this corresponding spelling. Thai also uses the letter 'ญ' in words of Khmer, Sanskrit and Pali where the source language has /ɲ/ but these words now have /j/ pronunciation.

Lao maintains the distinction with the letters 'ຍ' /ɲ/ and 'ຢ' /j/, but /j/ is a rarer outcome in Lao and most instances of Thai 'ย' and 'ญ' or digraphs 'หย' and 'หญ' will result in Lao 'ຍ' /ɲ/ or 'ຫຽ/ຫຍ' /ɲ/. With a few exceptions, only Proto-Southwestern Tai */ˀj/ yields /j/. Lao, unlike Thai, has also adopted Khmer, Sanskrit and Pali loan words and retains the /ɲ/ pronunciation of the loan source languages, but has also converted the consonantal /j/ into /ɲ/ in borrowings. The Lao letter 'ຍ' also represents /j/, but only in diphthongs and triphthongs as a final element. As the Lao language of Isan is written in Thai according to Thai spelling rules, the phonemic distinction between /j/ into /ɲ/ cannot be made in the orthography, thus Isan speakers write ya 'ยา', which suggests ya (ยา, /jaː/), 'medicine' but is also used for [n]ya (ยา, ຍາ, /ɲáː/), an honorary prefix used to address a person who is same in age as one's grandparents. These are distinguished in Lao orthography, but Isan speakers either use context or a tone mark, as they differ in tone, to differentiate the words.

| Source | Thai | Isan | Lao | Gloss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| */ɲuŋ/1 | ยุง yung |

/juŋ/ | ยูง [n]yung |

/ɲúːŋ/ | ຍູງ gnoung |

/ɲúːŋ/ | 'mosquito' | |

| */ɲok/1 | ยก yok |

/jók/ | ยก [n]yok |

/ɲōk/ | ຍົກ gnok |

/ɲōk/ | 'to lift' | |

| */ʰɲiŋ/1 | หญิง ying |

/yǐŋ/ | ญิง [n]ying |

/ɲíŋ/ | ຍິງ gning |

/ɲíŋ/ | 'girl' | |

| */ʰɲaːp/1 | หยาบ yap |

/jàːp/ | หยาบ [n]yap |

/ɲȁːp/ | ຫຽາບ2/ຫຍາບ gnap |

/ɲȁːp/ | 'coarse' (texture) | |

| */jaːw/1 | ยาว yao |

/jaːw/ | ยาว [n]yao |

/ɲáːw/ | ຍາວ gnao |

/ɲáːw/ | 'long in length' | |

| */jaːm/1 | ยาม yam |

/jaːm/ | ยาม [n]yam |

/ɲáːm/ | ຍາມ gnam |

/ɲáːm/ | 'time', 'season' | |

| */ˀjuː/1 | อยู่ yu |

/jù:/ | อยู่ yu |

/júː/ | ຢູ່ you |

/jūː/ | 'to be' (condition, location) | |

| */ˀja:/1 | ยา ya |

/ja:/ | ยา ya |

/jaː/ | ຢາ ya |

/jaː/ | 'medicine' | |

| Sanskrit यक्ष yakṣa |

/jakʂa/ | ยักษ์ yak |

/ják/ | ยักษ์ [n]yak |

/ɲāk/ /ják/2 |

ຍັກສ໌2/ຍັກ gnak |

/ɲāk/ | 'ogre', 'giant' |

| Pali ञतति ñatti |

/ɲatti/ | ญัตติ yatti |

/ját tì/ | ญัตติ [n]yatti |

/ɲāt tǐ/ /játˈtìʔ/ |

ຍັຕຕິ2/ຍັດຕິ gnatti |

/ɲāt tí/ | 'parliamentary motion' |

/m/ > /l/

The Proto-Southwestern Tai cluster *ml was simplified, producing an expected result of /l/ in Thai and /m/ in Lao. The Saek language, a Northern Tai language distantly related to Thai and Lao preserves these clusters. For instance, Proto-Southwestern Tai *mlɯn, 'to open the eyes', is mlong in Saek (มลอง, ມຼອງ, /mlɔːŋ/) but appears as luem (ลืม, /lɯːm/) and muen (มืน, ມືນ mun, /mɯ́ːn/) in Lao.[7]

| PSWT | Isan | Thai | Lao | Gloss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *mlɯn | มื่น meun |

/mɯ̄ːn/ | ลื่น leun |

/lɯ̂ːn/ | ມື່ນ mun |

/mɨ̄ːn/ | 'slippery' |

| *mlaːŋ | ม้าง mang |

/mȃːŋ/ | ล้าง lang |

/láːŋ/ | ມ້າງ mang |

/mȃːŋ/ | 'to destroy', 'to obliterate' |

| *mlen | เม็น men |

/mén/ | เล็น len |

/len/ | ເມັ່ນ mén |

/mén/ | 'louse' |

/w/ > /ʋ/

Lao speakers generally pronounce cognates of Thai with initial /w/ as the voiced labiodental approximant /ʋ/, similar to a faint 'v', enough so that the French chose 'v' to transcribe the Lao letter 'ວ' /ʋ/. The letter is related to Thai 'ว' /w/. The sound /ʋ/ is particularly noticeable in the Vientiane and Central Lao dialects, with a strong pronunciation favored by the élite of Vientiane. In Isan, the rapid but forced resettlement of the people of Vientiane and surrounding areas to the right bank greatly boosted the Lao population, but likely led to some dialect leveling, which may explain the prevalence of /ʋ/ throughout the region, regardless of personal Isan dialect. The replacement is not universal, especially in Laos, but a shift towards /w/ is also occurring in Isan due to the persistent pressures of the Thai language since the sound /ʋ/ is considered provincial, being different from Thai, as opposed to Laos where it is the prestigious pronunciation. Due to the difference in pronunciation, the French-based system used in Laos uses 'v' whereas the English-based Thai system of romanization uses 'w', so the Lao city of Savannakhét would be rendered 'Sawannakhet' if using the Thai transcription.

| Isan | Thai | Lao | Gloss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| เวร wen |

/wéːn/ | เวร wen |

/weːn/ | ເວນ vén |

/ʋéːn/ | 'sin' |

| เวียง wiang |

/wíaŋ/ | เวียง wiang |

/wiaŋ/ | ວຽງ viang |

/ʋíːəŋ/ | 'walled city' |

| สวรรค์ sawan |

/sáʔ wǎn/ | สวรรค์ sawan |

/sàʔ wǎn/ | ສະຫວັນ/ສວັນ/ສວັນຄ໌ savan |

/sáʔ ʋǎn/ | 'paradise' |

| หวาน wan |

/wǎːn/ | หวาน wan |

/wǎːn/ | ຫວານ van |

/ʋǎːn/ | 'sweet' |

| วิษณุ wisanu |

/wīt sáʔ nū/ | วิษณุ wisanu |

/wít sàʔ nú/ | ວິດສະນຸ/ວິສນຸ vitsanou |

/ʋīt sáʔ nū/ | 'Vishnu' |

/k/ > /t͡ɕ/

Another influence of the massive migration of the people of Vientiane to the right bank is the common tendency to replace the voiceless velar plosive /k/ with the voiceless alveolo-palatal affricate /t͡ɕ/. For instance, the people of the city of Khon Chaen, more generally referred to as Khon Kaen (ขอนแก่น, ຂອນແກ່ນ Khon Kèn, /kʰɔ̆ːn kɛ̄n/) in formal contexts, refer to their city as Khon Chaen (ขอนแจ่น, *ຂອນແຈ່ນ, /kʰɔ̆ːn t͡ɕɛ̄n/) in more relaxed settings. In Laos, this is particularly an informal feature specific to Vientiane Lao but is not used in the official written and spoken standard as it is an informal variant, whereas in Isan, it is commonly used but deprecated as a regional mispronunciation. It is also limited to certain words and environments.

| Isan | Thai | Lao | Gloss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| เกี้ยว/เจีัยว kiao/chiao |

/kîaw/, /tɕîaw/ | เกี้ยว kiao |

/kîaw/ | ກ້ຽວ vén |

/kîaw/, /tɕîaw/ | 'to woo', 'to flirt' |

| เกี่ยง/เจียง kiang/chiang |

/kíaŋ/, /tɕíaŋ/ | เกี่ยง kiang |

/kìaŋ/ | ກ່ຽງ kiang |

/kīːəŋ/, /t͡ɕīːəŋ/ | 'to argue', 'to disagree' |

| แก้ม/แจ่ม kaem/chaem |

/kɛ̂ːm/, /tɕɛ̂ːm/ | แก้ม kaem |

/kɛ̂ːm/ | ແກ້ມ kèm |

/kɛ̂ːm/, /tɕɛ̂ːm/ | 'cheek' |

C/w/ diphthongization

Lao innovated a diphthongization that assimilates the /w/ in instances of /kw/ and /kʰw/ in certain environments. This is triggered by the vowels /a/, /aː/, /aːj/ and /am/, but the cluster is retained in all other instances. The /w/ is converted to /uː/ and the vowel is shortened to /ə/. This is not shown in the orthography, as it must have evolved after the adoption of the Lao script in the fourteenth century. Cognate words in Lao where this diphthongization occurs have no alteration in spelling from Thai counterparts. For example, the Thai word for 'to sweep' is kwat (กวาด, /kwàːt/) but is kwat (ກວາດ kouat, /kȕːat/) and has the suggested pronunciation /kwȁːt/ but is pronounced *kuat (*ກວດ kouat). The counterpart of Thai khwaen (แขวน, kʰwɛ̌ːn), 'to hang' (something) is also khwaen (ແຂວນ khwèn, /kʰwɛ̆ːn/) since the vowel /ɛː/ does not trigger diphthongization.

The vowels /a/, /aː/, /aːj/ and /am/ correspond to Thai '◌ั◌', '◌า', '◌าย' and '◌ำ' and the Lao '◌ັ◌', '◌າ', '◌າຽ/◌າຍ' and '◌ຳ'. The clusters that can undergo this transformation are /kw/, Thai 'กว' and Lao 'ກວ' or /kw/, Thai 'ขว' and 'คว and Lao 'ຂວ' and 'ຄວ'. The non-diphthongized pronunciations as used in Thai are also used by some Isan speakers as a result of Thai influence. In Laos, non-diphthongization is not incorrect, but may sound like a Thai-influenced hypercorrection or very pedantic. As it is the normal pronunciation in Laos and Isan, it limits the instances of consonant clusters that are permissible.

| Cluster | Thai | Isan | Lao | Gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suggested Pronunciation | Actual Pronunciation | Suggested Pronunciation | Actual Pronunciation | |||

| C/w/-/aː/-[C] | Cวา | Cวา | Cัว, CวC | Cວາ | *Cົວ, *CວC | 'wide' |

| กว้าง kwang /kwâːŋ/ |

กว้าง kwang */kwâːŋ/ |

*ก้วง *kuang /kûaŋ/ |

ກວ້າງ *kwang */kwâːŋ/ |

*ກ້ວງ kouang /kûːəŋ/ | ||

| C/w/-/aːj/ | Cวาย | Cวาย | *Cวย | Cວາຍ | *Cວຍ | 'water buffalo' |

| ควาย khwai /kʰwaːj/ |

ควาย *khwai */kʰwáːj/ |

*ควย khui /kʰúaj/ |

ຄວາຍ *khwai */kʰwáːj/ |

*ຄວຍ khoui /kʰúːəj/ | ||

| C/w/-/a/-C | CวัC | CวัC | *CวC | CວັC | *CວC | 'to scoop' 'to gouge' |

| ควัก khwak /kʰwák/ |

ควัก khwak */kʰwāk/ |

*ควก *khuak /kʰūak/ |

ຄວັກ *khwak */kʰwāk/ |

*ຄວກ khouak /kʰūːək/ | ||

| C/w/-/am/ | Cวำ | Cวำ | *Cวม | Cວຳ | *Cວມ | 'to capsize a boat' |

| คว่ำ khwam /kʰwâm/ |

คว่ำ khwam */kʰwâm/ |

*ค่วม *khuam /kʰuām/ |

ຄວ່ຳ *khoam */kʰwām/ |

*ຄວ່ມ khouam /kʰuːām/ | ||

| C/w/-/ɛː/C | แCว | แCว | ແCວ | 'to hang' (an object) | ||

| แขวน khwaen /kʰwɛ̌ːn/ |

แขวน khwaen /kʰwɛ̆ːn/ |

ແຂວນ khwèn /kʰwɛ̆ːn/ | ||||

/ua/ > /uːə/

The Thai diphthongs and triphthongs with the component /ua/ undergo a lengthening of the /u/ to /uː/ and shortens the /a/ to /ə/, although the shortened diphthong can sound like /uː/ to Thai speakers. In Thai, this includes the vowels /ua/ represented medially by '◌ว◌' and finally by '◌ัว', /uaʔ/ by '◌ัวะ' and the final triphthong /uaj/ by '◌วย'. Lao has /uːə/ represented medially by '◌ວ◌' and finally by '◌ົວ', /uːəʔ/ by '◌ົວະ' and the final triphthong /uːəj/ by '◌ວຽ/◌ວຍ'. This may have been another innovation, like C/w/ diphthongization, that occurred after the adoption of writing as it is not represented orthographically.

| Thai | Isan | Lao | Gloss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| หัว hua |

/hǔa/ | หัว hua |

/hŭa/ | ຫົວ houa |

/hŭːə/ | 'head' |

| ร่วม ruam |

/rûam/ | ฮ่วม huam |

/hūam/ | ຮ່ວມ houam |

/hūːəm/ | 'to share', 'to participate' |

| ลัวะ lua |

/lúaʔ/ | ลัวะ lua |

/lūaʔ/ | ລົວະ loua |

/lūːəʔ/ | 'Lawa people' |

| มวย muai |

/muaj/ | มวย muai |

/múaj/ | ມວຍ mouai |

/múːəj/ | 'boxing' |

/ɯ/ > /ɨ/

The close back unrounded vowel /ɯ/ is centralized to the close central unrounded vowel /ɨ/ in Lao, which is not found in Thai. This also applies to all variants of /ɯ/ that occur in Thai, i.e., all cognates with instances of Thai /ɯ/ are Lao /ɨ/, including diphthongs and triphthongs that feature this vowel element. Some very traditional dialects of Southern Lao and the Phuan dialect front the vowel all the way to /iː/.

| Thai | Isan | Lao | Gloss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| หมึก | /mɯ̀k/ | หมึก | /mɯ́k/ | ມຶກ | /mɨ̄k/ | 'squid' |

| ลือ | /lɯː/ | ลือ | /lɯ́ː/ | ລື | /lɨ́ː/ | 'rumour'/'rumor' (US) |

| เมื่อไร | /mɯ̂a raj/ | เมื่อใด | /mɯ́a daj/ | ເມື່ອໃດ | /mɨ̄ːə dàj/ | 'when' |

| เรื่อย | /rɯ̂aj/ | เรื่อย | /lɯ̄aj/ | ເລຶ້ອຽ/ເລຶ້ອຍ | /lɨ̑ːəj/ | 'often', 'repeatedly' |

/ɤ/ > /ɘ/

The close-mid back unrounded vowel /ɤ/ is centralized to the close-mid central unrounded vowel /ɘ/ in Lao. Similar to the conversion of /ɯ/ to /ɨ/, it also affects all instances in diphthongs as well.

| Thai | Isan | Lao | Gloss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| เงิน, ngoen | /ŋɤn/ | เงิน, ngoen | /ŋɘ́n/ | ເງິນ, nguen | /ŋɘ́n/ | 'money' |

| เผลอ, phloe | /pʰlɤ̌/ | เผลอ, phloe | /pʰɘ́/ | ເຜິ, pheu | /pʰɘ́/ | 'to make a mistake', 'unaware' |

| เดิม, doem | /dɤːm/ | เดิม, doem | /dɘːm/ | ເດີມ, deum | /dɘːm/ | 'original', 'former' |

| เคย, khoei | /kʰɤːj/ | เคย, khoei | /kʰɘ́ːj/ | ເຄີຽ/ເຄີຍ, kheui | /kʰɘ́ːj/ | 'to be accustomed to', 'to be habitual to' |

Epenthetic vowels

Abugida scripts traditionally do not notate all vowels, especially the short vowel /a/, usually realized as /aʔ/ in Thai and Lao phonology. This especially affects the polysyllabic loan words of Sanskrit, Pali or Khmer derivation. Instances of when or when not to pronounce a vowel have to be learned individually as the presence of the vowel is inconsistent. For example, the Sanskrit word dharma (धर्म, /d̪ʱarma/), which can mean 'dharma', 'moral' or 'justice', was borrowed into Thai as simply tham (ธรรม /tʰam). As a root, it appears as simply tham as in thamkaset (ธรรมเกษตร /tʰam kàʔ sèːt/) 'land of justice' or 'righteous land' with the /aʔ/ or thammanit (ธรรมนิตย์ /tʰam máʔ nít/), 'moral person' with /aʔ/. This is not always justified by etymology, as the terms derive from Sanskrit dharmakṣetra (धर्मक्षेत्र, /d̪ʱarmakʂetra/)—actually signifies 'pious man' in Sanskrit—and dharmanitya (धर्मनित्य, /d̪ʱarmanit̪ja/), respectively, both of which feature a pronounced but unwritten /a/. Lao and most Isan speakers in relaxed environments will pronounce the 'extra' vowel yielding *thammakaset (ธรรมเกษตร, ທັມມະກເສດ/ທັມມະກເສດຣ໌/ທຳມະກະເສດ thammakasét, /tʰám māʔ ká sȅːt/) and thammanit (ธรรมนิตย์, ທັມມະນິດ/ທັມມະນິຕຍ໌/ທຳມະນິດ, /tʰám māʔ nīt/). There are also instances where Thai has the epenthetic vowel lost in Lao, such as krommathan (กรมธรรม์, /krom maʔ tʰan/), 'debt contract', whereas Lao has nativized the pronunciation to kromtham (ກົມທັນ/ກົມທໍາ kômtham, //kòm tʰám/). This is an exception, as the extra vowel is a sign of Lao-retained pronunciation such as Thai chit (จิตร, /jìt/), 'paiting' from Sanskrit citra (चित्र, /t͡ʃit̪ra/), which is chit (จิตร, ຈິຕຣ໌/ຈິດ, /t͡ɕít/), chit[ta] (จิตร, ຈິດຕະ chitta, /t͡ɕít táʔ/) or extremely epentheticized chit[tara] (จิตร, ຈິດຕະຣະ/ຈິດຕະລະ chittala, /t͡ɕít táʔ lā/ in Isan.

As another feature of Isan that deviates from Thai, it is deprecated. Few Isan people are aware that the stigmatized pronunciations are actually the 'proper' Isan form inherited from Lao. Many of these loan words are limited to academic and formal contexts that usually trigger code-switching to formal Thai, thus Isan speakers may pronounce these words more akin to Thai fashion although to varying degrees of adaptation to Isan pronunciation. Lao speakers also tend to insert epenthetic vowels in normal speech, as opposed to standard Thai where this is less common, thus 'softening' the sentence and making dialogue-less staccato. For instance, the Isan phrase chak noi (จักน้อย, ຈັກນ້ຽ/ຈັກນ້ອຽ/ຈັກນ້ອຍ /tɕʰák nɔ̑ːj/), which means 'in just a bit' is often pronounced chak-ka noy (*จักกะน้อย /*tɕʰák káʔ nɔ̑ːj/, cf. Lao *ຈັກກະນ້ອຍ) but this may be perceived as 'slurred' speech to Thai speakers.

| Isan | Thai | Lao | Sanskrit/Pali | Gloss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| จิตวิทยา chitwithaya |

/tɕǐt tǎʔ wīt tʰāʔ ɲáː/1 /tɕǐt wít tʰáʔ ɲáː/2 |

จิตวิทยา chitwithaya |

/tɕìt wít tʰáʔ jaː/ | ຈິດຕະວິດທະຍາ chittavitthagna (*จิดตะวิดทะยา) |

/tɕít táʔ ʋít tʰāʔ ɲáː/ | चित् + चित्विद्या cit + vidya |

/tɕit/ + /ʋid̪jaː/ | 'psychology' |

| มัสยา matya |

/māt sá ɲăː/1 /māt ɲăː/2 |

มัสยา matya |

/mát jaː/ | ມັສຍາ/ມັດສະຍາ matsagna (*มัดสะยา) |

/māt sáʔ ɲăː/ | मत्स्य matsya |

/mat̪sja/ | 'fish' |

| กรมธรรม์ kommathan |

/kom tʰám/1 /kom māʔ tʰán/ |

กรมธรรม์ kommathan |

/krom máʔ tʰan/ | ກົມທໍາ/ກົມທັນ ກົມມະທັນ kômtham kômmatham (*กมทัม) (*กมมะทัน) |

/kòm tʰám/ /kòm māʔ tʰán/ |

क्रमधर्म kramadharma |

/kramad̪ʱarma/ | 'debt contract' |

| อดีตชาติ aditchat |

/ʔǎ dìːt tǎʔ sȃːt/1 /ʔǎ dìːt sȃːt/2 |

อดีตชาติ | /ʔà dìːt tɕʰâːt/ | ອະດີດຊາດ ອະດິດຕະຊາດ aditxat adittaxat (*อดีดซาด) (*อดีดตะซาด) |

/ʔá dȉːt táʔ sȃːt/ /ʔá dȉːt sȃːt/ |

आदिता + जाति aditya + jati |

/ad̪it̪ja/ + /dʒat̪i/ | 'previous incarnation' |

| จิตรกรรม chitrakam |

/tɕǐt tǎʔ kam/ | จิตรกรรม chitrakam |

/tɕìt tràʔ kam/ | ຈິດຕະກັມ chittakam (*จิดตะกัม) |

/tɕít táʔ kam/ | चित्रकर्म citrakarma |

/tɕit̪rakarma/ | 'painting' |

| วาสนา watsana |

/wȃːt sáʔ năː/ /wáː sáʔ năː/3 |

วาสนา watsana (*wasana) |

/wâːt sàʔ nǎː/ /waː sàʔ nǎː/3 |

ວາດສນາ/ວາສນາ/ວາດສະໜາ vatsana (*วาดสะหนา) |

/ʋȃːt sáʔ năː/ | वस्न vasna |

/ʋasna/ | 'fortune' |

Grammatical differences

Classifiers

| Isan | Thai | Lao | Category |

| คน (ฅน), kʰón | คน (ฅน), kʰōn | ຄົນ, kʰon | People in general, except clergy and royals. |

| คัน, kʰán | คัน, kʰān | ຄັນ, kʰán | Vehicles, also used for spoons and forks in Thai. |

| คู่, kʰuː | คู่, kʰûː | ຄູ່, kʰūː | Pairs of people, animals, socks, earrings, etc. |

| ซบับ, saʔbap | ฉบับ, tɕʰaʔbàp | ສະບັບ, saʔbáp | Papers with texts, documents, newspapers, etc. |

| โต, toː | ตัว, tūa | ໂຕ, tòː | Animals, shirts, letters; also tables and chairs (but not in Lao). |

| กก, kok | ต้น, tôn | ກົກ, kók | Trees. Lao ຕົ້ນ is used in all three for columns, stalks, and flowers. |

| หน่วย, nuaj | ฟอง, fɔ̄ːŋ | ໜ່ວຍ, nūaj | Eggs, fruits, clouds. ผล (pʰǒn) used for fruits in Thai. |

Pronouns

Although all the Tai languages are pro-drop languages, which omit pronouns if their use is unnecessary due to context, especially in informal contexts, they are restored in more careful speech. Lao frequently uses the first- and second-person pronouns and rarely drops them in speech compared to Thai, which can sometimes seem more formal and distant. More common is to substitute pronouns with titles of professions or extension of kinship terms based on age, thus it is very common for lovers or close friends to call each other 'brother' and 'sister' and to address the very elderly as 'grandfather' or 'grandmother'. Isan traditionally uses the Lao-style pronouns, although in formal contexts, the Thai pronouns are sometimes substituted as speakers adjust to the socially mandated use of Standard Thai in very formal events.

To turn a pronoun into a plural, it is most commonly prefixed with mu (ຫມູ່/ໝູ່ /mūː/) but the variants tu (ຕູ /tuː/) and phuak (ພວກ /pʰûak/) are also used by some speakers. These can also be used for the word hao, 'we', in the sense of 'all of us' for extra emphasis. The vulgar pronouns are used as a mark of close relationship, such as long-standing childhood friends or siblings and can be used publicly, but they can never be used outside of these relationships as they often change statements into very pejorative, crude or inflammatory remarks.

| Person | Isan | Thai | Lao | Gloss | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | ข้าน้อย khanoi |

/kʰȁː nɔ̑ːj/ | กระผม kraphom |

/kràʔ pʰǒm/ | ดิฉัน dichan |

/di tɕʰǎn/ | ຂ້ານ້ອຍ/ຂ້ານ້ອຽ khanoy |

/kʰȁː nɔ̑ːj/ | I (formal) |

| ข้อย khoi |

/kʰɔ̏j/ | ผม phom |

/pʰǒm/ | ฉัน | /tɕʰǎn/ | ຂ້ອຍ/ຂ້ອຽ khoy |

/kʰɔ̏ːj/ | I (common) | |

| กู ku |

/kuː/ | กู ku |

/kuː/ | ກູ kou |

/kuː/ | I (vulgar) | |||

| หมู่ข้าน้อย mu khanoi |

/mūː kʰȁː nɔ̑ːj/ | ข้าพเจ้า khaphachao |

/kʰâː pʰaʔ tɕâw/ | ຫມູ່ຂ້ານ້ອຍ/ໝູ່ຂ້ານ້ອຽ mou khanoy |

/mūː kʰȁː nɔ̑ːj/ | we (formal) | |||

| เฮา hao |

/hȃw/ | เรา rao |

/raw/ | ເຮົາ hao |

/hȃw/ | we (common) | |||

| หมู่เฮา mu hao |

/mūː hȃw/ | พวกเรา phuak rao |

/pʰûak raw/ | ຫມູ່ເຮົາ/ໝູ່ເຮົາ mou hao |

/mūː hȃw/ | ||||

| 2nd | ท่าน | /tʰāːn/ | ท่าน | /tʰân/ | ທ່ານ | /tʰāːn/ | you (formal) | ||

| เจ้า chao |

/tɕȃw/ | คุณ khun |

/kʰun/ | ເຈົ້າ chao |

/tɕȃw/ | you (common) | |||

| มึง mueng |

/mɯ́ŋ/ | มึง mueng |

/mɯŋ/ | ມຶງ meung |

/mɨ́ŋ/ | you (vulgar) | |||

| หมู่ท่าน mu than |

/mūː tʰāːn/ | พวกคุณ phuak khun |

/pʰûak kʰun/ | ຫມູ່ທ່ານ/ໝູ່ທ່ານ mou than |

/mūː tʰāːn/ | you (pl., formal) | |||

| หมู่เจ้า chao |

/mūː tɕȃw/ | คุณ khun |

/kʰun/ | ຫມູ່ເຈົ້າ chao |

/mūː tɕȃw/ | you (pl., common) | |||

| 3rd | เพิ่น phoen |

/pʰɤ̄n/ | ท่าน than |

/tʰân/ | ເພິ່ນ pheun |

/pʰə̄n/ | he/she/it (formal) | ||

| เขา khao |

/kʰăw/ | เขา khao |

/kʰǎw/ | ເຂົາ khao |

/kʰăw/ | he/she/it (common) | |||

| ลาว lao |

/láːw/ | ລາວ lao |

/láːw/ | ||||||

| มัน man |

/mán/ | มัน man |

/man/ | ມັນ man |

/mán/ | he/she/it (informal) | |||

| ขะเจ้า khachao |

/kʰáʔ tɕȃw/ | พวกท่าน phuak than |

/pʰûak tʰân/ | ຂະເຈົ້າ khachao |

/kʰáʔ tɕȃw/ | they (formal) | |||

| หมู่เขา mu khao |

/mūː kʰăw/ | พวกเขา phuak khao |

/pʰûak kʰáw/ | ຫມູ່ເຂົາ/ໝູ່ເຂົາ | /mūː kʰăw/ | they (common) | |||

| หมู่ลาว mu lao |

/mūː láːw/ | ຫມູ່ລາວ/ໝູ່ລາວ mou lao |

/mūː láːw/ | ||||||

Tones

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | ไม้เอก (อ่) | ไม้โท (อ้) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

| High (Thai/Vientiane) | Rising/Low-Rising | Low/Middle | Falling/Low-Falling | Low/Low-Falling | Low/Mid-Rising |

| High (Thai/Western Lao) | Rising/Low-Rising | Low/Middle | Falling/Low | Low/Low | Low/Low |

| Middle (Thai/Vientiane) | Middle/Low-Rising | Low/Middle | Falling/High-Falling | Falling/High-Falling | Low/Mid-Rising |

| Middle (Thai/Western Lao) | Middle/Rising-Mid-Falling | Low/Middle | Falling/Mid-Falling | Falling/Low | Low/Low |

| Low (Thai/Vientiane) | Middle/High-Rising | Falling/Middle | High/High-Falling | High/High-Falling | Falling/Middle |

| Low (Thai/Western Lao) | Middle/Rising-High-Falling | Falling/Low | High/High-Falling | High/Middle | Falling/Middle |

Even Thai words with clear cognates in Lao can differ remarkably by tone. Determining the tone of a word by spelling is complicated. Every consonant falls into a category of high, middle or low class. Then, one must determine whether the syllable has a long or a short syllable and whether it ends in a sonorant or plosive consonant and, if there are any, whatever tone marks may move the tone.[8] Thai กา ka, crow, has a middle tone in Thai, as it contains a mid-class consonant with a long vowel that does not end in a plosive. In Standard Lao, the same environments produce a low-rising tone /kàː/ but is typically /kâː/ or rising-mid-falling in Western Lao.

Despite the differences in pattern, the orthography used to write words is nearly the same in Thai and Lao, even using the same tone marks in most places, so it is knowing the spoken language and how it maps out to the rules of the written language that determine the tone. However, as the Tai languages are tonal languages, with tone being an important phonemic feature, spoken Lao words out of context, even if they are cognate, may sound closer to Thai words of different meaning. Thai คา kha /kʰaː/, 'to stick' is cognate to Lao ຄາ, which in Vientiane Lao is pronounced /kʰáː/, which may sound like Thai ค้า kha /kʰáː/, 'to trade' due to similarity in tone. The same word in some parts of Isan near Roi Et Province would confusingly sound to Thai ears like ขา kha /khǎː/ with a rising tone, where the local tone patterns would have many pronounce the word with a rising-high-falling heavier on the rising. Although a native Thai speaker would be able to pick up the meaning of the similar words of Lao through context, and after a period of time, would get used to the different tones (with most Lao speech varieties having an additional one or two tones to the five of Thai), it can cause many initial misunderstandings.

Lexical differences

Although the majority of Lao words are cognate with Thai, many basic words used in everyday conversation lack cognates in Thai. Some usages vary only by frequency or register. For instance, the Thai question word 'เท่าไหร่' is cognate with Lao 'ເທົ່າໃດ' /tʰāo daj/, but Lao tends to use a related variant form 'ท่อใด' /tʰɔ̄ː dàj/ and 'ທໍ່ໃດ' /tʰɔ̄ː dàj/, respectively, more frequently, although the usage is interchangeable and preference probably more related to region and person.

In other areas, Lao preserves the older Tai vocabulary. For example, the old Thai word for a 'glass', such as a 'glass of beer' or 'glass of water' was 'จอก' chok /tɕ̀ɔːk/, but this usage is now obsolete as the word has been replaced by Thai 'แก้ว' kaew /kɛ̑ːw/. Conversely, Lao continues to use 'ຈອກ' chok to mean 'glass' (of water) as /tɕ̀ɔ̏ːk/, but Lao 'ແກ້ວ' kéo /kɛ̑ːw/ retains the earlier meaning of Thai 'แก้ว' as 'gem', 'crystal' or 'glass' (material) still seen in the names of old temples, such as 'Wat Phra Kaew' or 'Temple of the Holy Gem'. Nonetheless, a lot of cognate vocabulary is pronounced differently in vowel quality and tone and sometimes consonant sounds to be unrecognizable or do not share a cognate at all. For example, Lao ບໍ່ /bɔː/ bo is not related to Thai ไม่ /mâj/, mai

| English | Isan | Lao | Thai |

| "no", "not" | บ่, /bɔ́ː/, bo | ບໍ່, /bɔː/, bo | ไม่, /mâj/, mai |

| "to speak" | เว้า, /wâw/, wao | ເວົ້າ, /vâw/, vao | พูด, /pʰûːt/, phut |

| "how much" | ท่อใด, /tʰɔ̄ː daj/, thodai | ທໍ່ໃດ, /tʰɔ̄ː dàj/, thodai | เท่าไหร่*, /tʰâw raj/, thaorai |

| "to do, to make" | เฮ็ด, /hēt/, het* | ເຮັດ, /hēt/, het | ทำ*, /tʰam/, tham |

| "to learn" | เฮียน, /hían/, hian | ຮຽນ, /hían/, hian | เรียน, /rian/, rian |

| "glass" | จอก, /tɕɔ̏ːk/, chok | ຈອກ, /tɕɔ̏ːk/, chok | แก้ว*, /kɛ̂ːw/, kaew |

| "yonder" | พู้น, /pʰûn/, phun | ພຸ້ນ, /pʰûn/, phoune | โน่น, /nôːn/, non |

| "algebra" | พีซคณิต, /pʰíː sāʔ kʰāʔ nīt/, phisakhanit | ພີຊະຄະນິດ/Archaic ພີຊຄນິດ, //, phixakhanit | พีชคณิต, /pʰîːt kʰáʔ nít/, phitkhanit |

| "fruit" | หมากไม้, /mȁːk mâj/, makmai | ໝາກໄມ້, /mȁːk mâj/, makmai | ผลไม้, /pʰǒn láʔ máːj/, phonlamai |

| "too much" | โพด, /pʰôːt/, phot | ໂພດ, /pʰôːt/, phôt | เกินไป, /kɤːn paj/, koenbai |

| "to call" | เอิ้น, /ʔɤ̂n/, oen | ເອີ້ນ, /ʔɤˆːn/, une | เรียก, /rîak/, riak |

| "a little" | หน่อยนึง, /nɔ̄j nɯ́ŋ/, noi neung | ໜ່ອຍນຶ່ງ/Archaic ໜ່ຽນຶ່ງ, /nɔ̄ːj nɯ¯ŋ/, noi nung | นิดหน่อย, /nít nɔ̀j/, nit noi |

| "house, home" | เฮือน, /hɯ́an/, heuan | ເຮືອນ*, /hɨ´ːan/, huane | บ้าน*, /bâːn/, ban |

| "to lower" | หลุด, /lút/, lut | ຫຼຸດ/ຫລຸດ), /lút/, lout | ลด, /lót/, lot |

| "sausage" | ไส้อั่ว, /sȁj ʔua/, sai ua | ໄສ້ອ່ົວ, /sȁj ʔūa/, sai oua | ไส้กรอก, /sâj krɔ̀ːk/, sai krok |

| "to walk" | ย่าง, /ɲāːŋ/, [n]yang | ຍ່າງ, /ɲāːŋ/, gnang | เดิน, /dɤːn/, doen |

| "philosophy" | ปรัซญา, /pát sā ɲáː/, pratsaya | ປັດຊະຍາ/Archaic ປັຊຍາ, /pát sā ɲáː/, patsagna | ปรัชญา, /pràt jaː/, pratya |

| "oldest child" | ลูกกก, /lûːk kǒk/, luk kok | ລູກກົກ, /lûːk kók/, louk kôk | ลูกคนโต, /lûːk kʰon toː/, luk khon to |

| "frangipani blossom" | ดอกจำปา, /dɔ̀ːk tɕam paː/ | ດອກຈຳປາ, /dɔ̏ːk tɕam paː/ | ดอกลั่นทม, /dɔ̀ːk lân tʰom/ |

| "tomato" | หมากเล่น, /mȁːk lēːn/, mak len | ໝາກເລັ່ນ, /mȁːk lēːn/, mak lén | มะเขือเทศ, /mâʔ kʰɯ̌ːa tʰêːt/, makheuathet |

| "much", "many" | หลาย, /lǎːj/, lai | ຫຼາຍ, /lǎːj/, lai | มาก, /mâːk/, mak |

| "father-in-law" | พ่อเฒ่า, /pʰɔ̄ː tʰȁw/, pho thao | ພໍ່ເຖົ້າ, /pʰɔ̄ː tʰȁw/, pho thao | พ่อตา, /pʰɔ̑ː taː/, pho ta |

| "to stop" | เซา, /sáw/, sao | ເຊົາ, /sáw/, xao | หยุด, /jùt/, yut |

| "to like" | มัก, /māk/, mak | ມັກ, /māk/, mak | ชอบ, /tɕʰɔ̂ːp/, chop |

| "good luck" | โซกดี, /sôːk diː/, sok di | ໂຊຄດີ, /sôːk diː/, xôk di | โชคดี, /tɕʰôːk diː/, chok di |

| "delicious" | แซบ, /sɛ̂ːp/, saep | ແຊບ, /sɛ̂ːp/, xèp | อร่อย, /ʔàʔ rɔ`j/, aroi |

| "fun" | ม่วน, /mūan/, muan | ມ່ວນ, /mūan/, mouane | สนุก, /sàʔ nùk/, sanuk |

| "really" | อีหลี, /ʔīː lǐː/, ili**** | ອີ່ຫຼີ, /ʔīː lǐː/, ili | จริง*, /tɕiŋ/, ching |

| "elegant" | โก้, /kôː/, ko | ໂກ້, /kôː/, kô | หรูหรา, /rǔː rǎː/, rura |

| "ox" | งัว, /ŋúa/, ngua | ງົວ, /ŋúa/, ngoua | วัว, /wua/, wua |

- 1 Thai เท่าไหร่ is cognate to Lao ເທົ່າໃດ, thaodai, /tʰāw daj/.

- 2 Thai แก้ว also exists as Lao ແກ້ວ,kèo /kɛ̑ːw/, but has the meaning of "gem".

- 3 Thai ทำ also exists as Lao ທຳ, tham, /tʰám/.

- 4 Lao ເຮືອນ also exists as formal Thai เรือน, reuan /rɯan/.

- 5 Thai บ้าน also exists as Lao ບ້ານ, bane, /bȃːn/.

- 6 Thai จริง also exists as Lao ຈິງ, ching, /tɕiŋ/.

See also

References

- Paul, L. M., Simons, G. F. and Fennig, C. D. (eds.). 2013. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Seventeenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved from http://www.ethnologue.com

- Keyes, Charles F. (1966). "Ethnic Identity and Loyalty of Villagers in Northeastern Thailand". Asian Survey.

- "Ausbau and Abstand languages". Ccat.sas.upenn.edu. 1995-01-20. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- Hesse-Swain, C. (2011). "Speaking in Thai, Dreaming in Isan: Popular Thai Television and Emerging Identities of Lao Isan Youth Living in Northeast Thailand" (Master's thesis, Edith Cowan University) (pp. 1–266). Perth, Western Australia.

- Draper, John (2010). "Inferring Ethnolinguistic Vitality in a Community of Northeast Thailand". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 31 (2): 135–148. doi:10.1080/01434630903470845. ISSN 0143-4632. S2CID 145258391.

- Davis, G. W. (2015). "The Story of Lao r: Filling in the Gaps". The Journal of Lao Studies, 2(2015), pp. 97-109.

- Pittayaporn, P. (2009). "Proto-Southwestern-Tai Revised: A New Reconstruction" Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Vol II. pp. 121–144. Canberra, Australia: Pacific Linguistics.

- Campbell, S., and Shaweevongs, C. (1957). The Fundamentals of the Thai Language (5th ed). Bangkok: Thai-Australia Co. Ltd.