Comparison of privilege authorization features

A number of computer operating systems employ security features to help prevent malicious software from gaining sufficient privileges to compromise the computer system. Operating systems lacking such features, such as DOS, Windows implementations prior to Windows NT (and its descendants), CP/M-80, and all Mac operating systems prior to Mac OS X, had only one category of user who was allowed to do anything. With separate execution contexts it is possible for multiple users to store private files, for multiple users to use a computer at the same time, to protect the system against malicious users, and to protect the system against malicious programs. The first multi-user secure system was Multics, which began development in the 1960s; it wasn't until UNIX, BSD, Linux, and NT in the late 80s and early 90s that multi-tasking security contexts were brought to x86 consumer machines.

Introduction to implementations

- Microsoft Windows

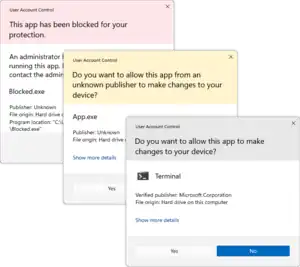

User Account Control prompt dialog box User Account Control prompt dialog box |

User Account Control (UAC): Included with Windows Vista and later Microsoft Windows operating systems, UAC prompts the user for authorization when an application tries to perform an administrator task.[1] |

| Runas: A command-line tool and context-menu verb introduced with Windows 2000 that allows running a program, control panel applet, or a MMC snap-in as a different user.[2] Runas makes use of the "Secondary Login" Windows service, also introduced with Windows 2000.[3] This service provides the capability to allow applications running as a separate user to interact with the logged-in user's desktop. This is necessary to support drag-and-drop, clipboard sharing, and other interactive login features. |

- Mac OS

|

Mac OS X includes the Authenticate dialog, which prompts the user to input their password in order to perform administrator tasks. This is essentially a graphical front-end of sudo command. |

- Unix and Unix-like

|

PolicyKit/pkexec: A privilege authorization feature, designed to be independent of the desktop environment in use and already adopted by GNOME[4] In contrast to earlier systems, applications using PolicyKit never run with privileges above those of the current user. Instead, they indirectly make requests of the PolicyKit daemon, which is the only program that runs as root. |

| su: A command line tool for Unix. su (substitute user) allows users to switch the terminal to a different account by entering the username and password of that account. If no user name is given, the operating system's superuser account (known as "root") is used, thus providing a fast method to obtain a login shell with full privileges to the system. Issuing an exit command returns the user to their own account. | |

| sudo: Created around 1980,[5] sudo is a highly configurable Unix command line tool similar to su, but it allows certain users to run programs with root privileges without spawning a root shell or requiring root's password.[6] | |

|

GKSu and GKsudo: GTK+ Graphical frontend to su and sudo.[7] GKsu comes up automatically when a supported application needs to perform an action requiring root privileges. A replacement, "gksu PolicyKit", which uses PolicyKit rather than su/sudo, is being developed as part of GNOME.[8] |

|

kdesu: A Qt graphical front-end to the su command for KDE.[9] |

|

kdesudo: A Qt graphical front-end to sudo that has replaced kdesu in Kubuntu, starting with Kubuntu 7.10.[10] |

|

ktsuss: ktsuss stands for "keep the su simple, stupid", and is a graphical version of su. The idea of the project is to remain simple and bug free. |

|

beesu: A graphical front-end to the su command that has replaced gksu in Red Hat based operating systems. It has been developed mainly for RHEL and Fedora.[11] |

| doas: sudo replacement since OpenBSD 5.8 (October 2015) |

Security considerations

Falsified/intercepted user input

A major security consideration is the ability of malicious applications to simulate keystrokes or mouse clicks, thus tricking or spoofing the security feature into granting malicious applications higher privileges.

- Using a terminal based client (standalone or within a desktop/GUI): su and sudo run in the terminal, where they are vulnerable to spoofed input. Of course, if the user was not running a multitasking environment (i.e. a single user in the shell only), this would not be a problem. Terminal windows are usually rendered as ordinary windows to the user, therefore on an intelligent client or desktop system used as a client, the user must take responsibility for preventing other malware on their desktop from manipulating, simulating, or capturing input.

- Using a GUI/desktop tightly integrated to the operating system: Commonly, the desktop system locks or secures all common means of input, before requesting passwords or other authentication, so that they cannot be intercepted, manipulated, or simulated:

- PolicyKit (GNOME - directs the X server to capture all keyboard and mouse input. Other desktop environments using PolicyKit may use their own mechanisms.

- gksudo - by default "locks" the keyboard, mouse, and window focus,[12] preventing anything but the actual user from inputting the password or otherwise interfering with the confirmation dialog.

- UAC (Windows) - by default runs in the Secure Desktop, preventing malicious applications from simulating clicking the "Allow" button or otherwise interfering with the confirmation dialog.[13] In this mode, the user's desktop appears dimmed and cannot be interacted with.

- If either gksudo's "lock" feature or UAC's Secure Desktop were compromised or disabled, malicious applications could gain administrator privileges by using keystroke logging to record the administrator's password; or, in the case of UAC if running as an administrator, spoofing a mouse click on the "Allow" button. For this reason, voice recognition is also prohibited from interacting with the dialog. Note that since gksu password prompt runs without special privileges, malicious applications can still do keystroke logging using e.g. the strace tool.[14] (ptrace was restricted in later kernel versions)[15]

Fake authentication dialogs

Another security consideration is the ability of malicious software to spoof dialogs that look like legitimate security confirmation requests. If the user were to input credentials into a fake dialog, thinking the dialog was legitimate, the malicious software would then know the user's password. If the Secure Desktop or similar feature were disabled, the malicious software could use that password to gain higher privileges.

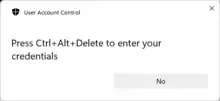

- Though it is not the default behavior for usability reasons, UAC may be configured to require the user to press Ctrl+Alt+Del (known as the secure attention sequence) as part of the authentication process. Because only Windows can detect this key combination, requiring this additional security measure would prevent spoofed dialogs from behaving the same way as a legitimate dialog.[16] For example, a spoofed dialog might not ask the user to press Ctrl+Alt+Del, and the user could realize that the dialog was fake. Or, when the user did press Ctrl+Alt+Del, the user would be brought to the screen Ctrl+Alt+Del normally brings them to instead of a UAC confirmation dialog. Thus the user could tell whether the dialog was an attempt to trick them into providing their password to a piece of malicious software.

- In GNOME, PolicyKit uses different dialogs, depending on the configuration of the system. For example, the authentication dialog for a system equipped with a fingerprint reader might look different from an authentication dialog for a system without one. Applications do not have access to the configuration of PolicyKit, so they have no way of knowing which dialog will appear and thus how to spoof it.[17]

Usability considerations

Another consideration that has gone into these implementations is usability.

Separate administrator account

- su require the user to know the password to at least two accounts: the regular-use account, and an account with higher privileges such as root.

- sudo, kdesu and gksudo use a simpler approach. With these programs, the user is pre-configured to be granted access to specific administrative tasks, but must explicitly authorize applications to run with those privileges. The user enters their own password instead of that of the superuser or some another account.

- UAC and Authenticate combine these two ideas into one. With these programs, administrators explicitly authorize programs to run with higher privileges. Non-administrators are prompted for an administrator username and password.

- PolicyKit can be configured to adopt any of these approaches. In practice, the distribution will choose one.

Simplicity of dialog

- In order to grant an application administrative privileges, sudo,[18] gksudo, and Authenticate prompt administrators to re-enter their password.

- With UAC, when logged in as a standard user, the user must enter an administrator's name and password each time they need to grant an application elevated privileges; but when logged in as a member of the Administrators group, they (by default) simply confirm or deny, instead of re-entering their password each time (though that is an option). While the default approach is simpler, it is also less secure,[16] since if the user physically walks away from the computer without locking it, another person could walk up and have administrator privileges over the system.

- PolicyKit requires the user to re-enter his or her password or provide some other means of authentication (e.g. fingerprint).

Saving credentials

- UAC prompts for authorization each time it is called to elevate a program.

- sudo,[6] gksudo, and kdesu do not ask the user to re-enter their password every time it is called to elevate a program. Rather, the user is asked for their password once at the start. If the user has not used their administrative privileges for a certain period of time (sudo's default is 5 minutes[6]), the user is once again restricted to standard user privileges until they enter their password again.

- sudo's approach is a trade-off between security and usability. On one hand, a user only has to enter their password once to perform a series of administrator tasks, rather than having to enter their password for each task. But at the same time, the surface area for attack is larger because all programs that run in that tty (for sudo) or all programs not running in a terminal (for gksudo and kdesu) prefixed by either of those commands before the timeout receive administrator privileges. Security-conscious users may remove the temporary administrator privileges upon completing the tasks requiring them by using the

sudo -kcommand when from each tty or pts in which sudo was used (in the case of pts's, closing the terminal emulator is not sufficient). The equivalent command for kdesu iskdesu -s. There is no gksudo option to do the same; however, runningsudo -knot within a terminal instance (e.g. through the Alt + F2 "Run Application" dialogue box, unticking "Run in terminal") will have the desired effect.

- Authenticate does not save passwords. If the user is a standard user, they must enter a username and a password. If the user is an administrator, the current user's name is already filled in, and only needs to enter their password. The name can still be modified to run as another user.

- The application only requires authentication once, and is requested at the time the application needs the privilege. Once "elevated", the application does not need to authenticate again until the application has been Quit and relaunched.

- However, there are varying levels of authentication, known as Rights. The right that is requested can be shown by expanding the triangle next to "details", underneath the password. Normally, applications use system.privilege.admin, but another may be used, such as a lower right for security, or a higher right if higher access is needed. If the right the application has is not suitable for a task, the application may need to authenticate again to increase the privilege level.

- PolicyKit can be configured to adopt either of these approaches.

Identifying when administrative rights are needed

In order for an operating system to know when to prompt the user for authorization, an application or action needs to identify itself as requiring elevated privileges. While it is technically possible for the user to be prompted at the exact moment that an operation requiring such privileges is executed, it is often not ideal to ask for privileges partway through completing a task. If the user were unable to provide proper credentials, the work done before requiring administrator privileges would have to be undone because the task could not be seen through to the end.

In the case of user interfaces such as the Control Panel in Microsoft Windows, and the Preferences panels in Mac OS X, the exact privilege requirements are hard-coded into the system so that the user is presented with an authorization dialog at an appropriate time (for example, before displaying information that only administrators should see). Different operating systems offer distinct methods for applications to identify their security requirements:

- sudo centralizes all privilege authorization information in a single configuration file,

/etc/sudoers, which contains a list of users and the privileged applications and actions that those users are permitted to use. The grammar of the sudoers file is intended to be flexible enough to cover many different scenarios, such as placing restrictions on command-line parameters. For example, a user can be granted access to change anybody's password except for the root account, as follows:

pete ALL = /usr/bin/passwd [A-z]*, !/usr/bin/passwd root

- User Account Control uses a combination of heuristic scanning and "application manifests" to determine if an application requires administrator privileges.[19] Manifest (.manifest) files, first introduced with Windows XP, are XML files with the same name as the application and a suffix of ".manifest", e.g.

Notepad.exe.manifest. When an application is started, the manifest is looked at for information about what security requirements the application has. For example, this XML fragment will indicate that the application will require administrator access, but will not require unfettered access to other parts of the user desktop outside the application:

<security>

<requestedPrivileges>

<requestedExecutionLevel level="requireAdministrator" uiAccess="false" />

</requestedPrivileges>

</security>

- Manifest files can also be compiled into the application executable itself as an embedded resource. Heuristic scanning is also used, primarily for backwards compatibility. One example of this is looking at the executable's file name; if it contains the word "Setup", it is assumed that the executable is an installer, and a UAC prompt is displayed before the application starts.[20]

- UAC also makes a distinction between elevation requests from a signed executable and an unsigned executable; and if the former, whether or not the publisher is 'Windows Vista'. The color, icon, and wording of the prompts are different in each case: for example, attempting to convey a greater sense of warning if the executable is unsigned than if not.[21]

- Applications using PolicyKit ask for specific privileges when prompting for authentication, and PolicyKit performs those actions on behalf of the application. Before authenticating, users are able to see which application requested the action and which action was requested.

See also

- Privilege escalation, a type of security exploit

- Principle of least privilege, a security design pattern

- Privileged Identity Management, the methodology of managing privileged accounts

- Privileged password management, similar concept to privileged identity management:

- i.e., periodically scramble privileged passwords; and

- store password values in a secure, highly available vault; and

- apply policy regarding when, how and to whom these passwords may be disclosed.

References

- "User Account Control Overview". Microsoft. 2006-10-02. Archived from the original on 2011-08-22. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- "Runas". Windows XP Product Documentation. Microsoft. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ""RunAs" basic (and intermediate) topics". Aaron Margosis' WebLog. MSDN Blogs. 2004-06-23. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- "About PolicyKit". PolicyKit Language Reference Manual. 2007. Archived from the original on 2012-02-18. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- Miller, Todd C. "A Brief History of Sudo". Archived from the original on 2007-02-22. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- Miller, Todd C. "Sudo in a Nutshell". Retrieved 2007-07-01.

- "GKSu home page".

- "gksu PolicyKit on Gnome wiki".

- Bellevue Linux (2004-11-20). "The KDE su Command". Archived from the original on 2007-02-02. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- Canonical Ltd. (2007-08-25). "GutsyGibbon/Tribe5/Kubuntu". Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- You can read more about beesu Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine and download it from Koji

- "gksu - a Gtk+ su frontend Linux Man Page". Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

- "User Account Control Prompts on the Secure Desktop". UACBlog. Microsoft. 2006-05-03. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- "gksu: locking mouse/keyboard not enough to protect against keylogging".

- "ptrace Protection".

- Allchin, Jim (2007-01-23). "Security Features vs. Convenience". Windows Vista Team Blog. Microsoft. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- "Authentication Agent". 2007. Archived from the original on 2012-02-18. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

- Miller, Todd C. "Sudoers Manual". Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- "Developer Best Practices and Guidelines for Applications in a Least Privileged Environment". MSDN. Microsoft. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- "Understanding and Configuring User Account Control in Windows Vista". TechNet. Microsoft. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- "Accessible UAC Prompts". Windows Vista Blog. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2008-01-27. Retrieved 2008-02-13.