Conference of Carnuntum

The Conference of Carnuntum (Latin: Carnuntum) was a military conference held on November 11, 308 in the city of Carnuntum (present-day Petronell-Carnuntum, Austria), which at the time was located in the province of Pannonia Prima. It was convened by the senior emperor of the East (Augustus) Galerius (r. 293-311) as a way to settle the dispute over the title of Augustus of the West and, consequently, to cease the ongoing conflicts since the previous year when he, and before that Severus II' (r. 305-307), invaded the Italy of Maxentius (r306-312) and Maximian (r. 286-308; 310). Present at the conference were Diocletian (r. 284-305), who had been retired since 305, and Maximian.

Ruins of Carnuntum | |

| Participants | Diocletian, Galerius, Maximian, Licinius |

|---|---|

| Location | Carnuntum, Austria, (ancient Panonnia Prima) |

| Date | November 11, 308 |

| Result | Inconclusive |

According to deliberations at the meeting, Maximian was to be permanently removed from his imperial position. Licinius (r. 308-324), a former general of Galerius, was appointed as Augustus of the West and was to deal with Maxentius, who had been treated as a usurper. Constantine the Great (r. 306-337) was demoted from his position of Augustus to Caesar. These decisions, however, did not please most monarchs, with Constantine questioning his demotion and Maximinus Daza (r. 305-313) demanding promotion. Moreover, Maximinus would not be satisfied with his demotion and would still attempt one last conspiracy at the Constantinian court in Gaul, while Licinius would do nothing in the following years to stop Maxentius.

Background

Since 293, the Roman Empire has been divided into two halves, each ruled by an Augustus (senior emperor) and a Caesar (junior emperor). On May 1, 305, the augusti Diocletian (r. 284-305) and Maximian (r. 285-308; 310) voluntarily abdicated and their Caesars Constantius Chlorus (r. 293-306) and Galerius (r. 293-311) were elevated to the western and eastern augustal position respectively,[1] while Severus II (r. 305-307) and Maximinus Daza (r. 305-313) would become Caesars of the West and East respectively.[2][3][4]

In 306, the Augustus of the West Constantius Chlorus (r. 293-306) died at Eboracum (present-day York, England),[5] and his soldiers elevated his son Constantine the Great (r. 306-337) as his successor.[6] The Augustus of the East Galerius (r. 293-311), however, elevates Severus II (r. 305-307) to the position of Augustus, since by the prerogatives of the prevailing Tetrarchy, being the western Caesar, he was to succeed the dead Augustus. After some diplomatic discussions, Galerius demoted Constantine to the position of Caesar, which he accepted, thus allowing Severus to assume his position.[7]

Maxentius (r. 306-312), son of Maximian (r. 285-308; 310), the Augustus predecessor of Constantius Chlorus, jealous of Constantine's position, declares himself emperor in Italy with the title of prince and calls his father out of retirement to co-govern with him. By 307, both suffer invasions by Valerius Severus, who is defeated and killed, and Galerius, who decides to withdraw.[7] In 308, likely in April, Maximian attempted to depose his son in a failed plot, forcing him to flee to Constantine's court in Gaul.[8] Aware of the situation in the West, Galerius decides to convene a conference, and Maximian pinned his hopes for ascension on it.[9]

Conference

On November 11, 308, Galerius convened the Conference of Carnuntum (now Petronell-Carnuntum, Austria) to try to stabilize the situation in the western provinces. Present at the conference were the retired emperor Diocletian, who briefly returned to public life, Galerius, and Maximian. At the conference, Maximian was forced to abdicate again and Constantine was demoted to his former position as Caesar.[7]

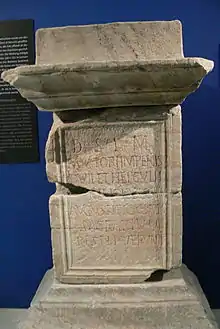

In addition, Licinius, one of Galerius' military companions who was attending the conference, was appointed Augustus of the West,[7] and was given the regions of Thrace, Pannonia, and Illyria, as well as the mission of neutralizing Maxentius in Italy.[10] Finally, the Augusti present rebuilt the Mithraeum of Carnuntum and dedicated it to the absent Caesars (Constantine and Maximinus Daza) and themselves:[11]

D(eo) S(oli) i(nvicto) M(ithrae) Fautori imperii sui Iovii et Herculii religiosissimi Augusti et Caesares Sacrarium restituerunt

For the scholar A. L. Frothingham, considering that by the fourth century the cult of Mitre and the Sol Invictus was on the rise, it is not surprising that a dedication was made to these gods in the name of the emperors. According to him, this could be interpreted as a symbolic handing over of the state to these gods, who from that moment on would have the mission to guard it and prevent it from returning to the Crisis of the Third Century.[12]

- Augustus

- Caesars

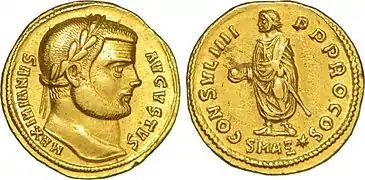

Solidus of Constantine the Great (r. 306-337) issued at Antioch ca. 324-325

Solidus of Constantine the Great (r. 306-337) issued at Antioch ca. 324-325

Consequences

The new system would not last long: Constantine the Great refused to accept his demotion and continued to portray himself as Augustus in his coinage, even though the other members of the Tetrarchy referred to him as Caesar. Licinius, therefore, did nothing to remove the usurper Maxentiustius from power and preferred to deal with internal problems and barbarian invasions in the provinces vested in him.[10] Thus, Maximinus Daza, became frustrated at being disregarded as a possible occupant of the position granted to Licinius, and demanded a promotion from Galerius. Galerius offered to call Maximinus and Constantine "sons of the Augusti" (Latin: filii Augustorum),[13][14][15][16][17][18][19] a title refused by both. By the spring of 310, however, both were called Augusti by Galerius.[20][21]

In 310, taking advantage of Constantine's absence, who was on the Rhine River frontier fighting against Frankish invaders, Maximian rebelled at Arelate (present-day Arles, France) and tried to take his position. He would gain little support for the revolt and soon Constantine would become aware of what had occurred. Constantine immediately headed south to Gaul and could easily quell the revolt, capturing him and encouraging him to commit suicide.[9][22][17][23][24][25][26] The following year, Magentius, calling for revenge for his father's death, declared war on Constantine, who responded with an invasion of northern Italy in 312.[27][28] In the same year, Galerius dies and the Eastern Roman Empire is divided between Maximinus Daia and Licinius who, after some disagreements, decide to sign peace in 312 on the Bosphorus. It would be short-lived, with them declaring war on each other by 313.[7][29]

See also

References

- Potter, D. S. (2004). The Roman Empire at bay : AD 180-395. London: Routledge. p. 342. ISBN 0-415-10057-7. OCLC 52430927.

- Barnes, Timothy David (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 25–27. ISBN 0-674-16530-6. OCLC 7459753.

- Williams, Stephen (1997). Diocletian and the Roman recovery (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 191. ISBN 0-415-91827-8. OCLC 35008231.

- Southern, Pat (2001). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. London: Routledge. p. 152. ISBN 0-415-23943-5. OCLC 46421874.

- "Constantius I Chlorus (305-306 A.D.) – Roman Emperors – An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and Their Families". Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- "Eutropius: Abridgement of Roman History". www.forumromanum.org. Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- "Galerius (305-311 A.D.) – Roman Emperors – An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and Their Families". Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- "Maxentius (306-312 A.D.) – Roman Emperors – An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and Their Families". Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- "Maximianus Herculius (286-305 A.D) – Roman Emperors – An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and Their Families". Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- "Roman Emperors – An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and Their Families". Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- Frothingham, A. L (1914). "Diocletian and Mithra in the Roman Forum". American Journal of Archaeology. 18 (2): 146–151.

- Frothingham, A. L. (1914). "Diocletian and Mithra in the Roman Forum". American Journal of Archaeology. 18 (2): 146–151.

- Elliott, T. G. (1996). The Christianity of Constantine the Great. Bronx, NY: Marketing and Distribution, Fordham University Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 0-585-02393-X. OCLC 42329037.

- Barnes, Timothy David (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 32–34. ISBN 0-674-16530-6. OCLC 7459753.

- The Cambridge companion to the Age of Constantine. Noel Emmanuel Lenski. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2006. p. 65. ISBN 0-521-81838-9. OCLC 59402008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Odahl, Charles Matson (2004). Constantine and the Christian empire. London: Routledge. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0-415-17485-6. OCLC 53434884.

- Pohlsander, Hans A. (2004). The Emperor Constantine (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-203-62258-2. OCLC 826515950.

- Pohlsander, Hans A. (2004). The Emperor Constantine (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 349–50. ISBN 978-0-203-62258-2. OCLC 826515950.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A history of the Byzantine state and society. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-8047-2421-0. OCLC 37154904.

- Jones, A. H. M. (1978). Constantine and the Conversion of Europe. Buffalo: University of Toronto Press. p. 61.

- Barnes, Timothy David (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0-674-16530-6. OCLC 7459753.

- Barnes, Timothy David (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-674-16530-6. OCLC 7459753.

- Elliott, T. G. (1996). The Christianity of Constantine the Great. Bronx, NY: Marketing and Distribution, Fordham University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-585-02393-X. OCLC 42329037.

- The Cambridge companion to the Age of Constantine. Noel Emmanuel Lenski. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2006. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-521-81838-9. OCLC 59402008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Odahl, Charles Matson (2004). Constantine and the Christian empire. London: Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 0-415-17485-6. OCLC 53434884.

- Potter, D. S. (2004). The Roman Empire at bay : AD 180-395. London: Routledge. p. 352. ISBN 0-415-10057-7. OCLC 52430927.

- Anonymous 3rd-4th century, (9)5.1–3.

- MacMullen, Ramsay (1987). Constantine. London: Croom Helm. p. 71. ISBN 0-7099-4685-6. OCLC 14717792.

- "Maximinus Daia (305-313 A.D.) – Roman Emperors – An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and Their Families". Retrieved 2022-11-15.