Ticino

Ticino (/tɪˈtʃiːnoʊ/), sometimes Tessin (/tɛˈsiːn, tɛˈsæ̃/), officially[3] the Republic and Canton of Ticino or less formally the Canton of Ticino,[lower-alpha 1] is one of the 26 cantons forming the Swiss Confederation. It is composed of eight districts and its capital city is Bellinzona. It is also traditionally divided into the Sopraceneri and the Sottoceneri, respectively north and south of Monte Ceneri. Red and blue are the colours of its flag.

Ticino | |

|---|---|

| Republic and Canton of Ticino Repubblica e Cantone Ticino (Italian) | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Location in Switzerland

Map of Ticino  | |

| Coordinates: 46°19′N 8°49′E | |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Capital | Bellinzona |

| Largest City | Lugano |

| Subdivisions | 115 municipalities, 8 districts |

| Government | |

| • Executive | Council of State (5) |

| • Legislative | Grand Council (90) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,812.21 km2 (1,085.80 sq mi) |

| Population (December 2020)[2] | |

| • Total | 350,986 |

| • Density | 120/km2 (320/sq mi) |

| ISO 3166 code | CH-TI |

| Highest point | 3,402 m (11,161 ft): Adula (Rheinwaldhorn) |

| Lowest point | 195 m (640 ft): Lake Maggiore |

| Joined | 1803 |

| Languages | Italian |

| Website | www |

Ticino is the southernmost canton of Switzerland. It is one of the three large southern Alpine cantons, along with Valais and the Grisons. However, unlike all other cantons, it lies almost entirely south of the Alps, and has no natural access to the Swiss Plateau. Through the main crest of the Gotthard and adjacent mountain ranges, it borders the canton of Valais to the northwest, the canton of Uri to the north and the canton of Grisons to the northeast; the latter canton being also the only one to share some borders with Ticino at the level of the plains. The canton shares international borders with Italy as well, including a small Italian enclave.

Named after the Ticino, its longest river, it is the only canton where Italian is the sole official language and represents the bulk of the Italian-speaking area of Switzerland along with the southern parts of the Grisons. In 2020, Ticino had a population of 350,986.[2] The largest city is Lugano, and the two other notable centres are Bellinzona and Locarno. While the geography of the Sopraceneri region is marked by the High Alps and Lake Maggiore, that of the Sottoceneri is marked by the Alpine foothills and Lake Lugano. The canton, which has become one of the major tourist destinations of Switzerland, distinguishes itself from the rest of the country by its warm climate, and its meridional culture and gastronomy.

The land now occupied by the canton was annexed from Italian cities in the 15th century by various Swiss forces in the last transalpine campaigns of the Old Swiss Confederacy. In the Helvetic Republic, established in 1798, it was divided between the two new cantons of Bellinzona and Lugano. The creation of the Swiss Confederation in 1803 saw these two cantons combine to form the modern canton of Ticino. Because of its unusual position, the canton relies on important infrastructure for connection with the rest of the country. The first major north–south railway link across the Alps, the Gotthard Railway, opened in 1882. In 2016, the Gotthard Base Tunnel was inaugurated, which finally provided a fully flat route through the Alps.

Etymology

The name Ticino was chosen for the newly established canton in 1803, after the river Ticino which flows through it from the Novena Pass to Lake Maggiore.[4]

Known as Ticinus in Roman times, the river appears on the Tabula Peutingeriana as Ticenum. Johann Kaspar Zeuss attributed Celtic origins to the name, tracing it to the Celtic tek, itself from an Indo-European root tak, meaning "melting, flowing".[5]

The official name of the canton is Republic and Canton of Ticino (Italian: Repubblica e Cantone Ticino), and the two-letter code is TI. It is one of the four cantons of Switzerland officially referred to as "republics", along with Geneva, Neuchâtel and Jura.

History

During the Bronze and Iron ages, the area of what is today Ticino was settled by the Lepontii, a Celtic tribe. Later, probably around the rule of Augustus, it became part of the Roman Empire. After the fall of the Western Empire, it was ruled by the Ostrogoths, the Lombards and the Franks. Around 1100 it was the centre of struggle between the free communes of Milan and Como: in the 14th century it was acquired by the Visconti, Dukes of Milan. In the fifteenth century the Swiss Confederates conquered the valleys south of the Alps in three separate conquests.

Between 1403 and 1422 some of these lands were already annexed by forces from the canton of Uri, but subsequently lost. Uri conquered the Leventina Valley in 1440.[6] In a second conquest Uri, Schwyz and Nidwalden gained the town of Bellinzona and the Riviera in 1500.[6] Some of the land and Bellinzona itself were previously annexed by Uri in 1419 but lost again in 1422. The third conquest was fought by troops from the entire Confederation (at that time constituted by 12 cantons). In 1512 Locarno, the Maggia Valley, Lugano and Mendrisio were annexed. Subsequently, the upper valley of the river Ticino, from the St. Gotthard to the town of Biasca (Leventina Valley) was part of Uri. The remaining territory (Baliaggi Ultramontani, Ennetbergische Vogteien, the Bailiwicks Beyond the Mountains) was administered by the Twelve Cantons. These districts were governed by bailiffs holding office for two years and purchasing it from the members of the League.[6]

The lands of the canton of Ticino are the last lands to be conquered by the Swiss Confederation. The Confederation gave up any further conquests after their defeat at the battle of Marignano in 1515 by Francis I of France. The Valle Leventina revolted unsuccessfully against Uri in 1755.[6] In February 1798 an attempt of annexation by the Cisalpine Republic was repelled by a volunteer militia in Lugano. Between 1798 and 1803, during the Helvetic Republic, two cantons were created (Bellinzona and Lugano) but in 1803 the two were unified to form the canton of Ticino that joined the Swiss Confederation as a full member in the same year under the Act of Mediation.[7] During the Napoleonic Wars, many Ticinesi (as was the case for other Swiss) served in Swiss military units allied with the French. The canton minted its own currency, the Ticinese franco, between 1813 and 1850, when it began use of the Swiss franc.

As a particularly poor region, Ticino was a land of emigration. Notable examples include the chocolatiers (cioccolatieri) of the Val Blenio, who migrated throughout Europe (see Swiss chocolate#History).[8][9]

Until 1878 the three largest cities, Bellinzona, Lugano and Locarno, alternated as capital of the canton. In 1878, however, Bellinzona became the only and permanent capital. The 1870–1891 period saw a surge of political turbulence in Ticino, and the authorities needed the assistance of the federal government to restore order in several instances, in 1870, 1876, 1889 and 1890–1891.[10]

The current cantonal constitution dates from 1997. The previous constitution, heavily modified, was codified in 1830, nearly 20 years before the constitution of the Swiss Confederation.[11]

Geography

.jpg.webp)

Ticino is the southernmost canton of Switzerland. With a few exceptions in the extreme north and south of the canton, it lies entirely in the Ticino basin, a tributary of the Po. Along with Valais and the Grisons, it is one of the three cantons whose territory comprehends the Po basin, therefore south of the Alps. However, contrary to those cantons (and all others), all settlements of Ticino are on the south side of the Alps, therefore separated from the Swiss Plateau (and most of the country) by the great Alpine barrier. The canton also comprehends some small areas in the Rhine basin in the north, at the Gotthard Pass and around lake of Santa Maria. The extreme south of the canton is drained by the Po as well, but through the Breggia and Adda,[13] and Gaggiolo, Olona, Lambro.

The canton is traditionally (but not administratively) split into two regions. The northern region, the Sopraceneri, is formed by the valleys around Lake Maggiore and includes the highest mountains of the canton and the main Alpine watershed. The southern region, the Sottoceneri, is the region around Lake Lugano, and marks the beginning of the southern Alpine foothills. Between the two regions is Monte Ceneri, a moderately elevated mountain pass and important north–south axis.[13] The Sopraceneri is constituted by the districts of Bellinzona, Blenio, Leventina, Locarno, Riviera and Vallemaggia, and makes up about 85% of the territory and 43% of the population.[14] The Sottoceneri is constituted by the districts of Lugano and Mendrisio, and makes up about 15% of the territory and 57% of the population.[15] While Lugano, the largest city, is in the densely populated Sottoceneri, the two other main cities, Bellinzona and Locarno, are in the Sopraceneri.

The Ticino, which gives its name to the canton, is the largest river of Ticino. It flows from the northwest through the Bedretto Valley and the Leventina Valley to enter Lake Maggiore near Locarno. Its main tributaries are the Brenno in the Blenio Valley and the Moesa in the Mesolcina Valley in the Grisons. The lands of most of the canton are shaped by the river, which in its mid portion forms a wide valley, commonly known as the Riviera. The western lands of the canton, however, are drained by the Maggia. The Verzasca Valley is between the Leventina Valley and the Maggia Valley. There is also a smaller area that drains directly into the Lake Lugano. Most of the land is considered within the Alps, but a small area is part of the plain of the Po which drains the north of Italy.

Although it includes the lowest point of Switzerland (Lake Maggiore) as well as its lowest town (Ascona), the topography of Ticino is extremely rugged, as it is the fourth canton with the biggest elevation difference. It lies essentially within the Alps, in particular the Lepontine Alps, the Saint-Gotthard Massif and the Lugano Prealps. The longest and deepest valleys are those of the Ticino, Verzasca and Maggia. The two highest mountains are the Rheinwaldhorn and the Basòdino. Other notable mountains are Pizzo Rotondo (highest of the Gotthard Massif), Pizzo Campo Tencia (highest fully within the canton), Monte Generoso (highest south of Lake Lugano) and Monte Tamaro (most prominent of the canton). For an exhaustive list, see list of mountains of Ticino.

The area of the canton is 2,812 square kilometres (1,086 sq mi), of which about three-quarters are considered productive to trees or crops.[16] Forests cover about a third of the area, but also the lakes Maggiore (or Verbano) and Lugano (or Ceresio) make up a considerable minority. The canton shares borders with three other cantons across the main ridge of the Alps: Valais to the northwest, to which it is connected by the Nufenen Pass, Uri to the north, to which it is connected by the Gotthard Pass and the Grisons to the northeast, to which it is connected by the Lukmanier Pass and the Mesolcina Valley; the latter valley, a few kilometres north of Bellinzona, being the only (natural) low elevation access to another canton. Ticino shares international borders with Italy as well. To the southwest is the region of Piedmont and to the southeast is the region of Lombardy. The main border crossing between Italy and Switzerland is that of Chiasso, in the extreme south of the canton.[13]

Climate

The climate of Ticino is mostly influenced by the Mediterranean Sea, the Alps protecting it from north European weather.[17][18] As a consequence, the plains experience warm and moist summers, and mild winters. This climate is noticeably warmer and wetter than the rest of Switzerland's. In German-speaking Switzerland, Ticino is nicknamed Sonnenstube (sun porch), owing to the more than 2,300 sunshine hours the canton receives every year, compared to 1,700 for Zurich.[19] The canton can experience particularly heavy storms and rainfalls in summer. It is the region of Switzerland with the highest level of lightning discharge.[20] Conversely, the canton can experience severe droughts in both summer and winter, making it the region most affected by forest fires in the country.[21]

The climate of Ticino is highly diverse as elevations range from Lake Maggiore, affected by subtropical climate, to the high Alps, affected by subarctic and tundra climate.[22][23] Therefore, similarly to the rest of Switzerland, many different types of ecosystems are found in the region. In the lower areas, deciduous forests are omnipresent, while at high elevations they tend to be replaced by coniferous forests, except in the Sottoceneri (Lugano Prealps), where they are almost absent. The treeline is located at around 2,000 metres in the Sopraceneri and 1,600 metres in the Sottoceneri.[24] The Basòdino, Ticino's second-highest mountain, is covered by the largest glacier of the canton. In winter, skiing is popular in the highest locations, notably in Airolo and Bosco/Gurin. In the lower regions, especially around Lake Maggiore and Lake Lugano, vineyards, olive trees[25] and other fruits common to southern Europe are grown.[26] Several types of cold hardy palm trees and other subtropical species may be grown here, and although none are native, their presence in the ecosystem is increasing.[27] Numerous gardens, especially near the lakes, such as the Brissago Islands and the Scherrer Park, are renowned for their exotic plants.

Diocese

The Diocese of Lugano is co-extensive to the canton.

Wine region

Ticino is one of the wine regions for Swiss wine. The defined region encompasses all of the canton plus the neighbouring Italian-speaking district of Moesa (Misox and Calanca valleys) in the canton of the Grisons.

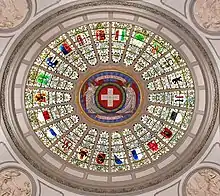

Government

The current Constitution of the Republic and Canton of Ticino, originating from a draft approved on 18 August 1801 during the Helvetic Republic,[28] was approved on 14 December 1997.[29] In its preamble, it states that it was created by the Ticinese people (popolo) "in order to guaranty peaceful life together with respect for the dignity of man, fundamental liberties and social justice (...) faithful to its historic task to interpret Italian culture within the Helvetic Confederation".[29]

The Grand Council (Gran Consiglio) is the legislative authority of the canton, exercising sovereignty over any matter not explicitly delegated by the constitution to another authority.[29] The Gran Consiglio has 90 members called deputati (deputies), elected in a single constituency using the proportional representation system.[29] Deputies serve four-year terms, and annually nominate a President and two vice-presidents.

The five-member Council of State (Italian: Consiglio di Stato), not to be confused with the federal Council of States, is the executive authority of the canton, and it directs cantonal affairs according to law and the constitution. It is elected in a single constituency using the proportional representation system. Currently, the five members of the Government are: Claudio Zali, Raffaele De Rosa, Manuele Bertoli, Norman Gobbi and Christian Vitta.

Each year, the Council of State nominates its president.[29] The current president of the Council of State is Norman Gobbi.[30]

The most recent elections were held in April 2019; the next elections will be on 2 April 2023.[31]

The cantonal capital is Bellinzona. The Palazzo delle Orsoline on Piazza Governo is the meeting place for both the Grand Council and the Council of State.[29] Nearby Piazza Governo is Piazza Indipendenza, which commemorates the independence of the canton.

Politics

Federal election results

| Percentage of the total vote per party in the canton in the National Council Elections 1971–2019[32][33] | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Ideology | 1971 | 1975 | 1979 | 1983 | 1987 | 1991 | 1995 | 1999 | 2003 | 2007 | 2011 | 2015 | 2019 | |

| FDP.The Liberalsa | Classical liberalism | 38.4 | 39.1 | 36.3 | 37.9 | 34.8 | 29.4 | 30.5 | 27.7 | 29.8 | 28.1 | 24.8 | 23.7 | 20.5 | |

| CVP/PDC/PPD/PCD | Christian democracy | 34.8 | 35.7 | 34.1 | 34.0 | 38.2 | 26.9 | 28.4 | 25.9 | 24.6 | 24.1 | 20.0 | 20.1 | 18.2 | |

| SP/PS | Social democracy | 13.1 | 13.9 | 15.2 | 13.8 | 9.3 | 6.7 | 17.1 | 18.8 | 25.8 | 18.1 | 16.6 | 15.9 | 14.1 | |

| SVP/UDC | Conservatism | 2.4 | * b | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 5.3 | 7.6 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 11.3 | 11.7 | |

| EVP/PEV | Christian democracy | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0.2 | * | * | * | * | * | |

| GLP/PVL | Green liberalism | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0.8 | 1.0 | |

| PdA/PST-POP/PC/PSL | Socialism | 2.8 | 3.6 | 2.7 | * | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 1.3 | * | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | |

| PSA | Socialism | 6.7 | 7.6 | 9.4 | 10.6 | 11.0 | 10.0 | c | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| GPS/PES | Green politics | * | * | * | * | 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 3.5 | 12.1 | |

| FGA | Feminist | * | * | * | * | 0.9 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| SD/DS | National conservatism | 1.8 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Ticino League | Right-wing populism | * | * | * | * | * | 23.5 | 18.6 | 18.5 | 8.0 | 14.0 | 17.5 | 21.7 | 16.9 | |

| Other | * | 0.2 | * | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 4.7 | ||

| Voter participation % | 60.6 | 64.7 | 59.6 | 61.6 | 60.2 | 67.5 | 52.8 | 49.7 | 48.6 | 47.4 | 54.3 | 54.4 | 49.8 | ||

Referendum decisions

Since a referendum in September 2013, Ticino is the only Swiss canton where wearing full-face veils is illegal.[34] Supporters of the ban cited the case of a 20-year-old Pakistani woman from Bellinzona, who was killed by her husband for refusing to wear a headscarf.[35][36] The Burqa ban was later approved by the Grand Council in November 2015.[37]

In September 2016, Ticino voters approved a Swiss People's Party-sponsored referendum that gives precedence to Swiss workers, as opposed to foreign workers, defying freedom of movement agreements between Switzerland and the EU.[38][39]

Political subdivisions

Districts

The canton is divided into eight districts:[40]

- Bellinzona with capital Bellinzona

- Blenio with capital Acquarossa

- Leventina with capital Faido

- Locarno with capital Locarno

- Lugano with capital Lugano

- Mendrisio with capital Mendrisio

- Riviera with capital Osogna

- Vallemaggia with capital Cevio

History of the districts

Leventina was a subject of the canton of Uri until 1798, the year the Helvetic Republic was founded, when it became part of the new canton of Bellinzona along with the Swiss condominiums of Bellinzona, Riviera and Blenio. The condominiums of Locarno, Lugano, Mendrisio and Vallemaggia became part of the new canton of Lugano in 1798. These two cantons formed into one canton, Ticino, in 1803 when it joined the (restored) Swiss Confederation as a member canton. The former condominiums and Leventina became the eight districts of the canton of Ticino, which exist to the present day and are provided for by the cantonal constitution.

Municipalities and circles

There are 108 municipalities in the canton (as of June 2021). These municipalities (comuni) are grouped in 38 circoli (circles or sub-districts) which are in turn grouped into the eight districts (distretti).[41]

The mayor (sindaco) is the president of the municipal government (municipio) which comprises at least three members; a council also exists. The members of the council and the municipio are elected every four years by the citizens resident in the comune – the next elections are scheduled for April 2024.[31]

Since the late 1990s there is an ongoing project to aggregate some municipalities, with the constitution of the canton allowing for the Grand Council of Ticino to promote and lead in deciding on mergers.[40] This has resulted in changes to some of the circles, with many circles now consisting of just one or two municipalities. The most populous municipality – Lugano (having merged with numerous other municipalities) – is subdivided into quartieri (quarters) which are grouped into three (cantonal) circles. In the modern day, the circle serves only as a territorial unit with limited public functions, most notably the local judiciary.

Demographics

Religion in canton of Ticino (age 15+, 2012)[42]

Ticino has a population (as of 31 December 2020) of 350,986.[2] As of 2013, the population included 94,366 foreigners, or about 27.2% of the total population. The largest groups of foreign population were Italians (46.2%), followed by Croats (6.5%) and the Portuguese (5.9%).[42] The population density (in 2005) is 114.6 persons per km2.[16] As of 2000, 83.1% of the population spoke Italian, 8.3% spoke German and 1.7% spoke Serbo-Croatian.[16]

As of 2019, 70.0% of the total population was Catholic.[43] According to a 2012 survey, the population aged 15 years and older was mostly Catholic (70%); further Christian denominations accounted for 10% of the population (including Swiss Reformed 4%), 2% were Muslim and 1% of the population adhered to another religion (including Jews 0.1%).[42]

The official language, and the one used for most written communication, is Swiss Italian. Despite being very similar to standard Italian, Swiss Italian presents some differences to the Italian spoken in Italy due to the influence of French and German from which it assimilates words. Dialects of the Lombard language such as Ticinese are still spoken, especially in the valleys, but they are not used for official purposes.

Despite the dominance of Italian speakers, fluency in Standard or Swiss German is sometimes taken to be an important prerequisite for employment, regardless of sector or sphere of work.[44]

In 2016, Ticino was the European region with the second highest life expectancy at 85.0 years, and highest male life expectancy at 82.7 years.[45]

Historical population

The historical population is given in the following table:

| Historic Population Data[46] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total Population | Swiss | Non-Swiss | Population share of total country |

| 1850 | 117 759 | 109,952 | 7,807 | 4.9% |

| 1880 | 130,394 | 110,306 | 20,088 | 4.6% |

| 1900 | 138,638 | 108,181 | 30,457 | 4.2% |

| 1950 | 175,055 | 144,909 | 30,146 | 3.7% |

| 1970 | 245,458 | 177,954 | 67,504 | 3.9% |

| 2000 | 306,846 | 228,057 | 78,789 | 4.2% |

| 2020 | 350,986 | 4.1% | ||

Economy

Tertiary sector workers make up 76.5% of the Ticinese workforce, compared to the Swiss average of 67.1%. Commerce (23.1%), tourism (10.1%) and financial activities (3.9%) are all important for the local economy, while the contribution from agriculture and fishing is marginal, employing 6.5% of the workforce on a Swiss average of 15.4%.[47] The median gross private sector monthly salary in 2012 was 5,091 francs (US$5,580), below the national average of 6,118 francs (US$6,703). [48] However, due to lesser cost of living and lower taxation compared to most other cantons, the overall disposable mean income is high.[49] The GDP per capita at 82,438 francs in 2014, was seventh highest in Switzerland.[50] Ticino is counted among the most prosperous regions of Switzerland and of Europe.[51]

Lugano is Switzerland's third largest financial center after Zurich and Geneva.[52] The banking industry alone has 8,400 employees and generates 17% of the gross cantonal product.[53] Because of Ticino's shared language and culture, its financial industry has very close ties to Italy.[53] In 2017, Ticino had an unemployment rate of 4%, higher than the Switzerland average where it was estimated at 3.7%.[54]

Frontalieri, commuter workers living in Italy (mostly in the provinces of Varese and Como) but working regularly in Ticino, form a large part (over 20%) of the workforce, far larger than in the rest of Switzerland, where the rate is below 5%. Foreigners in general hold 44.3% of all the jobs, again a much higher rate than elsewhere in the Confederation (27%).[55] Frontalieri are usually paid less than Swiss workers for their jobs, and tend to serve as low-cost labour.[56]

Italy is by far Ticino's most important foreign trading partner, but there's a huge trade deficit between imports (5 billion CHF) and exports (1.9 billion).[57] By 2013, Germany had become the canton's main export market, receiving 23.1% of the total, compared to 15.8% for Italy and 9.9% for the United States.[58] Many Italian companies relocate to Ticino, either temporarily or permanently, seeking lower taxes and an efficient bureaucracy:[59] just as many Ticinese entrepreneurs doing business in Italy complain of red tape and widespread protectionism.[60] The region has been attracting multinational companies particularly from the fashion industry due to its closeness to Milan. Hugo Boss, Gucci, VF Corporation and other popular brands are located there. Because the international fashion business has become a significant employer for Swiss and Italians alike, the region has also been termed the "Fashion Valley".[61]

Three of the world's largest gold refineries are based in Ticino,[62] including the Pamp refinery in Castel San Pietro, the leading manufacturer of minted gold bars.[63] Large companies based in the canton include: Bally, Hupac.

The opening of the Gotthard Railway in 1882 led to the establishment of a sizeable tourist industry mostly catering to German-speakers,[64] although since the early 2000s the industry has suffered from the competition of more distant destinations. In 2011, 1,728,888 overnight stays were recorded.[65] The mild climate throughout the year makes the canton a popular destination for hikers.[66] The high Alps of Ticino include numerous tourist facilities such as the Monte Generoso Railway, the Ritom Funicular and the Cardada Cableway. Among other tourist attractions are the Verzasca Dam, popular with bungee jumpers,[66] and Swissminiatur in Melide, a miniature park featuring scale models of over 120 Swiss monuments.[67] The Brissago Islands on Lake Maggiore are the only Swiss islands south of the Alps, and house botanical gardens with 1,600 different plant species from five continents.[68]

Transport

.jpg.webp)

The Gotthard is a strategic mountain pass of Central Switzerland and Ticino since the 13th century. Several tunnels underneath the Gotthard connect the canton to northern Switzerland: the first to open was the 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) long Gotthard Rail Tunnel in 1882, replacing the pass road, connecting Airolo with Göschenen in the canton of Uri.[69] A 17 km (11 mi) motorway tunnel, the Gotthard Road Tunnel, opened in 1980.[70] A second rail tunnel through the pass, the Gotthard Base Tunnel, was opened on 1 June 2016. The new tunnel is the longest tunnel in the world,[71] reducing travel time between Zürich and Lugano to 1 hour 40 minutes.[71] It is the first flat route through the Alps and provides for the first time a low-level route to the cities of the Swiss Plateau.

The Ceneri Base Tunnel, inaugurated in 2020, constitutes another revolution in the canton, by providing fast links to both Locarno and Bellinzona from Lugano, and making the latter city an important railway node. The base tunnel bypasses the old Monte Ceneri axis.

Treni Regionali Ticino Lombardia (TiLo), a joint venture between the Italian Ferrovie dello Stato and the Swiss Federal Railways launched in 2004, manages the traffic between the regional railways of Lombardy and the Ticino railway network via a S-Bahn system.[72] The canton is also served by the Treno Gottardo from northern Switzerland, operated by the Südostbahn (SOB).

The Regional Bus and Rail Company of Ticino provides the urban and suburban bus network of Locarno, operates the cable cars between Verdasio and Rasa, and between Intragna – Pila – Costa on behalf of the owning companies, and, together with an Italian company, the Centovalli and Vigezzina Railway which connects the Gotthard trans-Alpine rail route at Locarno with the Simplon trans-Alpine route at Domodossola, with further connections with Brig in Valais.

The canton has a higher than average incidence of traffic accidents, recording 16 deaths or serious injuries per 100 million km in the 2004–2006 period, compared to a Swiss average of 6.[73]

Lugano Airport is the busiest airport in south east Switzerland, serving some 200,000 passengers a year.[74]

Education and science

There are two major centres of education and research located in the canton of Ticino. University of Italian Switzerland (USI, Università della Svizzera Italiana) in Lugano is the only Swiss university teaching primarily in Italian. The University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland (SUPSI, Scuola Universitaria Professionale della Svizzera Italiana), in Manno, is a professional training college focused on a practical method of teaching in the areas of applied art, economy, social work, technology and production science.[53]

There is also a small American and Swiss accredited private college, Franklin University Switzerland, located above Lugano,[75] as well as The American School in Switzerland in Collina d'Oro, a K-13 international school accepting day and boarding students.

Following Google Scholar, several scientists working in Ticino have received more than 100,000 scientific citations and have an h-index greater than 100, for example, Michele Parrinello in chemistry (Profile), Jürgen Schmidhuber in artificial intelligence (Profile), and Antonio Lanzavecchia in immunology (Profile).

Culture

As the only predominantly Italian-speaking canton, Ticino notably distinguishes itself from the rest of the country by its meridional, or Mediterranean, culture.[76] Cultural identity of Ticino is complex and is marked by its long history as a bailiwick of the Swiss Confederacy, until its independence of 1803.[77] Ticinese identity was gradually forged in the 19th century, partly thanks to the efforts of major intellectual figures such as Stefano Franscini and Carlo Cattaneo.[78] Cantonal patriotism is particularly strong in Ticino; this is reflected by the use of the term repubblica in official documents.[79][80]

Ticino is particularly known for its rich architectural heritage, ranging from the anonymous rock architecture of grottos and splüi, over Romanesque and baroque to contemporary styles. The birthplace of Francesco Borromini, the canton is home to internationally recognized architects, such as Mario Botta, Aurelio Galfetti, Luigi Snozzi, and Livio Vacchini.[81] As early as the 18th century, aristocrats from Russia and Italy employed numerous architects from Ticino.[82] More recently, the region became a centre of the Neo-Rationalist Tendenza movement.[83]

.jpg.webp)

Ticino hosts two World Heritage Sites: the Three Castles of Bellinzona and Monte San Giorgio.[81] The city of Locarno is host to the Locarno International Film Festival, Switzerland's most prestigious film festival, held during the second week of August.[84] Estival Jazz, a free open-air jazz festival, is held in Lugano and Mendrisio in late June and July.[85][86] Another jazz festival is held in Ascona. Rabadan is the major carnival festival of the canton. It has been ongoing now for more than 150 years.[87]

Traditional folk music of Ticino also distinguishes itself from that of northern Switzerland.[88] Among traditional instruments are the accordion, the guitar and, since the 19th century, the mandolin. Duos and trios with mandolin and guitar typically accompany regional folk songs.[89] However, like most of Switzerland, Ticino has a long brass-band tradition. A regional, reduced version, is the bandella, an ensemble consisting of brass instruments and clarinets.[90]

Polenta, along with chestnuts and potatoes, was for centuries one of the staple foods in Ticino, and it remains a mainstay of local cuisine.[91] Nowadays, the most typical dishes are polenta, often served with meat (such as rabbit) and gravy sauce, and risotto, often with saffron.[92] Local products of Ticino, called Nostrani, include a large variety of cheeses, meat specialities such as salami and prosciutto,[93] and wines, especially red merlot. Olive oil is produced in small quantities but olive cultivation is growing in the canton.[94] Sweet products of Ticino notably include the Torta di Pane, a cake made with stale bread softened in milk and containing dried and candied fruits,[95] and Panettone, a yeast-leavened bread containing candied fruits.[96][97] Gazzosa ticinese, a soft drink available in lemon and a number of other flavours, is one of the most popular beverages from Ticino, and is also common in other regions of Switzerland. It usually comes in flip-top bottles.[98] The estimate for the production of gazzosa in Ticino is 7–8 million bottles a year.[99] Food and wine were historically conserved in grottos, which were ubiquitous stone structures built in shadowy and fresh areas. They have become rustic, family-run open-air restaurants in the latter part of the 20th century. They serve traditional food and local wine (usually Merlot or similar), often in a little ceramic jug known as boccalino, which is also a popular souvenir for tourists.[100]

Newspapers and magazines published in Ticino include Corriere del Ticino, LaRegione Ticino, Giornale del Popolo, Il Mattino della Domenica, Il Caffè, L'Informatore, and the German-language Tessiner Zeitung.[101][102] In Lugano is based Radiotelevisione svizzera (RSI), a radio and television broadcasting branch of the national Swiss Broadcasting Corporation.

Bocce is a folk game that was once a popular pastime locally, but by the early 21st century it was seldom played by younger people.[103] Notable sports teams include HC Lugano, HC Ambrì-Piotta (ice hockey), FC Lugano (association football) and Lugano Tigers (basketball). Lugano has hosted the Italy-Belgium match at the 1954 FIFA World Cup, the 1953 and 1996 UCI Road World Championships, the 18th Chess Olympiad, and the annual BSI Challenger Lugano tennis tournament and Gran Premio Città di Lugano Memorial Albisetti 20 km racewalk.

Notable people

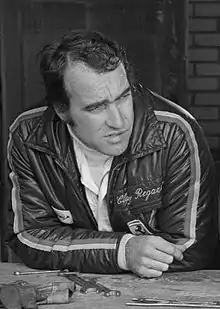

.jpg.webp)

- The Bernasconi family of stuccoists, architects and sculptors

- Francesco Borromini (1599 in Bissone – 1667), architect

- Mario Botta (born 1943 in Mendrisio) a Swiss architect.

- Ignazio Cassis (born 1961 in Sessa) a Swiss physician and politician, President of the Swiss Confederation for 2022.

- Flavio Cotti (1939 in Muralto – 2020) a Swiss politician, on the Federal Council, 1986 to 1999.

- Carla Del Ponte (born 1947 in Bignasco), international jurist

- Carlo Fontana (ca.1634–1714) & Domenico Fontana (1543–1607), architects

- Aurelio Galfetti (1936 in Biasca – 2021) a Swiss architect.

- Lara Gut-Behrami (born 1991 in Sorengo), ski racer, gold medallist at the 2022 Winter Olympics

- Carlo Maderno (1556 in Capolago – 1629), architect

- Giovanni Pietro Magni (1655 in Bruzella – ca.1722), stuccoist.[104]

- Clay Regazzoni (1939 in Mendrisio – 2006) a Swiss Formula One racing driver.

- Flora Ruchat-Roncati (1937–2012), architect

- Elly Schlein (born 1985 in Lugano), Italian politician and leader of the Democratic Party.

- Luigi Snozzi (1932 in Mendrisio – 2020), architect

- Livio Vacchini (1933 in Locarno – 2007), architect

Notes

References

- Arealstatistik Land Cover - Kantone und Grossregionen nach 6 Hauptbereichen accessed 27 October 2017

- "Ständige und nichtständige Wohnbevölkerung nach institutionellen Gliederungen, Geburtsort und Staatsangehörigkeit". bfs.admin.ch (in German). Swiss Federal Statistical Office - STAT-TAB. 31 December 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- Il Ticino in breve, ti.ch (official website of the canton). Retrieved 2021-01-25. ("Ticino is officially called the Republic and Canton of Ticino, its official language is Italian and its capital is Bellinzona")

- "Lo scorrere del fiume, l'opera dell'uomo". Azienda elettrica ticinese. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- Roberto Rampoldi (1901). "Intorno all'origine e al significato del nome Ticino". Internet Archive. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- Coolidge 1911, p. 934.

- Coolidge 1911, p. 933.

- Luigi, Lorenzetti (2007). "Emigrazione, imprenditorialità e rischi : i cioccolatieri bleniesi (XVIII-XIX secc.". Il cioccolato. Industria, mercato e società in Italia e Svizzera (XVIII-XX sec.). FrancoAngeli. pp. 39–52).

- Ainardi, Mauro Silvio (2008). Le fabbriche da cioccolata: nascita e sviluppo di un'industria lungo i canali di Torino. Umberto Allemandi. p. 51. ISBN 9788842215639.

Dall'elenco dei nominativi emerge come la produzione artigianale della cioccolata a Torino, nei primi decenni del XIX secolo, sia appannaggio di alcune famiglie originarie del Canton Ticino

[From the list of names it emerges how the artisanal production of chocolate in Turin, in the first decades of the 19th century, was the prerogative of some families originating from the Canton of Ticino] - Goldstein, Leslie Friedman (21 August 2001). Constituting Federal Sovereignty: The European Union in Comparative Context. JHU Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780801866630 – via Internet Archive.

- "The Constitution of Ticino". Ti.ch. Archived from the original on 19 May 2006. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- "Mergoscia - Corippo". Agenzia turistica ticinese. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

Da Mergoscia, centro geografico del Ticino, seguendo il sentiero sopra il lago di Vogorno fino a Corippo.

- "Ticino on the Swiss National Map". Federal Office of Topography. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- "Sopraceneri". Historical Dictionary of Switzerland. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

Il S. comprende i distr. di Bellinzona, Riviera, Blenio, Leventina, Locarno e Vallemaggia, che si estendono su ca. 2379 km2, pari all'85% ca. del territorio cant., e contano 142'627 ab. (2008), ossia il 43% della pop. ticinese.

- "Sottoceneri". Historical Dictionary of Switzerland. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

Costituito dagli attuali distr. di Lugano e Mendrisio, il S., di ca. 432 km2 di estensione e con 189'123 ab. (2008), comprende ca. il 15% del territorio cant., ma il 57% della pop. ed è quindi caratterizzato da una densità demografica già nel passato piuttosto elevata (oltre 100 ab. per km2 nel 1808).

- Federal Department of Statistics (2008). "Regional Statistics for Ticino". Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- Lucy J. Sheppard (2013). Forest Growth Responses to the Pollution Climate of the 21st Century. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 9789401715782.

The Ticino region situated to the south of the Swiss Alps generally experiences a Mediterranean climate, with hot but relatively moist summer seasons. The Alps form an arc around the plain of the Po valley, acting as a barrier against central European weather

- P. Lionello (2006). Mediterranean Climate Variability. Elsevier. p. 346. ISBN 9780080460796.

The heaviest rain events take place when the cyclone path is in such a position that it produces the local convergence of moist Mediterranean air. In the Western Mediterranean, this feeding flow is southerly for northern Italy and Ticino

- Jürg Steiner; Manuschak Karnusian; Omar Gisler (28 March 2014). MARCO POLO Reiseführer Tessin. Mair Dumont Marco Polo. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-8297-7172-6.

- "Luganese fulminato, bersaglio prediletto di Zeus". Swissinfo. 7 August 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

I dati raccolti da MeteoSvizzera sono impressionanti: nel 2008 in un raggio di trenta chilometri attorno a Lugano, sono stati registrati più di 13 mila fulmini, mentre in località analoghe come quota a nord delle Alpi, ne sono stati registrati fra 3 mila e 6 mila.

[The data collected by MeteoSwiss are impressive: in 2008 in a radius of thirty kilometers around Lugano, more than 13,000 lightning strikes were recorded, while in locations north of the Alps with a similar elevation, between 3,000 and 6,000 were recorded.] - M. Masellis (2012). The Management of Burns and Fire Disasters: Perspectives 2000. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 520. ISBN 9789400903616.

The Ticino is the canton most affected by forest fires in all Switzerland. Its geographical position at the southern foot of the Alps determines a climate that is extremely favourable to the development and spread of forest fires.

- "Isole di Brissago - Bosco Gurin". Agenzia turistica ticinese SA. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

The Trekking dei fiori, a new 5-day experience within the local nature and culture, spans the entire region of the Locarnese National Park Project, going from a subtropical climate to the alpine climate.

- Reynard, Emmanuel (2020). Landscapes and Landforms of Switzerland. Springer Nature. p. 325. ISBN 9783030432034.

For its geographical location and its particular morphological configurations, the Upper Ticino is located between the harsh Alpine climate and the more temperate Mediterranean climate.

- Christiane M. A. De Micheli Schulthess (2001). Aspects of Roman Pottery in Canton Ticino (Switzerland) (PDF) (PhD). University of Nottingham.

In the alpine region (Sopraceneri) the upper limit of the forests reaches 1900-2000m asl. This limit reaches 1600m asl in the subalpine region (Sottoceneri), characterized by the almost exclusive presence of hardwood forests.

- Irene, Solari (16 October 2021). "Alla scoperta dell'olio ticinese: "Un patrimonio di cui dovremmo essere fieri"". Corriere del Ticino. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

Il mese scorso l'olio d'oliva ticinese è stato inserito nel patrimonio culinario svizzero, annoverato tra i prodotti d'eccellenza del nostro Paese.

[Last month, Ticino olive oil was included in the Swiss culinary heritage, counted among the products of excellence of our country.] - James Redfern (1971). A Lexical Study of Raeto-Romance and Contiguous Italian Dialect Areas. Mouton Publishers. p. 38. ISBN 9783110824841.

The canton of the Ticino marks the geographic descent from high Alps to plain and is, therefore, a land of climatic as well as linguistic transition, where heat and abundant moisture favor almonds, figs, and all the fruits common to southern Europe, except the olive.

- Palm trees go wild in Ticino, Swissinfo, February 15, 2001 ("Palm trees and other exotic species have become so common in the forests of Switzerland's southern canton of Ticino they must now be considered as "native".")

- "Il Canton Ticino si appresta a festeggiare i suoi 200 anni" (in Italian). swissinfo. 20 August 2001. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- "Constitution of the Republic and Canton of Ticino" (in Italian). Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation. 14 December 1997. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- "Consiglio di Stato - CDS - Cantone Ticino". Archived from the original on 29 August 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- "Ecco le date delle elezioni cantonali 2023 e delle comunali 2024". www.cdt.ch (in Italian). 1 October 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- Nationalratswahlen: Stärke der Parteien nach Kantonen (Schweiz = 100%) (Report). Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- "Wahlen 2019 - Kanton Tessin: laufend aktualisierte Ergebnisse". www.elections.admin.ch. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Squires, Nick. "Burkas and niqabs banned from Swiss canton". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- "Swiss charge Pakistani over 'honour killing' of wife". Daily Times. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- Giorgio Ghiringhelli. "Divieto di indossare negli spazi pubblici e nei luoghi privati aperti al pubblico indumenti che nascondano totalmente o parzialmente il volto (ad esempio il burqa e il niqab)" (PDF). Corriere del Ticino. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- "MPs in Swiss canton of Ticino Back Burqa Ban". The Local. 24 November 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "Ticino Votes to Favour Local Workers Over Foreigners". The Local. 26 September 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Atkins, Ralph (25 September 2016). "Swiss Canton Votes for Tougher Controls on Foreign Workers". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "RS 131.229 Costituzione della Repubblica e Cantone Ticino, del 14 dicembre 1997". Admin.ch. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "CAN – Raccolta delle leggi del Cantone Ticino". www3.ti.ch.

- "Annuario Statistico Ticinese 2015" (in Italian). Ufficio di Statistica del Cantone Ticino. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Diocese of Lugano – Statistics". Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- Mackey, William; Ornstein, Jacob (22 July 2011). Sociolinguistic Studies in Language Contact: Methods and Cases. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110810752 – via Google Books.

- "Eurostat-Life expectancy at birth by sex and NUTS 2 region". Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- "Tessin (Kanton)". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (in German). Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- "Aziende per settore e sezione di attività economica" (PDF) (in Italian). Ufficio di statistica. 15 January 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Monatlicher Bruttolohn nach Grossregionen – Privater Sektor – Schweiz". Bundesamt für Statistik. Retrieved 14 November 2014. (exchange rate of 0.9126 on 31 December 2012)

- "Survey pinpoints least expensive places to live". Swissinfo.ch. 13 December 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "Cantonal gross domestic product (GDP) per capita – 2008–2014 | Table". Federal Statistical Office. 28 October 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "6 Swiss regions in Europe's 10 most prosperous". Lenews.ch. 12 May 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Povoledo, Elisabetta (13 October 2010). "Far Right Party's Ad Campaign Draws Criticism in Switzerland". NYTimes.com. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Ticino". United States Commercial Service. 14 March 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- "Swiss unemployment rises. French-speaking cantons worst affected". Lenews.ch. 15 February 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "Occupati stranieri e frontalieri" (PDF) (in Italian). Ufficio di statistica. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- Frontalieri in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- "Commercio estero" (PDF). Ufficio di statistica. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Esportazioni secondo il paese di destinazione, dal Ticino, dal 2006". USTAT. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- "Seicento ditte italiane in fuga verso il Ticino" (in Italian). Il caffè. 5 July 2009. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "In Italia c'è ancora troppa burocrazia" (in Italian). Il Caffè. 5 July 2009. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- N. Rütti & A. Ramp (May 2017). "Zwischen dem Tessin und Italien – Nirgendwo in Mitteleuropa zeigt sich deutlicher, was der Wegfall von Grenzen bedeutet" (in German). Neue Zürcher Zeitung (Wirtschaft). Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- "Gold refineries – another Swiss money-spinner". BBC News. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "La Pamp SA si espande in India". CdT.ch. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Die Sonnenstube der Schweiz: "Das Paradies ist hier!"". NZZ.ch. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- "Tessiner Tourismuszahlen: Im Allzeittief". NZZ.ch. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- "Ticino's warmer climate attracts hikers year-round". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- Nicola Williams; Damien Simonis; Kerry Walker (2009). Switzerland. Lonely Planet. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-74220-381-2.

- "Floral paradise blossoms on Brissago islands". swissinfo.ch. 10 June 2003. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- Hans-Peter Bärtschi: Gotthardbahn in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 29 July 2004.

- Gotthard Pass – The traffics from the late 19th century to the present in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- "Alp Transit 2016: verso nuovi equilibri territoriali" (PDF) (in Italian). Portal of canton of Ticino. 20 October 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Tilo: un primo bilancio positivo" (PDF). Portal of canton of Ticino. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Regional differences in traffic accidents – bfu-report no. 62 – bfu_2.041.08_bfu-report no. 62 – Regional differences in traffic accidents" (PDF). Bureau de prévention des accidents. p. 71. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "Airport traffic statistics" (PDF). Airports Council International. 6 December 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "About Franklin - the International Imperative - Franklin College". Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- Kincaid, John; Alan Tarr, George (2005). Constitutional Origins, Structure, and Change in Federal Countries. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 349. ISBN 9780773528499.

On the south side of the Alps, the Canton of Ticino and parts of the Engadine Valley enjoy certain characteristics of Mediterranean culture.

- "Cenobio: rivista trimestrale di cultura della Svizzera italiana". Cenobio: 103. 2002.

I diversi ingredienti dell'appartenenza nazionale e del sentimento patrio dei ticinesi rivelano un'apparente ambivalenza, incomprensibile se non si considera la natura duplice e complessa dell'identità ticinese. Durante i tre secoli di dominazione elvetica nei baliaggi meridionali, anche se perdura l'identità dei ticinesi con la stirpe italica (grazie soprattutto ai tradizionali scambi commerciali e umani con la Lombardia), il loro carattere di "italianità" si amalgama progressivamente – risultato delle strette consuetudini statuali, politiche e amministrative – con quello insorgente di "svizzerità" (elvetismo).

[The different ingredients of national belonging and the homeland sentiment of the Ticinese reveal an apparent ambivalence, incomprehensible if one does not consider the dual and complex nature of the Ticinese identity. During the three centuries of Swiss domination in the southern bailiwicks, even if the identity of the Ticinese with the Italic lineage persists (thanks above all to the traditional commercial and human exchanges with Lombardy), their "Italian" character gradually amalgamates - the result of strict state, political and administrative customs - with the rising one of "Swissness".] - Atti di Convegno internazionale di studi: L'umanesimo latino in Svizzera. Fondazione Cassamarca. 2002. p. 64. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

importante ricordare che all'inizio del Novecento il Ticino aveva appena un secolo di esistenza autonoma, che l'identità ticinese si era formata a poco a poco nell'Ottocento grazie agli sforzi di personalità come Carlo Cattaneo e Stefano Franscini

[it is important to remember that at the beginning of the twentieth century Ticino had barely a century of autonomous existence, that the Ticinese identity was gradually formed in the nineteenth century thanks to the efforts of personalities such as Carlo Cattaneo and Stefano Franscini] - Lepori, Pierre (2008). Il teatro nella Svizzera italiana: la generazione dei "fondatori" (1932-1987). Casagrande. p. 24. ISBN 9788877135155.

Francesco Chiesa (che pure aveva attribuito al Ticino l'epiteto di "Repubblica dell'iperbole") su "La Voce" (18 dicembre 1912) afferma: "I Ticinesi hanno generalmente un concetto altissimo del loro paese, delle loro istituzioni, dei loro uomini. Un critico rigido potrebbe in alcuni casi trovare esagerate le lodi, e un tantino eroicomico il tono (...). Ma è bello e quasi commovente che in un paese di tenaci odi politici e di così voluttuosi pettegolezzi, tutti: rossi e neri, campagnuoli e cittadini, siano tanto concordi in questo sentimento di esaltata stima".

- "République" (in French). Historical Dictionary of Switzerland. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

Les nouveaux cantons de la Suisse latine choisirent le titre de république, qui soulignait leur indépendance, alors que "canton" met l'accent sur l'appartenance à la Confédération; Genève, Neuchâtel et le Tessin l'ont conservé jusqu'à nos jours.

[The new cantons of Latin Switzerland chose the title of republic, which underlined their independence, while "canton" emphasizes membership of the Confederation; Geneva, Neuchâtel and Ticino have kept it to this day.] - "Canton Ticino: a taste" (PDF). Swissnews.ch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- "The Architecture of Ticino "Tendenza" – a case of the past?" (PDF). BTU Cottbus. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- K. Michael Hays (2000). Architecture Theory Since 1968. MIT Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-262-58188-2.

- Max Oettli (2011). CultureShock! Switzerland. Marshall Cavendish. p. 189. ISBN 978-981-4435-93-2.

- Nicola Williams; Damien Simonis; Kerry Walker (2009). Switzerland. Lonely Planet. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-74220-381-2.

- Joanne Lane (1 July 2007). Adventure Guide to Sicily. Hunter Publishing, Inc. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-58843-627-6.

- "150 anni di Rabadan, vuoi rivederlo?". Radiotelevisione svizzera. 9 February 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- Gentile, Gianni (1991). La vita quotidiana in Svizzera dal 1300. Armando Dadò Editore. p. 275. ISBN 9788885115293.

Sono fioriti però anche differenti generi di musica popolare: nella Svizzera tedesca i Ländler e le sonorità del corno delle Alpi e degli Jodler. L'arte del coro è stata coltivata nella Svizzera romanda e nel Grigioni romancio grazie a una preesistente ricca tradizione. Nel Ticino e in Italia invece fu soprattutto l'opera di stile veristico a diventare patrimonio popolare. I garzoni panettieri e macellai, mentre pedalavano sulle loro biciclette per fare le consegne, zufolavano le arie più famose di Verdi, Puccini e Mascagni.

[However, different genres of popular music also flourished: in German-speaking Switzerland the Ländler and the sounds of the Alphorn and the Jodlers. Choir art was cultivated in French-speaking Switzerland and Romansh Grisons thanks to a pre-existing rich tradition. In Ticino and Italy, on the other hand, it was above all the veristic style work that became popular heritage. The bakers and butchers, while pedaling on their bicycles to make deliveries, whistled the most famous arias of Verdi, Puccini and Mascagni.] - Aonzo, Carlo (2015). Northern Italian & Ticino Region Folk Songs for Mandolin. Mel Bay Publications. p. 5. ISBN 9781610659406.

il mandolino è arrivato in Ticino, e qui ha messo delle importanti radici, essendo tra i principali rappresentanti del patrimonio culturale locale

[the mandolin arrived in Ticino, and here it has taken roots, being among the main representatives of the local cultural heritage] - Rice, Timothy (2017). "Switzerland: The Italian-speaking part". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: Europe. Routledge. ISBN 9781351544269.

- "Tessiner Polenta". TicinoTopTen. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- Oettli, Max (2011). CultureShock! Switzerland. Marshall Cavendish. p. 158. ISBN 9789814435932.

- "Salumi: Prodotti tipici". Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- "Olio d'oliva ticinese". Culinary Heritage of Switzerland. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

Nel 1494, 1600 e 1709, gli oliveti vennero quasi completamente distrutti dal gelo. Anni dopo, furono accantonati in favore dei gelsi, così da promuovere l'allevamento dei bachi da seta. Verso la fine degli anni '80 del secolo scorso, la coltivazione dell'olivo è stata ripresa

[In 1494, 1600 and 1709, frost destroyed almost all the olive trees. Later, they were replaced by mulberry trees to promote the breeding of silkworms. Olive cultivation in Ticino was revived at the end of the 1980s] - "Torta di Pane". Culinary Heritage of Switzerland. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- "Panettone". Culinary Heritage of Switzerland. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- "Panettone al cioccolato, un ticinese batte tutti" [Chocolate panettone, a Ticinese beats everyone]. Radiotelevisione svizzera. 21 December 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- "Gazosa – die Kultlimonade aus dem Tessin". Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- "La gazzosa ticinese sfonda il Gottardo" (PDF). Il Caffè. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- "What is a Boccalino?". Boccalino Grotto. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- "Presse: les titres participants" (PDF). REMP. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "REMP bulletin des tirages 2014" (PDF). REMP. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "Boccia – vom Zeitvertreib zum Leistungssport: Kommen die Kugelschieber zu olympischen Ehren?". NZZ.ch. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- Nicht, Christoph. "Pietro Magno und die italienischen Stukkateurtrupps" (PDF). Frankenland.franconica.uni-wuerzburg.de. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

Bibliography

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Coolidge, William Augustus Brevoort (1911). "Ticino". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 933–934.

- Marcello Sorce Keller,"Canton Ticino: una identità musicale?", Cenobio, LII(2003), April–June, pp. 171–184; also later published in Bulletin – Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Musikethnologie und Gesellschaft für die Volksmusik in der Schweiz, October 2005, pp. 30–37.

External links

Media related to Canton of Ticino at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Canton of Ticino at Wikimedia Commons- Cantone Ticino (in Italian) official site

- Ticino Tourism, official website of tourism office

- Official statistics

- "Ticino in a nutshell" (PDF). Repubblica e Cantone Ticino, Dipartimento delle istituzioni Residenza governativa. 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)