Parliament of the Cook Islands

The Parliament of the Cook Islands (Cook Islands Māori: Te Marae Akarau Vānanga o te Kuki Airani[2]) is the legislature of the Cook Islands. Originally established under New Zealand’s United Nations mandate it became the national legislature on independence in 1965.

Parliament of the Cook Islands Te Marae Akarau Vānanga o te Kuki Airani | |

|---|---|

Official Emblem of the Parliament of the Cook Islands[1] | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

Deputy Speaker | |

Leader of the Opposition | |

| Structure | |

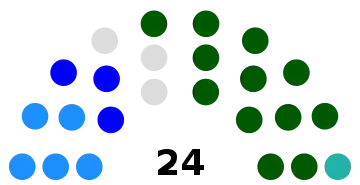

| Seats | 24 |

| |

Political groups | Government (14)

Opposition (10) |

| Elections | |

Last election | 1 August 2022 |

Next election | TBD |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Website | |

| Parliament of the Cook Islands | |

|

|---|

The Parliament consists of 24 members directly elected by universal suffrage from single-seat constituencies. Members are elected for a limited term, and hold office until Parliament is dissolved (a maximum of four years).[3] It meets in Avarua, the capital of the Cook Islands, on Rarotonga.

The Cook Islands follows the Westminster system of government, and is governed by a cabinet and Prime Minister commanding a majority in Parliament.

The Speaker of the House is currently Tai Tura. The Deputy Speaker is Tingika Elikana.[4]

History

The Cook Islands Parliament is descended from the Cook Islands Legislative Council established in October 1946.[5] Established to provide for political representation and better local government in the islands, the Legislative Council was a subordinate legislature. It was empowered to legislate for the "peace, order, and good government" of the islands, but could not pass laws repugnant to the laws of New Zealand, appropriate revenue, impose import or export duties, or impose criminal penalties in excess of one year's imprisonment or a £100 fine.[6] The council consisted of 20 members, ten "official" members appointed by the Governor-General of New Zealand and ten "unofficial" members drawn from the Island Councils, presided over by the Resident Commissioner. Later regulations provided for the unofficial members to be split between the various islands, 3 from Rarotonga, 6 from the outer islands and 1 representing the islands' European population.[7] The island representatives were elected annually, while the European representative was elected to a three-year term.[6]

The Legislative Council was reorganised in 1957 as the Legislative Assembly with 22 elected members and 4 appointed officials.[8] Fifteen of the members were elected directly by secret ballot, and seven were elected by the Island Councils.[9] In 1962, the Assembly was given full control of its own budget.[9] In that year it also debated the country's political future and chose self-government in free association with New Zealand.[10] On independence in 1965 it gained full legislative power.[11] It was renamed the Parliament of the Cook Islands in 1981.[12]

Both the size and term of Parliament have fluctuated since independence. In 1965, it consisted of 22 members elected for a period of 3 years.[13] The size was increased to 24 members in 1981, and again to 25 in 1991.[14] It was reduced again to 24 members in 2003 when the overseas constituency created under the 1980–81 Constitution Amendment was abolished.[15] The original three-year term was increased to four years in 1969,[16] and five years in 1981.[12] A referendum to reduce it to four years failed to gain the necessary two-thirds majority in 1999,[10] but passed in 2004.[17][18]

Membership and elections

The Cook Islands Parliament takes the British House of Commons as its model. It consists of 24 members, known as "Members of Parliament" (MPs). Members are elected by universal suffrage using the first-past-the-post system from single-seat constituencies. Ten MPs are elected from constituencies on the main island of Rarotonga, three each from the islands of Aitutaki and Mangaia, two from Atiu, and one each from the islands of Manihiki, Mauke, Mitiaro, Penrhyn, Pukapuka and Rakahanga.[19]

The executive branch of the Cook Islands government (the Cabinet) draws its membership exclusively from Parliament, based on which party or parties can claim a majority.[20] The Prime Minister leads the government; the King's Representative appoints the Prime Minister from the party or coalition that has or appears to have enough support to govern.[21] The Prime Minister and Cabinet hold office until the next election, or until they are defeated on a motion of confidence.[22] The Cook Islands has a two-party system, though independent members are not uncommon.

The Prime Minister is currently Mark Brown of the Cook Islands Party and the leader of the opposition is Tina Browne, who leads the Democratic Party.

Last election results

Summary of the 1 August 2022 Cook Islands election results:

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |

| Cook Islands Party | 3,890 | 44.07 | 12 | +2 | |

| Democratic Party | 2,377 | 26.93 | 5 | -6 | |

| Cook Islands United Party | 1,660 | 18.81 | 3 | New | |

| One Cook Islands Movement | 237 | 2.68 | 1 | NC | |

| Progressive Party of the Cook Islands | 18 | 0.20 | 0 | New | |

| Independents | 645 | 7.31 | 3 | +1 | |

| Total | 8,827 | 100.00 | 24 | 0 | |

| Source: MFEM | |||||

Passage of legislation

The Cook Islands Parliament follows the model common to other Westminster systems for passing Acts of Parliament. Laws are proposed to Parliament as bills. They become Acts after being approved three times by Parliament and receiving the assent of the King's Representative. Most bills are introduced by the government, but individual MPs can also promote their own bills, and one day a week is set aside for member's business.[23]

Debate is severely limited, with no debate on the First or Third readings, and possibly none on the Second. Voting is by voice vote or division, and there is no provision for proxy voting.[24]

First Reading

The first stage of the process is the First Reading. The bill is formally presented to Parliament, and the short title is read by the Clerk. There is no debate, and no vote.[25]

For the purposes of the First Reading a bill may consist only of its short title.[26]

Second Reading

The Second Reading may take place at any time up to a month after the first.[27] There is normally a debate on the general principles and merits of the bill,[28] with speeches of up to 20 minutes long.[29] If the bill is approved, then its long title is read, and it is either committed for the Committee of the whole House, or sent by motion to a Select Committee or to the House of Ariki.[30]

If a bill is intended to be sent to Select Committee or the House of Arikis, the Second Reading is pro forma, and there is no debate.[31]

Consideration by Select Committee or House of Ariki

Bills may be sent to a Select Committee or to the House of Ariki for consideration.[32] The committee or House of Ariki typically has three months to consider the bill, though this time may be extended.[33] Parliament may give instructions extending or restricting the terms of the committee's or House or Ariki's consideration.[34]

Following consideration, the House votes on whether to adopt the committee or House of Ariki's report.[35] If the motion passes, the bill goes straight to its Third Reading, without a Committee of the whole.[36] Alternatively, the bill may be recommitted for consideration by the Committee of the Whole.[37]

Committee of the whole House

When a bill reaches the Committee of the whole House stage, Parliament resolves itself "into committee", forming a committee of all MPs present to consider it. Each Member may speak up to three times on each clause or proposed amendment, for up to 10 minutes at a time,[29] but debate is restricted to the details of the bill rather than its principles.[38] The Committee may amend the bill as it sees fit, provided the amendments are relevant to the subject matter of the bill and the particular clause, and not inconsistent with any clause already agreed to.[39] Amendments may be introduced during the debate, or in writing and placed on the Order Paper.[40]

When all clauses have been debated and amendments agreed to or negatived, the bill is reported back, and there is a final vote on whether the report of the committee is adopted by the House.[41]

Third Reading

The Third Reading may be taken on the same day as a bill is reported back by the Committee of the whole, the House of Ariki or Select Committee.[42] Minor amendments may be proposed for correcting errors or oversights, but no material amendments may be proposed.[43] There is no debate.[44] If the bill is passed, it is referred to the King's Representative for their assent.

Select committees

Legislation is scrutinised by select committees, which must consist of between five and seven members.[45] Committees have the power to send for witnesses and records to assist in their deliberations.[46] As in other Westminster Systems, the proceedings of select committees are protected by Parliamentary privilege.[47]

The number and roles of subject committees is regulated by Standing Orders.[48] Currently the following subject committees exist:

| Select Committee | Areas of responsibility |

|---|---|

| Commerce | Business development, commerce, communications, consumer affairs, energy, information technology, insurance, and superannuation. |

| Education and Science | Education, industry training, research, science, and technology. |

| Finance and Expenditure | Audit of the Crown's and departmental financial statements, review of departmental performance, Government finance, revenue and taxation. |

| Foreign Affairs, Immigration, and Trade | Customs, defence, disarmament and arms control, foreign affairs, immigration and trade. |

| Land, Local Government, and Cultural Affairs | Land, Outer Islands, local government, culture, language, traditional affairs. |

| Law and Order | Courts, prisons, police. |

| Labour | Labour, employment relations, occupational health and safety. |

| Privileges | Powers privileges, and immunities of Parliament and its members. |

| Social Services, Health, and Environment | Housing, senior citizens, social welfare, work and income support, public health, environment, conservation. |

In addition there are three standing select committees tasked with the regulation of parliament. These are:

| Select Committee | Areas of responsibility |

|---|---|

| Government Caucus Committee | Business of Parliament each day and the order in which it is taken.[49] |

| Standing Orders Committee | Amendments to Standing Orders.[50] |

| Bills Committee | Private bills.[51] |

Terms of the Cook Islands Parliament

The Parliament is currently in its 15th term.

| Term | Elected in | Government |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Parliament | 1965 election | Cook Islands Party |

| 2nd Parliament | 1968 election | Cook Islands Party |

| 3rd Parliament | 1972 election | Cook Islands Party |

| 4th Parliament | 1974 election | Cook Islands Party |

| 5th Parliament | 1978 election | Democratic Party |

| 6th Parliament | March 1983 election | Cook Islands Party |

| 7th Parliament | November 1983 election | Democratic Party |

| 8th Parliament | 1989 election | Cook Islands Party |

| 9th Parliament | 1994 election | Cook Islands Party |

| 10th Parliament | 1999 election | Democratic Party |

| 11th Parliament | 2004 election | Democratic Party |

| 12th Parliament | 2006 election | Democratic Party |

| 13th Parliament | 2010 election | Cook Islands Party |

| 14th Parliament | 2014 election | Cook Islands Party |

| 15th Parliament | 2018 election | Cook Islands Party |

| 16th Parliament | 2022 election | Cook Islands Party |

See also

References

- "Parliament Emblem" (PDF). parliamentci.wpenginepowered.com. The Cook Islands Gazette. 21 September 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "Parliament of the Cook Islands". parliament.gov.ck/. Parliament of the Cook Islands. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- Cook Islands Constitution, s37 (5)

- Melina Etches (23 March 2021). "Mauke MP Tura appointed Speaker of Parliament". Cook Islands News. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- Cook Islands Amendment Act (NZ) 1946.

- Richard Gilson (1980). Ron Crocombe (ed.). The Cook Islands 1820-1950. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University of Wellington. p. 200. ISBN 0-7055-0735-1.

- Scott, Dick (1991). Years of the Pooh-Bah : a Cook Islands history. Auckland: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Cook Islands Amendment Act (NZ) 1957.

- Stone, David (1965). "The Rise of the Cook islands Party". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 74 (1): 81.

- "New Zealand - Cook Islands". Commonwealth Secretariat. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- "Voyage to Statehood". Cook Islands Government. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Constitution Amendment (No 9) Act 1980-81, s5

- Cook Islands Constitution Act (New Zealand) 1964, s27 and 37

- Constitution Amendment (No 14) Act 1991, s3

- Constitution Amendment (No 26) Act 2003, s3(a)

- Constitution Amendment Act 1968-69

- "Cook Islands parliament term to be put to voters". RNZ. 12 August 2004. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "Senior Cook Islands politician appears to lose seat in General Elections". Radio New Zealand International. 13 September 2004. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- Cook Islands Constitution, s27 (2).

- Cook Islands Constitution, s13 (3).

- Cook Islands Constitution, s13 (2).

- Cook Islands Constitution, s14 (3).

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 65.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Part XXVIII.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Orders 227, 228.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 227.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 229.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 230.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 391.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 234.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 235.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 259.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Orders 260, 261.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 312.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 266.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 267.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 268.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 238.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 241.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Orders 243, 244.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 253.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 269.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 270.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 272.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 317.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 335.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 346.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 316.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 359.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 360.

- Standing Orders of the Parliament of the Cook Islands, Standing Order 284-285; 361.