Argentina–Brazil football rivalry

The Brazil–Argentina football rivalry is a sports rivalry between the national football teams of the two countries and their respective sets of fans.[3] Games between the two teams are often marked by notable and controversial incidents. The rivalry has also been referred to as the Battle of the Americas or the Superclassic of the Americas (Spanish: Superclásico de las Américas; Portuguese: Superclássico das Américas). FIFA has described it as the "essence of football rivalry".[4] CNN ranked it second on their top 10 list of international football rivalries—only below the older England–Scotland football rivalry.[5]

Marcelo (Brazil) and Lionel Messi (Argentina) during a match of the 2008 Summer Olympics | |

| Other names | Clásico del Atlántico or Clássico do Atlântico |

|---|---|

| Location | CONMEBOL |

| Teams | |

| First meeting | Argentina 3-0 Brazil Friendly 20 September 1914[1] |

| Latest meeting | Argentina 0–0 Brazil 2022 World Cup qualification 16 November 2021 |

| Statistics | |

| Meetings total | 109 |

| Most player appearances | Javier Zanetti (16) |

| Top scorer | Pelé (8) |

| Largest victory | Brazil 1–6 Argentina Roca Cup 5 March 1940[2] |

Brazil-Argentina matches are often known for the high level of competitiveness and talent between the two teams.[6] Brazil and Argentina have the highest average football Elo Rating calculated over the entire team history.[7] Both are also routinely ranked among the top ten national teams in the world in both the FIFA World Rankings and the World Football Elo Ratings.[8] Both countries have produced players considered at the time the best in the world, such as Alfredo Di Stéfano, Diego Maradona, and Lionel Messi for Argentina and Pelé, Ronaldo, and Ronaldinho from Brazil.[9]

History

The origins of the football rivalry between Argentina and Brazil can be traced to a time before football became popular in both countries.[10] Their rivalry is found in almost all sports, but a men's football match between Argentina and Brazil is particularly important.

No matches were held between 1925 and 1937 after a violent Copa América final as both teams declined to compete in competitions in which the other was competing. After another violent encounter in 1946, the two teams did not play against each other for ten years. In another controversial game at the 1990 World Cup, Brazilian Branco accused an Argentina coach of lacing his water bottle with tranquilizers. Maradona would later describe it as "Holy Water".[11]

Since their first match in 1914, the men's national teams have played 107 matches including friendlies, FIFA World Cup matches, and other official competitions (excluding matches between youth sides). Although the number of matches figures is disputed as some matches in early years are not universally accepted due to debates over the establishment of the true Brazil team.[12]

Argentina dominated the early years with more than double the Brazilian victories, despite Brazil winning World Cups in 1958 and 1962. However, the 1970s proved to be dark times for Argentina, with seven defeats, four draws, and only one victory. Argentina did win the 1978 World Cup, drawing with Brazil along the way.

The highest scoring wins between these two nations were for Argentina 6–1 (at home in Buenos Aires, 1940) and 1–5 (away at Rio de Janeiro, 1939), for Brazil 6–2 (at home in Rio de Janeiro, 1945) and 1–4 (away at Buenos Aires, 1960).

The most important victory matches between these two nations were, for Argentina, the 2–0 match in the 1937 Copa América final,[13] the 0–0 draw in the 1978 World Cup that helped Argentina reach the final and their first World Cup title, the 1–0 victory over Brazil in the 1990 World Cup which eliminated Brazil from the World Cup in the round of 16, and the 1–0 victory over Brazil in the 2021 Copa América final, played in the Maracanã Stadium.

For Brazil, the most important victories were wins in two Copa América finals. The first, held in Peru in 2004, saw Brazil win 4–2 via a penalty shoot-out after the match had ended in 2–2 draw, and the second was a 3–0 win in the 2007 final played in Venezuela.[14] Another notable victory for Brazil was the 2005 FIFA Confederations Cup final, where they defeated Argentina 4–1 in the decisive match.

Statistics

Major official titles comparison

| Senior titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| FIFA World Cup | 3 | 5 |

| FIFA Confederations Cup | 1 | 4 |

| Copa América | 15 | 9 |

| Panamerican Championship | 1 | 2 |

| CONMEBOL–UEFA Cup of Champions | 2 | 0 |

| Total senior titles | 22 | 20

|

| Youth titles | ||

| Summer Olympics | 2 | 2 |

| Pan American Games | 7 | 4 |

| South American Games | 2 | 0 |

| CONMEBOL Pre-Olympic Tournament | 5 | 7 |

| FIFA U-20 World Cup | 6 | 5 |

| FIFA U-17 World Cup | 0 | 4 |

| South American U-20 Championship | 5 | 12 |

| South American U-17 Championship | 4 | 13 |

| South American U-15 Championship | 1 | 5 |

| Total youth titles | 32 | 52 |

| Grand total | 54 | 72 |

Head-to-head

- As of 15 December 2022

| Tournament | Matches played | Argentina win | Draw | Brazil win | Argentina goals | Brazil goals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIFA World Cup | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| FIFA Confederations Cup | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Copa América | 34 | 16 | 8 | 10 | 53 | 40 |

| FIFA World Cup qualification | 9 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 15 |

| Panamerican Championship | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Total official matches | 51 | 20 | 13 | 18 | 70 | 68 |

| Mundialito | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Roca Cup (1914–1974)[15] | 21 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 50 | 45 |

| Superclásico de las Américas | 8 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 8 |

| Taça do Atlântico (+1976 Roca Cup)[note 1] | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| Copa ZH 35th Anniversary [note 2] | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Copa Roberto Chery[18] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Copa Confraternidad[19] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Taça das Nações[20] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Australia Bicentenary Gold Cup[21] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Copa Centenario de la AFA [note 3] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Copa 50imo Aniversario de Clarín [note 4] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Friendly matches | 17 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 23 | 24 |

| Grand total | 109 | 40 | 26 | 43 | 162 | 166 |

Knockouts

- 1937 South American Championship final: Argentina 2–0 Brazil – Argentina champions

- 1990 FIFA World Cup round of 16: Argentina 1–0 Brazil – Argentina advanced

- 1993 Copa América quarter-final: Argentina 1–1 (6–5 p) Brazil – Argentina advanced

- 1995 Copa América quarter-final: Argentina 2–2 Brazil – Brazil advanced

- 1999 Copa América quarter-final: Argentina 1–2 Brazil – Brazil advanced

- 2004 Copa América final: Argentina 2–2 (2–4 p) Brazil – Brazil champions

- 2005 FIFA Confederations Cup final: Argentina 1–4 Brazil – Brazil champions

- 2007 Copa América final: Argentina 0–3 Brazil – Brazil champions

- 2019 Copa América semi-final: Argentina 0–2 Brazil – Brazil advanced

- 2021 Copa América final: Argentina 1–0 Brazil – Argentina champions

List of matches

Complete list of matches between both sides:

Note: Matches held before 1914[lower-alpha 1] are not recognized by FIFA so the International Federation considers that Brazilian squads formed until then were not official representatives of the country.

Before 1914, Argentina had toured Brazil twice, the first time in 1908,[24] returning in 1912.[25]

Recognised matches

| # | Date | City | Venue | Winner | Score | Competition | Goals (ARG) | Goals (BRA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 September 1914 | Buenos Aires | GEBA | Argentina | 3–0 | Friendly | Izaguirre (2), Molfino | |

| 2 | 27 September 1914 | Buenos Aires | GEBA | Brazil | 1–0 | Roca Cup | Salles | |

| 3 | 10 July 1916 | Buenos Aires | GEBA | (Draw) | 1–1 | 1916 Sudamericano | Laguna | Alencar |

| 4 | 3 October 1917 | Montevideo | Parque Pereira | Argentina | 4–2 | 1917 Sudamericano | Calomino, Ohaco (2), Blanco | Neco, S. Lagreca |

| 5 | 18 May 1919 | Rio de Janeiro | Laranjeiras | Brazil | 3–1 | 1919 Sudamericano | Izaguirre | Heitor, Amílcar, Millon |

| 6 | 1 June 1919 | Rio de Janeiro | Laranjeiras | (Draw) | 3–3 | Copa Roberto Chery | Clarke, Mattozzi, Laiolo | Arlindo (2), Haroldo |

| 7 | 25 September 1920 | Viña del Mar | Valparaíso SC | Argentina | 2–0 | 1920 Sudamericano | Echeverría, Libonatti | |

| 8 | 6 October 1920 | Buenos Aires | Sp. Barracas | Argentina | 3–1 | Friendly | Echeverría (2), Lucarelli | Castelhano |

| 9 | 2 October 1921 | Buenos Aires | Sp. Barracas | Argentina | 1–0 | 1921 Sudamericano | Libonatti | |

| 10 | 15 October 1922 | Rio de Janeiro | Laranjeiras | Brazil | 2–0 | 1922 Sudamericano | Neco, Amílcar (p) | |

| 11 | 22 October 1922 | São Paulo | Parque Antártica | Brazil | 2–1 | Roca Cup | Francia | Brasileiro, Gamba |

| 12 | 18 November 1923 | Montevideo | Parque Central | Argentina | 2–1 | 1923 Sudamericano | Onzari, Saluppo | Nilo |

| 13 | 2 December 1923 | Buenos Aires | Sp. Barracas | Brazil | 2–0 | Copa Confraternidad | Nilo, Zezé | |

| 14 | 9 December 1923 | Buenos Aires | Sp. Barracas | Argentina | 2–0 | Roca Cup | Dino (og), Onzari | |

| 15 | 13 December 1925 | Buenos Aires | Sp. Barracas | Argentina | 4–1 | 1925 Sudamericano | Seoane (3), Garasini | Nilo |

| 16 | 25 December 1925 | Buenos Aires | Boca Juniors | (Draw) | 2–2 | 1925 Sudamericano | Cerroti, Seoane | Friedenreich, Nilo |

| 17 | 30 January 1937 | Buenos Aires | Gasómetro | Argentina | 1–0 | 1937 Sudamericano | E. García | |

| 18 | 1 February 1937 | Buenos Aires | Gasómetro | Argentina | 2–0 | 1937 Sudamericano | De la Mata (2) | |

| 19 | 15 January 1939 | Rio de Janeiro | São Januário | Argentina | 5–1 | Roca Cup | E. García, Masantonio (2), Moreno (2) | Leônidas |

| 20 | 22 January 1939 | Rio de Janeiro | São Januário | Brazil | 3–2 | Roca Cup | Rodolfi, E. García | Leônidas, Adílson, Perácio (p.) |

| 21 | 18 February 1940 | São Paulo | Parque Antártica | (Draw) | 2–2 | Roca Cup | Cassan, Baldonedo | Leônidas (2) |

| 22 | 25 February 1940 | São Paulo | Parque Antártica | Argentina | 3–0 | Roca Cup | Baldonedo, Fidel, Sastre | |

| 23 | 5 March 1940 | Buenos Aires | Gasómetro | Argentina | 6–1 | Roca Cup | Masantonio (2), Peucelle (3), Baldonedo | Jair |

| 24 | 10 March 1940 | Buenos Aires | Gasómetro | Brazil | 3–2 | Roca Cup | Baldonedo (2) | Hércules (2), Leônidas |

| 25 | 17 March 1940 | Avellaneda | Independiente | Argentina | 5–1 | Roca Cup | Baldonedo, Masantonio (2), Peucelle, Cassan | Leônidas |

| 26 | 17 January 1942 | Montevideo | Centenario | Argentina | 2–1 | 1942 Sudamericano | E. García, Masantonio | Servílio Sr. |

| 27 | 16 February 1945 | Santiago | Nacional | Argentina | 3–1 | 1945 Sudamericano | N. Méndez | Ademir |

| 28 | 16 December 1945 | São Paulo | Pacaembu | Argentina | 4–3 | Roca Cup | Pedernera, Boyé, Sued, Labruna | Salomón (og), Zizinho, Ademir |

| 29 | 20 December 1945 | Rio de Janeiro | São Januário | Brazil | 6–2 | Roca Cup | Pedernera, Martino | Ademir (2), Leônidas (p.), Zizinho, Chico, Heleno de Freitas |

| 30 | 23 December 1945 | Rio de Janeiro | São Januário | Brazil | 3–1 | Roca Cup | Martino | Heleno de Freitas, E. Lima, Fonda (o.g.) |

| 31 | 10 February 1946 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | Argentina | 2–0 | 1946 Sudamericano | N. Méndez (2) | |

| 32 | 5 February 1956 | Montevideo | Centenario | Brazil | 1–0 | 1956 Sudamericano | Luizinho | |

| 33 | 18 March 1956 | Mexico D.F. | Municipal | (Draw) | 2–2 | 1956 Panamerican | Yudica, Sívori | Chinesinho, Ênio Andrade |

| 34 | 8 July 1956 | Avellaneda | Racing | (Draw) | 0–0 | Taça do Atlântico | ||

| 35 | 3 April 1957 | Lima | Nacional | Argentina | 3–0 | 1957 Sudamericano | Angelillo, Maschio, Cruz | |

| 36 | 7 July 1957 | Rio de Janeiro | Maracanã | Argentina | 2–1 | Roca Cup | Labruna, Juárez | Pelé |

| 37 | 10 July 1957 | São Paulo | Pacaembu | Brazil | 2–0 | Roca Cup | Pelé, Mazzola | |

| 38 | 4 April 1959 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | (Draw) | 1–1 | 1959 Sudamericano (A) | Pizzuti | Pelé |

| 39 | 22 December 1959 | Guayaquil | Modelo | Argentina | 4–1 | 1959 Sudamericano (E) | O.H. García, Sanfilippo (3) | Geraldo |

| 40 | 13 March 1960 | San José | Nacional | Argentina | 2–1 | 1960 Panamerican | Belén, Nardiello | Teixeira |

| 41 | 20 March 1960 | San José | Nacional | Brazil | 1–0 | Kuelle | ||

| 42 | 26 May 1960 | Buenos Aires | Monumnetal | Argentina | 4–2 | Roca Cup | Nardiello (2), D'Ascenzo, Belén | Djalma Santos, Delém |

| 43 | 29 May 1960 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | Brazil | 4–1 | Roca Cup | R. Sosa | Delém, Julinho, Servílio Jr. |

| 44 | 12 July 1960 | Rio de Janeiro | Maracanã | Brazil | 5–1 | Taça do Atlântico | R. Sosa | Chinesinho, Pelé, Pepe (2), Delém |

| 45 | 24 March 1963 | La Paz | Hernando Siles | Argentina | 3–0 | 1963 Sudamericano | M. Rodríguez, Savoy, Juárez | |

| 46 | 13 April 1963 | São Paulo | Morumbi | Argentina | 3–2 | Roca Cup | Lallana (2), Juárez | Pepe (2) |

| 47 | 16 April 1963 | Rio de Janeiro | Maracanã | Brazil | 5–2 | Roca Cup | Fernández, Savoy | Pelé (3), Amarildo (2) |

| 48 | 3 June 1964 | São Paulo | Pacaembu | Argentina | 3–0 | Taça das Nações | E. Onega, Telch (2) | |

| 49 | 9 June 1965 | Rio de Janeiro | Maracanã | (Draw) | 0–0 | Friendly | ||

| 50 | 7 August 1968 | Rio de Janeiro | Maracanã | Brazil | 4–1 | Friendly | Basile | Waltencir, R. Miranda, Jairzinho, Caju |

| 51 | 11 August 1968 | Belo Horizonte | Mineirão | Brazil | 3–2 | Friendly | Rendo, Silva | Evaldo, Rodrigues, Dirceu |

| 52 | 4 March 1970 | Porto Alegre | Beira-Rio | Argentina | 2–0 | Friendly | Mas, Conigliaro | |

| 53 | 8 March 1970 | Rio de Janeiro | Maracanã | Brazil | 2–1 | Friendly | Brindisi | Pelé, Jairzinho |

| 54 | 28 July 1971 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | (Draw) | 1–1 | Roca Cup | Madurga | Caju |

| 55 | 31 July 1971 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | (Draw) | 2–2 | Roca Cup | Fischer (2) | Tostão, Caju |

| 56 | 30 June 1974 | Hannover | Niedersachsenstadion | Brazil | 2–1 | 1974 World Cup | Brindisi | Rivellino, Jairzinho |

| 57 | 6 August 1975 | Belo Horizonte | Mineirão | Brazil | 1–2 | 1975 Copa América | Asad | Nelinho (2) |

| 58 | 16 August 1975 | Rosario | Gigante Arroyito | Brazil | 1–0 | 1975 Copa América | Danival | |

| 59 | 27 February 1976 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | Brazil | 2–1 | Taça do Atlântico + Roca Cup | Kempes | Lula, Zico |

| 60 | 19 May 1976 | Río de Janeiro | Maracanã | Brazil | 2–0 | Taça do Atlântico + Roca Cup | Lula, Neca | |

| 61 | 18 June 1978 | Rosario | Gigante Arroyito | (Draw) | 0–0 | 1978 World Cup | ||

| 62 | 2 August 1979 | Río de Janeiro | Maracanã | Brazil | 2–1 | 1979 Copa América | Coscia | Zico, Tita |

| 63 | 23 August 1979 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | (Draw) | 2–2 | 1979 Copa América | Passarella, R. Díaz | Sócrates (2) |

| 64 | 4 January 1981 | Montevideo | Centenario | (Draw) | 1–1 | Mundialito | Maradona | Edevaldo |

| 65 | 2 June 1982 | Barcelona | Sarrià | Brazil | 3–1 | 1982 World Cup | R. Díaz | Zico, Serginho, Júnior |

| 66 | 24 August 1983 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | Argentina | 1–0 | 1983 Copa América | Gareca | |

| 67 | 14 September 1983 | Rio de Janeiro | Maracanã | (Draw) | 0–0 | 1983 Copa América | ||

| 68 | 17 June 1984 | São Paulo | Morumbi | (Draw) | 0–0 | Friendly | ||

| 69 | 5 May 1985 | Salvador | Fonte Nova | Brazil | 2–1 | Friendly | Burruchaga | Careca, Alemão |

| 70 | 10 July 1988 | Melbourne | Olympic Park | (Draw) | 0–0 | Australia Bicentenary Gold Cup | ||

| 71 | 12 July 1989 | Rio de Janeiro | Maracanã | Brazil | 2–0 | 1989 Copa América | Bebeto, Romário | |

| 72 | 24 June 1990 | Turin | delle Alpi | Argentina | 1–0 | 1990 World Cup | Caniggia | |

| 73 | 27 March 1991 | Buenos Aires | José Amalfitani | (Draw) | 3–3 | Friendly | Ferreyra, Franco, Bisconti | Renato Gaúcho, Luís Henrique, Careca Bianchezi |

| 74 | 27 June 1991 | Curitiba | Pinheirão | (Draw) | 1–1 | Friendly | Caniggia | Neto |

| 75 | 17 July 1991 | Santiago | Estadio Nacional | Argentina | 3–2 | 1991 Copa América | Franco (2), Batistuta | Branco, Joao Paulo |

| 76 | 18 February 1993 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | (Draw) | 1–1 | Copa Centenario de la AFA | Mancuso | Luís Henrique |

| 77 | 27 June 1993 | Guayaquil | Monumental | (Draw) | 1–1 | 1993 Copa América | L. Rodríguez | Müller |

| 78 | 23 March 1994 | Recife | Arruda | Brazil | 2–0 | Friendly | Bebeto (2) | |

| 79 | 17 July 1995 | Rivera | Atilio Paiva | (Draw) | 2–2 | 1995 Copa América | Balbo, Batistuta | Edmundo, Túlio |

| 80 | 8 November 1995 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | Brazil | 1–0 | Copa 50imo Aniversario de Clarín | Donizete | |

| 81 | 29 Abr 1998 | Rio de Janeiro | Maracanã | Argentina | 1–0 | Friendly | C. López | |

| 82 | 11 June 1999 | Ciudad del Este | Antonio Aranda | Brazil | 2–1 | 1999 Copa América | Sorín | Rivaldo, Ronaldo |

| 83 | 4 September 1999 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | Argentina | 2–0 | Copa ZH 35th Anniversary | Verón, Crespo | |

| 84 | 7 September 1999 | Porto Alegre | Beira-Rio | Brazil | 4–2 | Copa ZH 35th Anniversary | Ayala, Ortega | Rivaldo (3), Ronaldo |

| 85 | 26 July 2000 | São Paulo | Morumbi | Brazil | 3–1 | 2002 World Cup qualification | Almeyda | Alex, Vampeta (2) |

| 86 | 5 September 2001 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | Argentina | 2–1 | 2002 World Cup qualification | Gallardo, Cris (o.g.) | Ayala (o.g.) |

| 87 | 2 June 2004 | Belo Horizonte | Mineirão | Brazil | 3–1 | 2006 World Cup qualification | Sorín | Ronaldo (3) |

| 88 | 25 July 2004 | Lima | Estadio Nacional | (Draw) | 2–2 | 2004 Copa América | K. González, Delgado | Luisão, Adriano |

| 89 | 8 June 2005 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | Argentina | 3–1 | 2006 World Cup qualification | Crespo (2), Riquelme | R. Carlos |

| 90 | 29 June 2005 | Frankfurt | Waldstadion | Brazil | 4–1 | 2005 FIFA Confederations Cup | Aimar | Adriano (2), Kaká, Ronaldinho |

| 91 | 3 September 2006 | London | Emirates Stadium | Brazil | 3–0 | Friendly | Elano (2), Kaká | |

| 92 | 15 July 2007 | Maracaibo | José P. Romero | Brazil | 3–0 | 2007 Copa América | J. Baptista, Ayala (o.g.), Dani Alves | |

| 93 | 18 June 2008 | Belo Horizonte | Mineirão | (Draw) | 0–0 | 2010 World Cup qualification | ||

| 94 | 5 September 2009 | Rosario | Gigante Arroyito | Brazil | 3–1 | 2010 World Cup qualification | Dátolo | Luisão, L. Fabiano (2) |

| 95 | 17 November 2010 | Doha | Khalifa International | Argentina | 1–0 | Friendly | Messi | |

| 96 | 14 September 2011 | Córdoba | Mario A. Kempes | (Draw) | 0–0 | 2011 Superclásico | ||

| 97 | 28 September 2011 | Belém | Mangueirão | Brazil | 2–0 | 2011 Superclásico | L. Moura, Neymar | |

| 98 | 9 June 2012 | East Rutherford | MetLife Stadium | Argentina | 4–3 | Friendly | Messi (3), F. Fernández | Rômulo, Oscar, Hulk |

| 99 | 19 September 2012 | Goiânia | Serra Dourada | Brazil | 2–1 | 2012 Superclásico | J.M. Martínez | Paulinho, Neymar |

| 100 | 21 November 2012 | Buenos Aires | La Bombonera | Argentina | 2–1 | 2012 Superclásico | Scocco (2) | Fred |

| 101 | 11 October 2014 | Beijing | National Stadium | Brazil | 2–0 | 2014 Superclásico | D. Tardelli (2) | |

| 102 | 13 November 2015 | Buenos Aires | Monumental | (Draw) | 1–1 | 2018 World Cup qualification | Lavezzi | L. Lima |

| 103 | 10 November 2016 | Belo Horizonte | Mineirão | Brazil | 3–0 | 2018 World Cup qualification | Coutinho, Neymar, Paulinho | |

| 104 | 9 June 2017 | Melbourne | Cricket Ground | Argentina | 1–0 | 2017 Superclásico | Mercado | |

| 105 | 16 October 2018 | Jeddah | King Abdullah | Brazil | 1–0 | 2018 Superclásico | Miranda | |

| 106 | 2 July 2019 | Belo Horizonte | Mineirão | Brazil | 2–0 | 2019 Copa América | G. Jesus, R. Firmino | |

| 107 | 15 November 2019 | Riyadh | King Saud | Argentina | 1–0 | 2019 Superclásico | Messi | |

| 108 | 10 July 2021 | Rio de Janeiro | Maracanã | Argentina | 1–0 | 2021 Copa América | Di María | |

| 109 | 16 November 2021 | San Juan | Bicentenario | (Draw) | 0–0 | 2022 World Cup qualification |

Unrecognised matches

List of matches played from 1908 to 1914 – before the CBF was established – between the Argentina national team and diverse representatives (named themselves "Brazil"), such as Liga Paulista and Liga Carioca combined, or clubs (Paulistano, SC Americano), among others. It is believed that in the first match held on 2 July 1908, Argentina wore the light blue and white shirt for the first time,[26] although other sources state that the shirt debuted in a Copa Newton match v Uruguay in September that year.[27] In 1913, a Liga Paulista team arrived in Argentina to play two friendly matches there.[26]

| # | Date | City | Venue | Winner | Score | Goals (ARG) | Goals (BRA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 July 1908 | São Paulo | Velódromo | (Draw) | 2–2 | J. Brown, E. Brown | Miller |

| 2 | 5 July 1908 | São Paulo | Velódromo | Argentina | 6–0 | Susán, E. Brown (3), A. Brown (2) | |

| 3 | 7 July 1908 | São Paulo | Velódromo | Argentina | 4–0 | Dickinson, Susán, A. Brown, E.A. Brown | |

| 4 | 9 July 1908 | Rio de Janeiro | Laranjeiras | Argentina | 3–2 | V. Etchegaray (o.g.), Dickinson, Burgos | Sampaio, E. Etchegaray (p.) |

| 5 | 11 July 1908 | Rio de Janeiro | Laranjeiras | Argentina | 7–1 | Robinson (o.g.), E.A. Brown (2), Burgos, E. Brown (2), Susán | Monk |

| 6 | 12 July 1908 | Rio de Janeiro | Laranjeiras | Argentina | 3–0 | E.A. Brown (3) | |

| 7 | 14 July 1908 | Santos | Liga Santista | Argentina | 6–1 | E.A. Brown (2), Susán (2), E. Brown (2) | Colston |

| 8 | 4 September 1912 | São Paulo | Velódromo | Brazil | 4–3 | Hayes (3) | Mariano, Décio (3) |

| 9 | 5 September 1912 | São Paulo | Velódromo | Argentina | 3–0 | J.D. Brown (p), E.A. Brown, Viale | |

| 10 | 7 September 1912 | São Paulo | Velódromo | Argentina | 6–3 | Susán, E.A. Brown (2), Viale, Hayes (2) | J.D. Brown (o.g.), Boyes, Manne |

| 11 | 8 September 1912 | São Paulo | Velódromo | Argentina | 6–3 | Susán (2), E.A. Brown (3), Hayes | Friedenreich, Malta, Salles |

| 12 | 12 September 1912 | Rio de Janeiro | Laranjeiras | Argentina | 4–0 | E.A.Brown, Ohaco, Hayes (2) | |

| 13 | 14 September 1912 | Rio de Janeiro | Laranjeiras | Argentina | 9–1 | (n/d) | Robinson |

| 14 | 15 September 1912 | Rio de Janeiro | Laranjeiras | Argentina | 5–0 | Hayes (4), Susán | |

| 15 | 10 August 1913 | Avellaneda | Racing | Brazil | 2–0 | Campos, Décio | |

| 16 | 17 August 1913 | Buenos Aires | GEBA | Argentina | 2–0 | Viale, Susán | |

| 17[note 5] | 5 December 1956 | Rio de Janeiro | Maracanã | Argentina | Sanfilippo, Garabal | Índio |

- 1976 Taça do Atlântico matches also counted for the 1976 Roca Cup[16][15]

- Organised by the Porto Alegre newspaper Zero Hora to celebrate its 35th. anniversary.[17]

- Organised by the Argentine Football Association to celebrate its 100th. anniversary. Not to be confused with the homonymous Argentine national cup.[22]

- Organised by Argentine newspaper Clarín to celebrate its 50th. anniversary.[23]

- This match was not of Brazil national team, but Rio de Janeiro state football team[28][29]

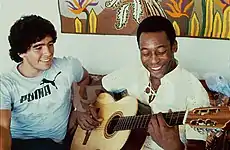

Pelé–Maradona rivalry

Among the elite group of players, football fans consider as contenders for the title, of the best player of all time, Brazil's Pelé and Argentina's Diego Maradona are amongst the most famous.[30][31] Some of their countrymen also feature regularly in such debates. The next most notable pair are perhaps Garrincha (Brazil)[32] Lionel Messi (Argentina) and Alfredo Di Stéfano (Argentina).[33] The most dominant figures from the two countries in the modern game are Neymar (Brazilian) and Messi, who both played for Paris Saint-Germain. Both Pelé and Maradona have declared Neymar and Messi their respective "successors".[34][35]

.jpg.webp)

However, the overriding discussion about which of Pelé and Maradona is the greater has proved to be never-ending. Many consider the comparison between them useless, as they played during incomparable eras and in different leagues.[36] The debate between the pair has been described as "the rivalry of their countries in microcosm".[37]

Pelé was given the title "Athlete of the Century" by the International Olympic Committee.[38] In 1999, Time magazine named Pelé one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century.[39] Also, he was elected Football Player of the Century, by France Football's Golden Ball Winners in 1999, Football Player of the Century, and South America Football Player of the Century, both by the International Federation of Football History & Statistics (IFFHS), 1999. For his part, Maradona has been named Best Player of the 20th Century by the Globe Soccer Awards,[40] the best soccer player in World Cup history both by The Times[41] and FourFourTwo regarded him as the "Best Football Player of All Time".[42] He was also elected as the "Greatest Athlete in History" by Corriere Dello Sport – Stadio.[43]

The controversy reached a climax during the FIFA Player of the Century in 2000, in which Maradona was voted Player of the Century in an official internet poll, garnering 53.6% of the votes against 18.53% for Pelé. Shortly before the ceremony, FIFA decided to add a second award and appointed a "Football Family" committee composed of football journalists that gave Pelé the title of The Best Player of the Century to make it a draw. This move was criticized in Argentina, that suspected Pelé was rewarded for his constant support of FIFA, in contrast to Maradona's frequent criticism.[30][44] Others believe that FIFA was considering issues other than football, notably Maradona's drug problem. Maradona left the ceremony right after receiving his award and before Pelé was given his.[45]

In another internet poll that took place in 2002, Maradona received another award from FIFA, as one of his goals was selected as the World Cup Goal of the Century. One of Pelé's goals received third place, while Maradona had a second goal selected as fourth.[45]

Despite their frequent confrontations,[46] usually through quotations by the media, Pelé was the guest star of Maradona's TV show La Noche del 10 ("The Night of the #10"), where they had a friendly chat and played a bout of headers.[47] The two players also showed great respect for each other despite differences, such as when Pelé stated in 2018 that Maradona was better than Messi, or in 2019 when Maradona prayed for Pelé to recover after the Brazilian legend was admitted to hospital for health reasons.[48][49] When Maradona died on 25 November 2020, Pelé was among the major football figures to mourn Maradona's death.[50]

Incidents and historical matches

1925 Copa América

For the 1925 Copa América, Argentina and Brazil played the final match at Sportivo Barracas Stadium, on Christmas Day, drawing a crowd of more than 30,000 people. After 27 minutes Lagarto intercepted a back pass by Ludovico Bidoglio and passed the ball to Arthur Friedenreich, who beat Américo Tesoriere with a strong shot, making it 1-0 to Brazil. Three minutes later, Nilo scored the second for the canarinha. The crowd was astonished, because if the Brazilian lead was maintained, a new match would have to be played to determine the champion.

Before completing the first half, a dangerous counterattack by the visitors was stopped by Ramón Muttis with a strong foul on Friedenreich, who in turn, reacted with a kick. The Argentine responded with a punch in the Brazilian's face, and the incident sparked a clash involving several players and some spectators invaded the pitch. The game was suspended and only resumed - without a sending-off - after a hug between Friedenreich and Muttis that sealed a truce. However, the match had changed course, at the end of the first half Antonio Cerrotti reduced the deficit and opened the road to recovery. The equaliser came ten minutes into the second half through Manuel Seoane. The match ended 2–2, and Argentina won its second Copa America. The incidents did not go unnoticed in Brazil and some local newspapers referred to the game as "The Barracas' War".[51]

Because of this match, Argentina and Brazil did not play officially again for 11 years.

1937 Copa América final

In the 1937 South American Championship (currently Copa América), the rivalry between both teams was already something of national pride. There were verbal confrontations between both parties, and Argentine fans often taunted the Brazilians by calling them macaquitos and making monkey sounds.[52] The final match, held in Buenos Aires, was played between the two sides and was goalless after 90 minutes. In extra time, Argentina scored two goals. Questioning one of the goals and fearful for their own safety, the Brazilian players decided to leave the stadium before the match was officially finished. The Brazilian press has since called this match "jogo da vergonha" ("the shame game").[53] Argentina won, 2–0, and was South American champion again.

1939 Copa Roca

The 1939 edition of the Roca Cup was the longest in history, having been defined after four matches. The first two games were held in Estádio São Januário in Rio de Janeiro. The first one, held in January, ended 5–1 to Argentina.[54]

A second match was held only one week later, with the Brazilian team seeking revenge for the previous defeat. The match was vibrating; first Brazil went ahead 1–0, then Argentina recovered to lead 1–2, and Brazil then drew level at 2–2. Shortly before the end of the match, the referee, the same as in the previous match, gave a penalty to Brazil. Furious, Argentina player Arcadio López verbally attacked the referee and had to be escorted out of the pitch by police. The Argentine team, enraged by the actions of the referee and the police, left the pitch. The penalty that gave Brazil the 3–2 victory was scored without a goalkeeper, because the entire Argentine team had already walked off the pitch.[53]

As both teams had won one match each, a third game was scheduled to be played at Parque Antarctica in São Paulo. The match ended 2–2 after extra time therefore a fourth and final match was held in the same venue and was won by Argentina 3–0, which finally won the trophy.

1945–1946 incidents

In the 1945 Copa Roca match that Brazil won 6–2, young Brazilian Ademir de Menezes fractured Argentine José Battagliero's leg.[55] Though it seemed to be only an unfortunate accident, the game was played roughly and sometimes violent.

A few months later, the 1946 South American Championship final again involved Argentina and Brazil. There was widespread media coverage, and the conviction that it would be a rough match. Twenty-eight minutes after the beginning, when both teams went for a free ball, Brazilian Jair Rosa Pinto fractured Argentine captain José Salomón's tibia and fibula. General disorder ensued, with Argentine and Brazilian players fighting on the pitch with the police. The public invaded the pitch and both teams had to go to the dressing rooms. After order was restored the game continued, and Argentina won the match 2–0. Salomón never recovered completely nor played professional football after the incident.[56]

1974 World Cup

It would be the first-ever meeting between Brazil and Argentina in the FIFA World Cup. Defending champions Brazil faced Argentina in West Germany's Niedersachsenstadion in Hanover in the second round as both were placed in Group A. Brazil won it by 2–1 via goals from Rivellino and Jairzinho whereas Brindisi scored the only goal for Argentina.[57]

1978 World Cup

The Group B of the second round was essentially a battle between Argentina and Brazil, and it was resolved in controversial circumstances. In the first round of group games, Brazil beat Peru 3–0 while Argentina saw off Poland 2–0. Brazil and Argentina then played out a tense and violent goalless draw – also known as "A Batalha de Rosário" ("The Battle of Rosario"), so both teams went into the last round of matches with three points. Argentina had an advantage that their match against Peru kicked off several hours after Brazil's match with Poland.

Brazil won their match 3–1, so Argentina could know that they had to beat Peru by four clear goals to go through to the final. Argentina managed it with what some saw as a suspicious degree of ease. Trailing 2–0 at half-time, Peru simply collapsed in the second half, and Argentina eventually won 6–0. Rumours suggested that Peru might have been somehow illicitly induced not to try too hard (especially because the Peruvian goalkeeper, Ramón Quiroga, was born in Argentina); but nothing could be proved, and Argentina met the Netherlands in the final.

Brazil, denied a final place by Argentina's 6–0 win over Peru, took third place from an enterprising Italy side and were dubbed "moral champions" by coach Cláudio Coutinho, because they did not win the tournament but did not lose a single match either.

1982 World Cup

Brazil and Argentina were grouped together (along with Italy) in the second group stage in Group C, which was dubbed as the "group of death". In the opener, Italy prevailed 2–1 over Argentina. Argentina now needed a win over Brazil on the second day, but they were no match, as the Brazilians' attacking game, characterised by nimble, one-touch passing on-the-run, eclipsed the reigning world champions. The final score of 3–1 – Argentina only scoring in the last minute – could have been much higher had Brazil centre-forward Serginho not wasted a series of near-certain scoring opportunities. Frustrated because of the poor refereeing and the imminent loss, Diego Maradona kicked Brazilian player Batista and received a straight red card. Brazil lost their next game to Italy and thus exited the World Cup along with Argentina.

1990 World Cup (The "holy water" scandal)

The teams met in the World Cup Round of 16 at the 1990 World Cup. Argentina defeated Brazil 1–0 with a goal from Claudio Caniggia after a pass from Diego Maradona. The end of the match was controversial, however, with Brazilian player Branco accusing the Argentina training staff of giving him a bottle of water laced with tranquillizers while they were tending to an injured player. Years later, Maradona admitted the truth on an Argentine television show, saying that Branco had been given "holy water". The Argentine Football Association and the team coach of the time, Carlos Bilardo, denied that the "holy water" incident ever took place,[11][58] though prior to the previous denial Bilardo said of Branco's allegation: "I'm not saying it didn't happen."[59]

1991 Copa América match

Argentina defeated Brazil 3–2 in Santiago in the first match of the final pool. Five players were sent off: Claudio Caniggia and Mazinho after tangling in the 31st minute; Carlos Enrique and Márcio Santos for another fight in the 61st minute, with one player leaving on a stretcher; and Careca Bianchezi in the 80th minute, two minutes after coming on as a substitute.[60]

1993 Copa América match

Argentina and Brazil finished 1–1 in the quarterfinal match, played in Guayaquil. Brazil took the lead, but Leonardo Rodríguez drew with the head after a corner kick in the second half. In penalties, Los Gauchos defeated Brazil 5–4 and advanced to the semi-finals. Argentina won the Copa América title after defeating Mexico in the final.

1995 Copa América match

Held in Uruguay, the two nations met at the quarter-finals stage on 17 July 1995. The Brazilian Túlio became famous for scoring a late equalizer five minutes from time after controlling the ball with his left arm. Despite the obvious foul, the referee, Alberto Tejada Noriega of Peru, claimed he did not see the incident and the goal therefore stood. The game finished with a 2–2 draw and Brazil went on to win on penalties. The Argentine media labeled the incident as the "hand of the devil",[61] a reference to the controversial goal scored by Diego Maradona in the 1986 World Cup against England.

2004 Copa América Final

Argentina was winning 2–1, but in a spectacular turn of events, Adriano scored a goal in the last minute of the match, taking the match to penalties, where Brazil won with Júlio César stopping a shot from Andrés D'Alessandro. Brazil were playing with its second-string team.

2005 Confederations Cup Final

In 2005, Brazil and Argentina participated in the 2005 FIFA Confederations Cup. Brazil entered the competition as the reigning World Cup champion at the time. Since Brazil had also won the Copa América the previous year, however, Copa runners-up Argentina was allowed to participate in the tournament to take up the vacated berth. In the semi-finals, Brazil eliminated host nation Germany, while Argentina eliminated Mexico. This competition was the first time the two rivals would meet in a final game of a tournament sponsored by FIFA. In a surprising turn of events, the Brazilian team won the game easily, thrashing the Argentines 4–1. Adriano scored twice for Brazil, along with Kaká and Ronaldinho, while Pablo Aimar scored Argentina's only goal.

2007 Copa América Final

Brazil defeated Argentina 3–0 in Maracaibo, Venezuela, in the final. The goals scored were by Júlio Baptista, an own goal by Roberto Ayala, and Dani Alves.

2008 Summer Olympics – Beijing

Defending champions Argentina and Brazil met on 19 August in the semifinal game of the Summer Olympics. The game was billed as a tête-à-tête between Lionel Messi and Ronaldinho, two Barcelona teammates. It was a hard-fought clash between two historic rivals, marred by numerous fouls and two red cards for Brazil. Argentina convincingly won with a score of 3–0, and went on to beat Nigeria 1–0 in the final, being the first to obtain two consecutive gold medals in football in 40 years, and the third overall after the Olympic teams of the United Kingdom and Uruguay. Brazil eventually won the gold medal at the Olympics themselves playing at home in 2016.

2019 Copa América

Brazil and Argentina met at the semifinal of the 2019 Copa América, which was hosted in Brazil. Brazil defeated Argentina 2–0 with goals by Gabriel Jesus and Firmino. Argentina eventually placed third and Brazil went on to win their 9th Copa América title.[62]

2021 Copa América Final

The 2021 Copa América was originally scheduled to be jointly held in Colombia and Argentina in 2020, but it was postponed to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Colombia and Argentina were removed as hosts due to social unrest in Colombia and the COVID-19 pandemic in Argentina. Brazil was chosen to host the tournament. In the final, Argentina defeated Brazil 1–0 with the only goal by Ángel Di María at the Maracanã Stadium to win their 15th Copa América title, their first in 28 years.[63]

Club-level official titles comparison

Note: Only official competitions (organised by CONMEBOL and/or other continental confederations) are included

- Note

- Defunct competition.[64]

Copa Libertadores de América

In the history of this tournament, played since 1960, only twice has a Brazilian team captured a title on Argentine soil. In 1963, Brazilian side Santos defeated the most popular Argentine club, Boca Juniors, and in 2017, when Grêmio defeated Club Atlético Lanús . However, the same Argentine club team, Boca Juniors, has celebrated three of its six titles on Brazilian soil, defeating Palmeiras in 2000, Santos in 2003 and Grêmio in 2007. The two greatest Argentine and Brazilian players that have ever played this sport had at one point played in these same two clubs: Pelé for Santos while Diego Maradona had done the same for Boca Juniors. It has been reported that in all three of Boca Juniors' victories on Brazilian soil, Boca's players were not allowed to properly sleep in their hotel rooms the night before their final matches because of the chaos and noise created by Brazilian fans outside the hotel rooms, who attempted to disrupt the Argentine players from performing to their best of their abilities the following day.

In the international arena, the most successful Argentine clubs are Boca Juniors (six Libertadores and three Intercontinental Cups), Independiente (seven Libertadores and two Intercontinental Cups), Estudiantes de La Plata (four Libertadores and one Intercontinental Cup), River Plate (four Libertadores and one Intercontinental Cup), Vélez Sársfield (one Libertadores and one Intercontinental), San Lorenzo (one Libertadores, one Copa Mercosur and one Copa Sudamericana), Argentinos Juniors (one Libertadores) and Racing Club (one Libertadores and one Intercontinental Cup).

The most successful Brazilian clubs are São Paulo (three Libertadores, one FIFA Club World Cup and two Intercontinental Cups), Santos (three Libertadores and two Intercontinental Cups), Grêmio (three Libertadores and one Intercontinental Cup), Palmeiras (three Libertadores, one Copa Mercosur and one Recopa Sudamericana), Internacional (two Libertadores and one FIFA Club World Cup), Cruzeiro (two Libertadores), Corinthians (one Libertadores and two FIFA Club World Cups), Flamengo, (two Libertadores, one Copa Mercosur, one Copa de Oro, one Recopa and one Intercontinental Cup), Vasco da Gama (one Libertadores, one South American Championship of Champions and one Copa Mercosur) AND Atlético Mineiro (one Libertadores and two Copa Conmebol).

Women's football

.jpg.webp)

The Brazil women's national team is a successful women's football team. It was runner-up in the FIFA Women's World Cup of 2007, and won a silver medal at the Olympic games in 2004 and 2008. In comparison, Argentina does not have a professional (or even semi-professional) women's football league; the members of the Argentina women's national football team are all amateur players despite their clubs often being affiliated with prominent men's professional clubs. Although the two teams usually have to battle for the top qualification spots for CONMEBOL when the World Cup qualification comes around, this rivalry does not provide the passion that men's matches encounter yet.

Brazil won every game of the Sudamericano Femenino against Argentina until the 2006 edition, when Argentina finally beat them 2–0 in the final group stage, awarding Argentina the championship. Argentina did not participate in the 1991 South American competition and was second to Brazil in the following three tournaments. Beginning with the 2003 edition, both champion and runner-up qualified for the World Cup. As Argentina has not been past the group stages in the World Cup, the two teams have not met in the Olympic Football Tournament yet.

Notes

- Brazilian Football Confederation was established in 1914

See also

References

- Argentina - Brasil, clásico por excelencia Archived 16 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine by Eduardo Cántaro on Télam, 29 September 2014

- "Argentina 6-1 Brazil - March 05, 1940 / Friendlies 1940". footballdatabase.eu. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- Tilghan, John (27 August 2009). "Argentina-Brazil: South America's Biggest Rivalry". Bleacherreport. Archived from the original on 28 August 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- "Argentina in Brazil - The essence of football rivalry". fifa.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 6 June 2014. Archived from the original on 7 June 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- Duke, Greg. "Top 10 international rivalries". CNN. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Armbruster, Cassidy (10 July 2021). "Where does the rivalry between Argentina and Brazil come from?". AS. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- "World Football Elo Ratings". eloratings.net. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- Rajarshi (9 July 2021). "Argentina vs Brazil: One of the fiercest rivalries in International Football". Sportco. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- Fitzgerald, Daniel (14 September 2011). "Argentina vs. Brazil: The 12 Best Players of All-Time". Bleacherreport. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- Ambrosio, Tauan (15 November 2019). "Brazil & Argentina: Over 100 years of a great rivalry". Goal. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- Davison, Phil (15 March 2005). "Football: The Maradona diet: a gastric bypass, holy water and a pinch of salt". The Independent. London. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- "11v11". 11v11. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- "Southamerican Championship 1937". RSSSF.

- at Fifa. Last retrieved 17 November 2010.

- RSSSF. "Copa Julio Roca". Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- RSSSF. "Copa del Atlántico". Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- RSSSF. "Copa "ZH 35th Anniversary"". Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- RSSSF. "Copa Roberto Chery". Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- RSSSF. "Copa Confraternidad". Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- RSSSF. "Nations' Cup (Brazil 1964)". Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- RSSSF. "Australia Bicentenary Gold Cup (Australia 1988)". Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- RSSSF. "Copa Centenario de la A.F.A." Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- RSSSF. "Copa 50imo Aniversario de Clarín". Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- Gazeta de Noticias, 23 June 1908

- Correio de Manha, 12 September 1912

- Los orígenes de los clásicos con Brasil (1908-1914)" on Viejos Estadios blogsite

- ARGENTINA NATIONAL TEAM ARCHIVE by Héctor Pelayes on the RSSSF

- RSSSF Brasil. "Observations about the Brazilian National Team Archive". Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- RSSSF. "Copa Raúl Colombo". Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Diego y Pelé, los mejores de siempre on Página/12, 2000

- ¿Pelé o Maradona? ¿Quién logró más goles y títulos en mundiales y competiciones internacionales? at CNN, 24 Sep 2022

- LA RELACIÓN DE GARRINCHA Y PELÉ, UNA VERDAD INCÓMODA on Kodro Magazine

- 1988: DI STÉFANO - MARADONA, DOS GRANDES FRENTE A FRENTE at El Gráfico, 25 Nov 2020

- Neymar, el sucesor avalado por Pelé on Sport.es by Joaquim Piera, 31 Mar 2009

- Maradona: "Messi es mi sucesor", 20 Apr 2007

- CNNSI – "The Maradona-Pele furor". Last retrieved 31 May 2006.

- Miller, Nick (9 October 2015). "The 10 greatest rivalries in international football". espnfc.co.uk. ESPN FC. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- "Pelé still in global demand". CNN Sports Illustrated. 29 May 2002. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- Kissinger, Henry (1 April 2010). "The 2010 Time 100 Poll". Time. Archived from the original on 31 May 2000. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- Consulting, Bendoni. "Diego Armando Maradona (BEST PLAYER OF THE 20th CENTURY)".

- "Un diario inglés eligió a Maradona como el mejor jugador de la historia de los mundiales | Lima | Sociedad | el Comercio Peru". Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "FourFourTwo's 100 Greatest Footballers EVER: No.1, Diego Maradona". fourfourtwo.com. 25 November 2020.

- "CDS, Maradona meglio di tutti, batte anche Valentino Rossi | Tifo Napoli". Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- CNNSI – "The great FIFA swindle". Last retrieved 31 May 2006.

- CNNSI – "Split decision: Pele, Maradona each win FIFA century awards after feud" Last retrieved 31 May 2006.

- BBC – "Maradona, Pele in furious bust-up". Last retrieved 31 May 2006.

- BBC – "Maradona tackles Pele on TV show" Last retrieved 31 May 2006.

- "Diego Maradona was much better than Lionel Messi, says Pele". India Today.

- "El emotivo mensaje de apoyo de Maradona al 'Rey Pelé'". Nación Deportes. 10 April 2019.

- "Feuding no more, Pelé joins world in mourning Diego Maradona". AP NEWS. 20 April 2021.

- "Viejos Estadios: Sportivo Barracas".

- "Copa America's Classic Rivalry: Brazil vs. Argentina". 3 July 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "The Rivalry: Brazil X Argentina". netvasco.com. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- Argentina fue el último que le hizo 5 goles a Brasil a domicilio on Infobae, 8 July 2014

- Aquella patada de Jair a Salomón by Alfredo Relaño on El País, 4 July 2005

- Museo Dos Deportes – "O dia do desespero entre Brasil e Argentina" Archived 1 October 2002 at the Wayback Machine (in Portuguese). Last retrieved 31 May 2006.

- "Argentina v Brazil, 30 June 1974". 11v11.com. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- (in Spanish) http://www.laultima.com/noticia.php?id=11179&seccion=F%C3%BAtbol&idcategoria=7 Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Bellos, Alex (21 January 2005). "Brazil revive drug row after 15 years". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Copa América 1991 Final Pool – from RSSSF.

- The hand of the devil still rankles as the Copa reaches its climax.

- "Brazil 2-0 Argentina: Roberto Firmino and Gabriel Jesus send Selecao to Copa America final". Sky Sports. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- "Argentina 1-0 Brazil: Copa América final – as it happened | Copa América". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- Rsssf.com Archived 1 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

- Argentina vs. Brazil statistics by RSSSF

- Brazil vs. Argentina rivalry on Netvasco.com (in Portuguese)

- Argentina vs. Brazil September 5 2009 results