Copley Square

Copley Square /ˈkɒpli/,[1] is a public square in Boston's Back Bay neighborhood, bounded by Boylston Street, Clarendon Street, St. James Avenue, and Dartmouth Street. The square is named for painter John Singleton Copley. Prior to 1883 it was known as Art Square due to its many cultural institutions, some of which remain today.

| Copley Square | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp)   Clockwise from top: Statue of John Singleton Copley in front of Trinity Church and the Hancock, the fountain, Boston Public Library, Farmers market. | |

| Type | Public park |

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Area | 2.4 acres (0.97 ha) |

| Created | 1883 |

| Designer | Dean Abbott (1984) |

| Owned by | The City of Boston |

| Public transit access | Subway and bus; see "Transportation" |

Architecture

Several architectural landmarks are adjacent to the square:

- Old South Church (1873), by Charles Amos Cummings and Willard T. Sears in the Venetian Gothic Revival style

- Trinity Church (1877, Romanesque Revival), considered H. H. Richardson's tour de force

- Boston Public Library (1895), by Charles Follen McKim in a revival of Italian Renaissance style, incorporates artworks by John Singer Sargent, Edwin Austin Abbey, Daniel Chester French, and others

- The Fairmont Copley Plaza Hotel (1912) by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh in the Beaux-Arts style (on the site of the original Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

- The John Hancock Tower (1976, late Modernist) by Henry N. Cobb, at 790 feet (240 m) New England's tallest building

- The BosTix Kiosk (1992, Postmodernist), at the corner of Dartmouth and Boylston streets, by Graham Gund with inspiration from Parisian park pavilions[2]

Notable buildings later demolished:

- Peace Jubilee Coliseum[3] (1869, demolished the same year) A temporary wooden structure, seating fifty thousand, was built on St. James Park for the 1869 National Peace Jubilee. Replaced by World's Peace Jubilee Coliseum (1872), which was replaced by the Museum of Fine Arts.

- Second Church (1874, sold 1912, demolished by 1914) A Gothic Revival church by N. J. Bradlee.

- Chauncy Hall School (c. 1874, demolished 1908), a tall-gabled High Victorian brick school building on Boylston St. near Dartmouth Street.[4]

- Museum of Fine Arts (1876, demolished 1910) by John Hubbard Sturgis and Charles Brigham in the Gothic Revival style, was the first purpose-built public art museum in the world.

- S.S. Pierce Building, (1887, demolished 1958) by S. Edwin Tobey, "no masterpiece of architecture, [but] great urban design. A heap of dark Romanesque masonry, it anchored a corner of Copley Square as solidly as a mountain."[5]

- Hotel Westminster[6] (1897, demolished 1961), Trinity Place, by Henry E. Cregier;[7][8] now replaced by the northeast corner of the new John Hancock Tower. Razed in 1961 by owner John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company for a parking lot.[9]

- Grundmann Studios (1893, demolished 1917), home of the Boston Art Students Association (later known as the Copley Society), contained artist studios and Copley Hall, a popular venue for exhibitions, lectures and social gatherings.

Public art

- Statue of Phillips Brooks, Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1907–1910)

- The Kahlil Gibran Memorial,[10] Kahlil Gibran, nephew and godson of the poet (1977)

- The Tortoise and the Hare, Nancy Schön (1994)

- The Boston Marathon Centennial Monument, Mark Flannery (1994). Additions by Robert Shure and Robert Lamb (1996).[11]

- Statue of John Singleton Copley, Lewis Cohen (2002)

Public events

One of the most popular attractions in Copley Square is the Farmers Market, held Tuesdays and Fridays from May through November.[12] (During the 2023-2024 reconstruction of the park, the market is held in front of the Public Library on Dartmouth.)

Annual events include First Night activities and ice sculpture competition, the Christmas tree lighting, the Boston Book Festival, and, for several years, the Boston Summer Arts Weekend. The park's central location also makes it a natural gathering place for protests and vigils.

The water level in the fountain pool can be lowered, turning it into a stage for concerts and theatrical performances.

History

A significant number of important Boston educational and cultural institutions were originally located adjacent to (or very near) Copley Square, reflecting 19th-century Boston's aspirations for the location as a center of culture and progress.[13] These included the Museum of Fine Arts, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard Medical School, the New England Museum of Natural History (today's Museum of Science), Trinity Church, the New Old South Church, the Boston Public Library, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Massachusetts Normal Art School (today's Massachusetts College of Art and Design), the Horace Mann School for the Deaf, Boston University, Emerson College, and Northeastern University.

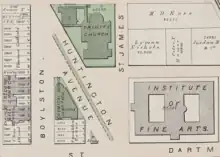

By 1876, with the completion of the Museum of Fine Arts, Walter Muir Whitehill noted that "Copley Square which — unlike the rest of the Back Bay — had never been properly or reasonably laid out, was beginning to stumble into shape".[14] But the land comprising the current square, bisected diagonally by Huntington Avenue, was still available for commercial development. The city purchased the larger triangle, then known as Art Square, in 1883 and dubbed it Copley Square.[note 1] The smaller plot, known as Trinity Triangle, was the subject of several lawsuits against the property owner, who planned to put up a six-story apartment building directly in front of Trinity Church. Foundations were laid but further construction was delayed by various injunctions.[16] The city council appropriated funds for purchase of the triangle in 1885.[17] Calls to close off Huntington between Dartmouth and Boylston streets began almost immediately, but that was not accomplished until 1968.[18]

In 1966, a proposal by the Watertown, Massachusetts, landscape design firm Sasaki, Dawson, DeMay was selected from 188 entrants in a national competition sponsored by the city and private development concerns. The design centered on a sunken terraced plaza, intended to separate the pedestrian from the noise and bustle of the surrounding streets, but it also isolated the square from the community. As the architecture critic Robert Campbell noted, "From the day it opened, it didn't work".[19]

In 1983 the Copley Square Centennial Committee, consisting of representatives of business, civic and residential interests, was formed. They announced a new design competition, funded by a grant of $100,000 from the National Endowment for the Arts. The winner, announced in May, 1984, was Dean Abbott of the New York firm Clarke & Rapuano.[20][21] The park was raised to street-level and a lawn and planting beds were added. The fountain, which had rarely functioned as intended, was re-configured. The updated park was dedicated on June 18, 1989, and received mixed reviews.[22]

By 2021 the park, now heavily used, was again in need of redesign; requirements included alleviating stress on existing trees, adding more trees, making the fountain safer, and prioritizing ease of maintenance. After a series of public meetings, the final proposal by Sasaki Associates was presented to the city in May, 2022.[23] Renovations began on July 20, 2023 and are expected to take sixteen months.[24]

The non-profit membership organization Friends of Copley Square was formed in 1992 as a successor to the Copley Square Centennial Committee. It raises funds for care of the square's plantings, fountain, and monuments, and also manages the Copley Square Charitable trust.[25]

The Boston Marathon foot race has finished at Copley Square since 1986.[26] A memorial celebrating the race's 100th running in 1996 is located in the park, near the corner of Boylston and Dartmouth streets. [27]

Unrealized projects

- 1874 A surveyor's map shows a "Chemical School, Inst. Tech." (never built) and four house lots on the larger triangle.

- 1894 A circular, sunken garden combining designs by Rotch & Tilden and Walker and Kimball, ringed with trees and marble balustrades, centered on a small fountain.[28]

- 1912 A plan by architect Frank Bourne eliminated the Huntington Avenue crossing and sunk the square 2.5 feet below street level. One version featured an enormous monumental column in the center of the plaza.[29]

- 1914 Landscape architect Arthur Shurtleff envisioned a circle of trees around the Brewer Fountain, which would be moved from Boston Common.[30]

- 1927 A proposal for a State War Memorial, from plans by Guy Lowell, placed a large, cylindrical granite structure in a basin. The inner chamber rose fifty feet to a domed ceiling and the memorial was topped with bronze representation of Hope.[31]

- 2012 A juried competition held by SHIFTBoston invited designs for creative illumination.[32] First prize was awarded to the firm Khoury Levit Fong for their conceptual chandelier of LEDs suspended over the square.[33]

Boston Marathon bombing

On April 15, 2013, around 2:50 pm (about three hours after the first runners crossed the line) two bombs exploded—one near the finish line near the Boston Public Library, the other some seconds later and one block west. Three people were killed and at least 183 injured, at least 14 of whom lost limbs.

Transportation

Copley is served by several forms of public transportation:

- Copley Station on the MBTA Green Line

- Several MBTA bus routes; the square is a major transfer point and terminal for several local and express routes

- Logan Express to Logan International Airport

- Nearby Back Bay station for MBTA Orange Line, MBTA Commuter Rail, and Amtrak

Major roads:

Notes

- Some local wits suggested "Copley Skew" or "Copley Corners" as more appropriate for the non-square shape.[15] Others were against honoring a man who had left America in 1774 and never returned.

References

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "The Boston History Project: Copley Square with Anthony Sammarco". YouTube.

- Mary Melvin Petronella, ed., Victorian Boston Today: Twelve Walking Tours (Northeastern University Press, 2004), 69, available online, access September 9, 2012

- "Old Boston Coliseum, 1869". CelebrateBoston. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- "259 Boylston Street, Chauncey Hall School, ca. 1874–90". Tufts Digital Library. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- Robert Campbell and Peter Vanderwarker. Coming into Copley. Boston Globe. Mar 26, 2006. p. BGM 16.

- Strahan, Derek (January 26, 2016). "Hotel Westminster, Boston". Lost New England. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- "Chicago Man's Reputation". Boston Evening Transcript. Feb 3, 1900. p. 7. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Shand-Tucci 1999, p. 102

- "Old Westminster Hotel to be Razed for Parking Lot". The Boston Globe. December 2, 1960.

- "The Khalil Gibran Memorial". Boston Literary District. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- "Boston Marathon Memorial". publicartboston.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Copley Square Farmers Market". Mass Farmers Markets. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- Douglass Shand-Tucci, The Gods of Copley Square, lecture series, 2009, sponsored by Back Bay Historical/Boston-centric Global Studies and the New England Historical Genealogical Society

- Whitehill 1968, p. 171

- "Copley Skew". Boston Evening Transcript. May 15, 1885. p. 4.

- "Trinity Objects to Bachelors' Hall as Neighbor". The Boston Globe. September 24, 1884. p. 3. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- "The Common Council". Boston Evening Transcript. January 2, 1885. p. 4. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- Campbell, Robert; Vanderwarker, Peter (1992). Cityscapes of Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. p. 74. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- Campbell, Robert (August 9, 1983). "Copley Sq. may come back to life". The Boston Globe. p. 43. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- "Dean Abbott". The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- Pokorny 2002, pp. 12–13

- Campbell, Robert (June 11, 1989). "The newest Copley Square is better, but...". The Boston Globe. p. 225.

- "City of Boston Releases Design Updates for Copley Square". sasaki.com. May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- "Improvements to Copley Square Park". boston.gov. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- Pokorny 2002, pp. 43–44

- Powers, John (April 16, 2010). "Evolution of the Boston Marathon finish line". Boston Globe. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- "100 Public Artworks" (PDF). Boston Marathon Memorial. Boston Art Commission. p. 3. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Copley Sq Embellishment as Planned". The Boston Globe. June 14, 1894. p. 4. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- "Copley Square as Rearranged". Boston Evening Transcript. October 26, 1912. p. 22. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- "Copley Square as It Probably Will Be --- The Semi-Official Plan". Boston Evening Transcript. March 13, 1914. p. 2. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- "Recommends Copley Sq as Site for State's World War Memorial". The Boston Globe. February 28, 1927. p. 12. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- "Glow Competition". SHIFTBoston. 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- "GLOW/SHIFT Boston Copley Square Competition". cargocollective.com/khourylevitfong. 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

Sources

- Pokorny, Margaret, ed. (October 23, 2002). Copley Square: The Story of Boston's Art Square (PDF). Boston: Friends of Copley Square. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- Shand-Tucci, Douglass (1999). Built in Boston: City and Suburb 1800–2000. Foreword by Walter Muir Whitehill (Revised and Expanded ed.). Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1-55849-201-1. LCCN 99016750. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- Whitehill, Walter Muir (1968). Boston: A Topographical History (Second, enlarged ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-07951-5. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

Further reading

- Aldrich, Megan (1994). Gothic Revival. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-2886-2.

- Bunting, Bainbridge (1967). Houses of Boston's Back Bay: An Architectural History, 1840-1917. Cambridge: Belknap Press, an imprint of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-40901-9.

- Forbes, Esther (1947). The Boston Book. Photographs by Arthur Griffin. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 851279970.

- Kay, Jane Holtz (1999). Lost Boston (Expanded and updated ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-96610-5.

- Shand-Tucci, Douglass. "The Gods of Copley Square: Dawn of the Modern American Experience, 1865-1915", www.backbayhistorical.org/Blog, 2009. All chapters archived at Open Letters Monthly.

- Shand-Tucci, Douglass. "Renaissance Rome and Emersonian Boston: Michelangelo and Sargent, between Triumph and Doubt", Anglican Theological Review, Fall 2002, 995–1008.

- "Greetings from Copley Square: A Chronology in Postcards", Exhibitions, Boston Public Library, 2010, archived from the original on July 23, 2014

External links

- Copley Square Farmers' Market

- Friends of Copley Square

- Boston Public Library Copley Square Collection – via archive.org

- Boston Streetcars: Copley Square A history of public transportation around and through Copley Square

- View of Copley Square, 1974 Photograph by Nicholas Nixon of the first iteration of the plaza with the John Hancock tower in its "plywood palace" phase.

- Copley Connect pilot project Held in June 2022, the city closed one block of Dartmouth street to create a plaza. "For the first time in its history, Copley Square was unified as a grand civic space, bookended by Boston Public Library's McKim Building and H.H. Richardson's Trinity Church."