Copyright law of Canada

The copyright law of Canada governs the legally enforceable rights to creative and artistic works under the laws of Canada. Canada passed its first colonial copyright statute in 1832 but was subject to imperial copyright law established by Britain until 1921. Current copyright law was established by the Copyright Act of Canada which was first passed in 1921 and substantially amended in 1988, 1997, and 2012. All powers to legislate copyright law are in the jurisdiction of the Parliament of Canada by virtue of section 91(23) of the Constitution Act, 1867.

| Part of a series on |

| Canadian law |

|---|

|

| Sources |

|

| Core areas |

| Other areas |

| Courts |

| Education |

History

Colonial copyright law

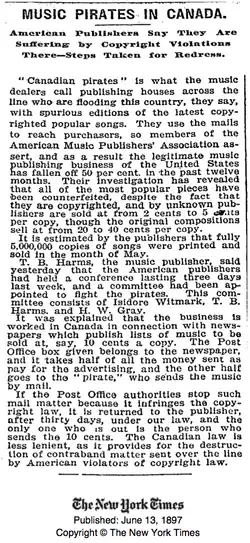

It is unclear to what extent British copyright law, or imperial law, starting with the 1709 Statute of Anne, applied to its colonies (including Canada),[1] but the House of Lords had ruled in 1774, in Donaldson v Beckett, that copyright was a creation of statute and could be limited in its duration. The first Canadian colonial copyright statute was the Copyright Act, 1832, passed by the Parliament of the Province of Lower Canada,[2] granting copyright to residents of the province. The 1832 Act was short, and declared ambitions to encourage emergence of a literary and artistic nation and to encourage literature, bookshops and the local press. After the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada (Ontario and Quebec) were reunified to form the Province of Canada, the 1832 Act was repealed and with minor changes enacted as the Copyright Act, 1841.[3][4]

The 1841 Act only granted copyright in books, maps, charts, musical compositions, prints, cuts and engravings. Copyright was only awarded if it was registered and a copy of the work deposited in the office of the registrar of the province before publication. The author or creator was required to be resident in the province in order to obtain copyright under the Act, though the Act was unclear on whether the work needed to have been first published in the Province. The objective of the colonial copyright statutes was to encourage the printing of books in Canada, though this was not made explicit to avoid conflict with imperial copyright law, which was primarily designed to protect English publishers. Britain forcefully demanded guarantees that British and Irish subjects were eligible for protection under Canadian colonial copyright law in the same way residents of the Canadian colony were.[5]

One year after Canada passed the 1841 act, the UK Parliament passed the Copyright Act 1842. The statute explicitly applied to "all Parts of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the Islands of Jersey and Guernsey, all Parts of the East and West India, and all the Colonies, Settlements, and Possessions of the Crown which now are or thereafter may be acquired". Any book published in London would therefore be protected by copyright law in the entire British Empire, including Canada.[4] The 1842 Act had an immediate impact on Canada and became infamous because it effectively prohibited the importation and sale of reprints of any book under British copyright printed in other countries. Previously Canada had mostly imported books from the United States, but it was now unlawful for Canadian merchants to engage in this trade. Instead merchants were required to import books under British copyright from printers in Britain, though British market prices were unaffordable for most residents of Canada. As British publishers systematically refused to license books for printing to Canadian printers, the Canadian Government questioned the responsible self-government arrangement.[6] In a provocative move Canada passed An Act to extend the Provincial Copyright Act to Persons Resident in the United Kingdom in 1847, granting British authors protection only if their works had been printed and published in the Province of Canada.[7] The 1841 and 1847 statutes were subject to minor revision in 1859 and the requirement for the works to be printed in Canada, buried in the text, was later noticed and denounced by the imperial British government.[5]

Confederation

Upon Confederation, the British North America Act, 1867 granted the federal government power to legislate on matters such as copyright and patents. In 1868 the Parliament of Canada passed the Copyright Act of 1868,[8] which granted protection for "any person resident in Canada, or any person being a British subject, and resident in Great Britain or Ireland."[9] It re-established the publication requirements of the 1847 statute, prompting demand from the British government that Canada should revise its laws so as to respect imperial copyright law.[10] Under Imperial copyright London printers had a monopoly and attracted most authors from the colonies to first publish with them because imperial copyright law granted protection in all colonies. London printers refused Canadian printers the license to print books first published in London and authors had little incentive to first publish in Canada, as colonial copyright law only granted protection in Canada. The Canadian government sought to further strengthen the Canadian print industry with an 1872 bill that would have introduced a projected licensing scheme that allowed for a reprinting of books under foreign copyright in exchange for a fixed royalty. The British government opposed the bill and it never received royal assent.[11]

In order to encourage the local printing and publishing industry Canada made a number of diplomatic and legislative efforts to limit the effects of the 1842 Imperial Act. In a compromise arrangement Canada passed the Copyright Act, 1875,[12] which provided for a term of twenty-eight years, with an option to renew for a further fourteen years, for any "literary, scientific and artistic works or compositions" published initially or contemporaneously in Canada, and such protection was available to anyone domiciled in Canada or any other British possession, or a citizen of any foreign country having an international copyright treaty with the United Kingdom, but it was contingent on the work being printed and published (or reprinted and republished) in Canada.[13] By registering under the Canadian Act, British and foreign publishers gained exclusive access to the Canadian market by excluding American reprints.[9]

In 1877, the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled that the Imperial Act of 1842 continued to have effect in Canada, despite the passage of the Canadian Act of 1875.[14] This effectively meant that Canadian copyright was a local scheme, whereas Imperial copyright conferred general protection throughout the British Empire.[15] The application of Imperial copyright was strengthened by the earlier decision of the House of Lords in Routledge v Low,[16] which declared that residence of an author, no matter how temporary, anywhere in the British dominions while his book was being published in the United Kingdom, was sufficient to secure it. As the United States was not then a signatory to an international copyright treaty (thus rendering its citizens ineligible for Canadian copyright), many Americans took advantage of this ruling by visiting Canada while their books were being published in London (and thereby obtaining Imperial copyright).[17]

There were other significant differences between the Canadian and Imperial régimes:[9]

| Provision | Copyright Act, 1875 (Canada) | Copyright Act 1842 (Imperial) |

|---|---|---|

| Term | Initial term of 28 years, with option to renew for another 14 years | Life of the creator plus 7 years, or 42 years from publication (whichever was greater) |

| Registration of copyright | Required for grant of copyright | Required in order to sue or claim copyright infringement |

| Copyright notice required | Yes | No |

Under the UK's Copyright Act 1911, the Parliament of Canada was granted authority to either extend its application to Canada or to repeal (subject to the preservation of all legal rights existing at the time of such repeal) any or all enactments passed by the Imperial Parliament (including the Act of 1911) so far as operative within the Dominion. Canada opted to exercise the latter choice, and, upon passage of the Copyright Act, 1921, it assumed complete jurisdiction over copyright and Imperial legislation in the matter ceased to have effect.[18]

Canada did not join the Buenos Aires Convention of 1910; adhered to by most Pan-American countries

Copyright Act, 1921

The Copyright Act, 1921, came into force in 1924. Though Canada was no longer subject to imperial copyright law, it was closely modelled on the UK Copyright Act 1911:

- the term of copyright was extended to 50 years after the creator's death[19] (but, where a work was not yet published at the time of death, its term was extended to 50 years after publication)[20]

- sound recordings were protected "as if such contrivances were musical, literary or dramatic works"[21]

- in the case of an engraving, photograph or portrait, the initial owner of the copyright was the person who commissioned the plate or other original[22]

- any remaining rights (if any) at common law were abolished[23]

Following the UK Carwardine case,[24] rights in performer's performances were also held to exist under the Canadian Act (although they were never enforced). This was abolished in 1971.[25]

New technological developments and the emergence of computers, photocopiers and recording devices led to a recognition that copyright law needed to be updated. Between 1954 and 1960 the Royal Commission on Patents, Copyright, and Industrial Design, known as the Ilsley Commission, published a series of reports.[26] Its brief was "to enquire as to whether federal legislation relating in any way to patents of invention, industrial designs, copyright and trade-marks affords reasonable incentive to invention and research, to the development of literary and artistic talents, to creativeness, and to making available to the Canadian public scientific, technical, literary and artistic creations and other adaptations, applications and uses, in a manner and on terms adequately safeguarding the paramount public interest."[27][28]

Reform (1988–2012)

Between 1977 and 1985, a series of reports and proposals were issued for the reform of Canadian copyright law.[27][29][30]

Eventually a copyright reform process was initiated in two phases: Phase one was started in 1988 and saw several amendments to the Copyright Act. Computer programs were included as works protected under copyright, the extent of moral rights was clarified, the provision for a compulsory license for the reproduction of musical works was removed, new licensing arrangements were established for orphan works in cases where the copyright owner could not be found, and rules were enacted on the formation of copyright collecting societies and their supervision by a reformed Copyright Board of Canada.[27]

Phase two of the reform took place in 1997 and saw the Copyright Act amended with a new remuneration right for producers and performers of sound recordings when their work was broadcast or publicly performed by radio stations and public places such as bars. A levy was introduced on blank audio tapes used for private copying and exclusive book distributors were granted protection in Canada. New copyright exceptions were introduced for non-profit educational institutions, libraries, museums, broadcasters, and people with disabilities, allowing them to copy copyrighted works in specific circumstances without the permission of the copyright owner or the need to pay royalties. Damages payable for copyright infringement and the power to grant injunctions were increased, and the 1997 reforms introduced a mandatory review of the Copyright Act.[27] Copyright in unpublished works was limited to 50 years after the creator's death, but unpublished works by creators who died after 1948 but before 1999 retain their copyright until 2049.[31]

After becoming a signatory country of World Intellectual Property Organization Internet Treaties in 1996, Canada implemented its terms in 2012 with the passage of the Copyright Modernization Act.[32] The 2012 act focuses on anti-circumvention provisions for technical protection measures, the protection of authors' rights, and the public's rights concerning the copying of legally obtained materials.[33] During consideration of the bill, many groups publicly stated their opposition to its digital lock specifications,[34] arguing that such measures infringed on legitimate usage of copyright holding.[35] The government rejected many of these criticisms of the TPM provisions.[36]

Copyright review and consultation process (2017–2019)

The 2012 amendments to the Copyright Act included an updated provision for a recurring 5-year parliamentary review of the Act. Section 92 of the Act mandates the establishment of a Senate or House of Commons committee for the purpose of carrying out this review.[37] On December 14, 2017, the Minister of Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada and the Minister of Canadian Heritage announced plans to commence a parliamentary review of the Copyright Act.[38] The Canadian House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology was given charge of the parliamentary review. The Committee collected 192 briefs (written submissions) and heard testimony from 209 witnesses, concluding its consultation process in December 2018.[39] Submissions were received from a wide variety of interested parties, including associations representing students, universities, libraries and researchers; unions, associations and collective management organizations representing writers, artists, and performers; corporations from the communications sector; associations representing the film, theatre and music industries; media organizations; government departments; and representatives of the Copyright Board of Canada.[39] The final report of the Committee was released in June 2019 and contained 36 recommendations.[40]

As part of the review, the Committee also requested that a parallel consultation be conducted by the Canadian House of Commons Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage, which announced its launch of a Study on Remuneration Models for Artists and Creative Industries in the Context of Copyright on April 10, 2018.[41] The testimony of Canadian musician Bryan Adams given on September 18, 2018 as part of this consultation garnered significant media attention.[42] Adams proposed an amendment to s. 14(1) of the Copyright Act to change the period after which an assignment of copyright would revert to the author 25 years after assignment, rather than 25 years after the death of the author.[43] Adams invited law professor Daniel Gervais to present arguments in support of his proposal. One of the rationales put forward by Professor Gervais was to permit a reasonable period for those assigned copyright to exploit the commercial interest in a work and recoup their investment, while at the same time incentivizing and supporting the creativity of artists by allowing them to regain control within their lifetime.[43]

In addition to the legislated parliamentary review of the Copyright Act, separate consultations were held with respect to the Copyright Board of Canada. In August 2017, Innovation Science and Economic Development Canada, the Department of Canadian Heritage, and the Copyright Board of Canada issued "A Consultation on Options for Reform to the Copyright Board of Canada," a document outlining the potential scope and nature of reforms to the legislative and regulatory framework governing the Copyright Board of Canada and soliciting comments from the public.[44] The consultation period concluded September 29, 2017. A fact sheet published by Innovation Science and Economic Development Canada summarized the key issues raised in the consultation and announced a 30% increase to funding to the Board to address significant time delays in tariff-setting.[45] Bill C-86, an Act implementing provisions of the 2018 federal budget, received royal assent on December 13, 2018.[46] The Act implemented amendments to the Copyright Act in relation to the administration of the Copyright Board.[46]

While the Copyright Act review was being carried out, trade negotiations leading to the USMCA were ongoing. Law professor Michael Geist noted that the terms of the USMCA relating to intellectual property would need to be taken into consideration by the review Committee and would require changing provisions of the Copyright Act that were amended in the last round of copyright reform in 2012.[47]

Extension of copyright for certain sound recordings (2015)

From June 23, 2015, the rules governing copyright protection were modified to provide that copyright in unpublished sound recordings created on or after that date would last for 50 years after fixation, but if the sound recording is published before the copyright expires, the applicable term would then be the earlier of 70 years from its publication or 100 years from fixation.[48] By implication, this will also extend the copyright for performer's performances contained in such recordings.[48]

Extension of copyright for published pseudonymous or anonymous works (2020)

From July 1, 2020, the rules governing copyright protection for published pseudonymous or anonymous works were extended by 25 years. This extension did not have the effect of reviving a copyright.[49]

Extension of copyright term

Under the conditions of the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement[50] the copyright term would have been extended to life plus 70 years. Although it was signed by Canada in February 2016, this treaty was not ratified, and did not go into effect. Under its successor, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, Canada's copyright term did not change.[51] Canada continued to hold to the Berne Convention standard, which is life of the author plus 50 years.[52] In addition the Berne Convention provides that extensions of terms will not have the effect of reviving previously expired copyrights. Article 14.6 of the TRIPs Agreement makes similar provision for the rights of performers and producers in sound recordings.

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement proposed the extension of Canada's copyright term to life plus 70 years, while performances and sound recordings will be protected for 75 years. It has been signed and ratified.[53] This agreement replaces the North American Free Trade Agreement.[54] In its May 2019 report, the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage has recommended that the extension be implemented.[55] The bill introduced to implement the USMCA did not include the extension language. This was reportedly done to allow a transition period to determine the best way to meet the extension obligation.[56] A commitment to the obligation was included in the 2022 Canadian federal budget.[57]

The extension of Canada's copyright term to life plus 70 years was formalized via amendment to the Copyright Act on 23 June 2022, which came into force on 30 December 2022, but did not revive expired copyright.[58][59]

The Writers' Union of Canada has expressed strong support for copyright extension.[60] Canadian singer/songwriter Bryan Adams argues that extensions may increase profits to intermediaries such as major record labels, but do not benefit the actual creators of copyrighted works. He believes that copyright law should include a change to revert rights back to the creator after 25 years.[61] Proponents of a strong public domain argue that extending copyright terms will further limit creativity and argue that “there is no evidence to suggest that the private benefits of copyright term extensions ever outweigh the costs to the public.”[62] The Canadian Confederation of Library Associations disagrees with the extension. But it believes some of the problems can be mitigated by, among other things, requiring each work be formally registered in order to receive the 20 year extension.[63]

Rights conferred

The Act confers several types of rights in works:

- copyright

- moral rights

- neighbouring rights

Copyright includes the right to first publish, reproduce, perform, transmit and show a work in public. It includes other subsidiary rights such as abridgment and translation.[64]

Moral rights were instituted upon Canada's accession to the Berne Convention, and they possess several key attributes: attribution, integrity and association. They allow the author of a work to determine how it is being used and what it is being associated to.[64]

Neighbouring rights — generally discussed in the music industry (e.g. performer's rights, recording rights) — are a series of rights relating to one piece of work, and were established upon Canada's accession to the Rome Convention. They do not relate to the creative works themselves, but to their performance, transmission and reproduction.[64]

Similar protection is extended to copyright holders in countries that are parties to:

Protected works

A work must be original and can include literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works or compilations. Copyright is granted the moment the work is created and does not distinguish work of a professional or that of an amateur. There is also no distinction between for profit or commercial use or for hobby purposes. Literary work includes anything that is written, such as speeches, essays and books and may be in any form. However, a short string of words or spontaneous speech is not covered. Dramatic works include the characters, scenes, choreography, cinematography, relationship between characters, dialogue and dramatic expression. Artistic works include sculptures, paintings, photographs, charts and engravings. Musical works include any musical compositions with or without words. Unexpressed ideas are not protected work.[64]

Copyright also extends to incomplete creations such as proposals, treatments and formats, and infringement can occur when subsequent audiovisual works use their elements without ever actually literally copying them.[65]

It is unclear whether the subjects in interviews have copyright in the words they utter (and thus be considered to be their authors), as the courts have not definitively ruled on the issues of originality and fixation in such cases.[66] However, in Gould Estate v Stoddart Publishing Co Ltd, the Ontario Court of Appeal noted that "offhand comments that [the interviewee] knew could find their way into the public domain ... [were] not the kind of disclosure which the Copyright Act intended to protect."[67]

Ownership of a creative work may be assigned to a corporation or other employer as part of an employment contract. In such a cases, the employer retains ownership of the creative work even after the contract ends. The new copyright owner is therefore free to make changes to the finished product without the creator's consent.[68]

A creative employee, meanwhile, may continue to use his or her experience, expertise, and memory to create a similar product after the conclusion of a contract. In 2002, the Ontario Court of Appeal upheld a literal interpretation of the word "copy" and found that a software engineer's creation of a "similar" product from memory did not constitute infringement of his former employer's copyright.[69]

Fair dealing

Unauthorized copying of works can be permissible under the fair dealing exemption. In CCH Canadian Ltd. v. Law Society of Upper Canada,[70] the Supreme Court of Canada made a number of comments regarding fair dealing, and found that the placement of a photocopier in a law library did not constitute an invitation to violate copyright. In Alberta (Education) v Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), the Court further clarified this exemption from copyright law in the context of education, finding that a teacher may photocopy a brief excerpt from a textbook in circumstances where it would be impractical to purchase a text book for each student.

Fair dealing is to be examined on a case-by-case basis. The purpose of the dealing, character of the dealing, amount of the dealing, alternatives of the dealing, nature of the work and effect of the dealing are factors that can contribute to fair dealing. Those favouring a broad interpretation of fair dealing argue there ought to be reasonable unauthorized reproduction of works because it facilitates creativity and free expression. They also argue that fair dealing provides reasonable access to existing knowledge. Those arguing that fair dealing ought to be more restrictive and specific state that fair dealing will reduce revenue to those creating works. They also argue the reproduction of works and sends a wrong message to the public that works are free as long as it falls under this banner. Their economic argument is that fair dealing should not compensate for the market's inability to meet the demand for public knowledge.[71]

The impact of the CCH analysis has been problematic, and many users have attempted to simplify the administration through the adoption of guidelines quantifying what amounts of a work may be acceptable. The Federal Court of Canada pointed out in 2017, when invalidating guidelines that had been adopted by York University,[72] that this is not an easy exercise. Emphasis was given to the fact that the CCH six-factor test was the second part of a two-stage analysis in which a user must first identify whether a use was allowed before then assessing whether dealing is fair, and stressed that users must not conflate the two stages.[73]

General rule

Subject to other provisions of the Act, a work will fall into the public domain:[74]

- 50 years after publication, in nearly all cases, if it was subject to Crown copyright.[75]

- 70 years after the death of its creator.

- if the author is unknown, 75 years after publication or 100 years after its creation (whichever is less), otherwise (if not published) 75 years after its creation.[76]

- if it is a communications signal, 50 years after the signal is broadcast.

In all cases:

- copyright expires at the end of the calendar year in which the relevant date falls.

- in the case of joint authorship of a work, copyright extends from the death of the last surviving author.[77]

- in the case of a pseudonymous or anonymous work where one or more of the creators have become commonly known, the normal rules governing authorship apply.[78]

- where the author is the first owner of the copyright and has subsequently assigned it (other than by will), the assignment will only extend to 25 years after the author's death, after which copyright will revert to the author's estate.[79]

- moral rights in a work have the same term as the copyright in it, and cannot be assigned (other than by inheritance), but can be waived in whole or in part.[80]

Posthumous works

Before the 1999 reform of the Act, works that were published after the death of the author were protected by copyright for 50 years after publication, thus granting perpetual copyright to any work not yet published. This was revised so that protection is limited as follows:

| Where an author dies... | with an unpublished work that is... | Term of copyright |

|---|---|---|

| before December 31, 1948 | published before December 31, 1998 | 50 years from date of publication |

| not published on or before December 31, 1998 | protected until December 31, 2003 | |

| on or after December 31, 1948 | protected until December 31, 2049 | |

| after December 31, 1998 | protected until 50 years after the end of the year of death | |

Photographs

The Copyright Modernization Act, which came into force on November 7, 2012, altered the rules with respect to the term of copyright with respect to photographs so that the creator holds the copyright and moral rights to them, and the general rule of life plus 50 years thereafter applies all such works. However, there are two schools of thought with respect to how copyright applies to photographs created before that date:

- Some commentators believe that the transitional rules implemented in the 1999 reform still apply.[82]

- Others assert that such rules were ousted when the 2012 act came into force, and that the general rule under s. 6 of the Copyright Act governs.[83] This may also have had the collateral effect of reviving copyright in some works that had previously lapsed.[83]

The differences between the two points of view can be summarized as follows:

| 1999 transitional rules remain in effect | 1999 transitional rules ceased to have effect | |

|---|---|---|

| created before 1949 | copyright ceased to have effect after 1998 | In all cases (except where Crown copyright applies):

|

| created by an individual after 1948 | general rule applies | |

| where the negative is owned by a corporation, and the photograph was created after 1948 and before November 7, 2012 | if the majority of its shares are owned by the creator of the photograph, the general rule applies | |

| in all other cases, the remainder of the year in which the photograph was made, plus a period of 50 years | ||

There is some controversy as to the legal status of photographs taken before 1949 in the first scenario, as it can be argued that the current practice of statutory interpretation in the courts would hold that copyright protection was moved to the general rule by the 1999 reform to such photographs that were taken by individuals or creator-controlled corporations.[84] In any case, this argument states that the 2012 act effectively removed all such special rules that were formerly contained in s. 10 of the Copyright Act.[84]

There has not yet been any jurisprudence in the matter, but it is suggested that previous cases, together with the 2012 act's legislative history, may favour the second scenario.[85]

Sound recordings and performance rights

Before September 1, 1997, copyright in sound recordings was defined as being in "records, perforated rolls and other contrivances by means of which sounds may be mechanically reproduced."[86] From that date, they are defined as being "a recording, fixed in any material form, consisting of sounds, whether or not of a performance of a work, but excludes any soundtrack of a cinematographic work where it accompanies the cinematographic work."[87] Subject to that observation, such recordings will fall into the public domain:

- for sound recordings created before 1965, 50 years after fixation, but if the sound recording is published before the copyright expires, 50 years after its publication (but only where copyright expires before 2015).[48]

- for sound recordings created otherwise, 50 years after fixation, but if the sound recording is published before the copyright expires, the earlier of 70 years from its publication or 100 years from fixation.[48]

Performance rights (in their current form) subsisting in sound recordings did not exist until 1994 (with respect to their producers) or 1996 (with respect to their performers).[88] Performer's performances that occurred in a WTO member country only received protection after 1995.[88] Effective September 1, 1997, performance rights were extended to performances captured on communication signals.[89] Subject to that, such performances will fall into the public domain:

- for performer's performances before 1962, the earlier of 50 years after its first fixation in a sound recording, or 50 years after its performance, if not fixed in a sound recording (but only where copyright expires before 2012).

- for performer's performances created on or after 1962 but before 2015, 50 years after the performance occurs, but (a) if the performance is fixed in a sound recording, 50 years after its fixation, and (b) if a sound recording in which the performance is fixed is published before the copyright expires, the earlier of 50 years after publication and 99 years after the performance occurs (but only where copyright expires before 2015).[48]

- for performer's performances created otherwise, 50 years after the performance occurs, but (a) if the performance is fixed in a sound recording, 50 years after its fixation, and (b) if a sound recording in which the performance is fixed is published before the copyright expires, the earlier of 70 years after publication and 100 years from fixation.[48]

Anti-circumvention

Any circumvention of technical protection measures designed to protect a copyrighted work is unlawful, even if the action was not for the purpose of copyright infringement. The marketing and distribution of products meant to breach technical protection measures is also unlawful. Exceptions exist in situations when the circumvention is for the purposes of accessibility, encryption research, privacy and security testing, reverse engineering to achieve software compatibility (if it is not already possible to do so without breaching TPMs),[90] the creation of temporary recordings by broadcasters, and for law enforcement and national security purposes.[91][92]

The federal court adopted a wide interpretation of the anti-circumvention rules in the case of Nintendo of America v. Go Cyber Shopping, asserting that alongside their use for enabling the use of pirated copies of software for them, a retailer of modchips for video game consoles could not use the availability of homebrew software as a defence under the interoperability provision, because Nintendo offers official manner for developers to create games for their platforms, thus making it possible to achieve interoperability without breaching TPMs.[90]

Administration

The Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO), part of Industry Canada, administers intellectual property laws concerning the registration of patents, trade-marks, copyrights, industrial designs and integrated circuit topographies.[93]

Copyright Board

The Copyright Board of Canada is an evidence based decision making tribunal that has four primary functions: (1) establish royalties users must pay for copyrighted works; (2) establish when the collection of such royalties is to be facilitated by a "collective-administration society"; (3) oversee agreements between users and licensing bodies; and (4) grant users licenses for works when the copyright owner cannot be located.[94]

Collection of royalties and enforcement of copyright is often too costly and difficult for Individual owners of works. Therefore, collectives are formed to facilitate the collection of fees.[95] Collectives may file proposed tariff with the Copyright Board or enter into agreements with users.

| Collective | Function |

|---|---|

| Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada | Canadian composers and lyricist assign performance and communication rights to the Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers in Canada (SOCAN), which then sells blanket licenses of its repertoire. The licensing fees collected are distributed back to Canadian composers and lyricists.[95] |

| Canadian Private Copying Collective | To cope with the large number of private copying of audio recordings, provisions requiring the collection of levies on blank audio recording media were implemented in 1997. The collected proceeds are distributed to Canadian and foreign composers, but only Canadian recording makers and performers may enforce the levies,[95] which are collected by the Canadian Private Copying Collective. As of 2013, the levy imposed for private copying is 29¢ for each CD-R, CD-RW, CD-R Audio or CD-RW Audio.[96] |

| Access Copyright | Access Copyright is the collective for English-language publishers, and its recent focus has been towards the education and government sectors. Its tariff replaces the former Canadian Schools/Cancopy License Agreement. The initial 2005–2009 tariff, which fixed the royalty at $5.16 per full-time equivalent student,[97] was the subject of extensive litigation [98] which was finally resolved by the Supreme Court of Canada in Alberta (Education) v. Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright),[99] after which the rate was reduced to $4.81.[100] Proposed tariffs for subsequent years are still pending at the Copyright Board.[101] |

See also

References

Notes

- Moyse 2008, p. 111.

- An Act for the protection of Copy Rights, S.L.C. 1832, c. 53

- An Act for the protection of Copy Rights in this Province, S.Prov.C. 1841, c. 61

- Moyse 2008, pp. 110–111.

- Moyse 2008, pp. 111–112.

- Moyse 2008, p. 108.

- An Act extend the Provincial Copy-Right Act to persons resident in the United Kingdom, on certain conditions, S.Prov.C. 1847, c. 28

- The Copyright Act of 1868, S.C. 1868, c. 54

- Bannerman 2013, ch. 3.

- Moyse 2008, pp. 113–114.

- Moyse 2008, p. 114.

- The Copyright Act of 1875, S.C. 1875, c. 38

- Copyright Act, 1875, ss. 3–5

- Smiles v. Belford, 1 O.A.R. 436, held to have been properly decided in Durand et Cie v. La Patrie Publishing Co., 1960 CanLII 63 at p. 656, [1960] SCR 649 (24 June 1960)

- Easton, J. M. (1915). "III: Local Copyright Laws of British Colonies and Possessions". The law of copyright, in works of literature, art, architecture, photography, music and the drama: Including chapters on mechanical contrivances and cinematographs, together with international and foreign copyright, with the statutes relating thereto (5th ed.). London: Stevens and Haynes. pp. 339–345.

- Routledge v. Low, (1868) 3 LTR 100, expanding upon its previous ruling in Jefferys v Boosey (1854) 4 HLC 815, 10 ER 681 (1 August 1854)

- Dawson 1882, pp. 20–21.

- Moyse 2008, pp. 114–115.

- Copyright Act, 1921, s. 5

- Copyright Act, 1921, s. 9

- Copyright Act, 1921, s. 4(3)

- Copyright Act, 1921, s. 11(1)(a)

- Copyright Act, 1921, s. 41(3), Schedule

- Gramophone Co Ltd v Stephen Carwardine & Co, 1 Ch 450 (1934).

- noted in Performance Rights in Sound Recordings. Washington, D.C.: United States House Committee on the Judiciary. 1978. pp. 216–219.

- including Report on Copyright (PDF). Ottawa: Royal Commission on Patents, Copyright, Trade Marks and Industrial Designs. 1957.

- Makarenko, Jay (13 March 2009). "Copyright Law in Canada: An Introduction to the Canadian Copyright Act". Judicial System & Legal Issues. Mapleleafweb. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- "Patents, Copyright and Industrial Designs, Royal Commission on". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- Erola & Fox 1984; Keyes & Brunet 1977.

- A Charter of Rights for Creators — Report of the Subcommittee on the Revision of Copyright. Ottawa: Supply and Services Canada. 1985.

- Copyright Act, s. 7(3)

- Copyright Modernization Act, S.C. 2012, c. 20

- Christine Dobby (September 29, 2011). "Canada's copyright overhaul and the digital locks controversy". Financial Post.

- Copyright Act, ss. 41–41.21, inserted by the Copyright Modernization Act

- "Responding to Bill C-32: An Act to Amend the Copyright Act" (PDF). Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences. November 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- "Change and the Copyright Modernization Act". Barry Sookman. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Branch, Legislative Services (2018-12-13). "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Copyright Act". laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (2017-12-14). "Parliament to undertake review of the Copyright Act". gcnws. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- "INDU - Statutory Review of the Copyright Act". www.ourcommons.ca. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- "Committee Report No. 16 - INDU (42-1) - House of Commons of Canada".

- "Committee News Release - April 10, 2018 - CHPC (42-1) - House of Commons of Canada". www.ourcommons.ca. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- "Cuts Like a Knife: Bryan Adams Calls for Stronger Protections Against One-Sided Record Label Contracts". Michael Geist. 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- "Evidence - CHPC (42-1) - No. 118 - House of Commons of Canada". www.ourcommons.ca. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- Government of Canada, Innovation. "A Consultation on Options for Reform to the Copyright Board of Canada". www.ic.gc.ca. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- Government of Canada, Innovation. "Factsheet: Copyright Board Reform". www.ic.gc.ca. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- "LEGISinfo - House Government Bill C-86 (42-1)". www.parl.ca. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- "The USMCA and Copyright Reform: Who is Writing Canada's Copyright Law Anyway?". Michael Geist. 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- Bob Tarantino (June 24, 2015). "The Complexities of Canada's Extension of Copyright Protection for Sound Recordings". Entertainment and Media Law Signal., discussing the impact of Economic Action Plan 2015 Act, No. 1, S.C. 2015, c. 36, Part 3, Div. 5

- "Copyright Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-42)". Justice Laws Website. Government of Canada. 18 March 2021. Related Provisions 2020, c. 1, s. 34. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- "Chapter 18: Intellectual Property" (PDF). ustr.gov. Office of the United States Trade Representative. 2015. pp. 18–36.

- JIJI Staff (2018-12-10). "Japan to extend copyright period on works including novels and paintings to 70 years on Dec. 30". The Japan Times. Jiji Press. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- "Canadian Publisher on the Terms of Copyright". www.michaelgeist.ca. 2018.

- McGregor, Janyce (2020-04-03). "Canada notifies U.S. and Mexico it has ratified revised NAFTA". CBC News. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "How the Canadian Music Biz is Reacting to New Trade Deal with U.S., Mexico". Billboard.

- Dabrusin, Julie, ed. (15 May 2019). "Shifting Paradigms - Report of the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage". Copyright term extension. Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage. Canada.

Recommendation 7: That the Government of Canada pursue its commitment to implement the extension of copyright from 50 to 70 years after the author's death.

- "Canada Introduces USMCA Implementation Bill…Without a General Copyright Term Extension Provision". Michael Geist. 2019-05-30. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- Geist, Michael (2022-04-08). "Chrystia Freeland's Hidden Tax: How Canada Should Implement the Copyright Term Extension Buried in Budget 2022 - Michael Geist". Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- "An Act to implement certain provisions of the budget tabled in Parliament on April 7, 2022 and other measures". Parliament of Canada. 2022-06-23. Retrieved 2022-11-28.

- "PC Number: 2022-1219". Canada.ca. 2022-11-17. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

- Writers' Union of Canada (3 October 2018). "Canada's Writers Welcome Copyright Term Extension Under USMCA" (Press release). Canada: Writers' Union of Canada. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

The extension of the copyright term of protection to 70 years after the death of the author is a significant improvement and strengthening of creators' rights in Canada, and will stimulate the economy.

- Sanchez, Daniel (December 28, 2018). "Bryan Adams Argues Canada's Copyright Extension Would Only Benefit Major Labels, Not Creators". AmpSuite. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Vollmer, Timothy (October 1, 2018). "New NAFTA Would Harm Canadian Copyright Reform and Shrink the Public Domain". Creative Commons. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- "Effects of the Canada, US, Mexico Agreement Term Extensions" (PDF). Canadian Federation of Library Associations. January 1, 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- Vaver 2011.

- Cinar Corporation v. Robinson, 2013 SCC 73 (23 December 2013)

- Jarvis-Tinus 1992.

- Gould Estate v Stoddart Publishing Co Ltd, 1998 CanLII 5513, 39 OR (3d) 545 (6 May 1998), Court of Appeal (Ontario, Canada)

- Netupsky et al. v. Dominion Bridge Co. Ltd., 1971 CanLII 172, [1972] SCR 368 (5 October 1971)

- Delrina Corp. v. Triolet Systems Inc., 2002 CanLII 11389, 58 OR (3d) 339 (1 March 2002), Court of Appeal (Ontario, Canada)

- CCH Canadian Ltd. v. Law Society of Upper Canada, 2004 SCC 13, [2004] 1 SCR 339 (4 March 2004)

- Geist 2010, pp. 90–120.

- Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency v York University 2017 FC 669 (12 July 2017)

- CCLA v York U, par. 255-257

- Copyright Act, ss. 6, 9–12, 23

- Copyright Act, s. 12

- Copyright Act, s. 6.1–6.2

- Copyright Act, s. 9

- Copyright Act, ss. 6.1–6.2

- Copyright Act, s. 14

- Copyright Act, ss. 14.1–14.2, 17.1–17.2

- Copyright Act, s. 7

- Vaver 2000, pp. 104–107; Vaver 2011, pp. 145–147; Wilkinson, Soltau & Deluzio 2015, fn. 58.

- Wilkinson, Soltau & Deluzio 2015, p. 2.

- Wilkinson, Soltau & Deluzio 2015, p. 12.

- Wilkinson, Soltau & Deluzio 2015, pp. 7–9.

- Brown & Campbell 2010, p. 234.

- Copyright Act, s. 2

- Brown & Campbell 2010, p. 235.

- Brown & Campbell 2010, p. 236.

- Geist, Michael (2017-03-03). "Canadian DMCA in Action: Court Awards Massive Damages in First Major Anti-Circumvention Copyright Ruling". Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Legislative Summary of Bill C-11: An Act to amend the Copyright Act". Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- "Caving to Washington? "Canadian DMCA" expected to pass". Ars Technica. 2011-09-30. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- "What is CIPO". Canadian Intellectual Property Office. Archived from the original on 2012-04-10. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- "Our Mandate". Copyright Board. January 2001.

- Vaver 2000, pp. 216–221.

- "Tariff of Levies to Be Collected by CPCC on the Sale, in Canada, of Blank Audio Recording Media". Canada Gazette. 31 August 2013.

- "Statement of Royalties to Be Collected by Access Copyright for the Reprographic Reproduction, in Canada, of Works in its Repertoire" (PDF). Canada Gazette. June 27, 2009.

- Geist 2010, pp. 503–540.

- Alberta (Education) v. Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), 2012 SCC 37, [2012] 2 SCR 345 (12 July 2012)

- "Statement of Royalties to Be Collected by Access Copyright for the Reprographic Reproduction, in Canada, of Works in its Repertoire" (PDF). Canada Gazette. January 19, 2013.

- "Tariffs proposed by Access Copyright". Copyright Board. January 2001.

Bibliography

- Bannerman, Sara (2013). The Struggle for Canadian Copyright: Imperialism to Internationalism, 1842–1971. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-2406-4.

- Brown, D. Jeffrey; Campbell, Marisia (2010). "Copyright". In McCormack, Stuart C. (ed.). Intellectual Property Law of Canada (2nd ed.). Huntington, New York: Juris Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57823-264-2.

- Dawson, S. E. (1882). Copyright in Books: An Inquiry into its Origin, and an Account of the Present State of the Law in Canada. Montreal: Dawson Brothers. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Erola, Judy; Fox, Francis (1984). From Gutenberg to Telidon: A White Paper on Copyright. Ottawa: Consumer and Corporate Affairs Canada.

- Geist, Michael (2010). From "Radical Extremism" to "Balanced Copyright": Canadian Copyright and the Digital Agenda. Toronto: Irwin Law. ISBN 978-1-55221-204-2.

- Jarvis-Tinus, Jill (1992). "Legal Issues Regarding Oral Histories". Oral History Forum. Canadian Oral History Association. 12: 18–24. ISSN 1923-0567. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- Keyes, A. A.; Brunet, C. (1977). Copyright in Canada: Proposals for Revision of the Law. Ottawa: Consumer and Corporate Affairs Canada.

- Moyse, Pierre-Emmanuel (2008). "Canadian Colonial Copyright: The Colony Strikes Back". In Moyse, Ysolde (ed.). An Emerging Intellectual Property Paradigm: Perspectives from Canada. Queen Mary Studies in Intellectual Property. Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84720-597-1.

- Vaver, David (2000). Copyright Law. Toronto: Irwin Law. ISBN 978-1-55221-034-5.

- ——— (2011). Intellectual Property Law: Copyright, Patents, Trade-Marks (2nd ed.). Toronto: Irwin Law. ISBN 978-1-55221-209-7.

- Wilkinson, Margaret Ann; Soltau, Carolyn; Deluzio, Tierney G. B. (2015). "Copyright in Photographs in Canada since 2012" (PDF). Open Shelf. Ontario Library Association. ISSN 2368-1837. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

Further reading

- Bannerman, Sara (2013). The Struggle for Canadian Copyright: Imperialism to Internationalism, 1842-1971. University of British Columbia. OCLC 1058459616.

- Fox, Harold G. (1944). The Canadian Law of Copyright. University of Toronto Press. OCLC 3265423.

- Mignault, Pierre-Basile (1880). "La propriété littéraire". La Thémis (in French). 2 (10): 289–298. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Perrault, Antonio (1924). "La propriété des œuvres intellectuelles". La Revue du droit (in French). 3: 49ff.

- Wilkinson, Margaret Ann; Deluzio, Tierney G. B. (2016). "The Term of Copyright Protection in Photographs". Canadian Intellectual Property Review. Intellectual Property Institute of Canada. 31: 95–109. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.