Writer

A writer is a person who uses written words in different writing styles and techniques to communicate ideas. Writers produce different forms of literary art and creative writing such as novels, short stories, books, poetry, travelogues, plays, screenplays, teleplays, songs, and essays as well as other reports and news articles that may be of interest to the general public. Writers' texts are published across a wide range of media. Skilled writers who are able to use language to express ideas well, often contribute significantly to the cultural content of a society.[1]

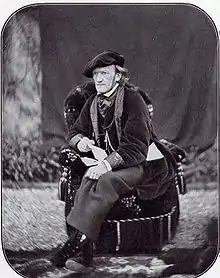

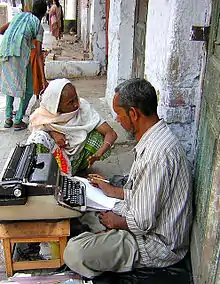

Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, a Spanish writer depicted with the tools of the trade. | |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

Activity sectors | Literature |

| Description | |

| Competencies | Language proficiency, grammar, literacy |

Fields of employment | Mass media, social media |

Related jobs | |

The term "writer" is also used elsewhere in the arts and music, such as songwriter or a screenwriter, but also a stand-alone "writer" typically refers to the creation of written language. Some writers work from an oral tradition.

Writers can produce material across a number of genres, fictional or non-fictional. Other writers use multiple media such as graphics or illustration to enhance the communication of their ideas. Another recent demand has been created by civil and government readers for the work of non-fictional technical writers, whose skills create understandable, interpretive documents of a practical or scientific kind. Some writers may use images (drawing, painting, graphics) or multimedia to augment their writing. In rare instances, creative writers are able to communicate their ideas via music as well as words.[2]

As well as producing their own written works, writers often write about how they write (their writing process);[3] why they write (that is, their motivation);[4] and also comment on the work of other writers (criticism).[5] Writers work professionally or non-professionally, that is, for payment or without payment and may be paid either in advance, or on acceptance, or only after their work is published. Payment is only one of the motivations of writers and many are not paid for their work.

The term writer has been used as a synonym of author, although the latter term has a somewhat broader meaning and is used to convey legal responsibility for a piece of writing, even if its composition is anonymous, unknown or collaborative. Author most often refers to the writer of a book.[6]

Types

Writers choose from a range of literary genres to express their ideas. Most writing can be adapted for use in another medium. For example, a writer's work may be read privately or recited or performed in a play or film. Satire for example, may be written as a poem, an essay, a film, a comic play, or a part of journalism. The writer of a letter may include elements of criticism, biography, or journalism.

Many writers work across genres. The genre sets the parameters but all kinds of creative adaptation have been attempted: novel to film; poem to play; history to musical. Writers may begin their career in one genre and change to another. For example, historian William Dalrymple began in the genre of travel literature and also writes as a journalist. Many writers have produced both fiction and non-fiction works and others write in a genre that crosses the two. For example, writers of historical romances, such as Georgette Heyer, create characters and stories set in historical periods. In this genre, the accuracy of the history and the level of factual detail in the work both tend to be debated. Some writers write both creative fiction and serious analysis, sometimes using other names to separate their work. Dorothy Sayers, for example, wrote crime fiction but was also a playwright, essayist, translator, and critic.

Literary and creative

Poet

I Will Write

He had done for her all that a man could,

And some might say, more than a man should,

Then was ever a flame so recklessly blown out

Or a last goodbye so negligent as this?

‘I will write to you,' she muttered briefly,

Tilting her cheek for a polite kiss;

Then walked away, nor ever turned about. ...

Long letters written and mailed in her own head –

There are no mails in a city of the dead.

Robert Graves[7]

Poets make maximum use of the language to achieve an emotional and sensory effect as well as a cognitive one. To create these effects, they use rhyme and rhythm and they also apply the properties of words with a range of other techniques such as alliteration and assonance. A common topic is love and its vicissitudes. Shakespeare's best-known love story Romeo and Juliet, for example, written in a variety of poetic forms, has been performed in innumerable theaters and made into at least eight cinematic versions.[8] John Donne is another poet renowned for his love poetry.

Novelist

Every novel worthy of the name is like another planet, whether large or small, which has its own laws just as it has its own flora and fauna. Thus, Faulkner's technique is certainly the best one with which to paint Faulkner's world, and Kafka's nightmare has produced its own myths that make it communicable. Benjamin Constant, Stendhal, Eugène Fromentin, Jacques Rivière, Radiguet, all used different techniques, took different liberties, and set themselves different tasks.

François Mauriac, novelist[9]

Satirist

A satirist uses wit to ridicule the shortcomings of society or individuals, with the intent of revealing stupidity. Usually, the subject of the satire is a contemporary issue such as ineffective political decisions or politicians, although human vices such as greed are also a common and prevalent subject. Philosopher Voltaire wrote a satire about optimism called Candide, which was subsequently turned into an opera, and many well known lyricists wrote for it. There are elements of Absurdism in Candide, just as there are in the work of contemporary satirist Barry Humphries, who writes comic satire for his character Dame Edna Everage to perform on stage.

Satirists use different techniques such as irony, sarcasm, and hyperbole to make their point and they choose from the full range of genres – the satire may be in the form of prose or poetry or dialogue in a film, for example. One of the most well-known satirists is Jonathan Swift who wrote the four-volume work Gulliver's Travels and many other satires, including A Modest Proposal and The Battle of the Books.

It is amazing to me that ... our age is almost wholly illiterate and has hardly produced one writer upon any subject.

Jonathan Swift, satirist (1704)[10]

Short story writer

A short story writer is a writer of short stories, works of fiction that can be read in a single sitting.

Librettist

Libretti (the plural of libretto) are the texts for musical works such as operas. The Venetian poet and librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte, for example, wrote the libretto for some of Mozart's greatest operas. Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa were Italian librettists who wrote for Giacomo Puccini. Most opera composers collaborate with a librettist but unusually, Richard Wagner wrote both the music and the libretti for his works himself.

Chi son? Sono poeta. Che cosa faccio? Scrivo. E come vivo? Vivo. ("Who am I? I'm a poet. What do I do? I write. And how do I live? I live.")

Rodolpho, in Puccini's La bohème[11]

Lyricist

Usually writing in verses and choruses, a lyricist specializes in writing lyrics, the words that accompany or underscore a song or opera. Lyricists also write the words for songs. In the case of Tom Lehrer, these were satirical. Lyricist Noël Coward, who wrote musicals and songs such as "Mad Dogs and Englishmen" and the recited song "I Went to a Marvellous Party", also wrote plays and films and performed on stage and screen as well. Writers of lyrics, such as these two, adapt other writers' work as well as create entirely original parts.

Making lyrics feel natural, sit on music in such a way that you don't feel the effort of the author, so that they shine and bubble and rise and fall, is very, very hard to do.

Stephen Sondheim, lyricist[12]

Playwright

A playwright writes plays which may or may not be performed on a stage by actors. A play's narrative is driven by dialogue. Like novelists, playwrights usually explore a theme by showing how people respond to a set of circumstances. As writers, playwrights must make the language and the dialogue succeed in terms of the characters who speak the lines as well as in the play as a whole. Since most plays are performed, rather than read privately, the playwright has to produce a text that works in spoken form and can also hold an audience's attention over the period of the performance. Plays tell "a story the audience should care about", so writers have to cut anything that worked against that.[13] Plays may be written in prose or verse. Shakespeare wrote plays in iambic pentameter as does Mike Bartlett in his play King Charles III (2014).[13]

Playwrights also adapt or re-write other works, such as plays written earlier or literary works originally in another genre. Famous playwrights such as Henrik Ibsen or Anton Chekhov have had their works adapted several times. The plays of early Greek playwrights Sophocles, Euripides, and Aeschylus are still performed. Adaptations of a playwright's work may be honest to the original or creatively interpreted. If the writers' purpose in re-writing the play is to make a film, they will have to prepare a screenplay. Shakespeare's plays, for example, while still regularly performed in the original form, are often adapted and abridged, especially for the cinema. An example of a creative modern adaptation of a play that nonetheless used the original writer's words, is Baz Luhrmann's version of Romeo and Juliet. The amendment of the name to Romeo + Juliet indicates to the audience that the version will be different from the original. Tom Stoppard's play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead is a play inspired by Shakespeare's Hamlet that takes two of Shakespeare's most minor characters and creates a new play in which they are the protagonists.

Player: It's what the actors do best. They have to exploit whatever talent is given to them, and their talent is dying. They can die heroically, comically, ironically, slowly, suddenly, disgustingly, charmingly or from a great height.

Tom Stoppard, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (Act Two)[14]

Screenwriter

Screenwriters write a screenplay – or script – that provides the words for media productions such as films, television series and video games. Screenwriters may start their careers by writing the screenplay speculatively; that is, they write a script with no advance payment, solicitation or contract. On the other hand, they may be employed or commissioned to adapt the work of a playwright or novelist or other writer. Self-employed writers who are paid by contract to write are known as freelancers and screenwriters often work under this type of arrangement.

Screenwriters, playwrights and other writers are inspired by the classic themes and often use similar and familiar plot devices to explore them. For example, in Shakespeare's Hamlet is a "play within a play", which the hero uses to demonstrate the king's guilt. Hamlet hives the co-operation of the actors to set up the play as a thing "wherein I'll catch the conscience of the king".[15] Teleplay writer Joe Menosky deploys the same "play within a play" device in an episode of the science fiction television series Star Trek: Voyager. The bronze-age playwright/hero enlists the support of a Star Trek crew member to create a play that will convince the ruler (or "patron" as he is called), of the futility of war.[16]

Speechwriter

A speechwriter prepares the text for a speech to be given before a group or crowd on a specific occasion and for a specific purpose. They are often intended to be persuasive or inspiring, such as the speeches given by skilled orators like Cicero; charismatic or influential political leaders like Nelson Mandela; or for use in a court of law or parliament. The writer of the speech may be the person intended to deliver it, or it might be prepared by a person hired for the task on behalf of someone else. Such is the case when speechwriters are employed by many senior-level elected officials and executives in both government and private sectors.

Biographer

Biographers write an account of another person's life. Richard Ellmann (1918–1987), for example, was an eminent and award-winning biographer whose work focused on the Irish writers James Joyce, William Butler Yeats, and Oscar Wilde. For the Wilde biography, he won the 1989 Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

Critic

Critics consider and assess the extent to which a work succeeds in its purpose. The work under consideration may be literary, theatrical, musical, artistic, or architectural. In assessing the success of a work, the critic takes account of why it was done – for example, why a text was written, for whom, in what style, and under what circumstances. After making such an assessment, critics write and publish their evaluation, adding the value of their scholarship and thinking to substantiate any opinion. The theory of criticism is an area of study in itself: a good critic understands and is able to incorporate the theory behind the work they are evaluating into their assessment.[17] Some critics are already writers in another genre. For example, they might be novelists or essayists. Influential and respected writer/critics include the art critic Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) and the literary critic James Wood (born 1965), both of whom have books published containing collections of their criticism. Some critics are poor writers and produce only superficial or unsubstantiated work. Hence, while anyone can be an uninformed critic, the notable characteristics of a good critic are understanding, insight, and an ability to write well.

We can claim with at least as much accuracy as a well-known writer claims of his little books, that no newspaper would dare print what we have to say. Are we going to be very cruel and abusive, then? By no means: on the contrary, we are going to be impartial. We have no friends – that is a great thing – and no enemies.

Charles Baudelaire, introducing his Review of the Paris Salon of 1845[18]

Editor

.jpg.webp)

An editor prepares literary material for publication. The material may be the editor's own original work but more commonly, an editor works with the material of one or more other people. There are different types of editor. Copy editors format text to a particular style and/or correct errors in grammar and spelling without changing the text substantively. On the other hand, an editor may suggest or undertake significant changes to a text to improve its readability, sense or structure. This latter type of editor can go so far as to excise some parts of the text, add new parts, or restructure the whole. The work of editors of ancient texts or manuscripts or collections of works results in differing editions. For example, there are many editions of Shakespeare's plays by notable editors who also contribute original introductions to the resulting publication.[19] Editors who work on journals and newspapers have varying levels of responsibility for the text. They may write original material, in particular editorials, select what is to be included from a range of items on offer, format the material, and/or fact check its accuracy.

Encyclopaedist

Encyclopaedists create organised bodies of knowledge. Denis Diderot (1713–1784) is renowned for his contributions to the Encyclopédie. The encyclopaedist Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590) was a Franciscan whose Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España is a vast encyclopedia of Mesoamerican civilization, commonly referred to as the Florentine Codex, after the Italian manuscript library which holds the best-preserved copy.

Essayist

Essayists write essays, which are original pieces of writing of moderate length in which the author makes a case in support of an opinion. They are usually in prose, but some writers have used poetry to present their argument.

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it.[20] The purpose of a historian is to employ historical analysis to create coherent narratives that explain "what happened" and "why or how it happened". Professional historians typically work in colleges and universities, archival centers, government agencies, museums, and as freelance writers and consultants.[21] Edward Gibbon's six-volume History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire influenced the development of historiography.

Lexicographer

Writers who create dictionaries are called lexicographers. One of the most famous is Samuel Johnson (1709–1784), whose Dictionary of the English Language was regarded not only as a great personal scholarly achievement but was also a dictionary of such pre-eminence, that would have been referred to by such writers as Jane Austen.

Researcher/Scholar

Researchers and scholars who write about their discoveries and ideas sometimes have profound effects on society. Scientists and philosophers are good examples because their new ideas can revolutionise the way people think and how they behave. Three of the best known examples of such a revolutionary effect are Nicolaus Copernicus, who wrote De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543); Charles Darwin, who wrote On the Origin of Species (1859); and Sigmund Freud, who wrote The Interpretation of Dreams (1899).

These three highly influential, and initially very controversial, works changed the way people understood their place in the world. Copernicus's heliocentric view of the cosmos displaced humans from their previously accepted place at the center of the universe; Darwin's evolutionary theory placed humans firmly within, as opposed to above, the order of manner; and Freud's ideas about the power of the unconscious mind overcame the belief that humans were consciously in control of all their own actions.[22]

Translator

Translators have the task of finding some equivalence in another language to a writer's meaning, intention and style. Translators whose work has had very significant cultural effect include Al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yūsuf ibn Maṭar, who translated Elements from Greek into Arabic and Jean-François Champollion, who deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs with the result that he could publish the first translation of the Rosetta Stone hieroglyphs in 1822. Difficulties with translation are exacerbated when words or phrases incorporate rhymes, rhythms, or puns; or when they have connotations in one language that are non-existent in another. For example, the title of Le Grand Meaulnes by Alain-Fournier is supposedly untranslatable because "no English adjective will convey all the shades of meaning that can be read into the simple [French] word 'grand' which takes on overtones as the story progresses."[23] Translators have also become a part of events where political figures who speak different languages meet to look into the relations between countries or solve political conflicts. It is highly critical for the translator to deliver the right information as a drastic impact could be caused if any error occurred.

Even if translation is impossible – we have no choice but to do it: to take the next step and start translating. ... The translator's task is to make us either forget or else enjoy the difference.

Robert Dessaix, translator, author[24]

Blogger

Writers of blogs, which have appeared on the World Wide Web since the 1990s, need no authorisation to be published. The contents of these short opinion pieces or "posts" form a commentary on issues of specific interest to readers who can use the same technology to interact with the author, with an immediacy hitherto impossible. The ability to link to other sites means that some blog writers – and their writing – may become suddenly and unpredictably popular. Malala Yousafzai, a young Pakistani education activist, rose to prominence due to her blog for BBC.

A blog writer is using the technology to create a message that is in some ways like a newsletter and in other ways, like a personal letter. "The greatest difference between a blog and a photocopied school newsletter, or an annual family letter photocopied and mailed to a hundred friends, is the potential audience and the increased potential for direct communication between audience members".[25] Thus, as with other forms of letters the writer knows some of the readers, but one of the main differences is that "some of the audience will be random" and "that presumably changes the way we [writers] write."[25] It has been argued that blogs owe a debt to Renaissance essayist Michel de Montaigne, whose Essais ("attempts"), were published in 1580, because Montaigne "wrote as if he were chatting to his readers: just two friends, whiling away an afternoon in conversation".[26]

Columnist

Columnists write regular parts for newspapers and other periodicals, usually containing a lively and entertaining expression of opinion. Some columnists have had collections of their best work published as a collection in a book so that readers can re-read what would otherwise be no longer available. Columns are quite short pieces of writing so columnists often write in other genres as well. An example is the female columnist Elizabeth Farrelly, who besides being a columnist, is also an architecture critic and author of books.

Diarist

Writers who record their experiences, thoughts, or emotions in a sequential form over a period of time in a diary are known as diarists. Their writings can provide valuable insights into historical periods, specific events, or individual personalities. Examples include Samuel Pepys (1633–1703), an English administrator and Member of Parliament, whose detailed private diary provides eyewitness accounts of events during the 17th century, most notably of the Great Fire of London. Anne Frank (1929–1945) was a 13-year-old Dutch girl whose diary from 1942 to 1944 records both her experiences as a persecuted Jew in World War II and an adolescent dealing with intra-family relationships.

Journalist

Journalists write reports about current events after investigating them and gathering information. Some journalists write reports about predictable or scheduled events such as social or political meetings. Others are investigative journalists who need to undertake considerable research and analysis in order to write an explanation or account of something complex that was hitherto unknown or not understood. Often investigative journalists are reporting criminal or corrupt activity which puts them at risk personally and means that what it is likely that attempts may be made to attack or suppress what they write. An example is Bob Woodward, a journalist who investigated and wrote about criminal activities by the US President.

Journalism ... is a public trust, a responsibility, to report the facts with context and completeness, to speak truth to power, to hold the feet of politicians and officials to the fire of exposure, to discomfort the comfortable, to comfort those who suffer.

Geoffrey Barker, journalist.[27]

Memoirist

Writers of memoirs produce accounts from the memories of their own lives, which are considered unusual, important, or scandalous enough to be of interest to general readers. Although meant to be factual, readers are alerted to the likelihood of some inaccuracies or bias towards an idiosyncratic perception by the choice of genre. A memoir, for example, is allowed to have a much more selective set of experiences than an autobiography which is expected to be more complete and make a greater attempt at balance. Well-known memoirists include Frances Vane, Viscountess Vane, and Giacomo Casanova.

Ghostwriter

Ghostwriters write for, or in the style of, someone else so the credit goes to the person on whose behalf the writing is done.

Letter writer

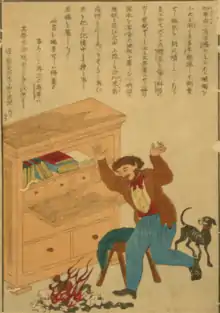

.jpg.webp)

(Photograph by Kusakabe Kimbei)

Writers of letters use a reliable form of transmission of messages between individuals, and surviving sets of letters provide insight into the motivations, cultural contexts, and events in the lives of their writers. Peter Abelard (1079–1142), philosopher, logician, and theologian is known not only for the heresy contained in some of his work, and the punishment of having to burn his own book, but also for the letters he wrote to Héloïse d'Argenteuil (1090?–1164).[28]

The letters (or epistles) of Paul the Apostle were so influential that over the two thousand years of Christian history, Paul became "second only to Jesus in influence and the amount of discussion and interpretation generated".[29][30]

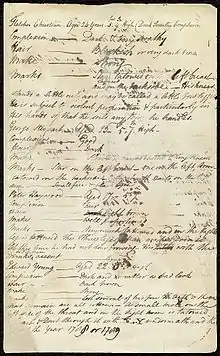

Report writer

Report writers are people who gather information, organise and document it so that it can be presented to some person or authority in a position to use it as the basis of a decision. Well-written reports influence policies as well as decisions. For example, Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) wrote reports that were intended to effect administrative reform in matters concerning health in the army. She documented her experience in the Crimean War and showed her determination to see improvements: "...after six months of incredible industry she had put together and written with her own hand her Notes affecting the Health, Efficiency and Hospital Administration of the British Army. This extraordinary composition, filling more than eight hundred closely printed pages, laying down vast principles of far-reaching reform, discussing the minutest detail of a multitude of controversial subjects, containing an enormous mass of information of the most varied kinds – military, statistical, sanitary, architectural" became for a long time, the "leading authority on the medical administration of armies".[31][32]

The logs and reports of Master mariner William Bligh contributed to his being honourably acquitted at the court-martial inquiring into the loss of HMS Bounty.

Scribe

A scribe writes ideas and information on behalf of another, sometimes copying from another document, sometimes from oral instruction on behalf of an illiterate person, sometimes transcribing from another medium such as a tape recording, shorthand, or personal notes.

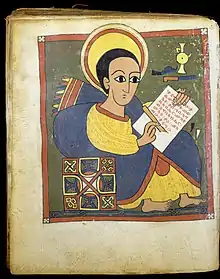

Being able to write was a rare achievement for over 500 years in Western Europe so monks who copied texts were scribes responsible for saving many texts from first times. The monasteries, where monks who knew how to read and write lived, provided an environment stable enough for writing. Irish monks, for example, came to Europe in about 600 and "found manuscripts in places like Tours and Toulouse" which they copied.[33] The monastic writers also illustrated their books with highly skilled art work using gold and rare colors.

Technical writer

A technical writer prepares instructions or manuals, such as user guides or owner's manuals for users of equipment to follow. Technical writers also write different procedures for business, professional or domestic use. Since the purpose of technical writing is practical rather than creative, its most important quality is clarity. The technical writer, unlike the creative writer, is required to adhere to the relevant style guide.

Process and methods

Writing process

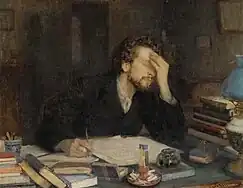

There is a range of approaches that writers take to the task of writing. Each writer needs to find their own process and most describe it as more or less a struggle.[34] Sometimes writers have had the bad fortune to lose their work and have had to start again. Before the invention of photocopiers and electronic text storage, a writer's work had to be stored on paper, which meant it was very susceptible to fire in particular. (In very earlier times, writers used vellum and clay which were more robust materials.) Writers whose work was destroyed before completion include L. L. Zamenhof, the inventor of Esperanto, whose years of work were thrown into the fire by his father because he was afraid that "his son would be thought a spy working code".[35] Essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle, lost the only copy of a manuscript for The French Revolution: A History when it was mistakenly thrown into the fire by a maid. He wrote it again from the beginning.[36] Writers usually develop a personal schedule. Angus Wilson, for example, wrote for a number of hours every morning.[37]

Writer's block is a relatively common experience among writers, especially professional writers, when for a period of time the writer feels unable to write for reasons other than lack of skill or commitment.

Happy are they who don't doubt themselves and whose pens fly across the page

Gustave Flaubert writing to Louise Colet[38]

Sole

Most writers write alone – typically they are engaged in a solitary activity that requires them to struggle with both the concepts they are trying to express and the best way to express it. This may mean choosing the best genre or genres as well as choosing the best words. Writers often develop idiosyncratic solutions to the problem of finding the right words to put on a blank page or screen. "Didn't Somerset Maugham also write facing a blank wall? ... Goethe couldn't write a line if there was another person anywhere in the same house, or so he said at some point."[39]

Collaborative

Collaborative writing means that other authors write and contribute to a part of writing. In this approach, it is highly likely the writers will collaborate on editing the part too. The more usual process is that the editing is done by an independent editor after the writer submits a draft version.

In some cases, such as that between a librettist and composer, a writer will collaborate with another artist on a creative work. One of the best known of these types of collaborations is that between Gilbert and Sullivan. Librettist W. S. Gilbert wrote the words for the comic operas created by the partnership.

Committee

Occasionally, a writing task is given to a committee of writers. The most well-known example is the task of translating the Bible into English, sponsored by King James VI of England in 1604 and accomplished by six committees, some in Cambridge and some in Oxford, who were allocated different sections of the text. The resulting Authorized King James Version, published in 1611, has been described as an "everlasting miracle" because its writers (that is, its Translators) sought to "hold themselves consciously poised between the claims of accessibility and beauty, plainness and richness, simplicity and majesty, the people and the king", with the result that the language communicates itself "in a way which is quite unaffected, neither literary nor academic, not historical, nor reconstructionist, but transmitting a nearly incredible immediacy from one end of human civilisation to another."[40]

Multimedia

Some writers support the verbal part of their work with images or graphics that are an integral part of the way their ideas are communicated. William Blake is one of rare poets who created his own paintings and drawings as integral parts of works such as his Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Cartoonists are writers whose work depends heavily on hand drawn imagery. Other writers, especially writers for children, incorporate painting or drawing in more or less sophisticated ways. Shaun Tan, for example, is a writer who uses imagery extensively, sometimes combining fact, fiction and illustration, sometimes for a didactic purpose, sometimes on commission.[41] Children's writers Beatrix Potter, May Gibbs, and Theodor Seuss Geisel are as well known for their illustrations as for their texts.

Crowd sourced

Some writers contribute very small sections to a part of writing that cumulates as a result. This method is particularly suited to very large works, such as dictionaries and encyclopaedias. The best known example of the former is the Oxford English Dictionary, under the editorship of lexicographer James Murray, who was provided with the prolific and helpful contributions of W.C. Minor, at the time an inmate of a hospital for the criminally insane.[42]

The best known example of the latter – an encyclopaedia that is crowdsourced – is Wikipedia, which relies on millions of writers and editors such as Simon Pulsifer[43] worldwide.

Motivations

Writers have many different reasons for writing, among which is usually some combination of self-expression[44] and recording facts, history or research results. The many physician writers, for example, have combined their observation and knowledge of the human condition with their desire to write and contributed many poems, plays, translations, essays and other texts. Some writers write extensively on their motivation and on the likely motivations of other writers. For example, George Orwell's essay "Why I Write" (1946) takes this as its subject. As to "what constitutes success or failure to a writer", it has been described as "a complicated business, where the material rubs up against the spiritual, and psychology plays a big part".[45]

The moral I draw is that the writer should seek his reward in the pleasure of his work and in release from the burden of this thoughts; and, indifferent to aught else, care nothing for praise or censure, failure or success.

W. Somerset Maugham in The Moon and Sixpence (1919)[46]

Command

Some writers are the authors of specific military orders whose clarity will determine the outcome of a battle. Among the most controversial and unsuccessful was Lord Raglan's order at the Charge of the Light Brigade, which being vague and misinterpreted, led to defeat with many casualties.

Develop skill/explore ideas

Some writers use the writing task to develop their own skill (in writing itself or in another area of knowledge) or explore an idea while they are producing a piece of writing. Philologist J. R. R. Tolkien, for example, created a new language for his fantasy books.

For me the private act of poetry writing is songwriting, confessional, diary-keeping, speculation, problem-solving, storytelling, therapy, anger management, craftsmanship, relaxation, concentration and spiritual adventure all in one inexpensive package.

Stephen Fry, author, poet, playwright, screenwriter, journalist[47]

Entertain

Some genres are a particularly appropriate choice for writers whose chief purpose is to entertain. Among them are limericks, many comics and thrillers. Writers of children's literature seek to entertain children but are also usually mindful of the educative function of their work as well.

I think that I shall never see

a billboard lovely as a tree;

Indeed, unless the billboards fall

I'll never see a tree at all.

Ogden Nash, humorous poet, reworking a poem by Joyce Kilmer for comic effect.[48]

Influence

Anger has motivated many writers, including Martin Luther, angry at religious corruption, who wrote the Ninety-five Theses in 1517, to reform the church, and Émile Zola (1840–1902) who wrote the public letter, J'Accuse in 1898 to bring public attention to government injustice, as a consequence of which he had to flee to England from his native France. Such writers have affected ideas, opinion or policy significantly.

Payment

Even though he is in love with the same woman, Cyrano helps his inarticulate friend, Rageneau, to woo her by writing on his behalf ...

CYRANO: What hour is it now, Ragueneau?

RAGUENEAU (stopping short in the act of thrusting to look at the clock): Five minutes after six!...'I touch!' (He straightens himself): ...Oh! to write a ballade!

...

RAGUENEAU: Ten minutes after six.

CYRANO: (nervously seating himself at Ragueneau's table, and drawing some paper toward him): A pen!. . .

RAGUENEAU (giving him the one from behind his ear): Here – a swan's quill.

...

CYRANO (taking up the pen, and motioning Ragueneau away): Hush! (To himself): I will write, fold it, give it her, and fly! (Throws down the pen): Coward! ...But strike me dead if I dare to speak to her, ...ay, even one single word! (To Ragueneau): What time is it?

RAGUENEAU: A quarter after six! ...

CYRANO (striking his breast): Ay-a single word of all those here! here! But writing, 'tis easier done... (He takes up the pen): Go to, I will write it, that love-letter! Oh! I have writ it and rewrit it in my own mind so oft that it lies there ready for pen and ink; and if I lay but my soul by my letter-sheet, 'tis naught to do but to copy from it. (He writes. ...)

Edmond Rostand, Cyrano de Bergerac

Act II, Scene 2, (3)[49]

Writers may write a particular piece for payment (even if at other times, they write for another reason), such as when they are commissioned to create a new work, transcribe an original one, translate another writer's work, or write for someone who is illiterate or inarticulate. In some cases, writing has been the only way an individual could earn an income. Frances Trollope is an example of women who wrote to save herself and her family from penury, at a time when there were very few socially acceptable employment opportunities for them. Her book about her experiences in the United States, called Domestic Manners of the Americans became a great success, "even though she was over fifty and had never written before in her life" after which "she continued to write hard, carrying this on almost entirely before breakfast".[50] According to her writer son Anthony Trollope "her books saved the family from ruin".[50]

I write for two reasons; partly to make money and partly to win the respect of people whom I respect.

E. M. Forster, novelist, essayist, librettist[51]

Teach

Aristotle, who was tutor to Alexander the Great, wrote to support his teaching. He wrote two treatises for the young prince: "On Monarchy", and "On Colonies"[52] and his dialogues also appear to have been written either "as lecture notes or discussion papers for use in his philosophy school at the Athens Lyceum between 334 and 323 BC."[52] They encompass both his 'scientific' writings (metaphysics, physics, biology, meteorology, and astronomy, as well as logic and argument) the 'non-scientific' works (poetry, oratory, ethics, and politics), and "major elements in traditional Greek and Roman education".[52]

Writers of textbooks also use writing to teach and there are numerous instructional guides to writing itself. For example, many people will find it necessary to make a speech "in the service of your company, church, civic club, political party, or other organization" and so, instructional writers have produced texts and guides for speechmaking.[53]

Tell a story

Many writers use their skill to tell the story of their people, community or cultural tradition, especially one with a personal significance. Examples include Shmuel Yosef Agnon; Miguel Ángel Asturias; Doris Lessing; Toni Morrison; Isaac Bashevis Singer; and Patrick White. Writers such as Mario Vargas Llosa, Herta Müller, and Erich Maria Remarque write about the effect of conflict, dispossession and war.

Seek a lover

Writers use prose, poetry, and letters as part of courtship rituals. Edmond Rostand's play Cyrano de Bergerac, written in verse, is about both the power of love and the power of the self-doubting writer/hero's writing talent.

Authorship

%252C_comme_%C3%A9crivain_du_couvent_de_B%C3%A9ja.jpg.webp)

Pen names

Writers sometimes use a pseudonym, otherwise known as a pen name or "nom de plume". The reasons they do this include to separate their writing from other work (or other types of writing) for which they are known; to enhance the possibility of publication by reducing prejudice (such as against women writers or writers of a particular race); to reduce personal risk (such as political risks from individuals, groups or states that disagree with them); or to make their name better suit another language.

Examples of well-known writers who used a pen name include: George Eliot (1819–1880), whose real name was Mary Anne (or Marian) Evans; George Orwell (1903–1950), whose real name was Eric Blair; George Sand (1804–1876), whose real name was Lucile Aurore Dupin; Dr. Seuss (1904–1991), whose real name was Theodor Seuss Geisel; Stendhal (1783–1842), whose real name was Marie-Henri Beyle; and Mark Twain (1835–1910), whose real name was Samuel Langhorne Clemens.

Apart from the large numbers of works attributable only to "Anonymous", there are a large number of writers who were once known and are now unknown. Efforts are made to find and re-publish these writers' works. One example is the publication of books like Japan As Seen and Described by Famous Writers (a 2010 reproduction of a pre-1923 publication) by "Anonymous".[54] Another example is the founding of a Library and Study Centre for the Study of Early English Women's Writing in Chawton, England.[55]

Fictional writers

Some fictional writers are very well known because of the strength of their characterization by the real writer or the significance of their role as writer in the plot of a work. Examples of this type of fictional writer include Edward Casaubon, a fictional scholar in George Eliot's Middlemarch, and Edwin Reardon, a fictional writer in George Gissing's New Grub Street. Casaubon's efforts to complete an authoritative study affect the decisions taken by the protagonists in Eliot's novel and inspire significant parts of the plot. In Gissing's work, Reardon's efforts to produce high quality writing put him in conflict with another character, who takes a more commercial approach. Robinson Crusoe is a fictional writer who was originally credited by the real writer (Daniel Defoe) as being the author of the confessional letters in the work of the same name. Bridget Jones is a comparable fictional diarist created by writer Helen Fielding. Both works became well-known and popular; their protagonists and story were developed further through many adaptations, including film versions. Cyrano de Bergerac was a real writer who created a fictional character with his own name. The Sibylline Books, a collection of prophecies were supposed to have been purchased from the Cumaean Sibyl by the last king of Rome. Since they were consulted during periods of crisis, it could be said that they are a case of real works created by a fictional writer.

Writers of sacred texts

Religious texts or scriptures are the texts which different religious traditions consider to be sacred, or of central importance to their religious tradition. Some religions and spiritual movements believe that their sacred texts are divinely or supernaturally revealed or inspired, while others have individual authors.

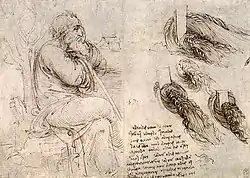

Controversial writing

Skilled writers influence ideas and society, so there are many instances where a writer's work or opinion has been unwelcome and controversial. In some cases, they have been persecuted or punished. Aware that their writing will cause controversy or put themselves and others into danger, some writers self-censor; or withhold their work from publication; or hide their manuscripts; or use some other technique to preserve and protect their work. Two of the most famous examples are Leonardo da Vinci and Charles Darwin. Leonardo "had the habit of conversing with himself in his writings and of putting his thoughts into the clearest and most simple form". He used "left-handed or mirror writing" (a technique described as "so characteristic of him") to protect his scientific research from other readers.[56] The fear of persecution, social disgrace, and being proved incorrect are regarded as contributing factors to Darwin's delaying the publication of his radical and influential work On the Origin of Species.

One of the results of controversies caused by a writer's work is scandal, which is a negative public reaction that causes damage to reputation and depends on public outrage. It has been said that it is possible to scandalise the public because the public "wants to be shocked in order to confirm its own sense of virtue".[57] The scandal may be caused by what the writer wrote or by the style in which it was written. In either case, the content or the style is likely to have broken with tradition or expectation. Making such a departure may in fact, be part of the writer's intention or at least, part of the result of introducing innovations into the genre in which they are working. For example, novelist D H Lawrence challenged ideas of what was acceptable as well as what was expected in form. These may be regarded as literary scandals, just as, in a different way, are the scandals involving writers who mislead the public about their identity, such as Norma Khouri or Helen Darville who, in deceiving the public, are considered to have committed fraud.

Writers may also cause the more usual type of scandal – whereby the public is outraged by the opinions, behaviour or life of the individual (an experience not limited to writers). Poet Paul Verlaine outraged society with his behaviour and treatment of his wife and child as well as his lover. Among the many writers whose writing or life was affected by scandals are Oscar Wilde, Lord Byron, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and H. G. Wells. One of the most famously scandalous writers was the Marquis de Sade who offended the public both by his writings and by his behaviour.

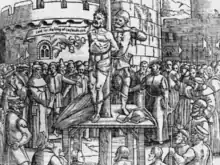

Punishment

The consequence of scandal for a writer may be censorship or discrediting of the work, or social ostracism of its creator. In some instances, punishment, persecution, or prison follow. The list of journalists killed in Europe, list of journalists killed in the United States and the list of journalists killed in Russia are examples. Others include:

- The Balibo Five, a group of Australian television journalists who were killed while attempting to report on Indonesian incursions into Portuguese Timor in 1975.

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945), an influential theologian who wrote The Cost of Discipleship and was hanged for his resistance to Nazism.

- Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), who was sentenced to imprisonment for heresy as a consequence of writing in support of the then controversial theory of heliocentrism, although the sentence was almost immediately commuted to house arrest.

- Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937), who wrote political theory and criticism and was imprisoned for this by the Italian Fascist regime.

- Günter Grass (1927–2015), whose poem "What Must Be Said" led to his being declared persona non grata in Israel.

- Peter Greste (born 1965), a journalist who was imprisoned in Egypt for news reporting which was "damaging to national security."[58]

- Primo Levi (1919–1987) who, among many Jews imprisoned during World War II, wrote an account of his incarceration called If This Is a Man.

- Sima Qian (145 or 135 BC – 86 BC) who "successfully defended a vilified master from defamatory charges" and was given "the choice between castration or execution." He "became a eunuch and had to bury his own book ... in order to protect it from the authorities."[59]

- Salman Rushdie (born 1947), whose novel The Satanic Verses was banned and burned internationally after causing such a worldwide storm that a fatwā was issued against him. Though Rushdie survived, numerous others were killed in incidents connected to the novel.

- Roberto Saviano (born 1979), whose best-selling book Gomorrah provoked the Neapolitan Camorra, annoyed Silvio Berlusconi and led to him receiving permanent police protection.

- Simon Sheppard (born 1957) who was imprisoned in the UK for inciting racial hatred.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008), who used his experience of imprisonment as the subject of his writing in One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and Cancer Ward—the latter, while legally published in the Soviet Union, had to gain the approval of the USSR Union of Writers.

- William Tyndale (c. 1494 – 1536), who was executed because he translated the Bible into English.

Protection and representation

The organisation Reporters Without Borders (also known by its French name: Reporters Sans Frontières) was set up to help protect writers and advocate on their behalf.

The professional and industrial interests of writers are represented by various national or regional guilds or unions. Examples include writers guilds in Australia and Great Britain and unions in Arabia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Canada, Estonia, Hungary, Ireland, Moldova, Philippines, Poland, Quebec, Romania, Russia, Sudan, and Ukraine. In the United States, there is both a writers guild and a National Writers Union.

Awards

There are many awards for writers whose writing has been adjudged excellent. Among them are the many literary awards given by individual countries, such as the Prix Goncourt and the Pulitzer Prize, as well as international awards such as the Nobel Prize in Literature. Russian writer Boris Pasternak (1890–1960), under pressure from his government, reluctantly declined the Nobel Prize that he won in 1958.

See also

References

- Magill, Frank N. (1974). Cyclopedia of World Authors. Vol. I, II, III (revised ed.). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Salem Press. pp. 1–1973. [A compilation of the bibliographies and short biographies of notable authors up to 1974.]

- Nobel prize winner Rabindranath Tagore is an example.

- Nicolson, Adam (2011). When God Spoke English: The Making of the King James Bible. London: Harper Press. ISBN 978-0-00-743100-7.

- See, for example, Will Blythe, ed. (c. 1998). Why I write: thoughts on the practice of fiction. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0316102296.

- Jonathan Franzen, for example, criticised John Updike for being "exquisitely preoccupied with his own literary digestive processes ..." and his "lack of interest in the bigger postwar, postmodern, socio-technological picture" Franzen, Jonathan (6 September 2013). "Franzen on Kraus: Footnote 89". The Paris Review (206). Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- "Definition of AUTHOR". www.merriam-webster.com. 12 October 2023.

- Graves, Robert (1957). Poems Selected by Himself. Penguin Books. p. 204.

- 1936, 1954, 1955, 1966, 1968, 1978, 2013, 2014. IMDb listing.

- Le Marchand, Jean (Summer 1953). "Interviews: François Mauriac, The Art of Fiction No. 2". The Paris Review (2). Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- The Epistle Dedicatory of A Tale of a Tub. For text at Wikisource, see A Tale of a Tub

- Excerpt of Rodolpho's aria in Act I of La bohème

- Lipton, James (Spring 1997). "Interview: Stephen Sondheim, The Art of the Musical". The Paris Review. Spring 1997 (142). Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- Bartlett, Mike (18 November 2015). "Mike Bartlett on writing King Charles III". Sydney Theatre Company Magazine. Sydney Theatre Company. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- Stopppard, Tom (1967). Rosencrantz and Guildentern Are Dead. Faber and Faber. p. 75. ISBN 0-571-08182-7.

- The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark/Act 2, (Act II, Sc.2, line 609)

- See Season 6, Episode 22: "Muse", (Star Trek: Voyager)

- For example, see Habib, M.A.R. (2005). A History of Literary Criticism and Theory. MA, USA; Oxford, UK; Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-23200-1.

- Baudelaire, Charles (1965). "The Salon of 1845". In Mayne, Jonathan (ed.). Baudelaire – Art in Paris 1845–1862: Reviews of Salons and other exhibitions. Translated by Mayne, Jonathan. London: Phaidon Press. p. 1.

- Warner, Beverley Ellison (2012). Famous Introductions to Shakespeare's Plays by the Notable Editors of the Eighteenth Century (1906). HardPress. ISBN 978-1290807081.

- "Historian". Wordnetweb.princeton.edu. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Anthony Grafton and Robert B. Townsend, "The Parlous Paths of the Profession" Perspectives on History (Sept. 2008) online

- Weinert, Friedel (2009). Copernicus, Darwin and Freud: Revolutions in the History and Philosophy of Science. Malden, Massachusetts, USA; Oxford UK: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-8184-6.

- Gopnik, Adam (2007). "Introduction" to the English translation of "Le Grand Meaulnes". London: Penguin Books. p. vii–viii. ISBN 9780141441894.

- Dessaix, Robert (1998). "Dandenongs Gothic: On Translation" in (and so forth). Sydney: Pan MacMillan Australia Ltd. p. 307. ISBN 0-7329-0943-0.

- Rettberg, Jill Walker (2008). Blogging. Cambridge UK; Malden, Massachusetts USA: Polity Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-7456-4133-1.

- Bakewell, Sarah (12 November 2010). "What Bloggers Owe Montaigne". The Paris Review. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- Barker and de Brito, controversially lamenting the preference for looks over experience in televised journalism. Geoffrey Barker (2 May 2013). "Switch off the TV babes for some real news". The Age. Retrieved 3 May 2013. Sam de Brito (2 May 2013). "Reality's bite worse than Barker". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- For text see Letters of Abélard and Héloïse

- Steven R. Cartwright, ed. (2013). A Companion to St. Paul in the Middle Ages. Leiden The Netherlands: Koninklijke, Brill, NV. p. 1. ISBN 978-90-04-23672-1.

- William S. Babcock, ed. (1990). Paul and the Legacies of Paul. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press.

- Strachey, Lytton (1918). "Florence Nightingale – 3". Eminent Victorians (1981 ed.). Penguin Modern Classics. pp. 142–3. ISBN 0-14-000649-4.

- Nightingale, Florence. Notes on matters affecting the health, efficiency, and hospital administration of the British army : founded chiefly on the experience of the late war. OCLC 7660327.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Clark, Kenneth (1969). Civilisation. London: Penguin Books. pp. 28–29. ISBN 0-14-016589-4.

- Older, Daniel José. "Writing Begins With Forgiveness: Why One of the Most Common Pieces of Writing Advice Is Wrong". Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- Bryson, Bill (1990). Mother Tongue – The English Language. Penguin Books. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-14-014305-8.

- Eliot, Charles William, Ed. "Introductory Note" in The Harvard Classics, Vol. XXV, Part 3. New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1909–14.

- Wilson, Angus (1957). "Interview with Angus Wilson". The Paris Review (Autumn-Winter No.17). Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- Plate caption to an image of a much-corrected page of Madame Bovary in the Bibliothèque Municipale de Rouen. In Brown, Frederick (2006). Flaubert: a biography. New York: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 9780316118781.

- Hughes, Ted (1995). "Ted Hughes: The Art of Poetry No. 71". The Paris Review. Spring (134). Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- Nicolson, Adam (2011). When God Spoke English: The Making of the King James Bible. London: Harper Press. ISBN 978-0-00-743100-7.(p.240, 243)

- Tan, Shaun (2012). The Oopsatoreum. Sydney: Powerhouse Publishing. ISBN 9781863171441.

- Winchester, Simon (1998). The Surgeon of Crowthorne: a tale of murder, madness and the love of words. London: Viking. ISBN 0670878626.

- Grossman, Lev (16 December 2006). "Simon Pulsifer: The Duke of Data". Time. Archived from the original on 10 February 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- Peter Matthiessen, George Plimpton (1954). "William Styron, The Art of Fiction No. 5". The Paris Review (Spring). Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- Sullivan, Jane (27 December 2014). "JK Rowling on turning failure into success". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- Maugham, Somerset (1999). "2". The Moon and Sixpence. Vintage. p. 8. ISBN 9780099284765.

- Fry, Stephen (2007). The Ode Less Travelled – Unlocking the Poet Within. Arrow Books. pp. xii. ISBN 978-0-09-950934-9.

- Nash, Ogden, "Song of the Open Road", The Face Is Familiar (Garden City Publishing, 1941), p. 21

- "Rostand, Cyrano de Bergerac: Act II, Scene 2, (3)".

- Moore, Katherine (1974). Victorian Wives. London, New York: Allison & Busby. pp. 65–71. ISBN 0-85031-634-0.

- Quoted in the introduction to the author in the 1962 edition of E.M. Forster (1927). Aspects of the Novel. Penguin.

- R.G. Tanner (2000). "Aristotle's Works: The Possible Origins of the Alexandria Collection". In Roy MacLeod (ed.). The Library of Alexandria. Cairo, Egypt: The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 79–91. ISBN 977-424-710-8.

- Dowis, Richard (2000). The Lost Art of the Great Speech: How to Write One : How to Deliver It. New York: AMA publications. p. 2. ISBN 0-8144-7054-8.

- Anonymous (2010). Japan As Seen and Described by Famous Writers (published pre-1923). BiblioLife. ISBN 9781142479084.

- "Chawton House Library | Home to early English women's writing".

- "Leonardo's Manuscripts" in Leonardo de Vinci (Authoritative work, published in Italy by Istituto Geografico De Agostini, in conjunction with exhibition of Leonardo's work in Milan in 1938 (re-edited English translation) ed.). New York: Reynal and Company, in association with William Morris and Company. p. 157.

- Wilson, Colin; Damon Wilson (2011). Scandal!: An Explosive Exposé of the Affairs, Corruption and Power Struggles of the Rich and Famous. Random House.

- "Egypt crisis: Al-Jazeera journalists arrested in Cairo". BBC News. 30 December 2013.

- Battles, Matthew (2003). Library – An Unquiet History. London: William Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-00887-7.p40