Corned beef

Corned beef, or salt beef in some Commonwealth countries, is salt-cured brisket of beef.[1] The term comes from the treatment of the meat with large-grained rock salt, also called "corns" of salt. Sometimes, sugar and spices are added to corned beef recipes. Corned beef is featured as an ingredient in many cuisines.

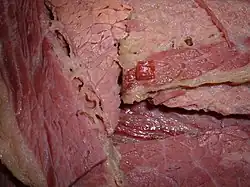

Cooked corned beef | |

| Alternative names | Salt beef, bully beef (if canned) |

|---|---|

| Main ingredients | Beef, salt |

| Variations | Adding sugar and spices |

Most recipes include nitrates, which convert the natural myoglobin in beef to nitrosomyoglobin, giving it a pink color. Nitrates and nitrites reduce the risk of dangerous botulism during curing by inhibiting the growth of Clostridium botulinum bacteria spores,[2] but have been linked to increased cancer risk in mice.[3] Beef cured without nitrates or nitrites has a gray color, and is sometimes called "New England corned beef".[4]

Tinned corned beef, alongside salt pork and hardtack, was a standard ration for many militaries and navies from the 17th through the early 20th centuries, including World War I and World War II, during which fresh meat was rationed.[5] Corned beef remains popular worldwide as an ingredient in a variety of regional dishes and as a common part in modern field rations of various armed forces around the world.

History

Although the exact origin of corned beef is unknown, it most likely came about when people began preserving meat through salt-curing. Evidence of its legacy is apparent in numerous cultures, including ancient Europe and the Middle East.[6] The word corn derives from Old English and is used to describe any small, hard particles or grains.[7] In the case of corned beef, the word may refer to the coarse, granular salts used to cure the beef.[6] The word "corned" may also refer to the corns of potassium nitrate, also known as saltpeter, which were formerly used to preserve the meat.[8][9][10]

19th century Atlantic trade

Although the practice of curing beef was found locally in many cultures, the industrial production of corned beef started in the British Industrial Revolution. Irish corned beef was used and traded extensively from the 17th century to the mid-19th century for British civilian consumption and as provisions for the British naval fleets and North American armies due to its nonperishable nature.[11] The product was also traded to the French, who used it in their colonies in the Caribbean as sustenance for both the colonists and enslaved labourers.[12] The 17th century British industrial processes for corned beef did not distinguish between different cuts of beef beyond the tough and undesirable parts such as the beef necks and shanks.[12][13] Rather, the grading was done by the weight of the cattle into "small beef", "cargo beef" and "best mess beef", the first being the worst and the last the best.[12] Much of the undesirable portions and lower grades were traded to the French, while better parts were saved for consumption in Britain or her colonies.[12]

Ireland produced a significant amount of the corned beef in the Atlantic trade from local cattle and salt imported from the Iberian Peninsula and southwestern France.[12] Coastal cities, such as Dublin, Belfast and Cork, created vast beef curing and packing industries, with Cork producing half of Ireland's annual beef exports in 1668.[13] Although the production and trade of corned beef as a commodity was a source of great wealth for the nations of Europe, in the colonies the product was looked upon with disdain due to its consumption by the poor and slaves.[12]

Increasing corned beef production to satisfy the rising number of people moving to the cities from the countryside during the Industrial Revolution worsened the effects of the Irish Famine of 1740–41 and the Great Irish Famine:

The Celtic grazing lands of ... Ireland had been used to pasture cows for centuries. The British colonized ... the Irish, transforming much of their countryside into an extended grazing land to raise cattle for a hungry consumer market at home ... The British taste for beef had a devastating impact on the impoverished and disenfranchised [the] people of ... Ireland. Pushed off the best pasture land and forced to farm smaller plots of marginal land, the Irish turned to the potato, a crop that could be grown abundantly in less favourable soil. Eventually, cows took over much of Ireland, leaving the native population virtually dependent on the potato for survival.

Despite being a major producer of beef, most of the people of Ireland during this period consumed little of the meat produced, in either fresh or salted form, due to its prohibitive cost. This was because most of the farms and their produce were owned by wealthy Anglo-Irish landlords (many of whom were often absent) and most of the population were from families of poor tenant farmers, with most of the corned beef being marked for export.

The lack of beef or corned beef in the Irish diet was especially true in the north of Ireland and areas away from the major centres for corned beef production. However, individuals living in these production centres such as Cork did consume the product to a certain extent. The majority of Irish who resided in Ireland at the time mainly consumed dairy products and meats such as pork or salt pork,[13] bacon and cabbage being a notable example of a traditional Irish meal.

20th century to present

Corned beef became a less important commodity in the 19th century Atlantic world, due in part to the abolition of slavery.[12] Corned beef production and its canned form remained an important food source during the Second World War. Much of the canned corned beef came from Fray Bentos in Uruguay, with over 16 million cans exported in 1943.[13] Today significant amounts of the global canned corned beef supply comes from South America. Approximately 80% of the global canned corned beef supply originates in Brazil.[15]

Cultural associations

In North America, corned beef dishes are associated with traditional British and Irish cuisines.[16]

Mark Kurlansky, in his book Salt, states that the Irish produced a salted beef around the Middle Ages that was the "forerunner of what today is known as Irish corned beef" and in the 17th century, the English named the Irish salted beef "corned beef".[17]

Before the wave of 19th century Irish immigration to the United States, many of the ethnic Irish did not consume corned beef dishes. The popularity of corned beef compared to back bacon among the immigrant Irish may have been due to corned beef being considered a luxury product in their native land, while it was cheap and readily available in the United States.[13]

The Jewish population produced similar corned beef brisket, also smoking it into pastrami. Irish immigrants often purchased corned beef from Jewish butchers.[13][18]

Canned corned beef has long been one of the standard meals included in military field ration packs globally, due to its simplicity and instant preparation. One example is the American Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE) pack. Astronaut John Young sneaked a contraband corned beef sandwich on board Gemini 3, hiding it in a pocket of his spacesuit.[19]

Regions

North America

In the United States and Canada, corned beef is typically available in two forms: a cut of beef (usually brisket, but sometimes round or silverside) cured or pickled in a seasoned brine, or cooked and canned.

Corned beef is often purchased ready to eat in Jewish delicatessens. It is the key ingredient in the grilled Reuben sandwich, consisting of corned beef, Swiss cheese, sauerkraut, and Thousand Island or Russian dressing on rye bread. Smoking corned beef, typically with a generally similar spice mix, produces smoked meat (or "smoked beef") such as pastrami or Montreal-style smoked meat.

Corned beef hashed with potatoes served with eggs is a common breakfast dish in the United States of America.

In both the United States and Canada, corned beef is sold in cans in minced form. It is also sold this way in Puerto Rico and Uruguay.

Newfoundland and Labrador

Corned beef is known specifically as "salt beef" in Newfoundland and Labrador, and is sold in buckets with brine to preserve the beef. It is a staple product culturally in Newfoundland and Labrador, providing a source of meat during their long winters. It is still commonly eaten in Newfoundland and Labrador, most often associated with the local Jiggs dinner meal. In recent years it has been used in different meals locally, such as a Jiggs dinner poutine dish.

Saint Patrick's Day

In the United States, consumption of corned beef is often associated with Saint Patrick's Day.[20] Corned beef is not an Irish national dish, and the connection with Saint Patrick's Day specifically originates as part of Irish-American culture, and is often part of their celebrations in North America.[21]

Corned beef was used as a substitute for bacon by Irish immigrants in the late 19th century.[22] Corned beef and cabbage is the Irish-American variant of the Irish dish of bacon and cabbage. A similar dish is the New England boiled dinner, consisting of corned beef, cabbage, and root vegetables such as carrots, turnips, and potatoes, which is popular in New England and another similar dish, Jiggs dinner, is popular in parts of Atlantic Canada.

Ireland

The appearance of corned beef in Irish cuisine dates to the 12th century in the poem Aislinge Meic Con Glinne or The Vision of MacConglinne.[23] Within the text, it is described as a delicacy a king uses to purge himself of the "demon of gluttony". Cattle, valued as a bartering tool, were only eaten when no longer able to provide milk or to work. The corned beef as described in this text was a rare and valued dish, given the value and position of cattle within the culture, as well as the expense of salt, and was unrelated to the corned beef eaten today.[24]

United Kingdom

In the UK, "corned beef" refers to minced and canned salt beef. Unminced corned beef is referred to as salt beef.

Caribbean

Multiple Caribbean nations have their own varied versions of canned corned beef as a dish, common in Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Barbados, and elsewhere.[25] With cans being less perishable, it's an effective food to import to tropical islands that will keep, despite the heat and humidity. Corned beef is a cheap, quick, and familiar low-effort comfort food that might be prepared for any meal of the day. As with other cuisines, cooks often improvise to add extra flavouring components (usually what they have around or left over) to their corned beef, including: onions, garlic, ketchup, black pepper, salt, oil (or other fat), corn, potatoes, tomatoes, cabbage, carrots, beans, hot and/or bell peppers, etc. It's very often served with a starch, such as rice, roti, bread, or potatoes. Due to its simplicity, many Caribbean children grow up thinking fondly of this dish.

Israel

In Israel, a canned corned beef called Loof was the traditional field ration of the Israel Defense Forces until the product's discontinuation in 2011. The name Loof derives from "a colloquially corrupt short form of 'meatloaf.'"[26] Loof was developed by the IDF in the late 1940s as a kosher form of bully beef, while similar canned meats had earlier been an important component of relief packages sent to Europe and Palestine by Jewish organizations such as Hadassah.[26]

Polynesia

In Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga, colonialism by western powers brought with them something that would change Polynesian diets—canned goods, including the highly prized corned beef. Natural disasters brought in food aid from New Zealand, Australia, and the US, then world wars in the mid-20th century, foreign foods became a bigger part of daily diets while retaining ancestral foods like taro and coconuts.[27] Both wet salt-brined beef and canned corned beef are differentiated. In Samoa, brined povi masima (lit. "salted beef") or canned pīsupo (lit. "pea soup," general term for canned foods). In Tonga, corned (wet brine) masima or canned meats kapa are typical.

Hong Kong

Corned beef has also become a common dish in Hong Kong cuisine, though it has been heavily adapted in style and preparation to fit local tastes. It is often served with other "Western" fusion cuisine at cha chaan teng and other cheap restaurants catering to locals. Like most localized "Western" food in East Asia, trade, imperialism, and war played roles in bringing and popularizing corned beef in Hong Kong.

Philippines

_-_Philippines_03.jpg.webp)

Along with other canned meats, canned corned beef is a popular breakfast staple in the Philippines.[28][29] Corned beef is also known as carne norte (alternative spelling: karne norte) locally, literally translating to "northern meat" in Spanish, the term refers to Americans, whom Filipinos referred then as norteamericanos, just like the rest of Spain's colonies, where there is a differentiation between what is norteamericano (Canadian, American, Mexicano) as there are between centroamericano (Nicaraguense, Costarricense et al.) and sudamericano (Colombiano, Equatoriano, Paraguayo, et al.). The colonial mindset distinction then of what was norteamericano was countries north of the Viceroy's Road (Camino de Virreyes), the route used to transport goods from the Manila Galleon landing in the port of Acapulco overland for Havana via the port of Veracruz (and not the Rio Grande river in Texas today), thus centroamericano meant the other Spanish possessions south of Mexico city.

Corned beef, especially the Libby's brand, first became popular during the American colonial period of the Philippines (1901–1941) among the wealthy as a luxury food; they were advertised serving the corned beef cold and straight-from-the-can on to a bed of rice, or as patties in between bread. During World War II (1942–1945), American soldiers brought for themselves, and airdropped from the skies the same corned beef; it was a life-or-death commodity since the Japanese Imperial Army forcibly controlled all food in an effort to subvert any resistance against them.

_-_Philippines_02.jpg.webp)

After the war (1946 to present), corned beef gained far more popularity. It remains a staple in balikbayan boxes and on Filipino breakfast tables. The ordinary Filipino can afford them, and many brands have sprung up, including those manufactured by Century Pacific Food, CDO Foodsphere and San Miguel Food and Beverage, which are wholly owned by Filipinos and locally manufactured.[28][29]

Philippine corned beef is typically made from shredded beef or buffalo meat, and is almost exclusively sold in cans. It is boiled, shredded, canned, and sold in supermarkets and grocery stores for mass consumption. It is usually served as the breakfast combination called "corned beef silog", in which corned beef is cooked as carne norte guisado (fried, mixed with onions, garlic, and often, finely cubed potatoes, carrots, tomatoes, and/or cabbage), with a side of sinangag (garlic fried rice), and a fried egg.[30][28][31] Another common way to eat corned beef is tortang carne norte (or corned beef omelet), in which corned beef is mixed with egg and fried.[32][33] Corned beef is also used as a cheap meat ingredient in dishes like sopas and sinigang.[34][35][36]

See also

- Potted meat – Form of traditional food preservation

- Curing salt

- Cured fish

References

- "Corned Beef". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- US Dept of Agriculture. "Clostridium botulinum" (PDF). Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- "Ingested Nitrates and Nitrites, and Cyanobacterial Peptide Toxins". NCBI.NLM.NIH.gov. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Ewbank, Mary (March 14, 2018). "The Mystery of New England's Gray Corned Beef". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- Cook, Alexander (2004). "Sailing on The Ship: Re-enactment and the Quest for Popular History". History Workshop Journal. 57 (57): 247–255. doi:10.1093/hwj/57.1.247. hdl:1885/54218. JSTOR 25472737. S2CID 194110027.

- McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and lore of the Kitchen. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1.

- "Corn, n.1". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2010. "A small hard particle, a grain, as of sand or salt."

- Norris, James F. (1921). A Textbook of Inorganic Chemistry for Colleges. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 528. OCLC 2743191.

Potassium nitrate is used in the manufacture of gunpowder ... It is also used in curing meats; it prevents putrefaction and produces the deep red color familiar in the case of salted hams and corned beef.

- Theiss, Lewis Edwin (January 1911). "Every Day Foods That Injure Health". Pearson's Magazine. New York: Pearson Pub. Co. 25: 249.

you have probably noticed how nice and red corned beef is. That's because it has in it saltpeter, the same stuff that is used in making gunpowder.

- Hessler, John C.; Smith, Albert L. (1902). Essentials of Chemistry. Boston: Benj. H. Sanborn & Co. p. 158.

The chief use of potassium nitrate as a preservative is in the preparation of 'corned' beef.

- Cook, Alexander (2004). "Sailing on The Ship: Re-enactment and the Quest for Popular History". History Workshop Journal. 57 (57): 247–255. doi:10.1093/hwj/57.1.247. hdl:1885/54218. JSTOR 25472737. S2CID 194110027.

- Mandelblatt, Bertie (2007). "A Transatlantic Commodity: Irish Salt Beef in the French Atlantic World". History Workshop Journal. 63 (1): 18–47. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbm028. JSTOR 25472901. S2CID 140660191.

- Mac Con Iomaire, Máirtín; Óg Gallagher, Pádraic (2011). "Irish Corned Beef: A Culinary History". Journal of Culinary Science and Technology. 9 (1): 27–43. doi:10.1080/15428052.2011.558464. S2CID 216138899.

- Rifkin, Jeremy (March 1, 1993). Beyond Beef: The Rise and Fall of the Cattle Culture. Plume. pp. 56, 57. ISBN 978-0-452-26952-1.

- Palmeiras, Rafael (September 9, 2011). "Carne enlatada brasileira representa 80% do consumo mundial". Brasil Econômico. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- "The History Behind All Your Favorite St. Patrick's Day Foods". February 27, 2019.

- Kurlansky, Mark (2002). Salt: A World History. New York: Penguin. pp. 124–127. ISBN 978-0-14-200161-5.

- Brown, Alton (2007). "Pickled Pink". Good Eats. Food network. 10 (18).

- Fessenden, Marissa (March 25, 2015). "That Time an Astronaut Smuggled a Corned Beef Sandwich To Space". Smithsonian.com.

- "Is corned beef and cabbage an Irish dish? No! Find out why..." European Cuisines. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- Lam, Francis (March 17, 2010). "St. Patrick's Day controversy: Is corned beef and cabbage Irish?". Salon.com. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- "St. Patrick's Day Traditions". history.com.

- "Aislinge Meic Con Glinne". The University College Cork Ireland.

- "Ireland: Why We Have No Corned Beef & Cabbage Recipes". European Cuisines.

- "Puerto Rican Canned Corned Beef Stew".

- Soclof, Adam (November 23, 2011). "As IDF bids adieu to Loof, a history of 'kosher Spam'". JWeekly.com.

- Hillyer, Garrett. "Back to the Future' for Samoan Food". eCampusOntario PressBooks.

- Makalintal, Bettina (January 4, 2019). "Palm Corned Beef is My Favorite Part of Filipino Breakfast". vice.com.

- "Why corned beef isn't just for breakfast". cnnphilippines.com. January 26, 2018.

- Manalo, Lalaine (August 14, 2021). "Ginisang Corned Beef". Kawaling Pinoy. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- "Corned Beef with Potato". Casa Baluarte Filipino Recipes. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- "Tortang Carne Norte Tortang Carne Norte". Overseas Pinoy Cooking. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- "Corned Beef Omelet". Panlasang Pinoy. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- "Sinigang na Corned Beef Recipe". What To Eat Philippines. September 12, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- "Sinigang na Corned Beef". Ang Sarap. August 4, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- Angeles, Mira. "Sopas with Corned Beef Recipe". Yummy.ph. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

.jpg.webp)