Animal slaughter

Animal slaughter is the killing of animals, usually referring to killing domestic livestock. It is estimated that each year, 80 billion land animals are slaughtered for food.[1] Most animals are slaughtered for food; however, they may also be slaughtered for other reasons such as for harvesting of pelts, being diseased and unsuitable for consumption, or being surplus for maintaining a breeding stock. Slaughter typically involves some initial cutting, opening the major body cavities to remove the entrails and offal but usually leaving the carcass in one piece. Such dressing can be done by hunters in the field (field dressing of game) or in a slaughterhouse. Later, the carcass is usually butchered into smaller cuts.

| Animals | Number Killed |

|---|---|

| Chickens | 72,118,779,000 |

| Ducks | 3,311,899,000 |

| Pigs | 1,348,541,419 |

| Geese | 723,648,000 |

| Turkeys | 635,955,000 |

| Rabbits | 633,013,000 |

| Sheep | 602,319,130 |

| Goats | 502,808,495 |

| Cattle | 324,518,029 |

| Rodents | 70,977,000 |

| Pigeons and other birds | 46,216,000 |

| Water buffalo | 27,692,388 |

| Horses | 4,940,693 |

| Camels | 2,991,884 |

| Donkeys | 1,958,602 |

| Other camelids | 967,656 |

| Deer | 628,542 |

| Mules | 130,804 |

The animals most commonly slaughtered for food are cattle and water buffalo, sheep, goats, pigs, deers, horses, poultry (mainly chickens, turkeys, ducks and geese), insects (a commercial species is the house cricket), and increasingly, fish in the aquaculture industry (fish farming). In 2020, Faunalytics reported that the countries with the largest number of slaughtered cows and chickens are China, the United States, and Brazil. Concerning pigs, they are slaughtered by far the most in China, followed by the United States, Germany, Spain, Vietnam, and Brazil. For sheep, again China slaughtered the most, this time followed by Australia and New Zealand. Similarly, the amount (in tonnes) of fish used for production is highest in China, Indonesia, Peru, India, Russia, and the United States (in that order).[2]

Modern history

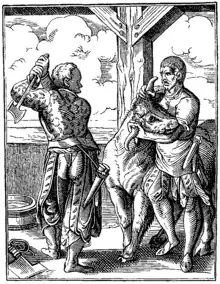

The use of a sharpened blade for the slaughtering of livestock has been practised throughout history. Prior to the development of electric stunning equipment, some species were killed by simply striking them with a blunt instrument, sometimes followed by exsanguination with a knife.

The belief that this was unnecessarily cruel and painful to the animal eventually led to the adoption of specific stunning and slaughter methods in many countries. One of the first campaigners on the matter was the eminent physician, Benjamin Ward Richardson, who spent many years of his later working life developing more humane methods of slaughter as a result of attempting to discover and adapt substances capable of producing general or local anaesthesia to relieve pain in people. As early as 1853, he designed a chamber that could kill animals by gassing them. He also founded the Model Abattoir Society in 1882 to investigate and campaign for humane methods of slaughter and experimented with the use of electric current at the Royal Polytechnic Institution.[3]

The development of stunning technologies occurred largely in the first half of the twentieth century. In 1911, the Council of Justice to Animals (later the Humane Slaughter Association, or HSA) was established in England to improve the slaughter of livestock.[4] In the early 1920s, the HSA introduced and demonstrated a mechanical stunner, which led to the adoption of humane stunning by many local authorities.[5]

The HSA went on to play a key role in the passage of the Slaughter of Animals Act 1933. This made the mechanical stunning of cows and electrical stunning of pigs compulsory, with the exception of Jewish and Muslim meat.[5][6] Modern methods, such as the captive bolt pistol and electric tongs were required, and the act's wording specifically outlawed the poleaxe. The period was marked by the development of various innovations in slaughterhouse technologies, not all of them particularly long-lasting.

Methods

Stunning

Various methods are used to kill or render an animal unconscious during animal slaughter.

- Electrical (stunning or slaughtering with electric current known as electronarcosis)

- This method is used for swine, sheep, calves, cattle, and goats. Current is applied either across the brain or the heart to render the animal unconscious before being killed. In industrial slaughterhouses, chickens are killed prior to scalding by being passed through an electrified water-bath while shackled.[7]

- Gaseous (carbon dioxide)

- This method can be used for sheep, calves and swine. The animal is asphyxiated by the use of CO2 gas before being killed. In several countries, CO2 stunning is mainly used on pigs. A number of pigs enter a chamber which is then sealed and filled with 80% to 90% CO2 in air. The pigs lose consciousness within 13 to 30 seconds. Older research produced conflicting results, with some showing pigs tolerated CO2 stunning and others showing they did not.[8][9][10] However, the current scientific consensus is that the "inhalation of high concentration of carbon dioxide is aversive and can be distressing to animals."[11] Nitrogen has been used to induce unconsciousness, often in conjunction with CO2. Domestic turkeys are averse to high concentrations of CO2 (72% CO2 in air) but not low concentrations (a mixture of 30% CO2 and 60% argon in air with 3% residual oxygen).[12]

- Mechanical (captive bolt pistol)

- This method can be used for sheep, swine, goats, calves, cattle, horses, mules, and other equines. A captive bolt pistol is applied to the head of the animal to quickly render them unconscious before being killed. There are three types of captive bolt pistols, penetrating, non-penetrating and free bolt. The use of penetrating captive bolts has largely been discontinued in commercial situations to minimize the risk of transmission of disease when parts of the brain enter the bloodstream.

- Firearm (gunshot/free bullet)

- This method can be used for cattle, calves, sheep, swine, goats, horses, mules, and other equines. It is also the standard method for taking down wild game animals such as deer with the intention of consuming their meat. A conventional firearm is used to fire a bullet into the brain or through the heart of the animal to render the animal quickly unconscious (and presumably dead).

Killing

- Exsanguination

- The animal either has its throat cut or has a chest stick inserted cutting close to the heart. In both these methods, main veins and/or arteries are cut and allowed to bleed.[13][14]

- Manual

- Used on poultry and other animals; different methods are practiced, here are some examples: a) grabbing the bird by the head then snapping its neck using quick and fast movements b) the bird is put upside down inside a metal funnel, then the head is either quickly cut or hit using the back end of a machete or knife. c) cattle, sheep and goats are tied then struck multiple times in the head with a sledgehammer until the animal dies or loses consciousness.

- Drug administration

- Drug administration is used to ensure the animal is dead. However, being that this method is expensive, time-consuming, and renders the animals' bodies toxic and inedible, it is mainly used for animal euthanasia, not as a commercialized slaughter method.

Preslaughter handling

Whether animals are humanely stunned before slaughter or not, they can suffer stress while waiting to be killed.[15] A 1996 veterinary review found that there are many ways in which animals suffer and die during the preslaughter period. They include:

- Dehydration: Animals may not be provided with water at market or during their journey to the slaughterhouse and may arrive dehydrated. The effects of severe dehydration include severe thirst, nausea, a hot-dry body, dry tongue, loss of co-ordination and concentrated urine of a small volume.

- Emotional stress during transport: The unfamiliarity of being on board a transport truck causes fear in animals, and if they are cooped up with others who they do not know, they may start fighting. The noise and jolting of the truck also causes stress and cows, pigs, horses and birds are at particular risk of suffering from motion sickness.

- Temperature stress during transport: Some animals die because of the heat that develops in the closely confined conditions on board the transport truck. During transport, animals are not able to express all the behaviors which normally allow them to keep cool like seeking shade, wallowing, licking their fur or stretching their wings and legs. During transport the only useful way they can dissipate heat is by panting. In colder climates, the animals can be exposed to extreme low temperatures, resulting in hypothermia.

- Torn skin, bruising and injury: Caused by rough handling of animals, such as beating the animals with sticks when they refuse to move forward or dragging them along the ground when they fall down. The insults which lead to bruising may be painful, and the swelling and inflammation associated with a bruise lead to a longer-lasting pain.

- Sickness and disease: Farmers vary between countries in their attitude as to which sick and diseased animals can be sent for slaughter. Some take the view that the slaughterhouses are expert at salvaging what they can from carcasses and so most diseased animals are sent in, whereas in other countries farmers appreciate that diseased stock are low grade and their likely low return does not justify sending them in. Sickness and disease are two of the most serious forms of animal suffering and transporting seriously ill animals imposes an additional stress.

- Fecal soiling: In some countries, especially where animals come off lush pasture, transport is the main period when they pick up body surface fecal contamination. The emotional stress associated with transport no doubt induces defecation and this compounds the problem.

National laws

Europe

The measures for sanitary checks, animal welfare protection and slaughtering procedures are harmonised throughout the European Union, and detailed by the European Commissions' regulations CE 853/2004, 854/2004 and 1099/2009.

Canada

In Canada, the handling and slaughter of food animals is a shared responsibility of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), industry, stakeholders, transporters, operators and every person who handles live animals. Canadian law requires that all federally registered slaughter establishments ensure that all species of food animals are handled and slaughtered humanely. The CFIA verifies that federal slaughter establishments are compliant with the Meat Inspection Regulations. The CFIA's humane slaughter requirements take effect when the animals arrive at the federally registered slaughter establishment. Industry is required to comply with the Meat Inspection Regulations for all animals under their care. The Meat Inspection Regulations define the conditions for the humane slaughter of all species of food animals in federally registered establishments. Some of the provisions contained in the regulations include:

- guidelines and procedures for the proper unloading, holding and movement of animals in slaughter facilities

- requirements for the segregation and handling of sick or injured animals

- requirements for the humane slaughter of food animals[16]

United Kingdom

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) is the main governing body responsible for legislation and codes of practice covering animal slaughter in the UK.

In the UK the methods of slaughter are largely the same as those used in the United States with some differences. The use of captive bolt equipment and electrical stunning are approved methods of stunning sheep, goats, cattle and calves for consumption[14]- with the use of gas reserved for swine.[17]

Until 2004, it was illegal to slaughter animals in sight of their conspecifics (members of the same species) because it was thought to cause them distress. However, there was a concern that moving the animals away from their conspecifics to a different place to be slaughtered would increase the stun-to-kill time (time between stunning the animal and killing it) for the stunned animal, increasing the risk the animal would regain consciousness and it was consequently recommended that slaughter in front of conspecifics be permitted alongside a mandatory limit on stun-to-kill time. Legislation was introduced which allowed animals to be slaughtered in sight of their conspecifics but there was no legislation for a legal maximum stun-to-kill time. Some critics argue that this resulted in the "worst of both worlds", as it mean that the slaughter methods now caused distress to conspecifics without reliably ensuring the animals were killed before regaining consciousness.[18]

United States

In the United States, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) specifies the approved methods of livestock slaughter:[19]

Each of these methods is outlined in detail, and the regulations require that inspectors identify operations which cause "undue" "excitement and discomfort" of animals.

In 1958, the law that is enforced today by the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) was passed as the Humane Slaughter Act of 1958. This Act requires the proper treatment and humane handling of all food animals slaughtered in USDA inspected slaughter plants. It does not apply to chickens or other birds.[20]

4D Meat

Meat from animals which are dead, diseased, disabled or dying (4-D meat) on the arrival at the slaughterhouse is often salvaged for rendering,[21] and used by a wide range of industries including pet food manufacturers, zoos, greyhound kennels, and mink ranches.[22]

The U.S. Code (Title 21, Chapter 12, Subchapter II, § 644) [23] Regulates transactions, transportation, or importation of 4–D animals to prevent use as human food:

"No person, firm, or corporation engaged in the business of buying, selling, or transporting in commerce, or importing, dead, dying, disabled, or diseased animals, or any parts of the carcasses of any animals that died otherwise than by slaughter, shall buy, sell, transport, offer for sale or transportation, or receive for transportation, in commerce, or import, any dead, dying, disabled, or diseased cattle, sheep, swine, goats, horses, mules or other equines, or parts of the carcasses of any such animals that died otherwise than by slaughter, unless such transaction, transportation or importation is made in accordance with such regulations as the Secretary may prescribe to assure that such animals, or the unwholesome parts or products thereof, will be prevented from being used for human food purposes."

The 2004 report to US Congress titled “Animal Rendering: Economics and Policy”,[24] available in the library of Congressional Research Service, in the ‘Introduction’ paragraph explains Renderers in the US and Canada convert dead animals and other waste material into sellable products:

“Renderers convert dead animals and animal parts that otherwise would require disposal into a variety of materials, including edible and inedible tallow and lard and proteins such as meat and bone meal (MBM). These materials in turn are exported or sold to domestic manufacturers of a wide range of industrial and consumer goods such as livestock feed and pet food, soaps, pharmaceuticals, lubricants, plastics, personal care products, and even crayons.”

Although some authors have found health problems associated with the consumption of 4D meat by certain species in its raw form,[25] or found it potentially hazardous,[26] FDA considers it fit for animal consumption:

"Pet food consisting of material from diseased animals or animals which have died otherwise than by slaughter, which is in violation of 402(a)(5) will not ordinarily be actionable, if it is not otherwise in violation of the law. It will be considered fit for animal consumption."[27]

Religious laws

Ritual slaughter is the overarching term accounting for various methods of slaughter used by religions around the world for food production. While keeping religious autonomy, these methods of slaughter, within the United States, are governed by the Humane Slaughter Act and various religion-specific laws, most notably, Shechita and Dhabihah.

Jewish law (Shechita)

Animal slaughter in Judaism falls in accordance to the religious law of Shechita. In preparation, the animal being prepared for slaughter must be considered kosher (fit) before the act of slaughter can commence and consumed. The basic law of the Shechita process requires the rapid and uninterrupted severance of the major vital organs and vessels. They slit the throat, resulting in a quick drop in blood pressure, restricting blood to the brain. This abrupt loss of pressure results in the rapid and irreversible cessation of consciousness and sensibility to pain (a requirement held in high regard by most institutions).[28]

Islamic law (Dhabihah)

Animal slaughtering in Islam is in accordance with the Qur’an. To slaughter an animal is to cause it to pass from a living state to a dead state. For the meat to be lawful (Halal) according to Islam, it must come from an animal which is a member of a lawful species and it must be ritually slaughtered, i.e. according to the Law, or the sole code recognized by the group as legitimate. The animal is killed in ways similar to the Jewish ritual with the throat being slit (dhabh), resulting in a quick drop in blood pressure, restricting blood to the brain. This abrupt loss of pressure results in the rapid and irreversible cessation of consciousness and sensibility to pain (a requirement held in high regard by most institutions). The slaughterer must say Bismillah (In the name of Allah/God) before slaughtering the animal.[29] Blood must be drained out of the carcass.[30]

Sikh customs (Jhatka)

The practice of Jhatka in India developed out of the Sikh tradition in accordance with the value of Ahimsa (no harm). Sikhs believe that an animal should be slaughtered quickly and with as little pain as possible in order to reduce bad Karma that may result from such a practice. In India today most establishments will provide both Halal and Jhatka options for dishes containing chicken and lamb. Jhatka meat is not widely available outside India. Jhatka meat is also often considered to be the preferred method of slaughter for Sikhs in India and abroad.

Effects on livestock workers

In 2010, Human Rights Watch described slaughterhouse line work in the United States as a human rights crime.[31] Slaughterhouses in the United States commonly illegally employ and exploit underage workers and illegal immigrants.[32][33] In a report by Oxfam America, slaughterhouse workers were observed not being allowed breaks, were often required to wear diapers, and were paid below minimum wage.[34]

American slaughterhouse workers are three times more likely to suffer serious injury than the average American worker.[35] NPR reports that pig and cattle slaughterhouse workers are nearly seven times more likely to suffer repetitive strain injuries than average.[36] The Guardian reports that on average there are two amputations a week involving slaughterhouse workers in the United States.[37] On average, one employee of Tyson Foods, the largest meat producer in America, is injured and amputates a finger or limb per month.[38] The Bureau of Investigative Journalism reported that over a period of six years, in the UK 78 slaughter workers lost fingers, parts of fingers or limbs, more than 800 workers had serious injuries, and at least 4,500 had to take more than three days off after accidents.[39] In a 2018 study in the Italian Journal of Food Safety, slaughterhouse workers are instructed to wear ear protectors to protect their hearing from the constant screams of animals being killed.[40] A 2004 study in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine found that "excess risks were observed for mortality from all causes, all cancers, and lung cancer" in workers employed in the New Zealand meat processing industry.[41]

The worst thing, worse than the physical danger, is the emotional toll. If you work in the stick pit [where hogs are killed] for any period of time—that let’s [sic] you kill things but doesn't let you care. You may look a hog in the eye that's walking around in the blood pit with you and think, ‘God, that really isn't a bad looking animal.’ You may want to pet it. Pigs down on the kill floor have come up to nuzzle me like a puppy. Two minutes later I had to kill them – beat them to death with a pipe. I can't care.

— Gail A. Eisnitz, [42]

The act of slaughtering animals, or of raising or transporting animals for slaughter, may engender psychological stress or trauma in the people involved.[43][44][45] A 2016 study in Organization indicates, "Regression analyses of data from 10,605 Danish workers across 44 occupations suggest that slaughterhouse workers consistently experience lower physical and psychological well-being along with increased incidences of negative coping behavior."[46] A 2009 study by criminologist Amy Fitzgerald indicates, "slaughterhouse employment increases total arrest rates, arrests for violent crimes, arrests for rape, and arrests for other sex offenses in comparison with other industries."[47] As authors from the PTSD Journal explain, "These employees are hired to kill animals, such as pigs and cows that are largely gentle creatures. Carrying out this action requires workers to disconnect from what they are doing and from the creature standing before them. This emotional dissonance can lead to consequences such as domestic violence, social withdrawal, anxiety, drug and alcohol abuse, and PTSD."[48]

Public attitudes

Even though around 90% of US adults regularly consume meat,[49] almost half of them appear to support a ban on slaughterhouses: in Sentience Institute’s 2017 survey on attitudes towards animal farming with 1,094 US adults 49% of them "support a ban on factory farming, 47% support a ban on slaughterhouses, and 33% support a ban on animal farming”.[50][51][52] The 2017 survey was replicated by researchers at the Oklahoma State University, who found similar results. They also got 73% of respondents answering “yes” to the question “Were you aware that slaughterhouses are where livestock are killed and processed into meat, such that, without them, you would not be able to consume meat?”.[53][54]

In the United States, many public protest slaughters were held in the late 1960s and early 1970s by the National Farmers Organization. Protesting low prices for meat, farmers would kill their own animals in front of media representatives. The carcasses were wasted and not eaten. However, this effort backfired because it angered television audiences to see animals being needlessly and wastefully killed.[55]

Animal welfare

| Part of a series on |

| Animal rights |

|---|

There has been controversy over whether or not animals should be slaughtered and over the various methods used. Some people believe sentient beings should not be harmed regardless of the purpose, or that meat production is an insufficient justification for harm.[56]

Religious slaughter laws and practices have always been a subject of debate, and the certification and labeling of meat products remain to be standardized. Animal welfare concerns are being addressed to improve slaughter practices by providing more training and new regulations. There are differences between conventional and religious slaughter practices, although both have been criticized on grounds of animal welfare. Concerns about religious slaughter focus on the stress caused during the preparation stages before the slaughtering, pain and distress that may be experienced during and after the neck cutting and the worry of a prolonged period of time of lost brain function during the points between death and preparation if a stunning technique such as electronarcosis is not applied.[57]

See also

- Animal sacrifice

- Carnism

- Controlled-atmosphere killing

- Fish slaughter

- Horse slaughter

- Ike jime, a Japanese method of slaughtering fish

- Meat

- Pig slaughter

- Udhiyyah or Qurbani, the sacrifice of a livestock animal according to Islamic law

References

- "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- "Global Animal Slaughter Statistics & Charts: 2020 Update". 29 July 2020. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Power, D'Arcy (1901). "Richardson, Benjamin Ward". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Power, D'Arcy (1901). "Richardson, Benjamin Ward". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co. - "Humane Slaughter Association Newsletter March 2011" (PDF). Humane Slaughter Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- "History of the HSA". Humane Slaughter Association. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- Leese, Arnold. "The Legalised Cruelty Of Shechita: The Jewish Method Of Cattle-Slaughter". Archived from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- Mead, G.C., ed. (2004). Poultry meat processing and quality. Cambridge: Woodhead Pub. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-85573-903-1. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- "When is carbon dioxide stunning used in abattoirs?". RSPCA. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- Jongman, E.C; Barnett, J.L; Hemsworth, P.H (2000). "The aversiveness of carbon dioxide stunning in pigs and a comparison of the CO2 stunner crate vs. The V-restrainer". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 67 (1–2): 67–76. doi:10.1016/s0168-1591(99)00103-3. PMID 10719190.

- Raj, A. B. Mohan; Gregory, N. G. (November 1995). "Welfare Implications of the Gas Stunning of Pigs 1. Determination of Aversion to the Initial Inhalation of Carbon Dioxide or Argon". Animal Welfare. 4 (4): 273–280. doi:10.1017/S096272860001798X. S2CID 255798100.

- "Stunning of Pigs with Carbon Dioxide" (PDF). International Coalition For Animal Welfare. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2019.

- Raj, A. B. M. (1996). "Aversive reactions of turkeys to argon, carbon dioxide and a mixture of carbon dioxide and argon". Veterinary Record. 138 (24): 592–593. doi:10.1136/vr.138.24.592. PMID 8799986. S2CID 34896415.

- "Farmed animal welfare: Slaughter". Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. 3 September 2009. Archived from the original on 26 September 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- "Slaughter Red". Hsa.org.uk. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Gregory, N. G. (1 January 1996). "Welfare and hygiene during preslaughter handling". Meat Science. Meat for the Consumer 42 International Congress of MEAT Science and Technology. 43: 35–46. doi:10.1016/0309-1740(96)00053-8. ISSN 0309-1740. PMID 22060639.

- "Humane Handling and Slaughter of Food Animals in Canada". Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 16 March 2013. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "Pig Slaughter". Hsa.org.uk. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Aid, Animal. "The humane slaughter myth." (2009), page 16

- "Humane Slaughter of Livestock Regulations (National Citation: 9 C.F.R. 313.1 – 90)". Animal Legal and Historical Center (regulations from USDA). 2007. Archived from the original on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- "Humane Methods of Slaughter Act". National Agricultural Library. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "4D meat". Medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "Compliance Policy Guides –CPG Sec. 690.500 Uncooked Meat for Animal Food". Fda.gov. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "21 U.S. Code § 644 – Regulation of transactions, transportation, or importation of 4–D animals to prevent use as human food". Law.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- S., Becker, Geoffrey (17 March 2004). "Animal Rendering: Economics and Policy". Digital Library. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "THE USE OF "4-D MEAT" IN THE GREYHOUND RACING INDUSTRY" (PDF). Grey2kusa.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- "Meat-based diets". Vegepets.info. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "FDA Compliance Policy Guide Sec. 690.300 about Canned Pet Food". Fda.gov. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- Jones, Sam. "Halal, shechita and the politics of animal slaughter". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Benkheira, Mohammed (2000). "Artificial death, canonical death: Ritual slaughter in Islam". Food and Foodways. 4. 8 (4): 227–252. doi:10.1080/07409710.2000.9962092. S2CID 143164349. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Jones, Sam. "Halal, shechita and the politics of animal slaughter". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Varia, Nisha (11 December 2010). "Rights on the Line". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Waldman, Peter (29 December 2017). "America's Worst Graveyard Shift Is Grinding Up Workers". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Grabell, Michael (1 May 2017). "Exploitation and Abuse at the Chicken Plant". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Grabell, Michael (23 May 2018). "Live on the Live". Oxfam America. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "Meatpacking". Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Lowe, Peggy (11 August 2016). "Working 'The Chain,' Slaughterhouse Workers Face Lifelong Injuries". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "Two amputations a week: the cost of working in a US meat plant". The Guardian. 5 July 2018. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Lewis, Cora (18 February 2018). "America's Largest Meat Producer Averages One Amputation Per Month". Buzzfeed News. Archived from the original on 13 June 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "Revealed: Shocking safety record of UK meat plants". The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. 29 July 2018. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Francesca Iulietto, Maria; Sechi, Paola (3 July 2018). "Noise assessment in slaughterhouses by means of a smartphone app". Italian Journal of Food Safety. 7 (2): 7053. doi:10.4081/ijfs.2018.7053. PMC 6036995. PMID 30046554.

- McLean, D; Cheng, S (June 2004). "Mortality and cancer incidence in New Zealand meat workers". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 61 (6): 541–547. doi:10.1136/oem.2003.010587. PMC 1763658. PMID 15150395.

- Eisnitz, Gail A. (1997). Slaughterhouse: : The Shocking Story of Greed, Neglect, And Inhumane Treatment Inside the U.S. Meat Industry. Prometheus Books.

- "Sheep farmer who felt so guilty about driving his lambs to slaughter rescues them and becomes a vegetarian". The Independent. 30 January 2019. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- Victor, Karen; Barnard, Antoni (20 April 2016). "Slaughtering for a living: A hermeneutic phenomenological perspective on the well-being of slaughterhouse employees". International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 11: 30266. doi:10.3402/qhw.v11.30266. PMC 4841092. PMID 27104340.

- "Working 'The Chain,' Slaughterhouse Workers Face Lifelong Injuries". Npr.org. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- Baran, B. E.; Rogelberg, S. G.; Clausen, T (2016). "Routinized killing of animals: Going beyond dirty work and prestige to understand the well-being of slaughterhouse workers". Organization. 23 (3): 351–369. doi:10.1177/1350508416629456. S2CID 148368906.

- Fitzgerald, A. J.; Kalof, L. (2009). "Slaughterhouses and Increased Crime Rates: An Empirical Analysis of the Spillover From "The Jungle" Into the Surrounding Community". Organization & Environment. 22 (2): 158–184. doi:10.1177/1350508416629456. S2CID 148368906. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "The Psychological Damage of Slaughterhouse Work". PTSDJournal. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Berg, Jennifer; Jackson, Chris (12 May 2021). "Nearly nine in ten Americans consume meat as part of their diet". Ipsos. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- Ettinger, Jill (21 November 2017). "70% of Americans Want Better Treatment for Farm Animals, Poll Finds". Organic Authority. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- Piper, Kelsey (5 November 2018). "California and Florida voters could change the lives of millions of animals on Election Day". Vox. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- Reese Anthis, Jacy (20 November 2017). "Animals, Food, and Technology (AFT) Survey 2017". Sentience Institute. Surveys. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- Siegner, Cathy (25 January 2018). "Survey: Most consumers like meat, slaughterhouses not so much". Food Dive. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- Norwood, Bailey; Murray, Susan. "FooDS Food Deman Survey, Volume 5, Issue 9: January 18, 2018" (PDF). Oklahoma State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- Stockwell, Ryan J. Growing a new agrarian myth: the american agriculture movement, identity, and the call to save the family farm (Thesis). p. 19. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Browning, Heather; Veit, Walter (5 May 2020). "Is humane slaughter possible?". Animals. 10 (5): 799. doi:10.3390/ani10050799. PMC 7278393. PMID 32380765.

- Anil, M. Haluk (July 2012). "Religious slaughter: A current controversial animal welfare issue". Animal Frontiers. 2 (3): 64–67. doi:10.2527/af.2012-0051.

External links

- Canada Agricultural Products Act R.S., 1985, c. 20 (4th Supp.) Archived 31 August 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Humane Slaughter of Livestock Regulations

- Slovak Pig Slaughter and Traditional Sausage Making – article in English with detailed pictures of a Slovak family slaughtering a pig in the traditional style

- Live Counter About Slaughtered Animals Worldwide