The Lives of Animals

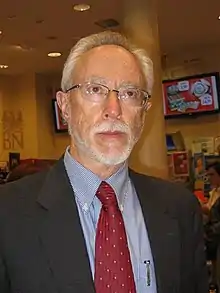

The Lives of Animals (1999) is a metafictional novella about animal rights by the South African novelist J. M. Coetzee, recipient of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Literature.[1] The work is introduced by Amy Gutmann and followed by a collection of responses by Marjorie Garber, Peter Singer, Wendy Doniger and Barbara Smuts.[2] It was published by Princeton University Press as part of its Human Values series.

| |

| Author | J. M. Coetzee, with responses by Marjorie Garber, Peter Singer, Wendy Doniger, Barbara Smuts |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Series | Human Values series |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Publisher | Princeton University Press |

Publication date | 1999 |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 127 pp |

| ISBN | 0-691-07089-X |

The Lives of Animals consists of two chapters, "The Philosophers and the Animals" and "The Poets and the Animals," first delivered by Coetzee as guest lectures at Princeton on 15 and 16 October 1997, part of the Tanner Lectures on Human Values.[3] The Princeton lectures consisted of two short stories (the chapters of the book) featuring a recurring character, the Australian novelist Elizabeth Costello, Coetzee's alter ego. Costello is invited to give a guest lecture to the fictional Appleton College in Massachusetts, just as Coetzee is invited to Princeton, and chooses to discuss not literature, but animal rights, just as Coetzee does.[4]

In having Costello deliver the arguments within his lectures, Coetzee plays with form and content, and leaves ambiguous to what extent the views are his own. The Lives of Animals appears again in Coetzee's novel Elizabeth Costello (2003).[5]

Coetzee's novella discusses the foundations of morality, the need of human beings to imitate one another, to want what others want, leading to violence and a parallel need to scapegoat non-humans. He appeals to an ethic of sympathy, not rationality, in our treatment of animals, to literature and the poets, not philosophy.[6] Costello tells her audience: "Sympathy has everything to do with the subject and little to do with the object ... There are people who have the capacity to imagine themselves as someone else, there are people who have no such capacity ... and there are people who have the capacity but choose not to exercise it. ... There are no bounds to the sympathetic imagination."[7]

Synopsis

The Lives of Animals

Elizabeth Costello is invited to Appleton College's annual literary seminar as a guest lecturer, much as Coetzee was invited to Princeton. Despite her stature as a celebrated novelist (much like Coetzee), she opts not to give lectures on literature or writing, but on animal cruelty.[8] Much like Coetzee, Costello is a vegetarian and abhors industries that experiment on and slaughter animals.[9]

The story is framed by a narrative involving Costello and her son, John Bernard, who happens to be a junior professor at Appleton. Costello's relationship with Bernard is strained, and her relationship with John’s wife, Norma, even more so.[8] Bernard was not instrumental in bringing his mother to campus. In fact, the university's leaders were unaware of Bernard's relationship with Costello when they issued the invitation. Bernard’s fears that his mother’s presence and opinions will be polarizing and controversial are entirely prophetic. In his private thoughts, he more than once wishes she had not accepted Appleton’s invitation.[10] Costello gives two lectures, then contributes to a debate with Appleton philosophy professor Thomas O’Hearne.

"The Philosophers and the Animals"

Costello's first lecture begins with an analogy between the Holocaust and the exploitation of animals. Costello makes the point that, just as residents in the neighborhoods of the death camps knew what was happening at the camps, but chose to turn a blind eye, so it is common practice today for otherwise respectable members of society to turn a blind eye to industries that bring pain and death to animals. This turns out to be the most controversial thing that Costello says during her visit, and it causes a Jewish professor of the college to boycott the dinner held in her honor. In her first lecture, Costello also moves to reject reason as the preeminent quality that separates humans from animals and allows humans to treat animals as less than the equals of humans. She proposes that reason might simply be a species specific trait, "the specialism of a rather narrow self-regenerating intellectual tradition ... which for its own motives it tries to install at the center of the universe."[11]

At the same time that Costello rejects reason as the premier human distinction, she also challenges the assumption that animals do not possess reason. Her argument rests on the fact that, while science cannot prove that animals do abstract thinking, it also cannot prove that they do not. In support of this argument, Costello summarizes an ape experiment that was conducted in the 1920s by Wolfgang Kohler. The principal player in the experiment was an ape named Sultan who was variously deprived of his bananas until he reasoned his way into obtaining them. Faced with the challenge of stacking several crates into a makeshift ladder, in order to reach the bananas that have been suspended above his reach, Sultan succeeds in demonstrating this elementary form of reasoning.[12]

What Costello objects to, however, is the basic inanity of the exercise which in no way explores any higher intellectual functions that Sultan might be capable of. The experiment, Costello objects, ignores any emotional hurt or confusion that the ape might be experiencing in favor of concentrating on what is, after all, a very elemental task. The ape might be thinking about the human who has constructed these tests: "What is wrong with him, what misconception does he have of me, that leads him to believe it is easier for me to reach a banana hanging from a wire than to pick up a banana from the floor?" Animal experiments, Costello concludes, fail to measure anything of real interest, because they ask the wrong questions and ignore the more interesting ones: "a carefully plotted psychological regimen conducts him [Sultan] away from ethics and metaphysics toward the humbler reaches of practical reason."[12]

"The Poets and the Animals"

In her second lecture, Costello suggests that humans can come to understand or "think their way into" the nature of animals through poetic imagination. As examples, she invokes Rilke's "The Panther" and Ted Hughes's "The Jaguar" and "Second Glance at a Jaguar."[13] "By bodying forth the jaguar," Costello says, "Hughes shows us that we too can embody animals – by the process called poetic invention that mingles breath and sense in a way that no one has explained and no one ever will." Costello also takes issue with what she calls the "ecological vision" harbored by most environmental scientists, which values biological diversity and the overall health of an ecosystem above the individual animal. This is not a point of view shared by individual animals, all of whom will fight for their individual survival, she argues. "Every living creature fights for its own, individual life, refuses, by fighting, to accede to the idea that the salmon or the gnat is of a lower order of importance than the idea of the salmon or the idea of the gnat," Costello explains.[14]

The third organized event of Costello's visit is a debate of sorts with Appleton philosophy professor Thomas O'Hearne. O'Hearne begins the debate by proposing that the animal rights movement is a specifically "Western crusade" which arose in nineteenth-century Britain. Non-western cultures can, with justice, argue that their cultural and moral values are different and do not require them to observe the same respect for animals mandated by Western animals rights activists. To this assertion, Costello responds that "kindness to animals ... has been more widespread than you imply." As an example of kindness to animals, she offers the keeping of pets, which is universal. And she notes that children enjoy a particular closeness to animals: "they have to be taught it is all right to kill and eat them."[15] Costello also proposes that industries that have been enacting animal cruelty for profit should have the greater role in atoning for that cruelty.[16]

O'Hearne next puts forward the argument that animals do not perform abstract reasoning, as demonstrated by the failure of apes to acquire more than a basic level of language, and are therefore not entitled to the same rights as humans. In response, Costello more or less restates her skepticism about the value of animal experiments. She refers to such experiments as "profoundly anthropocentric" and "imbecile." O'Hearne then proposes that animals do not understand death with the full consciousness of self with which humans regard death; therefore, to kill an animal quickly and painlessly is ethical.[17] O'Hearne's final point is that people cannot be friends with animals because we do not understand them. As an example, he uses the bat. "You can be friends neither with a Martian nor with a bat, for the simple reason that you have too little in common with them."[18] In her response, Costello equates the belief that animals are not entitled to equal rights because they do not reason abstractly, with racism. She then, once again, rejects reason as a valid basis for the animal rights argument, concluding that, if reason is all she shares with her philosophical opponents, then she has no use for it.[19]

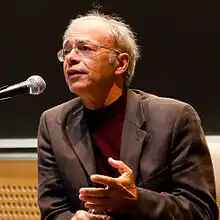

Peter Singer

In responding to Coetzee's novella, the philosopher Peter Singer, author of Animal Liberation (1975), writes a somewhat mocking short story featuring himself as "Peter" in a conversation with his daughter Naomi over the breakfast table. The fictionalized Peter complains to Naomi that Coetzee hasn't really delivered a lecture on animals rights. Instead, Coetzee has, Peter asserts, hidden behind the veil of fiction and the alter ego of Elizabeth Costello and so has not fully committed himself to any particular animal rights platform.[20]

Singer uses his imagined narrative to take issue with Costello's equation of a human life with a bat life. The human life is clearly more important, Peter argues, because the human invests so fully in the future and because of the human's superior intelligence and what he can accomplish. Peter also says that Costello provides no valid argument against the painless killing of animals, especially those of lower intelligence, like chickens and fish "who can feel pain but don't have any self-awareness or capacity for thinking about the future."[21]

Peter's most adamant complaint is the character's belief that she can "think [her] way into the existence of any being" using the same imaginative powers that she uses to create fictional characters.[22] Naomi more or less ridicules that idea, claiming that it is relatively easy to imagine a fictional character, and that doing so has no real application to understanding animals. "If that's the best argument Coetzee can put up for his radical egalitarianism, you won't have any trouble showing how weak it is," Naomi concludes. She goes on to suggest that Peter use the same fictional narrative device to respond to the Costello lecture. "Me? When have I ever written fiction?" Peter asks, concluding the reflection.[20]

Marjorie Garber, Wendy Doniger

Marjorie Garber reflects on how Coetzee's novella relates to her study of academic disciplines. Wendy Doniger takes as her starting point O'Hearne's contention that compassion for animals is a Western invention originating in the nineteenth century. She talks about the Hindu prohibition on harming animals and argues that compassion for animals can be found in many non-Western cultures throughout history.

Barbara Smutz

Anthropologist and University of Michigan professor Barbara Smuts takes as her starting point the near absence of any loving relationships between people and animals in Coetzee's novella. Smuts starts her reflection noting that, as a lonely old woman, Costello is likely to live with cats. But Costello never mentions any personal relationship with animals.[23] As a scientist, Smuts, at one point in her work, followed a group of baboons with whom she effectively lived as an equal. What she found was that she learned a great deal from the specialized knowledge of the animals. Specifically, they taught her how to find her way through the jungle without running amok of "poisonous snakes, irascible buffalo, aggressive bees, and leg-breaking pig-holes."[24]

She found that, in general, apes lead rich social and even emotional lives. As an example, she tells the story of visiting gorilla scientist Dian Fossey, and being hugged by a teenage gorilla. When she returned to civilization, Smuts adopted a rescue dog whom she named Safi. As an experiment, Smuts refrained from any traditional training of her animals, preferring to talk to her dog and make accommodations. She allows her dog the free use of its own toys, and her dog guards her when she takes a nap in the woods. In this way, Smuts tactfully builds on Costello's assertion that animals might be capable of more than we have traditionally assumed: "treating members of other species as persons, as beings with potential far beyond our normal expectations, will bring out the best in them, and ... each animal's best includes unforeseeable gifts."[25] Smuts' gentle contention is that people can learn more about animals from entering into real, personal relationships with them than from poeticizing or philosophizing about them.

Genre

The Lives of Animals straddles the boundary between essay and fiction. Bernard Morris, writing in the Harvard Review, called it "part fiction, part philosophical discourse, wholly human and absorbing."[2] Though the novella centers on the character Elizabeth Costello, much of the narrative is taken up with her lectures about cruelty to animals. Also making the book difficult to classify is its mixture of fiction, science and essay writing. While the contributions of Coetzee and Singer could be called short stories, Garber's contribution would more properly be called a scholarly article and Smuts' article, while grounded in her scientific studies, is mostly autobiographical and anecdotal.

See also

References

- J. M. Coetzee, The Lives of Animals, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999.

- Bernard E. Morris, Review of The Lives of Animals by J. M. Coetzee, Harvard Review, 18, Spring 2000, pp. 181–183.

- J. M. Coetzee, "The Lives of Animals" Archived 2011-09-25 at the Wayback Machine, The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Princeton University, 15 and 16 October 1997.

- Harold Fromm, "Review: Coetzee's Postmodern Animals", The Hudson Review, 52(2), Summer 2000 (pp. 336–344), p. 339.

- David Lodge, "Disturbing the Peace", The New York Review of Books, 20 November 2003.

- Andy Lamey, "Sympathy and Scapegoating," in Anton Leist, Peter Singer (eds.), J. M. Coetzee and Ethics: Philosophical Perspectives on Literature, Columbia University Press, 2013 (pp. 171–196), pp. 172–173, 179, 182.

- Coetzee 1997 Archived 2011-09-25 at the Wayback Machine, p. 133; Coetzee 1999, pp. 34–35.

- John Rees Moore, "Review: Coetzee and the Precarious Lives of People and Animals", The Sewanee Review, 109(3), Summer 2001 (pp. 462–474), p. 470.

- Coetzee 1999, pp. 15-69.

- Coetzee 1999, pp. 16, 36-37, 38.

- Coetzee 1999, p. 25.

- Coetzee 1999, pp. 28–29.

- Moore 2001, p. 471.

- Coetzee 1999, pp. 53-54.

- Coetzee 1999, p. 61.

- Coetzee 1999, pp. 60-61.

- Coetzee 1999, pp. 62-64.

- Coetzee 1999, p. 65.

- Coetzee 1999, p. 67.

- Coetzee 1999, p. 91.

- Coetzee 1999, pp. 89-90.

- Coetzee 1999, p. 90.

- Coetzee, 1999, pp. 107-108.

- Coetzee 1999, p. 109.

- Coetzee 1999, p. 120.

Further reading

- James Meek, “All About John", The Guardian, 5 September 2009.