Recurrent corneal erosion

Recurrent corneal erosion is a disorder of the eyes characterized by the failure of the cornea's outermost layer of epithelial cells to attach to the underlying basement membrane (Bowman's layer). The condition is excruciatingly painful because the loss of these cells results in the exposure of sensitive corneal nerves. This condition can often leave patients with temporary blindness due to extreme light sensitivity (photophobia).

| Recurrent corneal erosion | |

|---|---|

| |

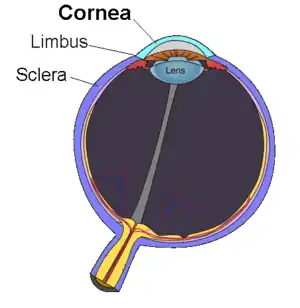

| Anatomy (normal) cornea | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms include recurring attacks of severe acute ocular pain, foreign-body sensation, photophobia (i.e. sensitivity to bright lights), and tearing often at the time of awakening or during sleep when the eyelids are rubbed or opened. Signs of the condition include corneal abrasion or localized roughening of the corneal epithelium, sometimes with map-like lines, epithelial dots or microcysts, or fingerprint patterns. An epithelial defect may be present, usually in the inferior interpalpebral zone.

Cause

Most cases of recurrent corneal erosion are acquired. There is often a history of recent corneal injury (corneal abrasion or ulcer), but also may be due to corneal dystrophy or corneal disease. In other words, one may develop corneal erosions as a result of another disorder, such as map-dot fingerprint dystrophy.[1] Familial corneal erosions occur in dominantly inherited recurrent corneal erosion dystrophy (ERED) in which COL17A1 gene is mutated.[2][3][4]

Diagnosis

The erosion may be seen by an eye doctor using the magnification of a biomicroscope or slit lamp. Usually fluorescein stain must be applied first and a cobalt blue-light used, but may not be necessary if the area of the epithelial defect is large. Optometrists and ophthalmologists have access to the slit lamp microscopes that allow for this more-thorough evaluation under the higher magnification. Mis-diagnosis of a scratched cornea is fairly common, especially in younger patients.

Prevention

Given that episodes tend to occur on awakening and managed by use of good 'wetting agents', approaches to be taken to help prevent episodes include:

- Environmental

- ensuring that the air is humidified rather than dry, not overheated and without excessive airflow over the face. Also avoiding irritants such as cigarette smoke.[5]

- use of protective glasses especially when gardening or playing with children.[5]

- General personal measures

- maintaining general hydration levels with adequate fluid intake.[5]

- not sleeping-in late as the cornea tends to dry out the longer the eyelids are closed.[5]

- Pre-bed routine

- routine use of long-lasting eye ointments applied before going to bed.[5]

- occasional use of the anti-inflammatory eyedrop FML (prescribed by an ophthalmologist or optometrist) before going to bed if the affected eye feels inflamed, dry or gritty

- use of a hyperosmotic (hypertonic) ointment before bed reduces the amount of water in the epithelium, strengthening its structure

- use the pressure patch as mentioned above.

- use surgical tape to keep the eye closed (if Nocturnal Lagophthalmos is a factor)

- Waking options

- learn to wake with eyes closed and still and keeping artificial tear drops within reach so that they may be squirted under the inner corner of the eyelids if the eyes feel uncomfortable upon waking.[5]

- It has also been suggested that the eyelids should be rubbed gently, or pulled slowly open with your fingers, before trying to open them, or keeping the affected eye closed while "looking" left and right to help spread lubricating tears. If the patient's eyelids feel stuck to the cornea on waking and no intense pain is present, use a fingertip to press firmly on the eyelid to push the eye's natural lubricants onto the affected area. This procedure frees the eyelid from the cornea and prevents tearing of the cornea.[5]

Treatment

With the eye generally profusely watering, the type of tears being produced have little adhesive property. Water or saline eye drops tend therefore to be ineffective. Rather a 'better quality' of tear is required with higher 'wetting ability' (i.e. greater amount of glycoproteins) and so artificial tears (e.g. viscotears) are applied frequently.

Nocturnal Lagophthalmos (where the eyelids do not close enough to cover the eye completely during sleep) may be an exacerbating factor, in which case using surgical tape to keep the eye closed at night can help.

Whilst individual episodes may settle within a few hours or days, additional episodes (as the name suggests) will recur at intervals.

Where episodes frequently occur, or there is an underlying disorder, one medical,[6] or three types of surgical curative procedures may be attempted:[7] use of therapeutic contact lens, controlled puncturing of the surface layer of the eye (Anterior Stromal Puncture) and laser phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK). These all essentially try to allow the surface epithelium to reestablish with normal binding to the underlying basement membrane, the method chosen depends upon the location and size of the erosion.

Surgical

A punctal plug may be inserted into the tear duct by an optometrist or ophthalmologist, decreasing the removal of natural tears from the affected eye.[8]

The use of contact lenses may help prevent the abrasion during blinking lifting off the surface layer and uses thin lenses that are gas permeable to minimise reduced oxygenation. However they need to be used for between 8–26 weeks and such persistent use both incurs frequent follow-up visits and may increase the risk of infections.[5]

Alternatively, under local anaesthetic, the corneal layer may be gently removed with a fine needle, cauterised (heat or laser) or 'spot welding' attempted (again with lasers). The procedures are not guaranteed to work, and in a minority may exacerbate the problem.

Anterior Stromal Puncture with a 20-25 gauge needle is an effective and simple treatment.

An option for minimally invasive and long-term effective therapy[9] is laser phototherapeutic keratectomy. Laser PTK involves the surgical laser treatment of the cornea to selectively ablate cells on the surface layer of the cornea. It is thought that the natural regrowth of cells in the following days are better able to attach to the basement membrane to prevent recurrence of the condition. Laser PTK has been found to be most effective after epithelial debridement for the partial ablation of Bowman's lamella,[10] which performed prior to PTK in the surgical procedure. This is meant to smoothen out the corneal area that the laser PTK will then treat. In some cases, small-spot PTK,[11] which only treats certain areas of the cornea may also be an acceptable alternative.

Amniotic membrane tissue corneal bandages such as Prokera have been shown to be effective in alleviating RCE.[12] These bandages aid in ocular surface regeneration while simultaneously protecting the cornea from further irritation.

Medical

People with recalcitrant recurrent corneal erosions often show increased levels of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) enzymes.[13] These enzymes dissolve the basement membrane and fibrils of the hemidesmosomes, which can lead to the separation of the epithelial layer. Treatment with oral tetracycline antibiotics (such as doxycycline or oxytetracycline) together with a topical corticosteroid (such as prednisolone), reduce MMP activity and may rapidly resolve and prevent further episodes in cases unresponsive to conventional therapies.[14][15] Some have now proposed this as the first line therapy after lubricants have failed.[6]

There is a lack of good quality evidence to guide treatment choices. A recently updated Cochrane Review[16] concluded that "Studies included in this review have been of insufficient size and quality to provide firm evidence to inform the development of management guidelines."

See also

Footnotes

- Review of Ophthalmology, Friedman NJ, Kaiser PK, Trattler WB, Elsevier Saunders, 2005, p. 221

- Jonsson F, Byström B, Davidson AE, Backman LJ, Kellgren TG, Tuft SJ, Koskela T, Rydén P, Sandgren O, Danielson P, Hardcastle AJ, Golovleva I (April 2015). "Mutations in collagen, type XVII, alpha 1 (COL17A1) cause epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophy (ERED)". Hum. Mutat. 36 (4): 463–73. doi:10.1002/humu.22764. PMID 25676728. S2CID 13562400.

- Oliver VF, van Bysterveldt KA, Cadzow M, Steger B, Romano V, Markie D, Hewitt AW, Mackey DA, Willoughby CE, Sherwin T, Crosier PS, McGhee CN, Vincent AL (April 2016). "A COL17A1 Splice-Altering Mutation Is Prevalent in Inherited Recurrent Corneal Erosions" (PDF). Ophthalmology. 123 (4): 709–22. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.12.008. PMID 26786512.

- Lin BR, Le DJ, Chen Y, Wang Q, Chung DD, Frausto RF, Croasdale C, Yee RW, Hejtmancik FJ, Aldave AJ (2016). "Whole Exome Sequencing and Segregation Analysis Confirms That a Mutation in COL17A1 Is the Cause of Epithelial Recurrent Erosion Dystrophy in a Large Dominant Pedigree Previously Mapped to Chromosome 10q23-q24". PLOS ONE. 11 (6): e0157418. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157418L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157418. PMC 4911149. PMID 27309958.

- Verma A, Ehrenhaus M (August 25, 2005) Corneal Erosion, Recurrent at eMedicine

- Wang L, Tsang H, Coroneo M (2008). "Treatment of recurrent corneal erosion syndrome using the combination of oral doxycycline and topical corticosteroid". Clin. Experiment. Ophthalmol. 36 (1): 8–12. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2007.01648.x. PMID 18290949. S2CID 205492163.

- Liu C, Buckley R (January 1996). "The role of the therapeutic contact lens in the management of recurrent corneal erosions: a review of treatment strategies". CLAO J. 22 (1): 79–82. PMID 8835075.

- Tai MC, Cosar CB, Cohen EJ, Rapuano CJ, Laibson PR (March 2002). "The clinical efficacy of silicone punctal plug therapy". Cornea. 21 (2): 135–9. doi:10.1097/00003226-200203000-00001. PMID 11862081. S2CID 25764419.

- Baryla J, Pan YI, Hodge WG (2006). "Long-term efficacy of phototherapeutic keratectomy on recurrent corneal erosion syndrome". Cornea. 25 (10): 1150–1152. doi:10.1097/01.ico.0000240093.65637.90. PMID 17172888. S2CID 8701971.

- Kampik D, Neumaier K, Mutsch A, Waller W, Geerling G (2008). "Intraepithelial phototherapeutic keratectomy and alcohol delamination for recurrent corneal erosions--two minimally invasive surgical alternatives". Klinische Monatsblätter für Augenheilkunde. 225 (4): 276–80. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1027174. PMID 18401793.

- van Westenbrugge JA (2007). "Small spot phototherapeutic keratectomy for recurrent corneal erosion". J Refract Surg. 23 (7): 721–4. doi:10.3928/1081-597X-20070901-13. PMID 17912944.

- Huang, Yukan; Kheirkhah, Ahmad; Tseng, Scheffer C. G. (26 March 2012). "Placement of ProKera for Recurrent Corneal Erosion". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 53 (14): 3569.

- Ramamurthi S, Rahman M, Dutton G, Ramaesh K (2006). "Pathogenesis, clinical features and management of recurrent corneal erosions". Eye. 20 (6): 635–44. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6702005. PMID 16021185.

- Hope-Ross M, Chell P, Kervick G, McDonnell P, Jones H (1994). "Oral tetracycline in the treatment of recurrent corneal erosions". Eye. 8 (Pt 4): 384–8. doi:10.1038/eye.1994.91. PMID 7821456.

- Dursun D, Kim M, Solomon A, Pflugfelder S (2001). "Treatment of recalcitrant recurrent corneal erosions with inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase-9, doxycycline and corticosteroids". Am J Ophthalmol. 132 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(01)00913-8. PMID 11438047.

- Watson SL, Leung V (2018). "Interventions for recurrent corneal erosion". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (7): CD001861. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001861.pub4. PMC 6513638. PMID 29985545.

External links

- Facts About the Cornea and Corneal Disease The National Eye Institute (NEI)