Costabile Farace

Costabile "Gus" Farace, Jr.[1] (June 21, 1960 Bushwick, Brooklyn – November 17, 1989 Bensonhurst, Brooklyn) was an Italian American criminal and mobster. He was an associate of the Bonanno crime family who murdered a teenage male prostitute and a federal Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agent in New York City. He was shot and killed by an unknown assailant in 1989.

Costabile Farace | |

|---|---|

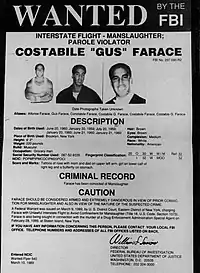

FBI Wanted Poster of Costabile Farace issued on March 10, 1989 | |

| Born | Costabile "Gus" Farace, Jr. June 21, 1960 |

| Died | November 17, 1989 (aged 29) |

| Cause of death | Shot to death |

| Nationality | Italian American |

| Other names | Nicholas |

| Height | 6 ft 3 in (191 cm) |

| Parents |

|

Biography

Early years

Farace was born on June 21, 1960, in Bushwick, to Mary and Costabile "Gus" Farace, Sr., a first-generation immigrant from Camastra, Agrigento province Sicily. At the age of five he moved with his family from Bushwick to Tottenville, Staten Island. He sometimes used the name "Nicholas" as an alias while a fugitive and gave several alternate dates of birth: August 20, 1959, January 1, 1960, and June 20, 1960. He stood at 6'3", weighed 220 pounds, and sported a tattoo of a girl on his lower calf, another girl tattoo on his right leg, and a butterfly on his stomach. Later that year, Farace's family moved to Prince's Bay, Staten Island.

His father Gus opened a small grocery store, G&S, in the island's Great Kills neighborhood on Hylan Boulevard. The store closed in 1983.

Costabile, Sr. and his brother Frank were fringe members of a Colombo crime family illegal gambling ring. Farace was a paternal first cousin of Dominick Farace, the son of Frank Farace. He also was a cousin to Michael A. Farace, Michael J. Farace, and Vincent Farace. Vincent Farace is a recognized made man in the Bronx faction of the Bonanno crime family.

Costabile attended Totten Intermediate School 34 in Tottenville (the former site of Tottenville High School until it moved to its present location in 1972), where he was considered the class flirt in eighth grade. As a child he was considered the class clown, a poor student, popular, and gregarious. He played Peewee football in Wolfe's Pond Park. In 1975, he entered Tottenville High School and joined a street gang of adolescent delinquents called "the Bay Boys", named after the Upper New York Bay near Tottenville. The gang liked to intimidate people and start fights. In January 1977, he was pulled over for reckless driving and, after searching him, the police found a gun on his person. Three weeks later, he was arrested for forgery, but he avoided a jail sentence because he was a youth. He listed his occupation as a grocer.

Assaults and Killing in Greenwich Village

On October 7, 1979, Farace murdered a 17-year-old boy and brutally beat the victim's 16-year-old companion. Farace and three friends were on a street in the Greenwich Village section of Manhattan when the two boys allegedly propositioned them. Enraged, Farace and his accomplices — later identified , David Spoto, and Robert DeLicio — forced the two teenagers into the Farace group's car and drove them to the beach at Wolfe's Pond Park in Prince's Bay, Staten Island. Once there, the men beat the boys using driftwood and other objects, then left them for dead. The 17-year-old, Steven Charles of Newark, New Jersey, died on the beach. The 16-year-old, Thomas Moore of Brooklyn, was critically injured, but dove into the pond and managed to elude his attackers. Moore then walked to a nearby residence for assistance. Later on October 8, the police arrested Farace, DeLicio, and Spoto. Four days later, Moore identified Farace and the other suspects from a police lineup.[2]

On December 10, 1979, Farace pleaded guilty to first-degree manslaughter. The state had accepted his manslaughter plea rather than go through the uncertainty and expense of a trial, and of even winning a conviction in virulently anti-gay Staten Island (they particularly feared that Farace and his co-defendants would use the "gay panic defense"). Farace was sentenced to 7 to 21 years in prison.[3]

Relationship with organized crime

It was in prison that Farace first met Gerrard "Jerry" Chilli, Sr. As Robert Stutman writes in Dead on Delivery: "Blamed for some infraction of the inmate’s code, Petrucelli was about to be killed with a set of barbells in a weight room brawl when Farace interceded, saving his life."[4] Chilli unofficially "adopted" Farace, who at that point was in his late twenties, as a protégé, and stayed in contact when Chilli got out of prison. Farace used his contacts with old friends, and new ones he met in prison, to start a marijuana selling business, which soon expanded into other drugs. In June 1988, Farace was released from prison.[5] By June 3, 1988, Farace had become partners with his friend Gregory Scarpa, Jr. who worked out of his criminal headquarters at Wimpy Boys Athletic Club. Scarpa's father, Gregory Scarpa, Sr., was a secret FBI informer. Farace married Antoinette Acierno, a sister of a criminal associate.[2]

Murder of DEA Agent Hatcher

After being released on parole on June 3, 1988, Farace soon got into trouble again. He began selling small amounts of cocaine and marijuana, and in late February 1989, set up a cocaine deal with Everett Hatcher, an undercover federal Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agent. At approximately 10:00 p.m. on the evening of February 28, 1989, Farace was to meet Hatcher at a remote overpass on the West Shore Expressway in the Rossville section of Staten Island to complete the deal. Hatcher had met Farace to discuss purchasing cocaine from him on several occasions.[6] During the course of the drug transaction, Hatcher got separated from the surveillance team. When the team finally found Hatcher, he had been shot through the head three times in his unmarked Buick Regal. The window was rolled down and the Regal's engine was on, but Hatcher's foot was on the brake.

Police theorized that Farace shot Hatcher from a van as it passed Hatcher's car. The van was found abandoned three days later on a street about two miles northeast of the murder scene. This location was less than half a mile from the Arthur Kill Correctional Facility, where Farace had spent the last two years of his manslaughter sentence. It is not known why Farace killed Hatcher; one theory is that Farace had become suspicious of Hatcher from rumors he had heard.[2]

Manhunt

Hatcher's death was the first murder of a DEA agent in New York City since 1972. He was also believed to have been the first law enforcement officer killed in the line of duty on Staten Island.

After Hatcher's slaying, a nationwide manhunt for Farace commenced. The Federal Bureau of Investigation placed Farace on the Ten Most Wanted list. Local and federal law enforcement increased their surveillance of Cosa Nostra members, stopping them to take photographs and ask questions. As pressure increased on the Bonanno family, its leadership decided to kill Farace.

Following the Hatcher murder, Gregory Scarpa, Sr. told David Krajcek of the Daily News that the Farace and Scarpa families were no longer close. No one from the Scarpa family had gone to Farace's wedding to Toni Acierno a few months earlier. Scarpa feared that a strong connection would send his convicted drug dealer son, Gregory Jr., to a distant federal prison.

Meanwhile, Farace was hiding with friends and criminal associates around the Greater New York area. He first stayed with Margaret "Babe" Scarpa, an old girlfriend who was Chilli's daughter. Soon after Farace had departed, the police raided Scarpa's house and arrested her; at the scene, DEA official Stutman told Chilli he could blame Farace. At this point, an aggravated Chilli wanted Farace killed. A new mob associate with the Lucchese family, John Petrucelli, was helping Farace find places to hide. Chilli met with Petrucelli and Lucchese capo Mike Salerno to discuss the situation. Chilli demanded that Petrucelli kill Farace, but Petrucelli refused. Two months later, Petrucelli was found dead with a hood over his head, which is a Sicilian message for "never keep secrets from the family".[7]

Shooting and death

Less than ten months after the Hatcher murder, the manhunt for Farace would be over. At 11:08 p.m. on November 17, 1989, police dispatchers received a 9-1-1 emergency call about a car parked at 1814 81st Street in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn. The car contained one male occupant, with another male lying face down on the sidewalk, both of whom had just been shot. (The call came in as "shots fired", no other specifics.)

Police rushed to the scene and found the two men, one dead and the other seriously wounded. The dead man was identified as Costabile Farace. He had gunshot wounds to the head, neck, back and leg. According to witnesses, a van had driven alongside Farace's car and shot the two men nine times. This was the same method Farace had used to kill Agent Hatcher. The survivor in the car was identified as Joseph Sclafani, a member of Farace's organization. Sclafani said he fired two shots at the assailants.[8]

In a different version of this story, per the responding officer, Farace was still breathing when police arrived. They placed him in a trauma suite, but he died en route to the hospital. Sclafani was outside of the vehicle, having been shot out of his shoes. Officers handcuffed him on the scene for weapons possession.

Aftermath

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York refused to grant Farace a public funeral mass, citing his notorious life and death. However, the Archdiocese did permit his remains to be buried in the church-owned Cemetery of the Resurrection in Pleasant Plains, Staten Island, the same area where Hatcher was murdered.

On September 17, 1997, Lucchese family soldier James Galione and Lucchese family associate Mario Gallo admitted in court to murdering Farace.[9] A third mobster, Louis Tuzzio, who was slain in 1990, was the third member of their team.[10][11] Daniel "Dirty Danny" Mongelli was convicted of killing Tuzzio in 2004 and was released from prison in 2020 after catching COVID-19.[11]

A made-for-TV movie, Dead or Alive: The Race for Gus Farace (1991) starred Tony Danza as Farace.[12] The movie alleged that the mob was trying to kill Farace before the FBI could apprehend him.[13] The movie Out For Justice starring Steven Seagal was based on Gus Farace's manhunt.

References

- "426. Costabile "Gus" Farace". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on 2019-10-10. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- Pooley, Eric (January 29, 1990). "Death of a Hood". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- "The 'Perplexing' Killing of a Drug Agent". The New York Times. March 2, 1989. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- "Mob Report: Alphonse "Little Al" D'Arco – Revisited (Part 2)". Rick Porello's AmericanMafia.com. November 11, 2002. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- "Informant reportedly comes forward in drug agent's death". upi.com. May 26, 1989. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- "Everett E. Hatcher Drug Enforcement Administration website". Archived from the original on 2010-02-17. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- Pourelle, Rick (November 11, 2002). "Like Father, Like Son". Pourelle's American Mafia. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- French, Howard W. (November 19, 1989). "Suspect in Drug Agent's Slaying Found Shot to Death". New York Times. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- Rizzi, Albert (16 June 2019). "From 'Mob Cops' to 'Boobsie': Alleged Lucchese activity on Staten Island over the years". SI Live. News Paper. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- "In Plea Bargain, Two Admit Guilt in Mob Figure's '89 Killing" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine By JOSEPH P. FRIED New York Times September 18, 1997

- "Killer Bonnano [sic] mobster released from prison after catching COVID-19". www.msn.com. Retrieved 2020-12-09.

- Dead and Alive: The Race for Gus Farace, archived from the original on 2018-06-16, retrieved 2019-10-11

- "Dead and Alive: The Race for Gus Farace". IMDb. Archived from the original on 2018-06-16. Retrieved 2018-06-29.

Further reading

- "Death of a Hood: The bloody end of Big Bad Gus". New York (magazine), January 29, 1990.

- "Farace's Wife Is Held on Marijuana Charge". The New York Times. Associated Press. October 15, 1989.

- "Farace's Wife Free On $250,000 Bail". The New York Times. October 17, 1989.

- Raab, Selwyn (2005). Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-30094-8.

- Stutman, Robert M. Stutman; Esposito, Richard Esposito (May 1992). Dead on Delivery: Inside the Drug Wars, Straight from the Street. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-51558-0.

- "Suspect Still Hunted in Drug Agent Death". The New York Times. March 3, 1989.